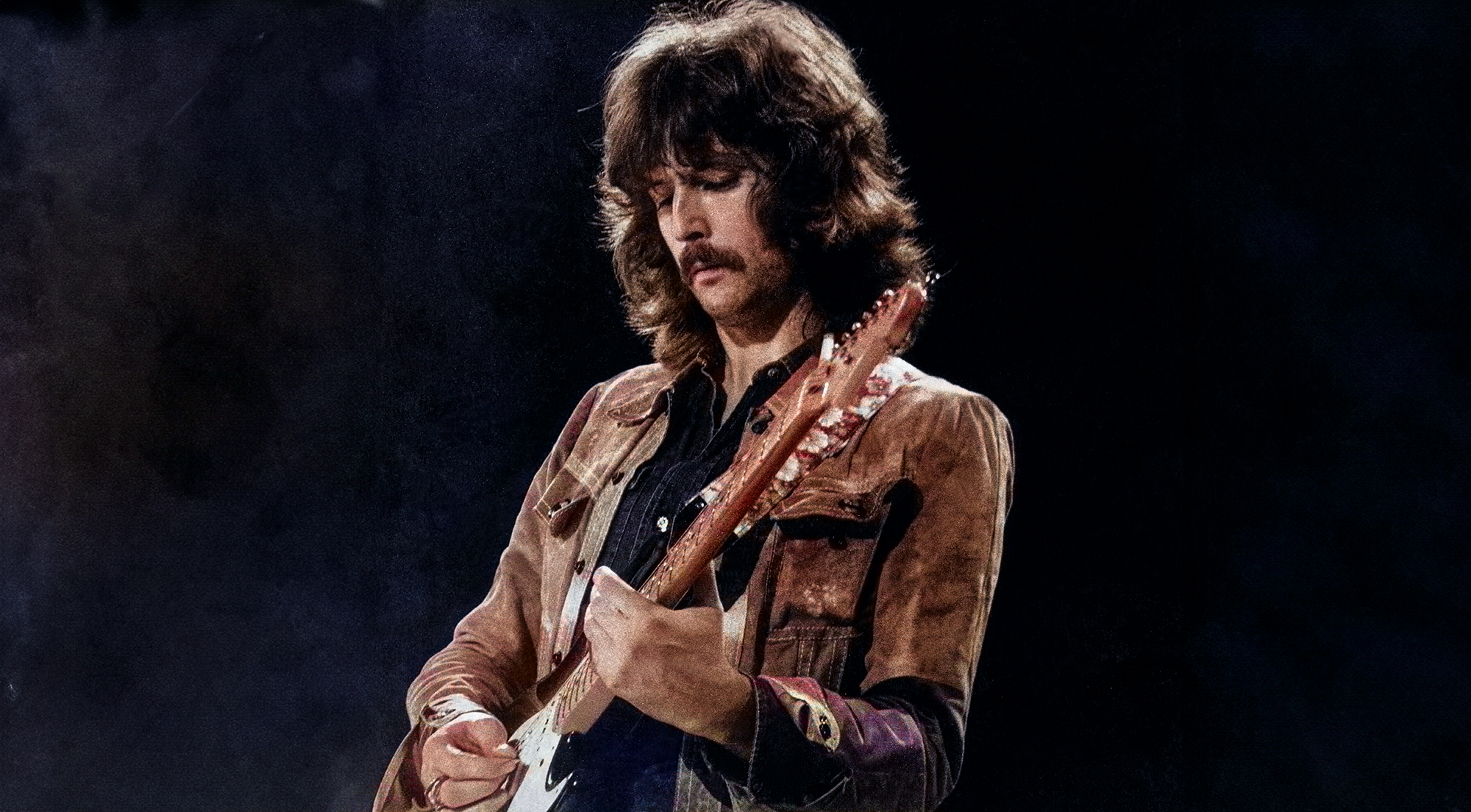

“I’d put this tape on and go into another world. It became my drug.” Eric Clapton on the group he wanted to join so badly that he broke up Cream

The guitarist wouldn’t perform with the act until 1976, at its star-studded farewell concert

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Eric Clapton left the Yardbirds for John Mayall in 1965 because he wanted to play the blues. He left Mayall one year later to form Cream with bass guitarist Jack Bruce and drummer Ginger Backer after seeing Buddy Guy play in London and deciding a blues-rock trio was more to his liking.

Two years later, Clapton was ready to call Cream a day, despite the group's power and influence, and the fact that they were at the top of their game.

The reason? He’d heard a little roots-rock quintet called the Crackers, and was completely taken by their music.

Though they weren't famous by name, the Crackers were far from unknown. They were a group of Canadians with a U.S.-born drummer and had been called the Hawks before Bob Dylan hired them to be his touring group.

From September 1965 through May 1966, they went on the road with him, billed collectively as Bob Dylan and the Band. When Dylan went into seclusion in Woodstock, in upstate New York, they joined him, working as the Crackers, to record what became known upon its release in 1975 as The Basement Tapes.

It was selections from those sessions that Clapton first heard while on the road with Cream around 1967.

“I knew this man in L.A., who was an entrepreneur of different sorts of things,” Clapton recalled. “And he had a tape by a band called the Crackers, and he lent it to me, and I took it on the road with me. And it became my drug.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“When we would get to the end of a gig, Jack and Ginger would go off and do their stuff, and I'd put this tape on, and I'd go into another world, and it was my kind of release.”

By 1968, the Crackers were signed to a label and had a new name — or actually the old name they had with Dylan: the Band. The group consisted of guitarist Robbie Robertson, bassist Rick Danko, keyboardists Richard Manuel and Garth Hudson, and drummer Levon Helm. Their debut album, Music From Big Pink, became a classic thanks to songs like “The Weight,” “This Wheel’s on Fire,” “Tears of Rage” and “I Shall Be Released.”

Rustic, rootsy and pastoral, the Band’s music was 180 degrees removed from the electric guitar–driven blues-rock that Cream were crafting. Listening to their music, Clapton heard his future.

“For someone like me who’d been born in England and worshipped the music from America, it was very tough to find a place to belong in all this,” he said. “And this band that I was listening to on this tape had it all. They were white, but they seemed to have derived all that could from Black music, and they combined it to make a beautiful hybrid.

I wanted to be in the band. So I went and told Jack and Ginger that I couldn't go on anymore. There was something else happening.”

— Eric Clapton

“And for me, it was serious. It was serious, and it was grown up, and it was mature, and it told stories, and it had beautiful harmonies, fantastic singing, beautiful musicianship, without any virtuosity. Just, you know, economy, and beauty.

“And — I wanted to be in the band. So I went and told Jack and Ginger that I couldn't go on anymore. There was something else happening.”

That same year Clapton, like his friend George Harrison, visited the Band in Woodstock.

“I really sort of went there to ask if I could join the band,” Clapton continued. “I mean, I didn't have the guts to say it, you know? I didn't have the nerve. I just sort of sat there and watched these guys work.

“And I remember Robbie saying, ‘We don’t jam. There's no point sitting here and trying to, you know. We just write and work.’ And I was very impressed.”

Impressed enough that he left Cream and — after a brief, failed foray with Blind Faith — recast himself as a roots rocker with his 1970 solo album, Eric Clapton.

He would eventually perform with the Band, in 1976, at the Last Waltz, the group’s historic and star-studded farewell concert held on Thanksgiving Day, November 25, at San Francisco’s Winterland Ballroom. Playing with them in their final concert would be as close as he would get to joining the Band. It was a bookend to his first visit with the group in Woodstock and marked yet another turning point in his music.

“I spent the rest of my career until the Last Waltz, anyway, trying to find ways to imitate what they had. And it was an impossible dream, really, because from where I came from and from where they came from completely different worlds.”

But what Clapton learned from them remained a touchstone for his music going forward.

“It was something to do with a principle that I got from what they did, which was integrity,” he says. “Integrity, and a standard of craft that really didn't bow down to any kind of commerciality. I identified with that, and I adored it.

“And at the same time, it was very hard. It was very hard to kind of make my way with this going on and not be part of it until the Last Waltz. And in some respects, I was very relieved with the Last Waltz, because it meant that there wasn't a Band that I wasn't a part of anymore. And I could just go on and be me, and it was all right.”

Christopher Scapelliti is editor-in-chief of GuitarPlayer.com and the former editor of Guitar Player, the world’s longest-running guitar magazine, founded in 1967. In his extensive career, he has authored in-depth interviews with such guitarists as Pete Townshend, Slash, Billy Corgan, Jack White, Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren, and audio professionals including Beatles engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott. He is the co-author of Guitar Aficionado: The Collections: The Most Famous, Rare, and Valuable Guitars in the World, a founding editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine, and a former editor with Guitar World, Guitar for the Practicing Musician and Maximum Guitar. Apart from guitars, he maintains a collection of more than 30 vintage analog synthesizers.