“I never practice. From time to time, I just open my case and throw in a piece of raw meat.” A rare interview with the guitar ace who spurned the jazz world, climbed the pop charts and lived in terror of taking a solo

Wes Montgomery revealed the insecurities that forced his retreat from jazz, even as he was celebrated as a giant of jazz

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

“The first time I heard Wes Montgomery play, it was like being hit by a bolt of lightning. Once he hit the guitar strings with his thumb, you could feel it in your gut anywhere within the reach of sound.”

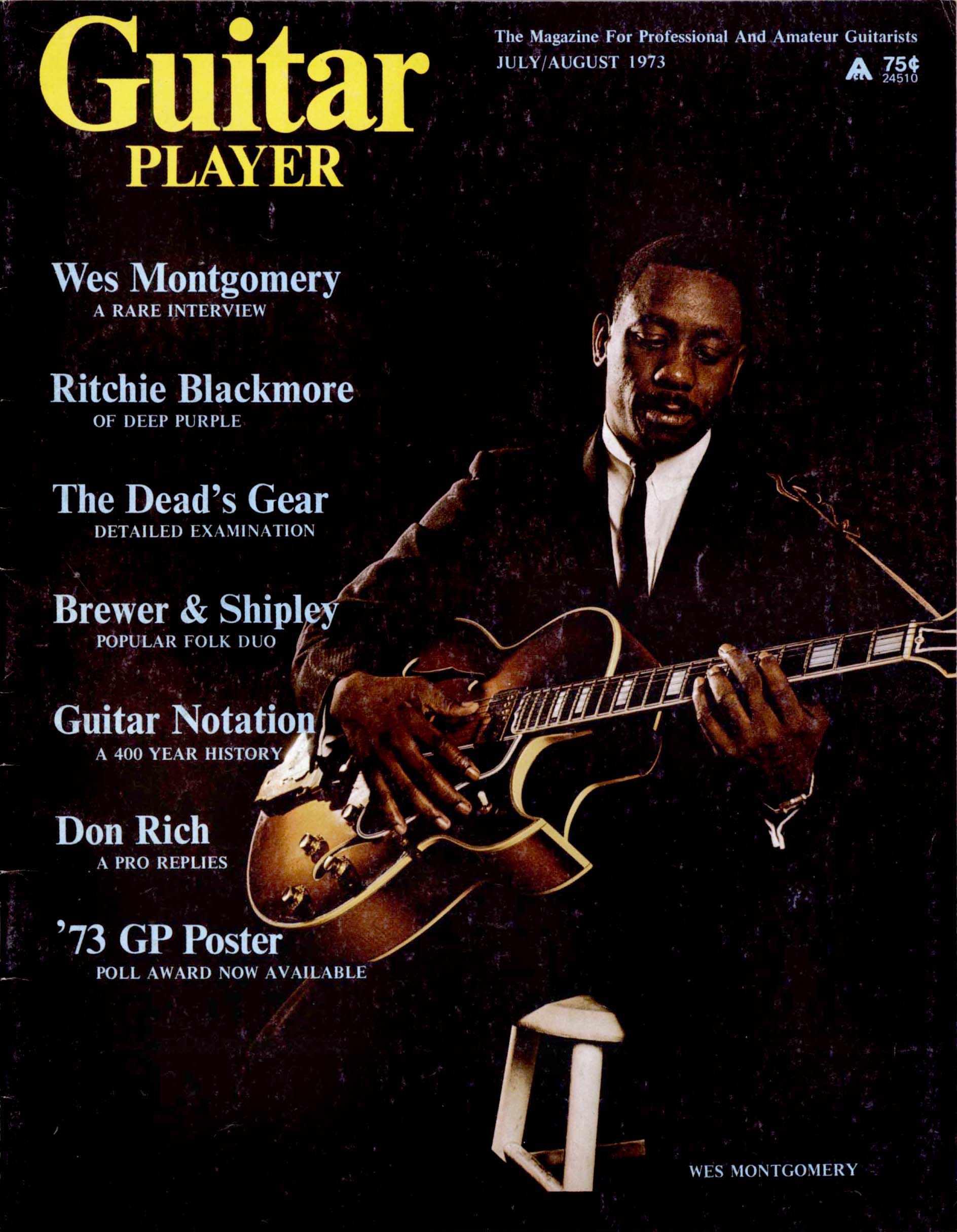

So recalled Ralph Gleason in a 1973 piece about the jazz guitarist for Guitar Player. Gleason had interviewed Montgomery many years earlier, but the interview went unpublished until it appeared in GP’s pages for a cover feature in the July/August issue.

By then Gleason was known as a co-founding editor of Rolling Stone magazine, and Montgomery, a giant of jazz guitar, was five years in the grave. As a longtime music critic and columnist based in San Francisco, Gleason knew Montgomery in his early years, when Wes and his brothers, Buddy and Monk, had a group in town called the Mastersounds. Wes released his first album as a leader, The Wes Montgomery Trio (a.k.a. A Dynamic New Sound), in 1959, which is around the time Gleason spoke with him.

Gleason’s interview is a candid portrait of Wes that reveals the doubts he harbored about his talent and the struggles he faced with his playing. He took up guitar relatively late, at age 19. Untrained on the instrument, he taught himself by listening to Charlie Christian records, all while raising seven kids and working as a welder. Even by the early 1960s, when his star was ascendant in the jazz world, he felt he lacked the talent of more experienced jazz guitarists who had years of playing behind them.

“Wes was actually very insecure about his own playing and very worried that when it came his tum to solo night after night, he wouldn’t be able to consistently maintain the standard he wanted,” Gleason wrote.

Invitations to perform with jazz giants did nothing to ease his mind. Montgomery once turned down an offer from John Coltrane. “It wasn’t just the money,” Gleason wrote, “it was the fact that he couldn’t think of himself as the leader in his field. He was always saying that he had played much better 15 years before.”

Montgomery was also troubled by his electric guitar sound. He favored the tone of Gibson jazz archtops, including the L-7, L-5 CES and ES-175, but had little success finding a combo that suited him. Part of the problem was his string gauges. He played a heavy, .014–.058 set, and was constantly looking for ways to brighten the sound. He tried Fender Super Reverbs and Twins before switching to a Standel Custom XV, according to Jazzguitar.be.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“He never got the sound he wanted out of any amplifier,” Gleason wrote, “and spent thousands of dollars hassling with electronics. I don’t believe that in his whole professional life he ever really got the kind of sound onstage that would have made him happy. The Fender people and everybody else must have been driven crazy.”

It takes years to start working with it, and it looks like everybody else is moving on the instrument but you.”

— Wes Montgomery

Montgomery gave few interviews in his life. In one quote that is frequently attributed to him, he stated, “I never practice guitar. From time to time, I just open my guitar case and throw in a piece of raw meat.”

It may be apocryphal, but it gets to the heart of his feeling about guitar: It was a beast that demanded blood. Montgomery seemed to live in constant fear of it.

“It’s a very hard instrument to accept, because it takes years to start working with it, that’s first,” he told Gleason, “and it looks like everybody else is moving on the instrument but you. Then, when you find a cat that’s really playing, you always find that he’s been playing a long time. You can’t get around it.”

If Montgomery had a signature, it was his talent for playing octaves. Starting out a solo with single notes, he’d build to octaves before moving on to block chords to create a dynamic structure that kept listeners’ ears pinned to his deft finger work.

His octave improvisations were sophisticated and lyrical. Players marveled at his mastery of such a difficult technique. But Wes, true to form, was modest about it to the point of being dismissive.

I used to have headaches every time I played octaves, because it was extra strain, but the minute I’d quit I’d be all right. It was my way, and my way just backfired on me.”

— Wes Montgomery

“I’m so limited. Like, playing octaves was just a coincidence,” he told Gleason. “And it’s still such a challenge, like chord inversions — block chords like cats play on piano. There are a lot of things that can be done with it, but each is a field of its own, and like I said, it takes so much time to develop all your technique.

“I used to have headaches every time I played octaves, because it was extra strain, but the minute I’d quit I’d be all right. I don’t know why, but it was my way, and my way just backfired on me.

“But now I don’t have headaches when I play octaves. I’m just showing you how a strain can capture a cat and almost choke him, but after a while it starts to ease up, because you get used to it.”

Montgomery’s decision to sound the strings with his thumb, rather than a pick, came about from his after-hours practice. Afraid to wake or disturb anyone, he brushed the side of his thumb down the strings to create a softer sound. Like his use of octaves, it would prove to be part of his distinctive style, but he saw it largely as a deficit.

“That’s one of my downfalls, too,” he said. “In order to get a certain amount of speed you should use a pick, I think. A lot of cats say you don’t have to play fast, but being able to play fast can cause you to phrase better.

“But I just didn’t like the sound. I tried it for about two months. Didn’t use the thumb at all. But after two months I still couldn’t use the pick, so I said I’d go ahead and use the thumb.

“But then I couldn’t use the thumb either, so I asked myself which are you going to use? I liked the tone better with the thumb, but the technique better with the pick, but I couldn’t have them both.”

Seemingly every direction he turned brought new threats. Classical guitarists, with their virtuosity and gravitas, were phantoms in the shadows of his thoughts. Asked if he’d ever run into any, Wes declared, “No, and I don’t want to, because these cats will scare you. It doesn’t make any difference that they’re playing classic, but there’s so much guitar.

“Like, if you hear a classical guitar player, he’ll make you feel like, ‘What’re you playing the thing you’re playing for? This is what you should be playing.’”

But it was soloing that he feared most. Gleason wondered if Montgomery would be happier playing rhythm like Freddie Green did for Count Basie.

“It would be all right,” the guitarist replied, “but

I don’t know that many chords. I’d be loaded if I knew that many. I’d probably go join a band and just play rhythm, man.”

— Wes Montgomery

“But that’s not my aim,” he continued. “My aim is to move from one vein to the other without any trouble.

“Like, if you’re going to take a melody line or a counterpoint or unison line with another instrument, do that, then maybe drop out at a certain point, then maybe next time you’ll play phrases and chords, or maybe you’ll take an octave or something. That way you’ll have a lot of variations there.”

Perhaps it was his insecurity among jazzers that made Montgomery reach for a new market. In the years after his interview with Gleason, he scored success after success with instrumental records that crossed over to the pop format. “California Dreamin’,” “Windy” and “A Day in the Life” brought him new listeners and fame, even as purists decried his musical direction. It was short-lived, though. Montgomery died of a heart attack on June 15, 1968, at his home in Indianapolis. He was 45 years old.

Christopher Scapelliti is editor-in-chief of GuitarPlayer.com and the former editor of Guitar Player, the world’s longest-running guitar magazine, founded in 1967. In his extensive career, he has authored in-depth interviews with such guitarists as Pete Townshend, Slash, Billy Corgan, Jack White, Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren, and audio professionals including Beatles engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott. He is the co-author of Guitar Aficionado: The Collections: The Most Famous, Rare, and Valuable Guitars in the World, a founding editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine, and a former editor with Guitar World, Guitar for the Practicing Musician and Maximum Guitar. Apart from guitars, he maintains a collection of more than 30 vintage analog synthesizers.

- Ralph GleasonContributing writer