“When he showed up and did it all for real, it burst my bubble. I was pissed for a little while.” How Eric Clapton survived rock guitar‘s most transformative era and found his way to the blues

Like Jeff Beck and Pete Townshend, Clapton was thrown when Jimi Hendrix arrived on the rock scene

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Jimi Hendrix changed the music so entirely in 1966 that, within months of his arrival in England, established guitarists were wrestling with how to respond. Jeff Beck told Guitar Player, “It was a horrible time, really. Not because of him, but because of the fact that he swept us all aside and put us in a bin.”

Pete Townshend, realizing he could never better or even equal Hendrix’s guitar talents, decided to focus on his song craft. “He came along and, kind of like in early punk, just swept everything aside,” Townshend told Guitar Player in 1989, in terms remarkably similar to Beck‘s. ”I had to learn to write, and it became like a new art, from a new angle.” The results were revealed in the Who’s pioneering 1969 rock opera, Tommy.

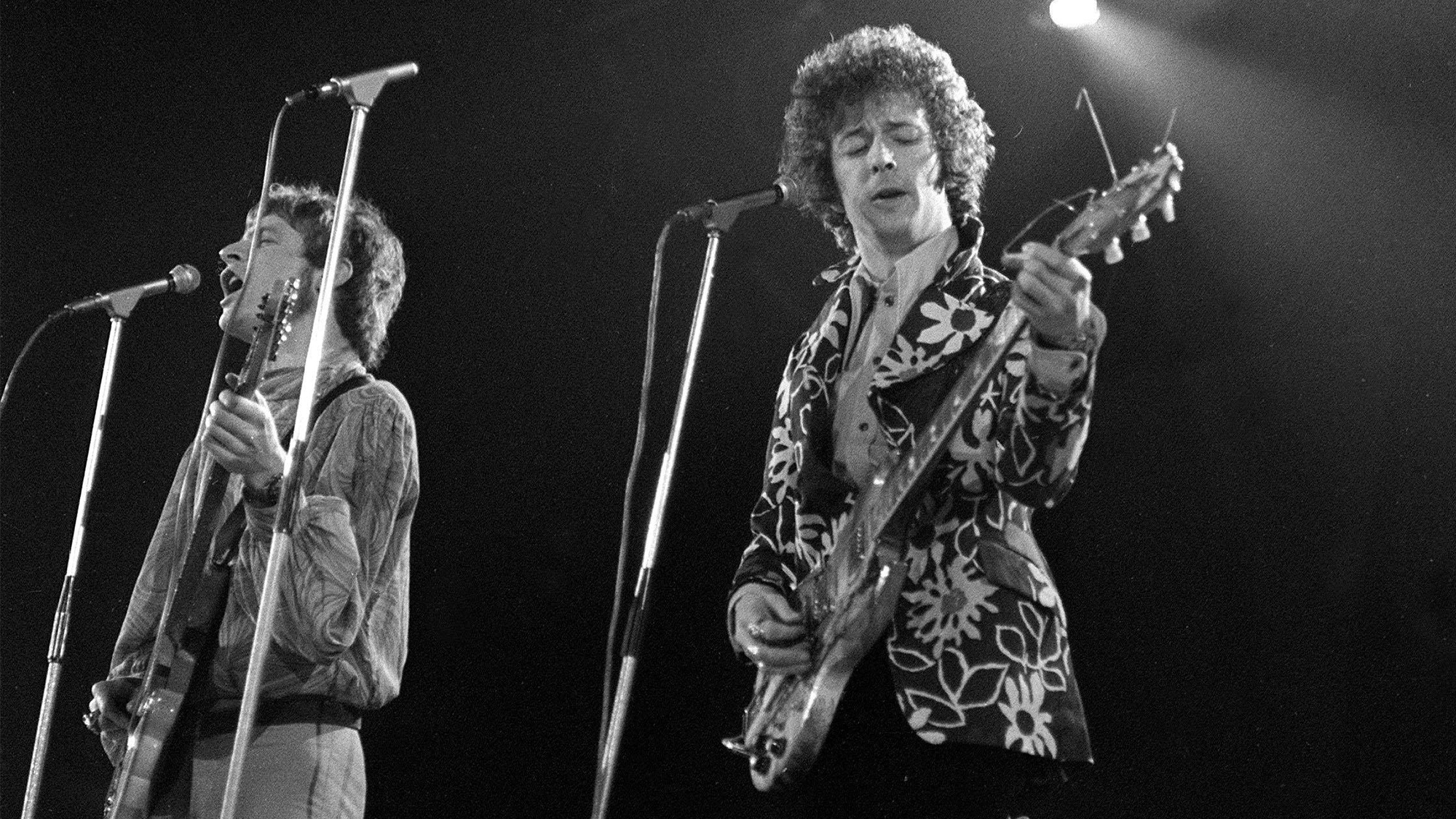

But what about Clapton? From the start, he knew he’d met his match in Hendrix. When, just a few weeks after his arrival in London, Jimi crashed a Cream gig and asked if he could play, Clapton was so stunned by what he heard that he had to leave the stage.

Rather than run from his challenger, Clapton forged a friendship with him. He also permed his hair and plugged his electric guitar into a wah pedal, making him the first, and most visible, guitarist in rock to try to channel Hendrix’s mojo.

But inside, Clapton was as frustrated as Beck and Townshend. That was partly because Hendrix had achieved what he had hoped to when he first saw Buddy Guy perform with a trio in London. Clapton had been so thoroughly convinced by Guy that he left John Mayall and the Blues Breakers in July 1966, at the height of his fame, to form Cream, with the intention of following in Guy’s footsteps with his own power trio.

But Hendrix got their first. What’s more, Hendrix was the real deal, not a copy.

“Although I was with Cream, I had fantasies of incorporating all of that Buddy Guy–like showman stuff into my act,” Clapton told Guitar Player in 2004. “But when Jimi showed up and did it all for real, it burst my bubble. I realized then that I had to look at Cream as a band, and forget about my little solo odyssey.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Clapton was also floored that Hendrix, an American, had come to England to find fame. Like his fellow British musicians, Clapton was looking toward America as the place to stake his claim in rock.

“Cream was cutting Disraeli Gears in New York while he was cutting Are You Experienced in London. When we came back to England, no one wanted to know.”

— Eric Clapton

“What was even more of a shock was that Hendrix was part of America coming to England to take over, while we were all going to America trying to take it by storm,” he said. “Cream was cutting Disraeli Gears at Atlantic Studios in New York while he was cutting Are You Experienced in London. Then, when we came back to England with that album, no one wanted to know, and I was pissed for a little while.”

Speaking of which, Disraeli Gears is the album that most shows Hendrix’s influence on Clapton. “I was full-tilt on the wah pedal for a year-and-a-half,” he says.

But Clapton was also cutting his own path. It was here that his famed “woman tone” came about, the result of rolling off his Gibson SG’s tone control.

“I used the bridge pickup, but with the tone control all the way off, so it was all just bottom end, and then I played on the high strings, getting a really fat tone and feeding back,” he explained. “I just played like that all the time. Even with power chords, there was never any variation in my tone.

“It was much later that I came to the Stratocaster, and I think that was because of Jimi. He could get more tonal variation out of that instrument than I ever thought possible. I knew about the Buddy Holly, thin bridge-pickup sound, but I didn't know that it was possible to get the Strat to sound really big, or get it to feed back in tune-which was very easy with a Les Paul. And then, when I started playing around with the Strat, I realized it was nice to be able to play clean, too.”

“I’ve always thought it was rather funny and ironic when I'd see footage of interviewers actually asking people like John Lee Hooker what the blues is.”

— Eric Clapton

Like Beck and Townshend, Clapton eventually found a path through Hendrix’s scorched earth. Through the stripped-back roots music of Band guitarist Robbie Robertson and the influence of American country guitarist Delaney Bramlett and his group, Delaney & Bonnie and Friends, Clapton was led to the birthplace of the blues and the music of Robert Johnson. Unlike the world of late 1960s blues rock, there was nothing to compete with — just music from which to live and learn.

“The blues is a strange phenomenon,” he concluded in his 2004 chat with Guitar Player. “I’ve always thought it was rather funny and ironic when I'd see footage of interviewers actually asking people like John Lee Hooker what the blues is. I've heard those old guys say some really funny things — either profound or ridiculous.

“My way of putting it is that it's a set of rules imbued with deep emotion. But, of course, that doesn't really describe anything at all. The blues is a strange phenomenon, and I'm certainly not bigger than it.”

Christopher Scapelliti is editor-in-chief of GuitarPlayer.com and the former editor of Guitar Player, the world’s longest-running guitar magazine, founded in 1967. In his extensive career, he has authored in-depth interviews with such guitarists as Pete Townshend, Slash, Billy Corgan, Jack White, Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren, and audio professionals including Beatles engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott. He is the co-author of Guitar Aficionado: The Collections: The Most Famous, Rare, and Valuable Guitars in the World, a founding editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine, and a former editor with Guitar World, Guitar for the Practicing Musician and Maximum Guitar. Apart from guitars, he maintains a collection of more than 30 vintage analog synthesizers.