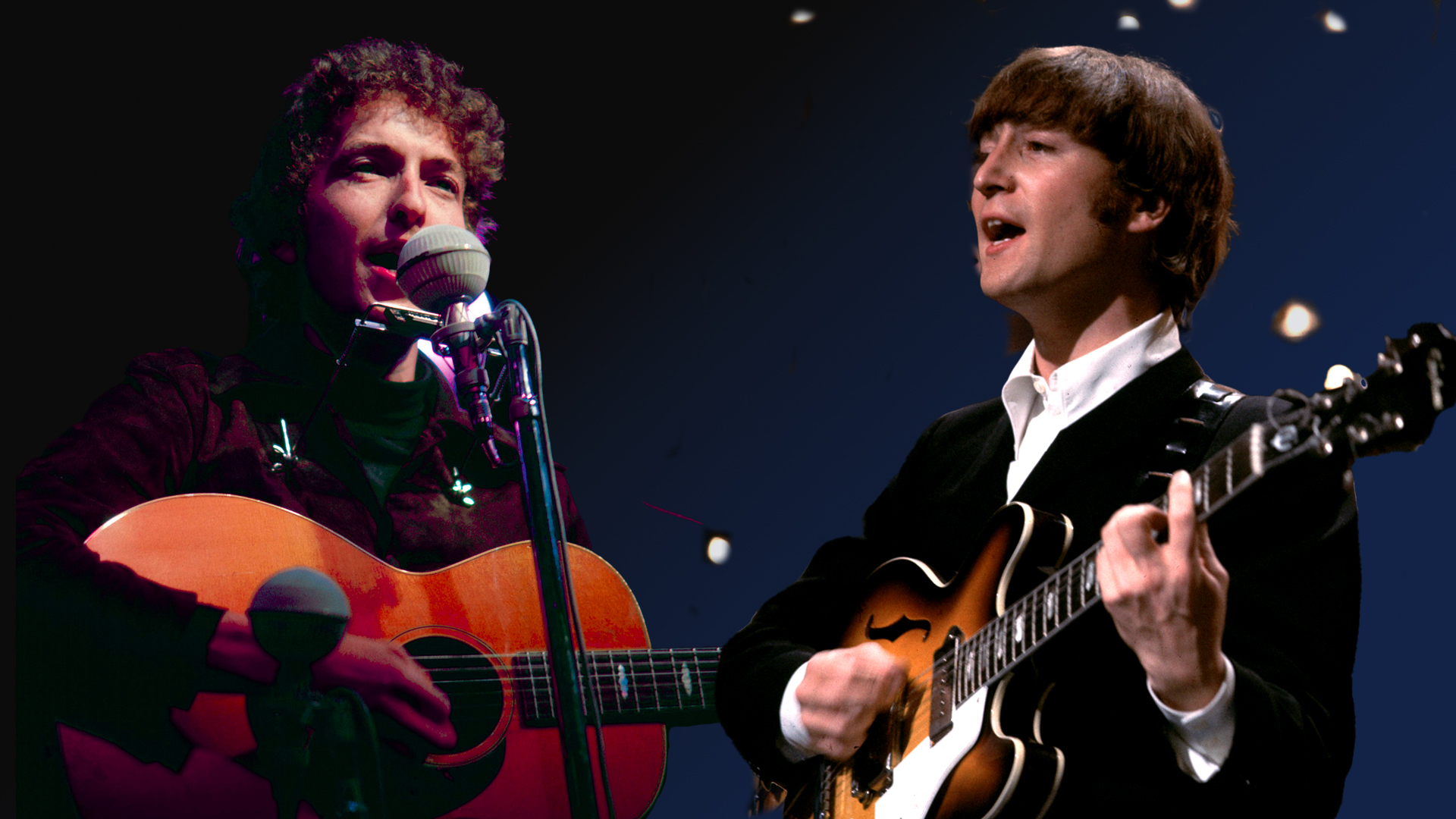

“Those aren’t the words. It’s ‘I can’t hide.’ ” How a misheard John Lennon lyric led Bob Dylan to meet the Beatles and change both their destinies

Drawn together by mutual admiration, the Beatles and Dylan would push each other to new phases of their artistry. And it started with one song

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In the Beatles’ evolution from rock and rollers to psychedelic rock innovators, no figure looms larger than Bob Dylan. It was Dylan who introduced the group to pot, a drug that would have a transformative affect on their artistry, leading them to LSD and the psychedelia of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.

It may not be an exaggeration to call August 28, 1964 one of the most significant dates in Beatles history. It was on that day that the Fab Four met the Voice of a Generation, who. turned them on to pot.

At the dawn of 1964, as Beatlemania descended on the U.S. shores, Dylan was the indisputable leader of the folk music movement centered in New York City’s Greenwich Village. He’d just released his third album, The Times They Are A-Changin’, his first LP to feature entirely original compositions. As with his previous albums, Dylan focused on social themes, including poverty and racism.

But as he prepared to make his next album, the aptly titled Another Side of Bob Dylan, he was eager to leave behind the socially conscious “finger-pointin’ songs,” as he called them, and write about love and personal matters, themes more common to pop than to folk.

Although Dylan had originally dismissed the Beatles’ music as “bubble-gum,” he was floored by “I Want to Hold Your Hand,” the single that had helped the group break through in the U.S. when it was released in late December 1963. Somehow, Dylan didn’t take notice of the song until the following February. He and a few friends had packed up a station wagon and were headed across the country to meet with “people in bars, miners,” Dylan said, in an attempt to drum up inspiration to help his lyrics move beyond topical themes to matters of immediate personal concern.

They were in Colorado when “I Want to Hold Your Hand” came on the radio. Dylan “nearly jumped out of the car,” recalled his tour manager Victor Maymudes, who was along on the ride.

“Did you hear that?” Dylan asked his friends. “Fuck! Man, that was great!”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

When he returned to New York City that March, the folksinger promptly bought his first electric guitar, an instrument with which he would ultimately transform his music and make his break from folk. “They were doing things nobody was doing,” he recalled of the Beatles, explaining their influence on him and his decision to go electric.

“Their chords were outrageous, just outrageous, and their harmonies made it all valid … I knew they were pointing the direction of where music had to go.”

Remarkably, almost simultaneously, Dylan had made his own deep impression on the Beatles. That previous January, during an 18-day residency at the Olympia Theatre in Paris, the group had discovered his second album, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, and were captivated by it.

“I think Paul got the record from a French DJ,” John Lennon recalled. “And for the rest of our three weeks in Paris we didn't stop playing it. We all went potty on Dylan.”

Given their admiration for one another, the Beatles and Dylan were eager to meet. As it happened, they had a mutual friend, journalist Al Aronowitz. In spring 1964, while in England on assignment for the Saturday Evening Post, Aronowitz had met Lennon and subsequently covered the Beatles’ return to the U.S. for a tour that August. When the road show arrived in New York, Aronowitz arranged for the meeting to take place.

On August 28, as the group returned to its suite at the Delmonico Hotel in Manhattan following a performance at the Forest Hills Tennis Stadium in Queens, Aronowitz rode in from Woodstock with Bob Dylan in a blue Ford station wagon driven by Maymudes. Parking around the corner from the hotel, the men barreled through the throng of teenagers surrounding the Delmonico and made their way up to the floor where the Beatles and their entourage were entrenched.

There they were met by a battalion of police assigned to protect the group, and a throng of reporters, deejays and performers — including folk artists the Kingston Trio and Peter, Paul & Mary — who were waiting to meet with the Beatles.

The three men were quickly whisked into a room, where the Beatles were waiting with their manager, Brian Epstein, and a few others. Introductions were made. Dylan was offered a drink and asked for cheap wine. With none available, the Beatles sent their roadie Mal Evans out to buy some.

While they waited for Evans to return, Dylan suggested they smoke some weed. He fully expected the Beatles were into pot. Aronowitz had even brought his own personal stash along as a special treat for them.

When they told Dylan they didn’t touch the stuff, he was perplexed.

“But what about the song?” he asked.

“What song?” John replied.

“The one that goes, ‘And when I touch you I feel happy inside,’” he said, referencing “I Want to Hold Your Hand.” “‘I get high, I get high, I get high.’”

The Beatles looked around at one another.

“Those aren’t the words,” Lennon finally replied. “It’s ‘I can’t hide.’”

Dylan may have got the words wrong, but he wasn't entirely incorrect in assuming the Beatles were experienced pot smokers. They had tried it once before, while performing in Hamburg in 1960, but were unimpressed by its effects.

“I remember we smoked it in the band room in a gig in Southport and we all learnt to do the Twist that night, which was popular at the time,” Harrison recalled in the Beatles’ Anthology. “Everybody was saying, ‘This stuff isn’t doing anything.’

"It was like that old joke where a party is going on and two hippies are up floating on the ceiling, and one is saying to the other, ‘This stuff doesn't work, man.’”

Now, however, with their hero offering to turn them on — and despite the heavy police presence beyond their door — the Beatles decided to give pot another chance. After making sure the room was secure, Dylan rolled a joint and gave it to Lennon, who nervously handed it off to Ringo Starr.

“My royal taster,” Lennon said.

Starr took a puff and continued dragging on it, apparently unaware he was supposed to pass the joint along. Upon consuming it, he announced that it had no effect on him. Meanwhile, Dylan and Aronowitz had rolled joints for each of the others, including Epstein.

“Soon, Ringo got the giggles,” Aronowitz wrote years later, and “the rest of us started laughing hysterically at the way Ringo was laughing hysterically.”

Eventually, the entire group was experiencing its first real high.

McCartney was particularly struck by the drug’s effect. He recalled feeling like he was “thinking for the first time” and told Evans, who had since returned with Dylan’s cheap wine, to follow him around with a notebook and write down everything he said.

“Mal gave me this little slip of paper in the morning, and written on it was, ‘There are seven levels!’” he said. “And we pissed ourselves laughing.”

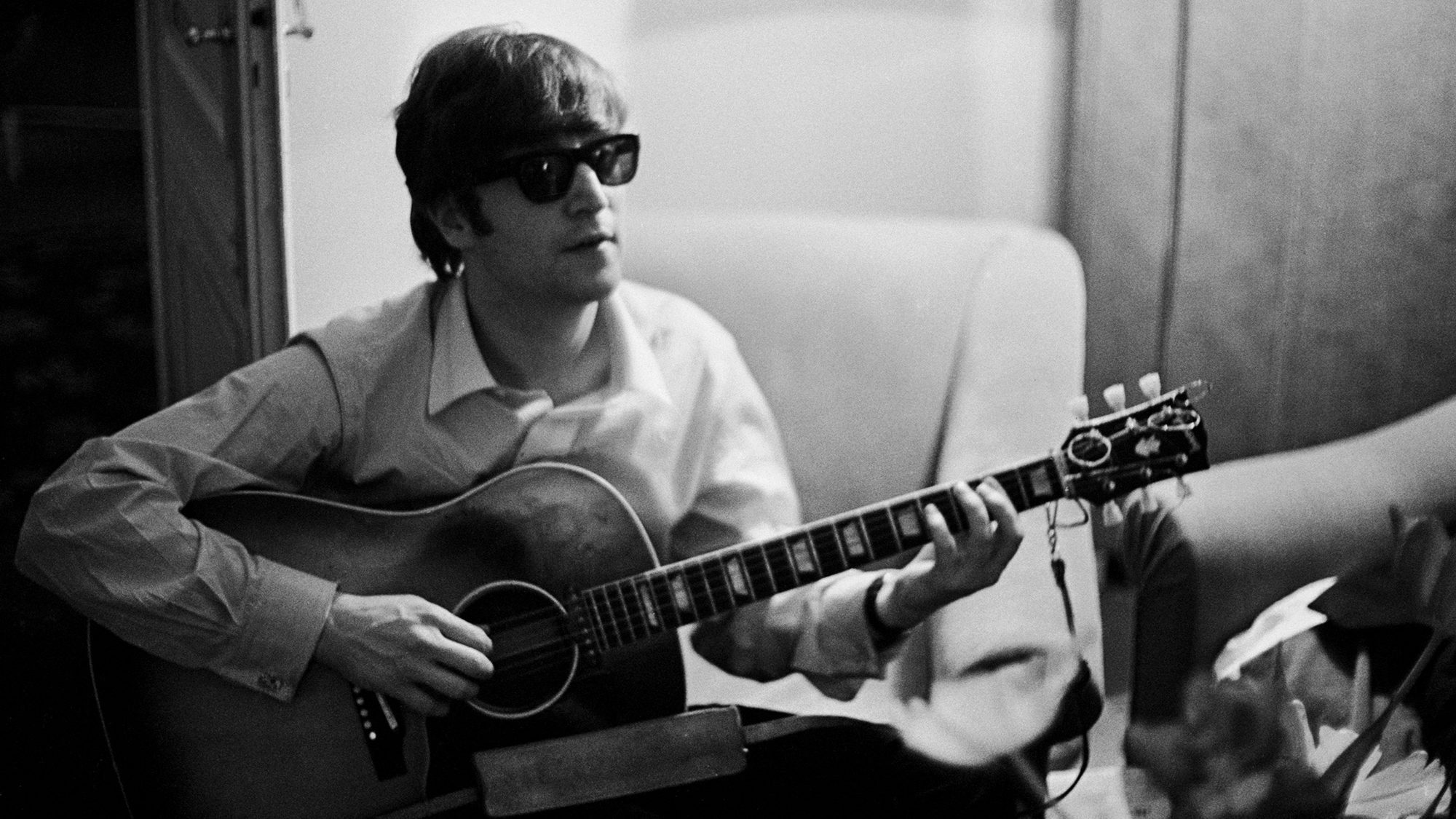

Following their meeting with Dylan, the Beatles moved in a more decisive folk direction. Their next album, Beatles for Sale, saw Lennon put his Gibson J-160E acoustic-electric to greater use on folk-influenced songs like "No Reply" and "I'm a Loser," tunes that, like Dylan's, were confessional in nature.

The trend would continue over the next year on Help! — where Lennon played a Framus Hootenanny 12-string acoustic on the highly personal "Help!" and "You've Got to Hide Your Love Away" — and on Rubber Soul's "Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)."

Equally notable, the Fab Four became confirmed potheads. Ultimately, marijuana would help Lennon dig deeper into his psyche and write some of his most personal songs. It would also lead the group to explore new ways of presenting their music.

“You would smoke a joint and then sit down at the piano and think, Oh, this might be a great idea!” McCartney explained in his autobiography, Many Years from Now.

The Beatles’ pot use peaked in 1965 during the making of their second feature movie, Help!, where they smoked it to help pass time on the set waiting for filming to begin.

“The Beatles had gone beyond comprehension,” Lennon said. “We were smoking marijuana for breakfast. We were well into marijuana and nobody could communicate with us, because we were just glazed eyes, giggling all the time.”

The Beatles’ effect on Dylan would become evident on his next album, Bringing It All Back Home, half of which featured him backed by an electric rock band. Among the record’s tracks is “Mr. Tambourine Man,” a song whose surreal and at times psychedelic-inspired lyrics have often been interpreted as a tribute to LSD.

Dylan’s embrace of electric rock, along with the development of his intimate, confessional style of songwriting, eventually marked the end of his involvement with the folk scene. The final break came the following July 1965, at the Newport Folk Festival, when he performed with an electric band, leading the folk movement to disown him.

While his new sound alienated his folk-loving admirers, not all of them were put off by it. Many stuck with Dylan as he continued his evolution from folk singer to rock artist. In the process, they discovered that, drugs and fashion aside, the hippie lifestyle was not so different from that of the folkies. For that matter, both shared common ideals of peace, ecology, racial harmony and sexual equality.

“The hippies went for the rock and roll of the British Invasion groups and of Bob Dylan after he scandalized the folk purists by adopting the electric guitar,” Charles Perry writes in The Haight-Ashbury: A History. “ A lot of hippies, in fact, were folkies who had followed Dylan in his switch to rock.”

Christopher Scapelliti is editor-in-chief of GuitarPlayer.com and the former editor of Guitar Player, the world’s longest-running guitar magazine, founded in 1967. In his extensive career, he has authored in-depth interviews with such guitarists as Pete Townshend, Slash, Billy Corgan, Jack White, Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren, and audio professionals including Beatles engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott. He is the co-author of Guitar Aficionado: The Collections: The Most Famous, Rare, and Valuable Guitars in the World, a founding editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine, and a former editor with Guitar World, Guitar for the Practicing Musician and Maximum Guitar. Apart from guitars, he maintains a collection of more than 30 vintage analog synthesizers.