“I’d trade 150 Def Leppards for one R.E.M. It's as simple as that.” Pete Townshend on the music he despises, even though he influenced it with one vital Who album

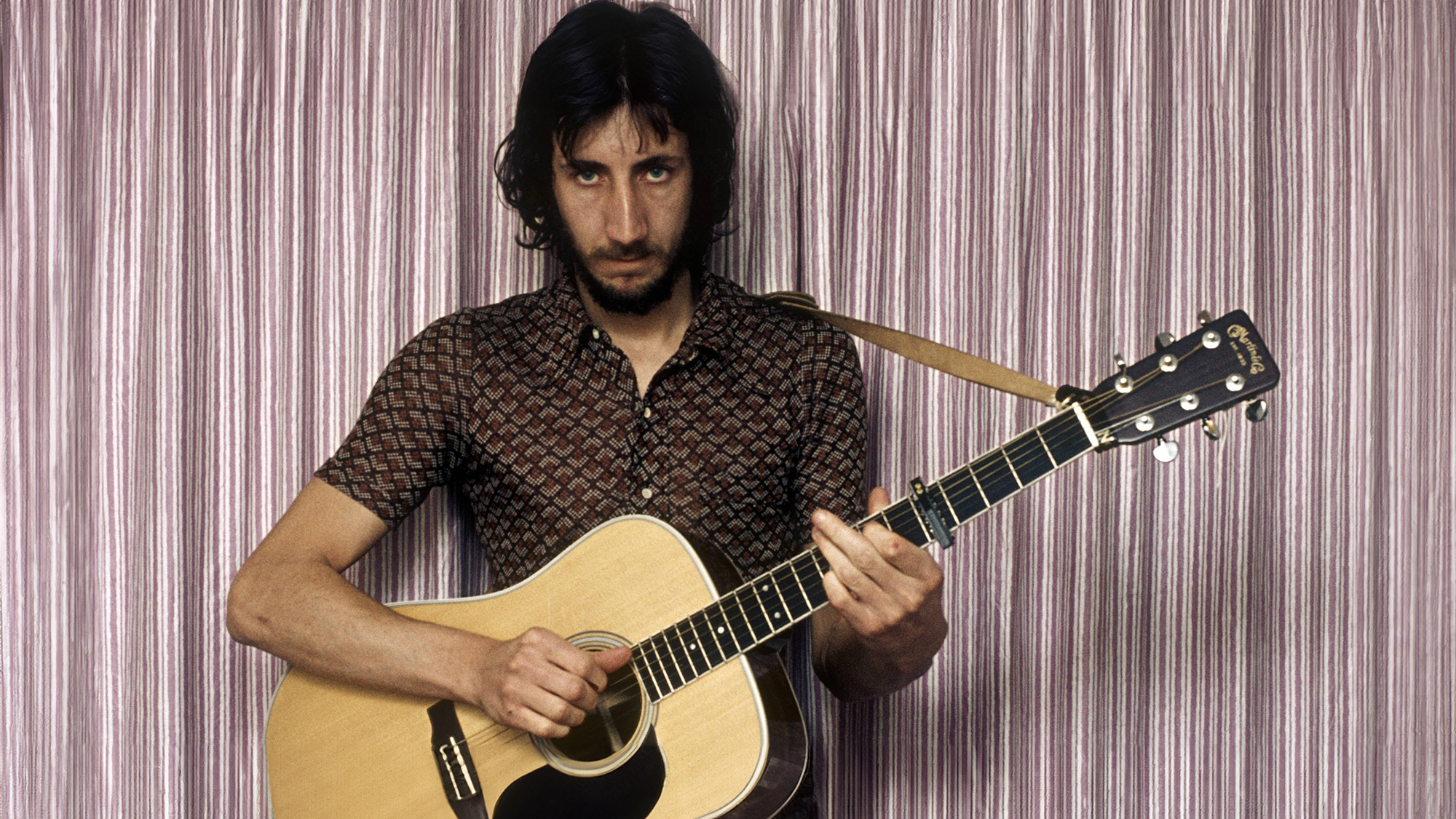

The guitarist wondered “why these guys look like that, and why it is that they think they look so cool?”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

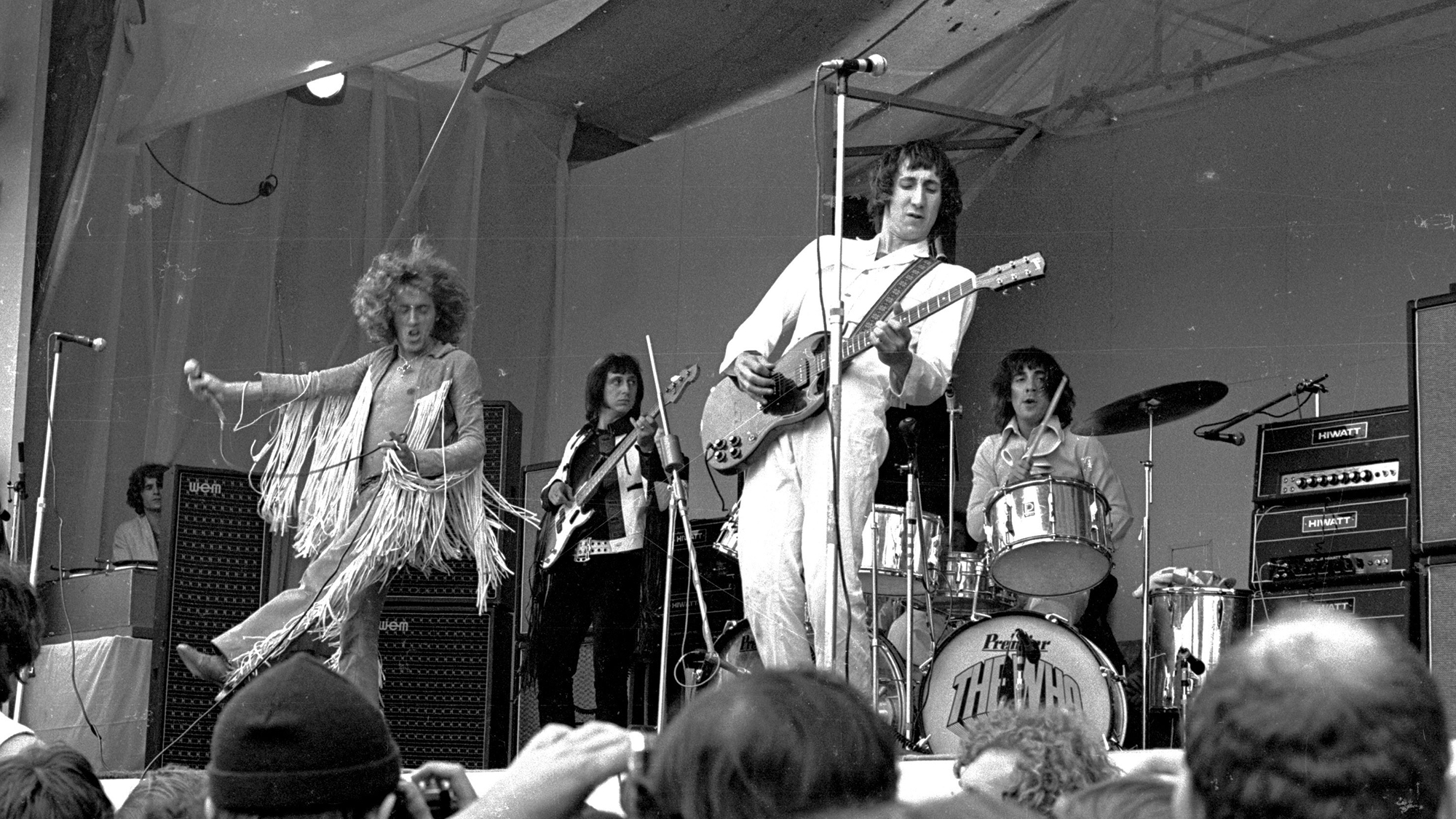

More than a decade before the first distorted power chords echoed through London’s underground punk clubs, Pete Townshend was drafting that genre’s blueprint. While his mid ’60s contemporaries were lost in psychedelic whimsy or blues-rock virtuosity, the Who’s primary architect was busy weaponizing the electric guitar and transforming the stage into a theater of destruction that prized raw, visceral energy over technical perfection.

Feedback and smashed Rickenbackers were the results of his frustration with both suburban life and his limited guitar skills. Townshend and the Who didn’t merely play music — they assaulted it with sheer volume and a ferocious approach the punks would follow.

Townshend was thrilled with punk and happy to be recognized as its godfather. He was, however, less enamored with another genre of music that bore his sonic signature: heavy metal.

Years before punk’s arrival, Townshend was being credited for laying the foundation of heavy metal with the Who’s live 1970 document, Live at Leeds. The record is considered among the greatest live albums in rock history, capturing the Who at their raucous peak as Townshend wielded distortion, feedback and power chords to create a sound that was heavier and more aggressive than anything previously recorded.

Live at Leeds tracks like “Young Man Blues,” “My Generation” and “Summertime Blues” established the high-gain and overwhelming intensity that would become the foundational requirement for all metal that followed. Even Eddie Van Halen studied the album, down to each of Townshend’s riffs and solos.

“We sort of invented heavy metal with Live at Leeds,” Townshend told the Toronto Sun in 2019. “We were copied by so many bands, principally by Led Zeppelin, you know, heavy drums, heavy bass, heavy lead guitar.”

But as Townshend revealed in a 1989 interview with Guitar Player, the genre transformed into something he scarcely recognized by the dawn of that decade. The glam trappings of spandex, makeup and big hair were ubiquitous, as were the “bad boy” lyrics of heavy-metal songs and the virtuoso solos played on pointy electric guitars.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“I think it's very lighthearted, isn't it?” Townshend offered in a 1989 interview with Guitar Player. “You know, I'm not into men in spandex trousers with hair like that [holds palm one foot from head]. I'm kind of confused as to why these guys look like that, and why it is that they think they look so cool. Maybe they would just say that I was old-fashioned, I don't know.”

He had to admit, though, that the guitar playing from these groups was outrageously good.

I just can’t understand how so many musicians just want to be the same as so many others.”

— Pete Townshend

“A lot of these guys in spandex trousers and hair like that are playing some of the most unbelievable guitar, and you can't really argue with it,” he said. “It's just that sometimes the vehicles seem to leave a little bit to be desired.”

That was true, he thought, even when heavy-metal acts were covering his own songs. He pointed to the band W.A.S.P., which had covered “The Real Me,” one of the tracks from the Who’s Quadrophenia.

“You give them a good song, and they're fuckin’ out there; it's frightening,” he admitted. “But it’s interesting that they picked that song; they picked a song which is a boast, a threat. It's just that the form is limiting, and I suppose part of that I actually respect, because I think that limitations are very, very valuable.

“But I just can’t understand how so many musicians just want to be the same as so many others.”

To Townshend’s point, heavy-metal’s look and sound were becoming homogeneous by the late-’80s end of its reign. About the only good thing he could say was that the music was inspiring youngsters to pick up guitar and develop into young virtuosos.

“Kids have been playing guitar and having lessons from the age of eight, sometimes younger,” he noted. “So when they hit 14 or 15 or 16, they're sort of going past their peak.

“There's some wonderful stuff happening there,” he admitted. “I just wish there was a better medium for it. I wish we had something that was more akin to jazz in its ability to take virtuoso performers and give them a stage, rather than just be hit with little tongue flashings and wagging fingers and legs astride, and waggling very big kind of psychedelic cocks at the audience. So in that sense, I suppose I do despise it.”

There's some wonderful stuff happening there. I just wish there was a better medium for it.”

— Pete Townshend

What he preferred was music that cut its own path. In that respect, he was drawn to the sounds of alternative rock, in particular R.E.M. Though they started out in the early 1980s as architects of southern gothic jangle-pop, by the end of the decade the group had transformed from college-radio darlings to a stadium-ready rock powerhouse through hits like “Orange Crush,” “Stand” and “The One I Love.”

Within Peter Buck’s aggressively strummed Rickenbacker rhythm work, Mike Mills lead-style bass and Bill Berry’s thundering drums, Townshend heard something not unlike the Who nearly two decades earlier.

“I'd trade 50 Def Leppards for…” Townshend began. “That's not enough. I’d trade 150 Def Leppards for one R.E.M. It's as simple as that.

“I heard R.E.M., and my heart just soared. To me, that’s just divine music; I like the sound of it, I think the words are brilliant, I think it's just perfection, and the fact that none of them can kinda go [he mimics shredding] just doesn't interest me at all, because if they wanted to, they could go out and they could hire any one of those guys.

“What's really important is the music, the content, the heart of it.”

Christopher Scapelliti is editor-in-chief of GuitarPlayer.com and the former editor of Guitar Player, the world’s longest-running guitar magazine, founded in 1967. In his extensive career, he has authored in-depth interviews with such guitarists as Pete Townshend, Slash, Billy Corgan, Jack White, Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren, and audio professionals including Beatles engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott. He is the co-author of Guitar Aficionado: The Collections: The Most Famous, Rare, and Valuable Guitars in the World, a founding editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine, and a former editor with Guitar World, Guitar for the Practicing Musician and Maximum Guitar. Apart from guitars, he maintains a collection of more than 30 vintage analog synthesizers.