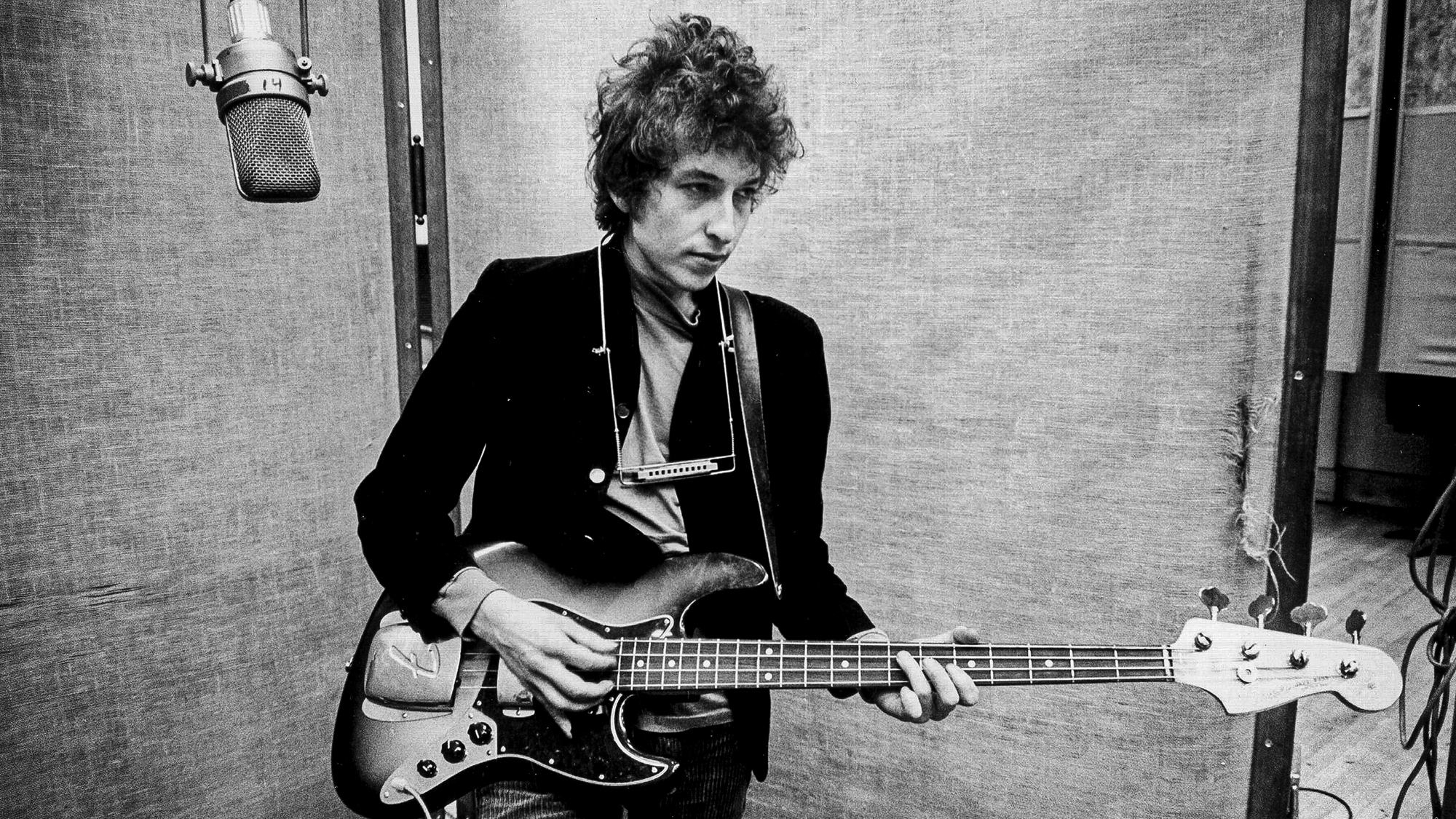

“I was packing up to leave when Dylan asked, ‘Where’s he going?’ and I wound up playing on the whole album.” The guitarist Bob Dylan insisted he had to have for his country music breakthrough

When Dylan's session guitarist failed to show up on ‘Nashville Skyline,’ it opened the door for a newcomer who would go on to have a successful career of his own

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

“I don’t want another guitar player. I want him!”

“Those were the nine words that completely changed my life,” Charlie Daniels recalled of Bob Dylan’s proclamation to producer Bob Johnston after hearing the relatively new studio musician play on the first 1969 Nashville Skyline session. “That just about blew my mind when I heard that! It was incredible news to me.

“Dylan’s regular guitarist wasn’t available that day, so Bob [Johnston], who was one of my dearest friends, had contacted me. I was only supposed to stay for one song, but as soon I finished, I was packing up to leave when Dylan asked Bob, ‘Where’s he going?’ and I wound up playing on the whole album.”

The results of those very special sessions include the songs, “I Threw It All Away,” “Tonight I’ll Be Staying Here With You,” “Country Pie” and “Lay Lady, Lay.” Daniels’ superb musicianship not only led to him being invited to play on Dylan’s next two albums, Self Portrait and New Morning but also brought him studio work with Ringo Starr, Leonard Cohen, Pete Seeger, the Marshall Tucker Band and others.

However, Daniels — who died in 2020 — freely admitted, “I realized early on that I wasn’t cut out to be the quintessential studio musician. From the time I was a child, I dreamed of getting up onstage and entertaining people.”

Born in Wilmington, North Carolina, on October 28, 1936, Daniels convinced his parents to buy him a cheap guitar while still a child.

“It was an old Kay with a large neck, which was difficult for a kid with small hands to play, and the sound was pretty iffy. The first decent guitar I ever owned, though, was back in the ’50s, when I had my first rock band. It was a Gibson archtop that I used before I switched over to a custom-made Gretsch.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“Nowadays, my main guitar is a limited-edition southern rock version of a Les Paul.”

Taking early inspiration from country music stars like Ernest Tubb, Bill Monroe, Roy Acuff and the Grand Ole Opry radio broadcasts, Daniels had his first solo success in 1973 with his debut single “Uneasy Rider,” a hilarious tale of a hippie whose car breaks down in front of a redneck bar. After forming the first incarnation of the Charlie Daniels Band the following year, the group hit pay dirt in 1979 with the million-selling Grammy-winning single “The Devil Went Down to Georgia,” and the accompanying triple-Platinum Million Mile Reflections album.

Overnight, the band went from playing theaters to performing in arenas. Their varied repertoire would eventually include the songs “The South’s Gonna Do It (Again),” “Long-Haired Country Boy,” The Legend of Wooley Swamp,” “Simple Man” and “In America.” But Daniels gratefully acknowledges Bob Dylan for getting the ball rolling. “Dylan was very generous by listing musician credits on those albums I played on when I was still basically unknown, which really raised my profile to a lot of people.”

When did you first become aware of Bob Dylan?

The first thing that really hit me was “Like a Rolling Stone,” which started charting big in ’65, and then the album Highway 61 Revisited, which was produced by Bob Johnston. I was really taken with Dylan because of his uniqueness. He opened up a lot of doors for me, not that I thought I could ever write like Bob Dylan, because nobody else can.

It was the inspiration I got from his freedom that he basically introduced to the record business. You could express your own individual ideas, even if it took you five or even 10 minutes to do it, rather than, say, three minutes and 40 seconds, which was the way singles were released then. You could put words together any way you wanted to, and if it didn’t make sense to anybody but you, that was all right. He had no boundaries to jump across. He had no envelopes to push, and he’s still doing things his way.

He had no boundaries to jump across. He had no envelopes to push, and he’s still doing things his way.”

— Charlie Daniels

How did you happen to move your whole life to Nashville?

It was back in 1967 when Bob Johnston took the place of Don Law, who was a legendary A&R man at Columbia Records who’d worked with a lot of great artists, like Johnny Cash, and who was retiring at the time. I’d always wanted to live there, so I made the move, and Bob started getting me session work.

Before you actually met Dylan, did you have any pre-conceived notions of what he was going to be like?

Personally, I had no watermark to go by, but the press had portrayed him as this reclusive genius. I can’t speak for Dylan, but I think after his [July 29, 1966] motorcycle accident, when he was holed up in Woodstock for a year, he didn’t want to be pestered by the press the way he was before, when it seemed like everyone wanted to interview Bob Dylan.

Did you have a chance to meet Dylan before the first recording session?

Yes, because Bob Johnston had already been his regular producer for a few years by then. They both came into town a little earlier, so I had a chance to hang out with both of them and got to know Dylan a little bit before going into the studio with him. All I can say is that from that very first meeting, he couldn’t have been any nicer.

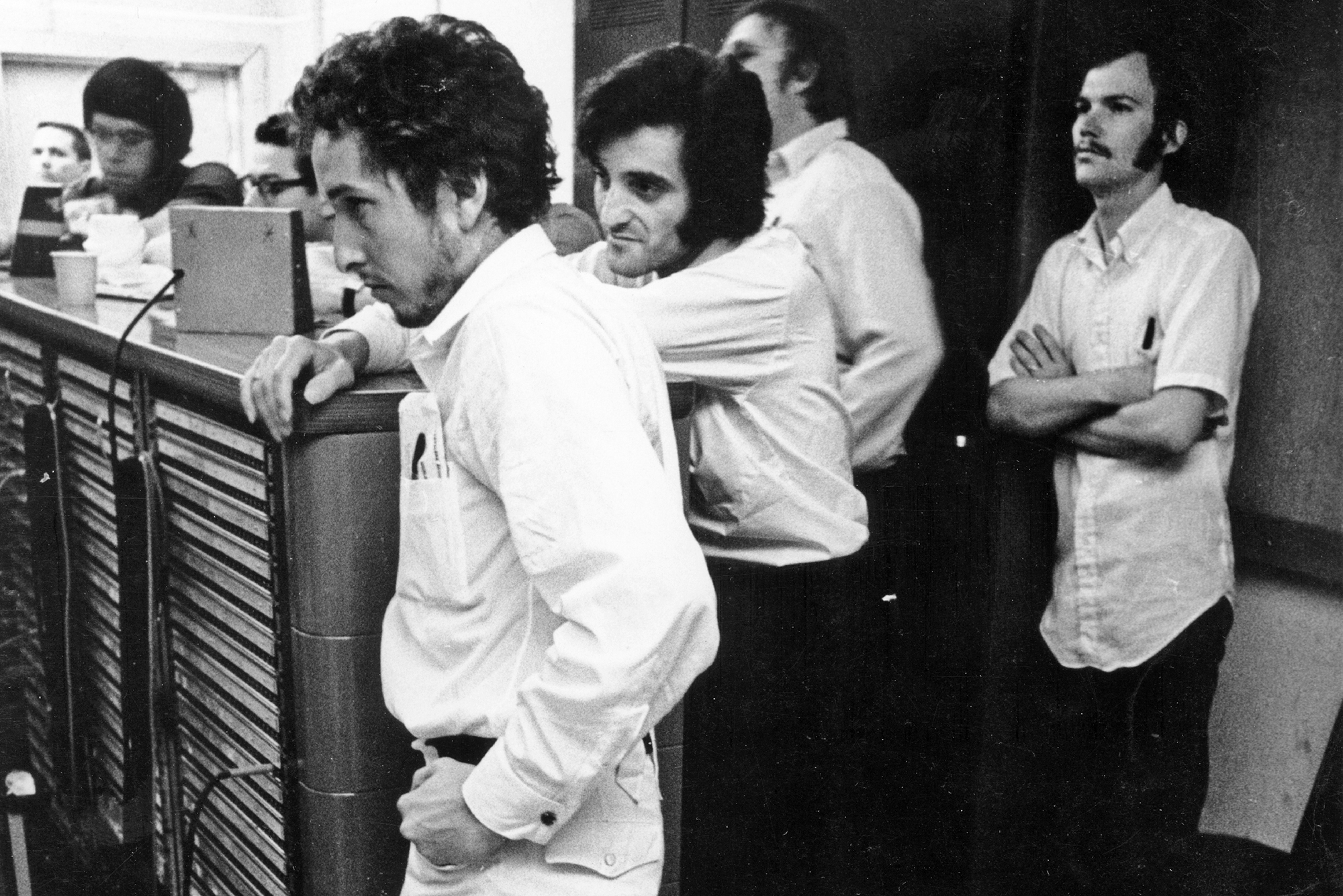

While sitting in with Dylan and the other musicians for the first time to record, were you feeling nervous and intimidated, knowing that these guys were Nashville’s A-team?

Not at all, because I’d actually worked with some of those guys before. I was totally comfortable, and you know what? They turned out to be some of the most relaxing recording sessions I’ve ever been a part of. There was nothing uptight about it. I mean, I didn’t know what to expect, or what kind of sessions Dylan did, or favored. Whatever it was going to be, I was ready for it.

What do you think you did that impressed Dylan so much that he invited you to stay after the first song?

I knew I was honored to be there, so I made sure I was going to do the very best I knew how to do. I was really into everything Dylan was doing. Every single note that he sang. Every single note he played on his guitar I tried to interpret as best I could, and it worked. Everything was incredibly relaxed. Nothing pushy. There was no, “Do this. Do that. Let’s do that guitar solo over.” It was more, “Hey, what you played on that last song, that was really good!”

It sounds like there was more camaraderie among the musicians than competitiveness.

Exactly. That’s what made it all work. One of the great things was that Dylan left you to do what you felt you did best, and that to me, as far as Nashville Skyline was concerned, was one of the greatest charms of that album. It was pretty much, “Here is the song. Here are the chords.” You just played it through a couple of times and everyone jumped on it and left it up to you to create a part that would work. Everything was very straight-ahead, very music oriented.

What’s the story behind “Nashville Skyline Rag”?

It sounds like all the musicians were really having a blast. Well, Dylan played the acoustic lead guitar on one take. Let’s see, [guitarist] Norman Blake was there. I think Dylan played one take on piano. I played one on the electric guitar. It was just something Dylan wrote and wanted to do. He started playing it. Everybody just fell in, and we cut it.

The very first time I heard ‘Lay, Lady, Lay,’ I almost fell on the floor because it was a new chord progression. If I had to pick a favorite, it would have to be ‘Lay, Lady, Lay.’”

— Charlie Daniels

Any special memories of “Country Pie”?

Mainly coming up with my chicken-pickin’ guitar part that I played on my new Telecaster. The first couple of times I heard the song, it just seemed like my part would fit in, so I started playing it. Dylan also liked it. It was actually Bob Wilson who started off the song with that genius piano lick that you would think would be totally out of character before I came in with my solo.

It was just obvious that this approach was very different from what most musicians had probably done on previous Dylan sessions. This new thing with a couple of new players and me and Bob was gonna work. It was going to be something that he liked and that very much fit the song. So, yes, I remember being very pleased with the guitar part I’d come up with.

Of the nine tracks on Nashville Skyline that you played on, do you have a particular favorite?

I do. The very first time I heard “Lay, Lady, Lay,” I almost fell on the floor because it was a new chord progression. Now it’s been used a lot, but at that particular time I had never heard that arrangement of chords put together in that way. It just floored me. I like the whole album, but if I had to pick a favorite that really blew me away, it would have to be “Lay, Lady, Lay.”

On “Lay, Lady, Lay,” he sounded like he was actually singing to a woman, like it was his love song to her. I mean, there’s a lot of love in that song and a lot of emotion, at least to me. I don’t know if I can describe it any better than that. I don’t think anybody else can describe the way Dylan feels about his own music, but yes, I agree, the song was a real departure for him.

On Nashville Skyline, were the instruments and vocals recorded live in the studio?

There might have been some over-dubbing, but Bob Johnston went to great lengths to minimize any leakage while we were recording. I remember they had the most awful-looking apparatus with foam rubber and tape set up between Dylan’s guitar and where the vocal mic was so they wouldn’t have any trouble recording his guitar and his voice together.

How many sessions did it take for all of the recording to get wrapped up?

Actually, 15 sessions were booked, but we wrapped everything up in about eight or nine of them. We did get paid for all of them though.

Fifty years later, what is your fondest recollection of the album?

It really evokes pretty nice memories of the times I spent working with all of those great people on it. Everyone just playing music and having a great time. I still consider it my all-time favorite Dylan album, and not just because I played on it, or for personal reasons. I like every song on it, the arrangements and just everything about it. All I can say is that working with Dylan was not only a very pleasant experience, it was all straight-forward, very laid back, and really a lot of fun.

He was playing all the wrong chords: I felt kind-of funny telling that to Bob Dylan, but he just said, ‘Can you teach them to me?’”

— Charlie Daniels

When you worked with Dylan again on Self Portrait, was it hard to replicate the vibe of the Nashville Skyline sessions?

Well, it was really a very different kind of thing, but it was still a great vibe. I remember when we were recording the old Everly Brothers hit “Let It Be Me,” and he was playing all the wrong chords: I felt kind-of funny telling that to Bob Dylan, but he just said, “Can you teach them to me?” [laughs] Thinking about it now, I don’t think there was anything unusual about it.

In May 1970, during the New Morning sessions, you, Dylan, George Harrison and drummer Russ Kunkel were involved in a mammoth 10-hour session. How did that come about?

Well, I’d just come to New York with Bob Johnston, who was working for CBS at the time, and he invited me along for some company. We were actually on our way to join up with a Leonard Cohen tour in Amsterdam that I was going to be a part of. So anyway, I’m in my hotel room when Bob calls and says, “Would you like to come down to the studio to play bass with George Harrison, Dylan and Russ Kunkel?”

I said, “Well, sure!” It was a very relaxed day. There was nothing particularly planned. Someone would holler out something like, “Hey, Bob, play ‘Gates of Eden,’ and he would sing as much as he could remember, because it was an old song of his.

It was a highly, highly unusual day, and one I wouldn’t trade for anything. It was a truly memorable experience. [Many songs from the session, including “Ghost Riders in the Sky,” “Yesterday,” “All I Have to Do Is Dream” and “Da Doo Ron Ron,” have been heavily bootlegged. Only a few have been officially released, including “If Not For You,” which appears on The Bootleg Series Volumes 1–3 (Rare & Unreleased) 1961–1991.]

What was it like playing with George Harrison?

I loved it. He was a real sweet guy. You know, sometimes you get around some people who are that famous, and there’s not too much to like, but not with George. I mean, the Beatles, of course, are legendary, and George himself was legendary, but he was just like someone you’d known for a long time, and that’s just really the way we all interacted as musicians.

I understand George actually made you a very special employment offer.

Oh, I know exactly what you’re talking about. [laughs] It was actually kind of funny. Paul had just announced to the press that he was leaving the Beatles. As a joking sort of thing, George turns to me and says, in that famous British voice, “Charlie, would you like to be a Beatle…to play bass?” It was a total joke of course, but it was just that kind of session where everybody there was just totally relaxed.

I’m sure you’re familiar with a song George Jones recorded, called “Who’s Gonna Fill Their Shoes?” about some of the musical greats we’ve lost and others we probably will in the near future. So who someday is going to fill the shoes of Charlie Daniels and Bob Dylan?

Those are two pretty iconic names. Well first off, I don’t look at myself as being iconic in the way Bob Dylan is. I wouldn’t put myself in that category. I appreciate if other people think of me that way, but I don’t feel like I’m going to leave a hole in the water that nobody else can close up. If I’ve been a tributary into the river of whatever American music is, and if some people consider me an influence on it, or if they want to build on what I’ve started, then I’m very humbled by that.