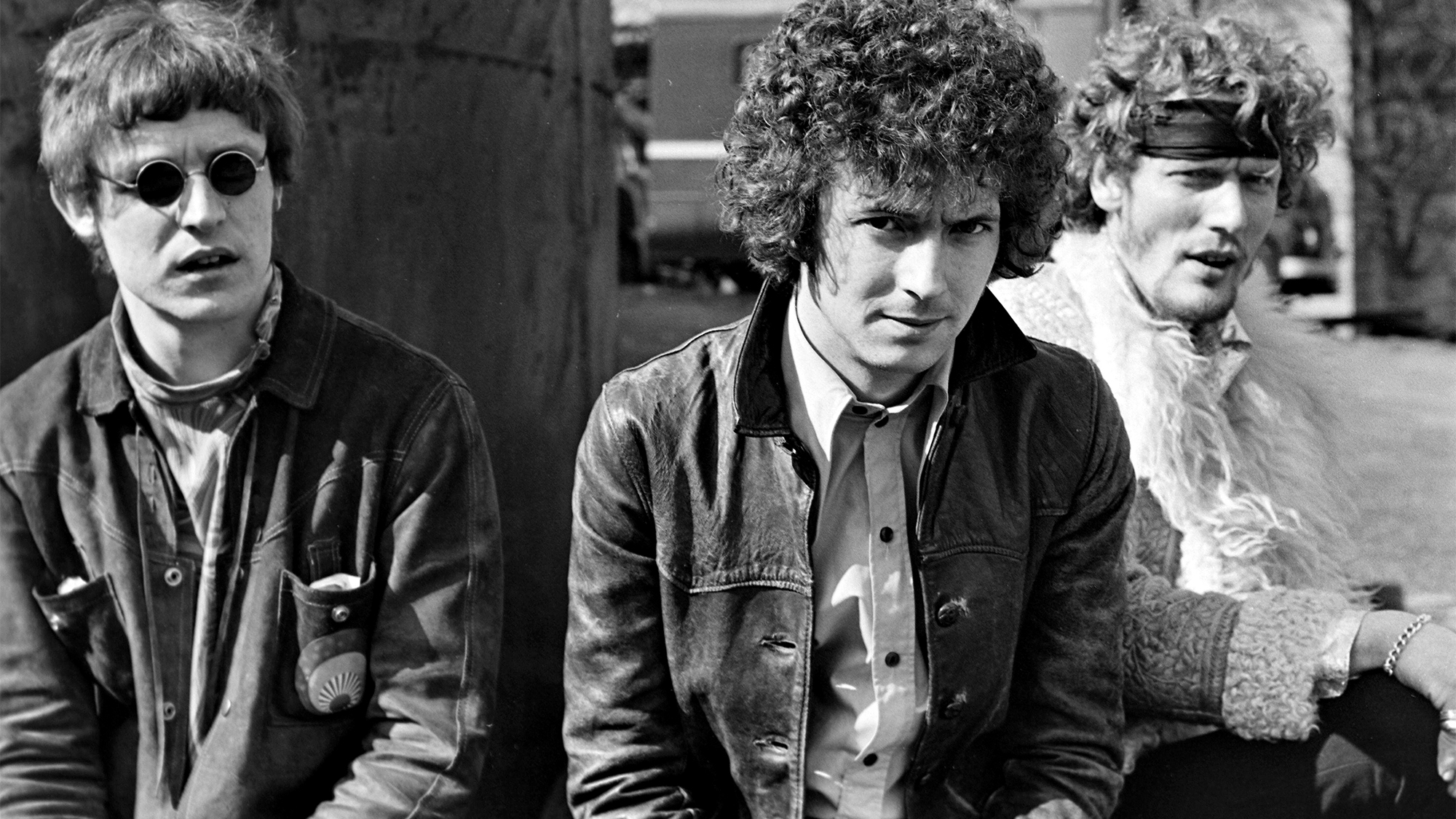

“It was magic. We were just jamming that day, but blues were very common to all of us.” Jack Bruce on the day he met Eric Clapton and how the guitarist changed his way of listening and playing

Bruce recalled the very first jam between Cream's future members at the Windsor Jazz Festival

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Cream were many things to many people, but it seems few could agree on exactly what genre the power trio belonged to.

Eric Clapton reportedly joined thinking it would be a blues trio similar to Buddy Guy’s. Jack Bruce considered the act a jazz trio. Meanwhile, Jethro Tull’s Ian Anderson has credited the band with the birth of progressive rock.

As Clapton himself told Guitar Player in a 1967 interview, “Our music cannot be categorized, because a lot of the material we play is not blues — it’s another thing completely, probably brand new.“

The roots of that “another thing” were the main discussion point in our July 1985 interview with Bruce. Over the course of it, the bassist revealed previously unknown facts about the formation of Cream, and made other statements that he contradicted elsewhere.

For instance, Bruce has stated in other interviews that Clapton thought he was getting a Buddy Guy–style blues trio when Cream formed, only to learn that Bruce and Baker were much more jazz-oriented in their approach, dating back to their time in the Graham Bond Organization.

But as he claims here, Clapton considered himself not a blues guitar player but a rock guitarist — quite a contradiction considering he left the Yardbirds for John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers because he was devoted to playing blues.

For that matter, Bruce didn’t just think of Cream as a jazz-rock band — he considered the trio a true jazz group.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

And while Bruce didn’t mention it, after Clapton announced he was departing Cream in 1968, less than two years after it formed, the band’s management did attempt to keep it going by hiring Rory Gallagher. He declined, deciding he would rather go his own musical direction. “He felt that he would never be his own man,” his brother Dónal concluded.

Given the lack of information on record in the early days of Guitar Player magazine, the interviewer, GP associate editor Tom Mulhern, took Bruce back to the very beginning — his first meeting with Eric Clapton.

Where did you first meet Eric Clapton?

At the Windsor Jazz Festival in ’64 or ’65. He was playing with the Yardbirds, and I was with the Graham Bond Organization. We had a kind of jam at some point in this festival, and Eric was involved.

It was the first time I had actually heard of him, and I was very impressed. I think it was Graham on organ, myself on bass, Ginger Baker on drums, Eric, and some of the Yardbirds — it was so long ago, I don’t really remember who. I was playing electric bass by then — a Fender six-string.

Why did you use a six-string bass?

Well, the Graham Bond band didn’t have a guitarist. It was organ, tenor sax, bass and drums. I played six-string because I was able to do some guitar-like things at the same time. I used that bass in the early days of Cream. It was on the first record [1966’s Fresh Cream], and maybe part of the second one [1967’s Disraeli Gears].

After the festival, did you get together with Eric right away?

No. We were both in busy bands, both working very hard. But Eric used to come to Graham’s gigs. We were a cult band, even among musicians at that time.

But you did record together as the Powerhouse.

Yeah, it was before Cream. We had Eric, myself, Steve Winwood and Pete York on drums. [Ben Palmer played piano, and Paul Jones played harp.] A producer from Elektra Records, Joe Boyd, asked me to do it.

There were no thoughts of making a band at the time, but it probably helped to make the Cream thing happen later. [Bruce seemed to forget that Cream were already together but working in secret at the time of the recording.]

In fact, the more I think about it, the Cream was a jazz band... and maybe that was the root of the problem with the band.”

— Jack Bruce

How did the idea of forming a group come about?

Well, I left the Graham Bond Organization — point of the knife, in fact, from Ginger. [laughs] We had a kind of fight. I played with John Mayall for a while, and I joined Manfred Mann. Ginger had the idea to form a band with Eric. Eric agreed, but only provided that I was in it, too. He was a fan of my singing, in particular. I was approached by Ginger, and we then went to his house in Neasden [a suburb of northwest London], set up our equipment, and played.

It was magic. We were just jamming that day, but blues were very common to all of us. And Ginger and I had been playing together for some time as a jazz rhythm section.

In fact, the more I think about it, the Cream was a jazz band — the only jazz band to go Platinum so far. [laughs] I think that’s what it was, and maybe that was the root of the problem with the band. Yeah, it was a jazz band.

With a blues guitarist.

We often used to talk, and Eric didn’t consider himself a blues guitarist then. He thought of himself more as a rock player. He certainly never considered himself a jazz player.

After your first jam with Eric at Ginger’s house, what was your impression?

Well, Eric at that time was a very outstanding musician. Obviously, when I’m playing with people, that’s the only thing that matters to me, not so much the way they play their axe. When we were traveling to concerts or clubs in the early days, we would have at least as good a time in the car as we would onstage. We had a record player in the car, and so we put on records and sang our hearts out on the way to gigs.

I was always very impressed by Eric’s ear. Obviously, his guitar playing was something else, and he was playing like no one else — certainly in Britain.

But then I also played a lot with John McLaughlin around that time, so it’s not a question of technique or the way that one attacks one’s instrument. It was a question of musicianship, and for me, Eric definitely had that from the word go.

As you worked more with Eric, did you find that it affected the way you played as a bassist?

Oh, much more than that. Eric introduced me to a whole new way of listening to things. I was always a kind of musical snob.

For instance, when I started out, I was a very serious double-bass player, and I never would have considered playing anything that for me wasn’t purist jazz. I was asked to join Alexis Korner’s Blues Incorporated, and I went down to hear the band with Charlie Watts on drums, Cyril Davies on harmonica, Dick Heckstall-Smith on tenor sax, Alexis on guitar, and so on. And I remember thinking that it was a rock and roll band. [laughs] I was a real purist.

He opened my ears to something that I may never have even heard otherwise. And he made me listen to certain things in a certain way.“

— Jack Bruce

I was very fortunate in meeting Eric because he expanded my listening. He introduced me to the Delta blues players, for instance: Skip James, Robert Johnson. Eric gave a lot of credit to Black guys. The blues guys were really ripped off by a lot of white musicians, and that hasn’t changed.

But over the years, Eric has actually exposed guys like Skip James, who was great back in the ’20s, but wasn’t really well known in the ’60s. Eric introduced a lot of people to guys like Robert Johnson, B.B. King, Bob Marley and so on.

He opened my ears to something that I may never have even heard otherwise. He made me listen to different things that have proved very important in my development. And he made me listen to certain things in a certain way.

I had been working on the way I played for some time, and had gotten into a lot of trouble because I believed that the bass could do certain things. Instead of just playing root notes, the bass could be a melodic instrument in a band. It had been my belief since I was 16 or 17, although I encountered problems from people who didn’t understand what I was trying to do, and I got fired from bands.

Eric didn’t change the way I played the bass, but he opened my ears to a lot of things I might have missed.

Tom Mulhern worked at Guitar Player magazine for over 13 years and has contributed to Guitar World, Guitar, Guitar Shop, Billboard, Musician, and more. He has edited a number of books, including Bass Heroes: Thirty Great Bass Players, Concert Photography: How To Shoot And Sell Music-Business Photographs, and contributed chapters to The Gibson and 100 Years Of Gibson Guitars. Visit his website here.

- Christopher ScapellitiGuitarPlayer.com editor-in-chief