“He’s such a d*** that he’ll probably never get the credit he deserves.” Billy Corgan on the paradox of being Ritchie Blackmore

Blackmore blamed his ruthlessness on insecurity — and the anxiety he couldn’t outrun

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

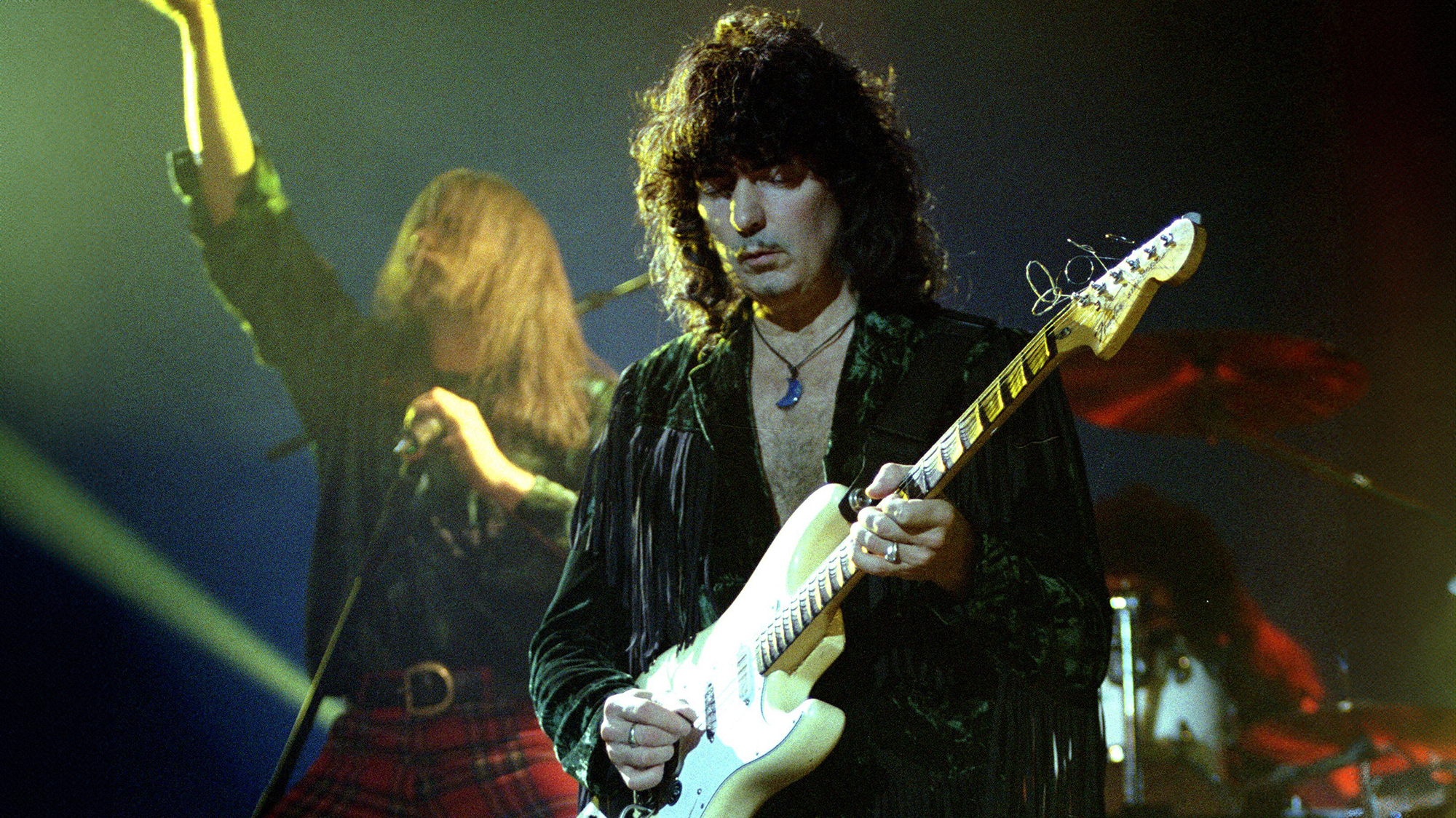

Ritchie Blackmore’s ruthlessness is the stuff of rock lore. After forcing out Ian Gillan and dismissing bass guitarist Roger Glover from Deep Purple, he blindsided the remaining members in 1975 by bolting to form Rainbow. One album into that venture, he fired everyone but singer Ronnie James Dio and continued to rotate musicians in and out as they failed to meet his unforgiving standards.

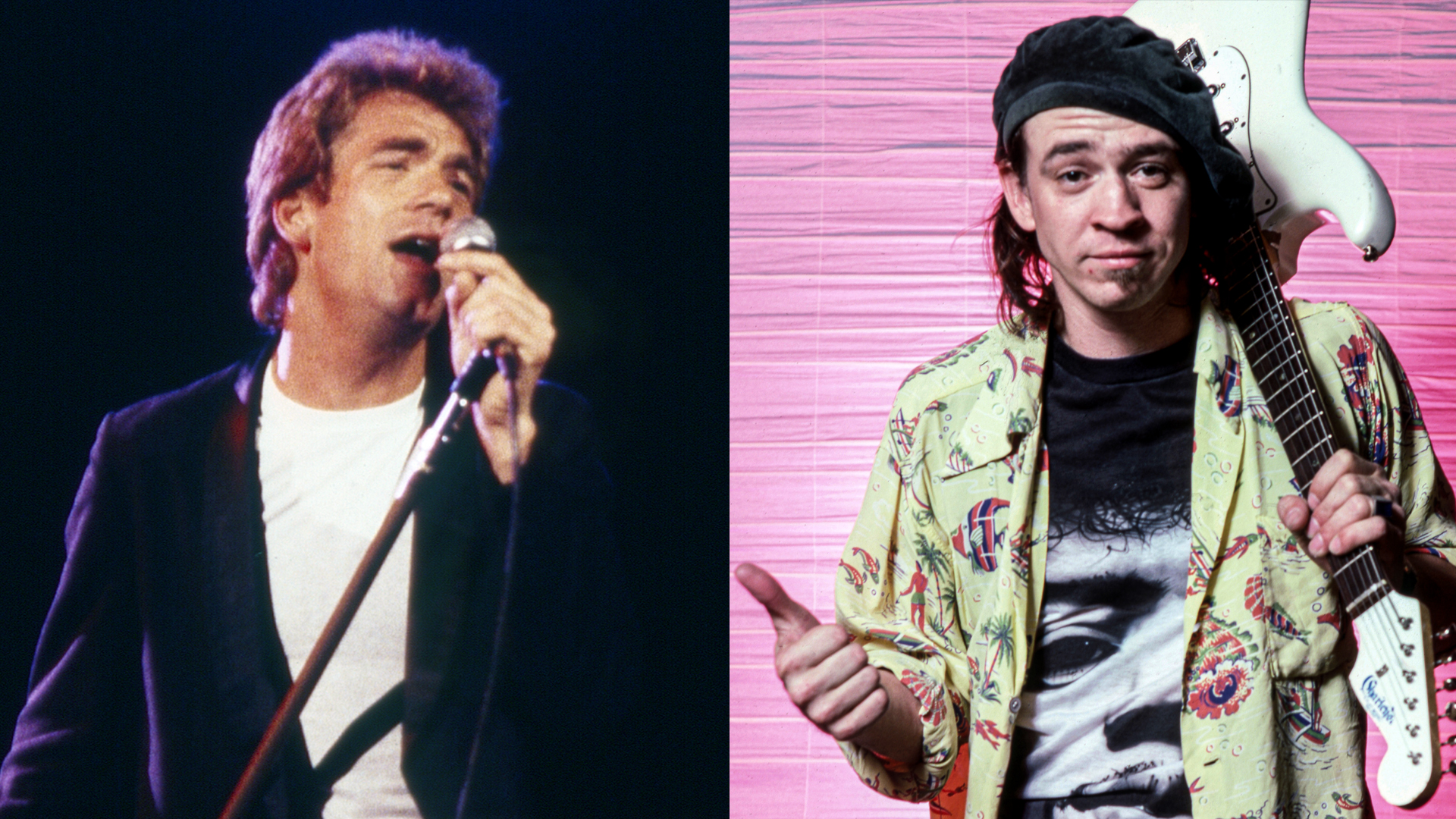

That relentless, almost surgical pursuit of perfection was felt far beyond his own ranks; it reverberated through the generation of electric guitar players raised on his records. As Billy Corgan of the Smashing Pumpkins told Guitar Player in 1995, “Pound for pound, he’s one of the best soloists in history, but he’s such a dick that he’ll probably never get the credit he deserves.”

No one understood the paradox better than Blackmore himself. Asked one year later about his reputation for being difficult, he didn’t deflect. He indicted the entire enterprise.

Article continues below

“I hate show biz. I hate people who confine themselves to the system,” he told Guitar Player. “Why does everyone have to do the right interview at the right time, be on the right program, be politically correct, say the right things and be at the right parties? That gets up my nose. Why can’t I just play the guitar? It’s all I want to do.”

He wanted to play guitar so badly that the social glue binding bands together often became collateral damage. An early encounter with Eric Clapton makes the point.

“He was the big thing in the area back in ’67,” Blackmore recalled. “He was God — it said so all through London, so I believed it.”

When he saw Clapton perform, however, he was unsettled by his patience.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“He played very slowly with vibrato, which no one I knew bothered with because they were too interested in playing as fast as they could,” Blackmore said. “My feeling was, if you play vibrato you’re wasting time. ‘C’mon, let’s get on to the next note and show off!’

“I said to him, ‘You play with all this vibrato. That’s very different.’

“That was very stupid to say in retrospect. Of course he plays with vibrato, and why not?

“But I felt that he was the strange person to put so much emphasis on the vibrato. It was very pleasurable to the ear, but I thought he could be playing other notes.”

Of course a wide, vocal-like vibrato would become one of Blackmore’s signatures, fused with the velocity — and inhuman stage volume and guitar thrashing — that defined his early style. In time, he recognized the lesson.

“That’s thanks to Eric Clapton in a way,” he admitted. “It’s only now that it dawns on me that the guy knew what he was playing way back then, and I was the idiot for saying, ‘Why are you playing with a vibrato? Why are you bothering?’ That’s embarrassing.

That’s thanks to Eric Clapton in a way. It’s only now that it dawns on me that the guy knew what he was playing way back then.”

— Ritchie Blackmore

“He was into Freddie King, but that didn’t do it for me then. Those guys were too slow for me. I wanted to hear something fast. Let’s go here!

“I was always so nervously charged that I had to be fast. I learned in reverse. I learned to be fast and now I’m trying to slow down and say something. Playing a fast solo, I suppose, is a bit like having two-second sex.”

If the bravado was bracing, the insecurity beneath it was even more revealing. Blackmore has long suggested that his difficulty with bandmates stemmed less from arrogance than from self-doubt.

“I’d love to play with another guitarist, although I’m still insecure, so that guitarist couldn’t be better than me,” he said. “I still go through life being very unsure of what I’m doing, and I cover that by appearing confident, as if I know exactly what I’m doing.

“But I have no idea. There’s a constant searching. Some days I tell myself I can play. And other days I think, ‘I’ve been playing for 38 years and I’m still floundering. Why am I so miserable with my guitar playing? I can’t seem to get it down!’ I’ll hear my solos and think, ‘Why did I accept that? I know damn well I can play better than that.’”

The studio, he conceded, is the most unforgiving environment of all.

“My best stuff is live, because I don’t have time to think; I just get on with it. But in the studio, I very rarely feel at ease. If someone points to me and says, ‘Play — we’re going to test you to see how good you are,’ I get self-conscious and disintegrate.

“I need a psychiatrist with me when I’m in the studio, going, ‘It’s all right, Ritchie. Nobody hates you, nobody’s testing you, nobody’s watching you.’”

I get self-conscious and disintegrate. I need a psychiatrist with me when I'm in the studio.”

— Ritchie Blackmore

He laughed at the absurdity — but only to a point.

“Sometimes I’ll talk to the producer: ‘Does the engineer play the guitar?’ ‘Yes, I think he does a bit.’ ‘How much? What is he into?’ Then I’ll have to sit behind the engineer, because I don’t want him looking at what I’m playing, because I’ll interpret that as him thinking I’m not playing very well. I took up the guitar because I felt insecure at school, and that insecurity is still there — that strange introversion.”

Christopher Scapelliti is editor-in-chief of GuitarPlayer.com and the former editor of Guitar Player, the world’s longest-running guitar magazine, founded in 1967. In his extensive career, he has authored in-depth interviews with such guitarists as Pete Townshend, Slash, Billy Corgan, Jack White, Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren, and audio professionals including Beatles engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott. He is the co-author of Guitar Aficionado: The Collections: The Most Famous, Rare, and Valuable Guitars in the World, a founding editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine, and a former editor with Guitar World, Guitar for the Practicing Musician and Maximum Guitar. Apart from guitars, he maintains a collection of more than 30 vintage analog synthesizers.