“We got the guitars out, and then things loosened up.” George Harrison on the 1968 visit with Bob Dylan that changed his future in the Beatles

Dylan's invitation for Harrison to spend Thanksgiving with him in Woodstock forged a friendship that lasted through Harrison's life

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

“If Dylan hadn’t said some of the things he did, nobody else was going to say them,” George Harrison once noted of the folk-rock icon. “Can you imagine what a world it would be if we didn’t have a Bob Dylan? It would be awful.”

At the very least, a world without Dylan would have made a poorer existence for Harrison. While much is made of his long and complicated friendship with Eric Clapton — one that saw them duel with guitars for the hand of Pattie Boyd — Harrison’s relationship with Dylan was something approaching a spiritual connection.

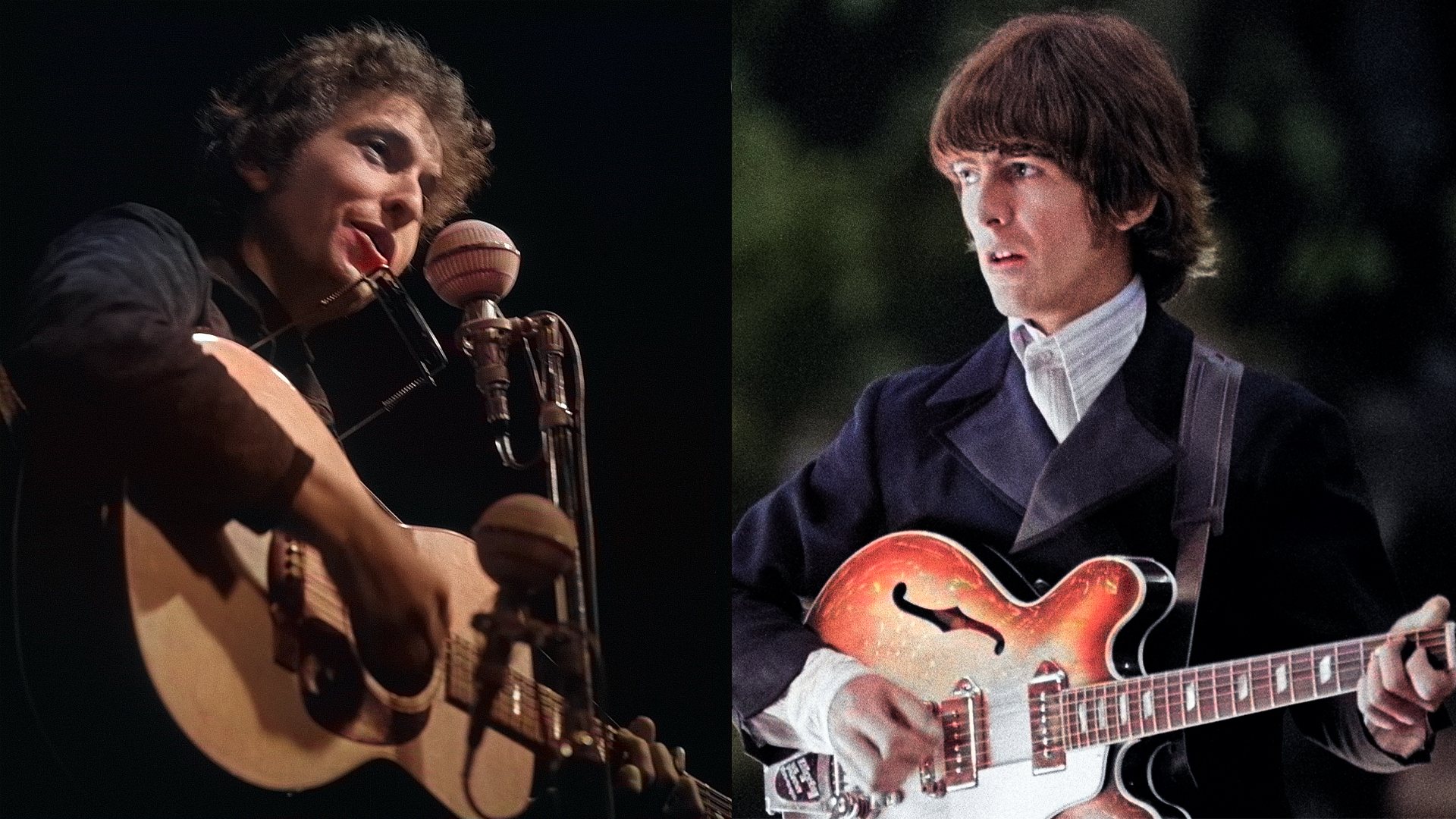

Harrison had first heard the folk icon while the Beatles were in Paris in 1964, after a DJ gave a copy of The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan to Paul McCartney. All four of the Fabs fell in love with the album, which included classic tracks like “Blowin’ in the Wind,” “A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall” and “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right.”

“He was doing what everybody else tried to do after him — saying whatever he wanted to say in song,” Harrison wrote of Dylan in his 1980 autobiography, I Me Mine.

The Beatles and Dylan met later that year, in August, while the group was performing in New York. Although, initially, Lennon bonded with Dylan more closely than the others, Harrison’s quiet nature resonated with the folk guitarist’s reserved personality. Harrison later told Rolling Stone that Dylan “was like me in many ways, a bit of a loner.”

Dylan felt the connection too. Unlike Lennon, Harrison wasn’t copying his music or sartorial style. Dylan also seemed to sense that Harrison wasn’t getting his due in the group, where his songwriting talents were overshadowed by Lennon’s and McCartney’s.

“George got stuck with being the Beatle that had to fight to get songs on records because of Lennon and McCartney,” Dylan noted to Rolling Stone. “Well, who wouldn’t get stuck?

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“If George had had his own group and was writing his own songs back then, he’d have been probably just as big as anybody.”

From the start, Harrison had been the odd man out in the Beatles. The youngest member of the group, he stood in the creative shadow of Lennon and McCartney, whose songwriting talents outshone his own.

His embrace of the sitar in late 1965 was the first sign that Harrison was a stray among the flock. His attempts to learn the instrument marked the start of his journey away from guitar. Between late 1966 and the summer of 1968 he studied the instrument with sitar master Ravi Shankar, and only picked up the guitar when required for recording.

His long walk back to the instrument began in June 1968, while he was in California filming Shankar for Raga, the 1971 movie about the sitarist released by Apple Films. Despite two years of rigorous sitar study, Harrison realized he would never come close to mastering the instrument.

Flying home to England, he made a stop in New York City, where, by coincidence, he happened upon his pal Clapton and the guitarist who had come to define everything that rock guitar was in 1968: “I checked in the hotel in New York,” Harrison wrote. “Jimi Hendrix and Eric Clapton happened to be staying there.”

Enjoying the familiarity of his fellow guitarists, it seemed to Harrison that he had at last found a place where he fit in, and where he was accepted as an individual, not as a Beatle.

“I thought, Well, maybe I’m better off to get back into being a guitar player, songwriter, whatever I’m supposed to be,” he recalled. “Because I’m never gonna be a sitar player. Because I’ve seen a thousand sitar players in India who are twice as better than I’ll ever be!”

He seemed very nervous and I felt a little uncomfortable — it seemed strange, especially as he was in his own home.”

— George Harrison

But Harrison was still insecure about his contributions to the Beatles, and the growing creative tensions within the group were fraying his nerves. That September, seeking the companionship he’d enjoyed with Hendrix and Clapton, he invited Clapton to perform the lead electric guitar parts on the Beatles’ recording of his song “While My Guitar Gently Weeps,” one of four songs he had on the group's 1968 White Album. It was the first time any of the Beatles had dared to make a move without the approval of the others.

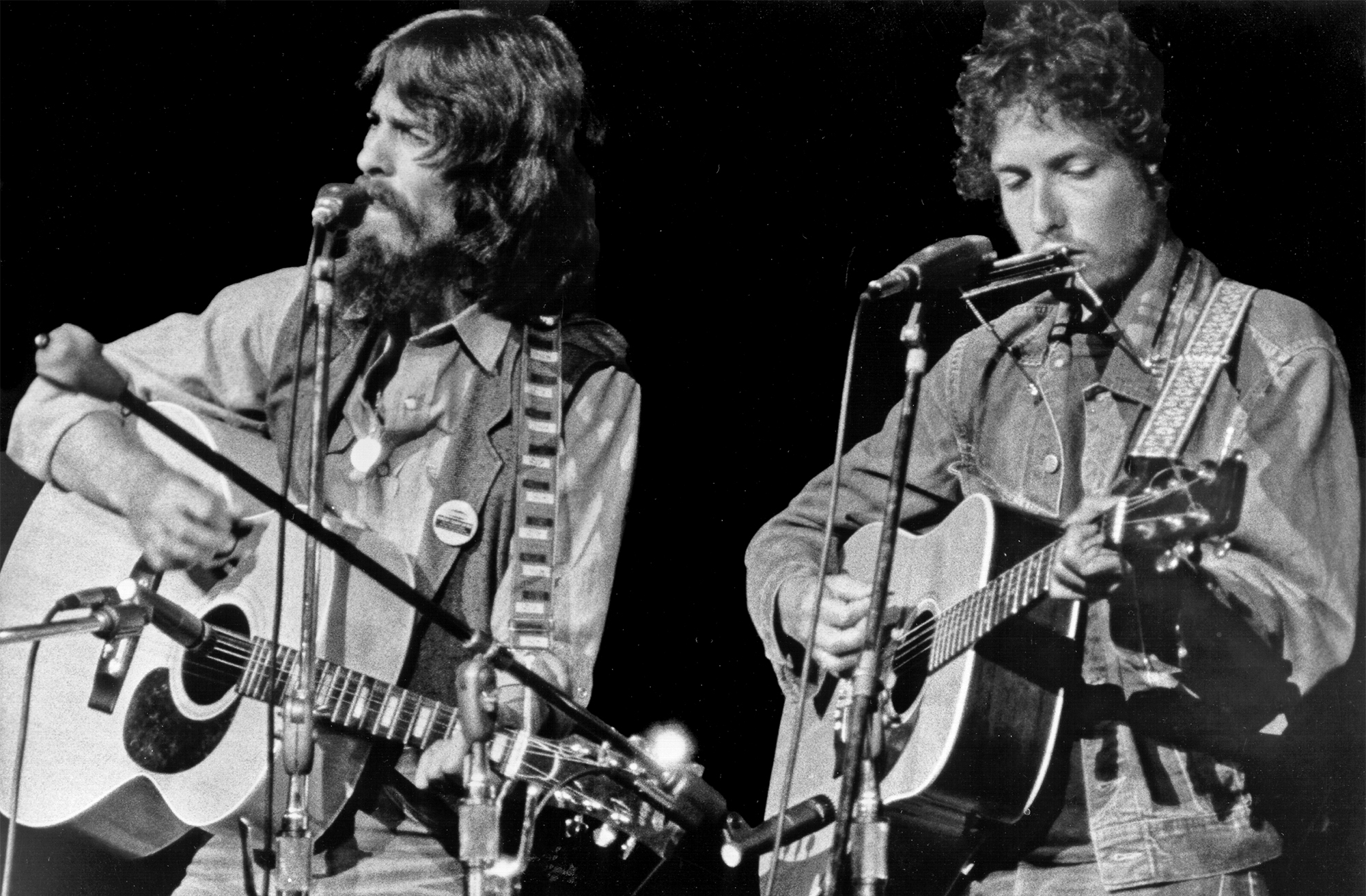

But his sense of confidence was about to get a huge boost. In November, Dylan invited him to spend Thanksgiving in Woodstock with him and the Band, the Canadian-American roots group that had briefly served as his backup band. Harrison eagerly accepted. Beyond his love for Dylan's music, he, like Clapton, was taken by the fluid electric lead guitar work of the Band’s guitarist, Robbie Robertson, which approximated the sound of slide guitar.

It was there, in Woodstock, that Harrison and Dylan made their lifetime connection during a visit that lasted several days. But in spite of their familiarity, things didn’t begin smoothly.

“I was hanging out at his house, with him, [his wife] Sara and his kids,” he wrote in I Me Mine. “He seemed very nervous and I felt a little uncomfortable — it seemed strange, especially as he was in his own home.

Around the third day, he wrote, “we got the guitars out, and then things loosened up.” Harrison encouraged his host to give him some lyrics, something along the lines of “Subterranean Homesick Blues,” his rapid-fire proto-rap 1965 folk-rock tune.

“I was saying to him, ‘Write me some words,’ and thinking of all this: Johnnie‘s in the basement, mixing up the medicine type of thing, and he was saying, ‘Show me some chords, how do you get those tunes?’”

Before too long, they were composing the music and words to their first of two songs: “I'd Have You Anytime.”

“I started playing chords, like major sevenths, diminisheds and augmenteds,” Harrison wrote, “and the song appeared as I played the opening chord and then moved the chord shape up the guitar neck. The first thing I thought was: Let me in here / I know I’ve been here / Let me into your heart.

“I was saying to Bob, ‘Come on, write some words.’ He wrote the bridge: ‘All I have is yours / All you see is mine / And I’m glad to hold you in my arms / I’d have you anytime.’

“Beautiful! — and that was that.”

Years later, in Martin Scorsese’s documentary, George Harrison: Living in the Material World, his wife, Olivia, said he was “talking directly to Bob” in the song.

“He’d seen Bob, and then he’d seen Bob another time, and he didn’t seem as open. And so that was his way of saying, ‘Let me in here, let me into your heart.’

“And he was very unabashed and romantic about it in a sense. I found that he had these love relationships with his friends. He loved them.”

Warmed by his experience in Woodstock, Harrison returned to England with a new sense of purpose and confidence. It was not lost on Harrison that, by writing with Dylan, he had achieved something his Dylan-loving bandmates had not.

He was very unabashed and romantic about it in a sense. I found that he had these love relationships with his friends. He loved them.”

— Olivia Harrison

Roughly a month later, in early January 1969, as the Beatles got to work recording Let It Be, Harrison began to assert himself for the first time. Unhappy with McCartney’s bossiness and the sour mood of the sessions, on January 10, he walked out and briefly quit the group.

Harrison’s departure was a wake-up call to the others. Almost immediately afterward, Lennon and McCartney had a discussion about how they had disregarded his musical contributions for years. When Harrison returned, he had a new sense of purpose and self-assuredness, which became apparent with the recording of the group's final album, 1969's Abbey Road. Among its many tracks, Harrison's — "Something" and "Here Comes the Sun" — stand out as two of its finest.

That fact wasn't lost on his bandmates. In September 1969, Lennon put forth a proposal that would have given himself, McCartney and Harrison four songs apiece on any future Beatles album. Given what had transpired in the past, it was a remarkable show of equity, although unfortunately, one that came too late.

Christopher Scapelliti is editor-in-chief of GuitarPlayer.com and the former editor of Guitar Player, the world’s longest-running guitar magazine, founded in 1967. In his extensive career, he has authored in-depth interviews with such guitarists as Pete Townshend, Slash, Billy Corgan, Jack White, Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren, and audio professionals including Beatles engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott. He is the co-author of Guitar Aficionado: The Collections: The Most Famous, Rare, and Valuable Guitars in the World, a founding editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine, and a former editor with Guitar World, Guitar for the Practicing Musician and Maximum Guitar. Apart from guitars, he maintains a collection of more than 30 vintage analog synthesizers.