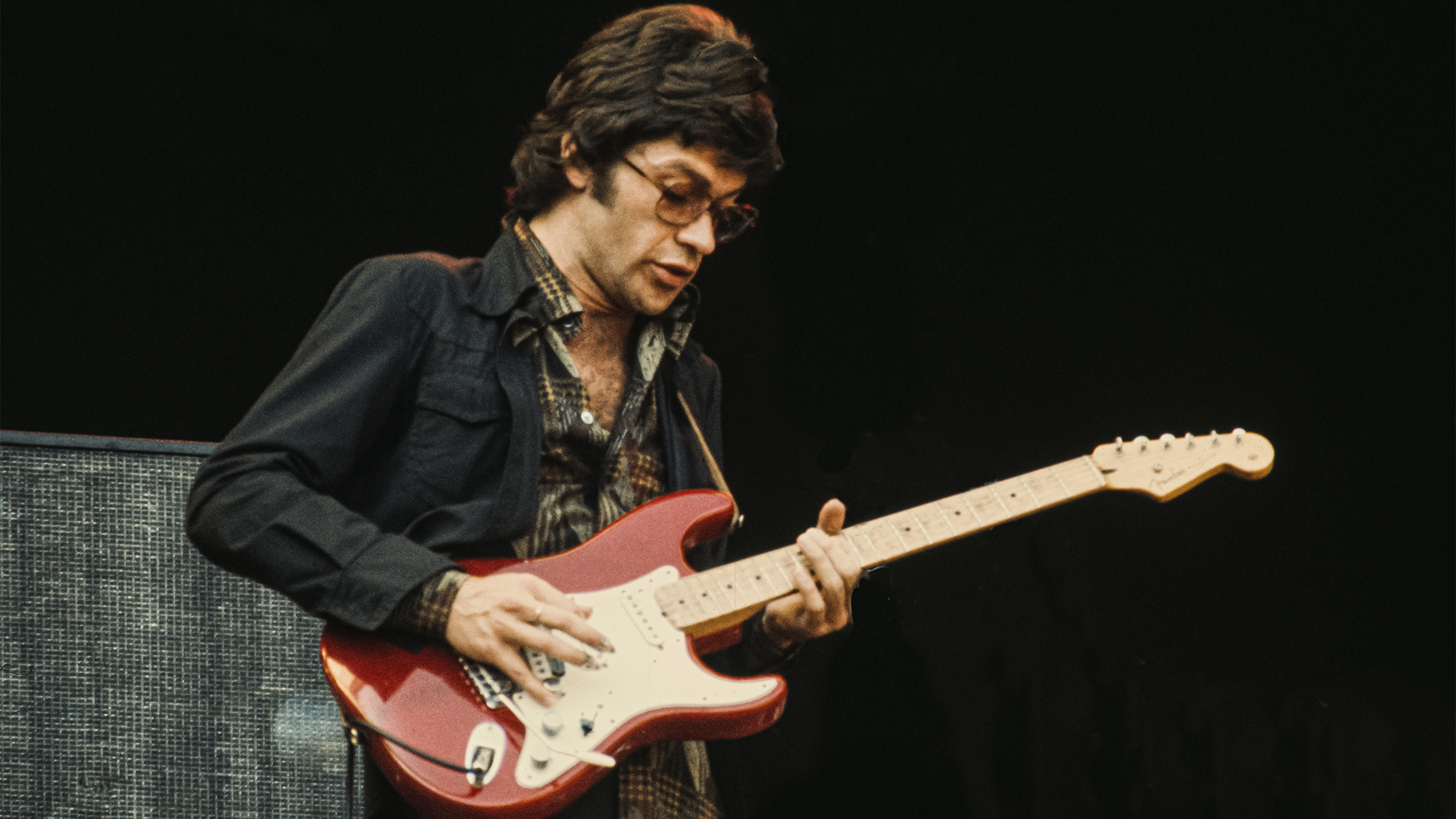

“I was still in this wailing mode. I was a kid on a mission.” Robbie Robertson on Eric Clapton, the power of subtlety and his ‘Last Waltz’ bronzed Stratocaster

The late guitar giant reflected on the power of saying more by playing less

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

“Guitars have their own character, their own identity,” Robbie Robertson once told us. He was sitting at the legendary Village Recorders studio in Los Angeles, in a room filled with his instruments. “They all do different things; they sound different and feel different. You use them in the same way that golfers use golf clubs…or something.”

He laughed. “Actually, I’ve never used that analogy before.”

If you wanted to run with the golf club analogy, you could say that Robertson — a guitarist, songwriter and film composer, and the former co-leader of the Band — was more of an iron man than a wood man.

From the Band’s landmark 1968 debut, Music From Big Pink — with its Americana classic “The Weight” — to Sinematic, his sixth and final solo album, Robertson’s musical game plan was consistently about well-considered short strokes rather than fairway-clearing drives.

When Music From Big Pink emerged at the baroque height of the psychedelic era, the subtlety of his work both as a guitarist and a songwriter was nothing less than revelatory, and it caused countless contemporaries — including Eric Clapton and George Harrison — to immediately reconsider their approach to music.

“When you’re young, you tend to overplay a little bit,” Robertson reflected. “So when I was in the Hawks” — the precursor to the Band — “and we did our first tours with Bob Dylan, I was still in this wailing mode. I was a kid on a mission.

“But by the time the Band made Music From Big Pink, I was leaning in the completely opposite direction; it was all about the subtleties. I was just in such admiration of how Miles Davis would play one note and it would be more effective than somebody else playing 20 notes. And I admired Curtis Mayfield, and Steve Cropper on those Otis Redding songs.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“That kind of guitar playing became very appealing to me,” he continued. “It was all about leaning on the songs, with very little in regard to jamming or playing solos just to put a solo in. And that was like going in the opposite direction [of music] at the time.

“But that’s when people like Eric Clapton heard us and said, ‘That’s the business! That’s what to do!’ At the time, it did have an effect on people, and I kept searching in that mode for things ever since. Not trying to be different but avoiding the obvious and embracing the unexpected.”

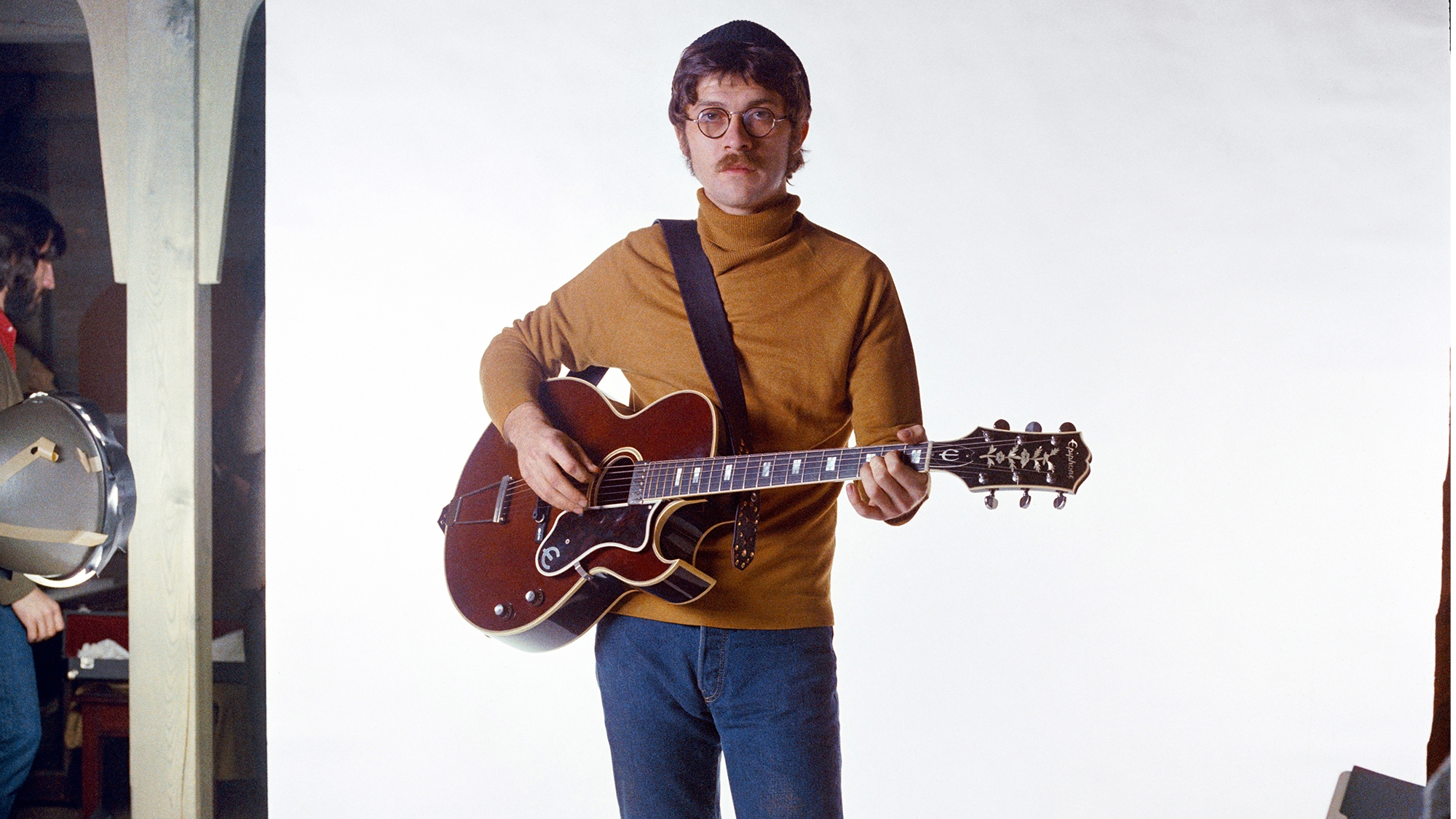

Robertson and Clapton would work together in their careers, most famously at the Band’s Last Waltz concert, where Clapton and the group performed “Further On Up the Road,” and again on Robertson’s 2011 album, How to Become Clairvoyant.

Robertson was joined on that album by numerous guests, including Steve Winwood, Tom Morello of Rage Against the Machine, Trent Reznor of Nine Inch Nails, and funk/soul pedal-steel whiz Robert Randolph.

But it was Clapton who made the biggest contribution, perhaps repaying his musical debt from 43 years before. He penned the album track “Madame X” and co-wrote two others, “Fear of Falling” and “Won’t Be Back.”

Moreover, his enthusiasm for the project — and certainly his guitar playing and choice of instruments — significantly shaped the album.

“Eric has an extraordinary ability,” Robertson noted. “Whoever he’s playing with, he can adjust to that attitude quickly.

“I wanted to avoid acrobatics. When we were recording these tracks, we had it set up so that he and I were just sitting in front of one another, playing together. And when I was playing in this more subtle place, he was playing in a very subtle place.

“All the solos that we did with those tracks were done live. When we would finish singing and doing our subtle things between the lines, and it came to a solo, it was like the guitars were picking up right where the vocals left off. It was like talking guitars — he’d say something and I’d say something, or he’d have a little monologue and I’d answer it with a little monologue.

“There was a particular thing going on, a mature, more grown-up way of us dealing with playing back and forth. It was never like, ‘Oh, I’ll show you something.’”

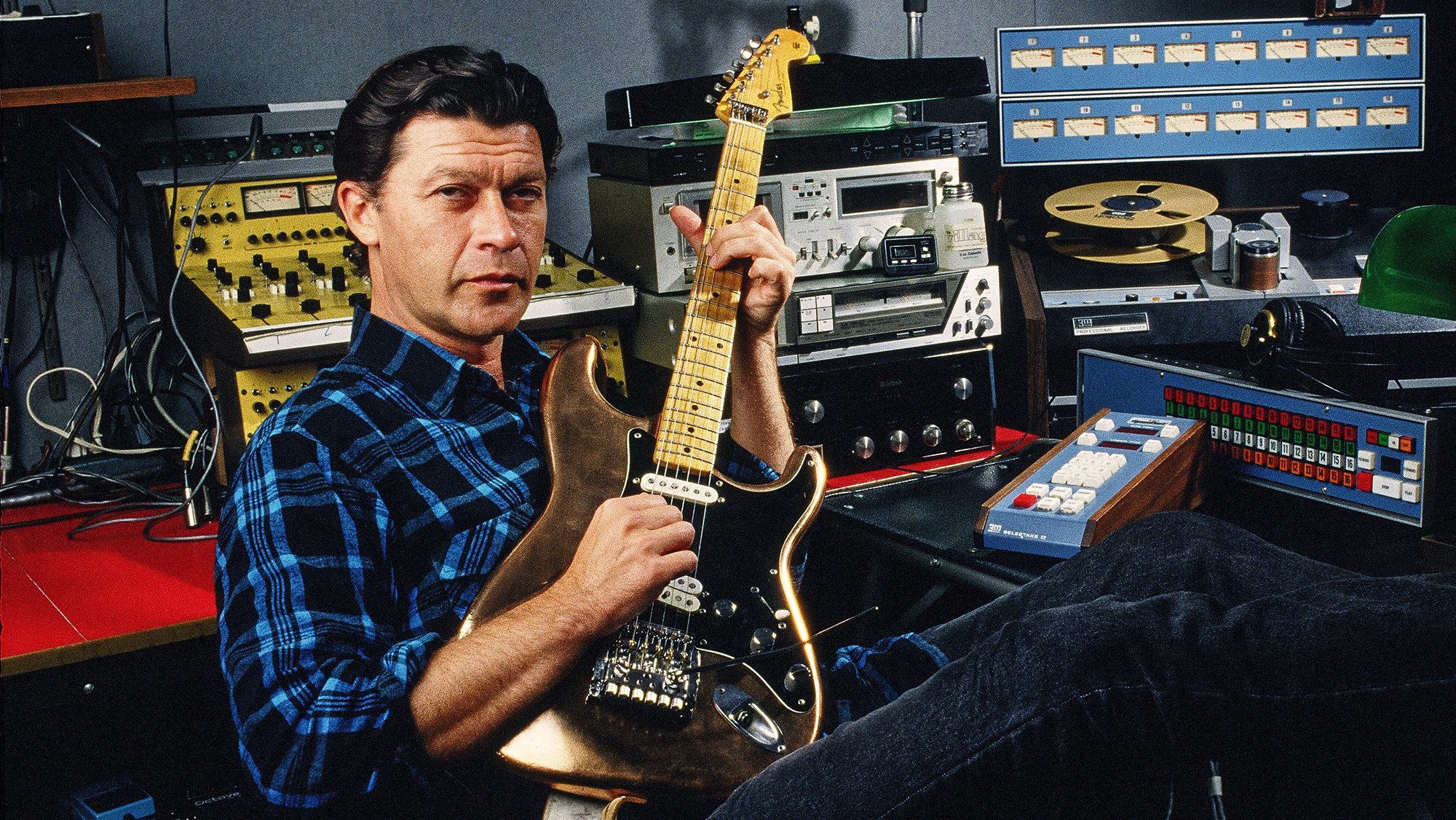

Robertson, however, graciously agreed to show us something: the 1958 Fender Stratocaster he had bronzed for The Last Waltz concert. The most iconic of all of his electric guitars, the bronzed Strat was his main ax for the famed concert.

“The guitar was originally red,” Robertson explained. “I used it on the tour with Bob Dylan in 1974. I used it on Planet Waves, which we recorded with him right before we went on tour, and it’s on Before the Flood, the live album from that tour.

“But when we were preparing to do The Last Waltz, I thought, I should do something for the occasion, and I had it bronzed. They dipped the body in bronze, just like they do with baby shoes. They dip it in, leave it for a minute, and then take it out. So then they put the guitar back together again, and it had a completely different sound to it.”

He laughed.

“Just like you would think, it had a more metallic sound. And I liked the sound I got out of it, but it was heavier. I’m pretty sure I also used the bronzed one on a couple of things on [the Band’s 1977 album] Islands, but after that it was put away.”

Christopher Scapelliti is editor-in-chief of GuitarPlayer.com and the former editor of Guitar Player, the world’s longest-running guitar magazine, founded in 1967. In his extensive career, he has authored in-depth interviews with such guitarists as Pete Townshend, Slash, Billy Corgan, Jack White, Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren, and audio professionals including Beatles engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott. He is the co-author of Guitar Aficionado: The Collections: The Most Famous, Rare, and Valuable Guitars in the World, a founding editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine, and a former editor with Guitar World, Guitar for the Practicing Musician and Maximum Guitar. Apart from guitars, he maintains a collection of more than 30 vintage analog synthesizers.