“He told the story that I got out of the helicopter with a beer in one hand and a tape in the other.” Kris Kristofferson on what really happened when he landed a helicopter in Johnny Cash’s yard to get his demo tape heard

The late singer-songwriter’s stunt would ultimately earn him the opportunity to quit his job and become a full-time musician

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In 1969, Kris Kristofferson was a struggling Nashville songwriter with a license to fly helicopters. Early in the decade, he’d completed Ranger School, one of the military's most physically challenging courses, and received flight instruction at Fort Rucker, Alabama.

For much of the 1960s, he split his time between songwriting and flying. Future hits like “Me and Bobby McGee” and “Help Me Make It Through the Night” were born between gigs flying choppers for a Louisiana petroleum company. Kristofferson probably never imagined his flight skills would come in handy for his music career.

But his separate worlds of music and military training merged one day in 1969 when he got the bright idea to land a helicopter at the Nashville home of Johnny Cash and hand country music’s celebrated outlaw one of his demo tapes. Kristofferson figured the dramatic entrance would impress Cash enough to give his music a listen.

Daring as his act was, Kristofferson wasn’t a stranger to Cash. The country star knew the struggling songwriter as the janitor at Columbia Records, where Cash cut recordings in the 1960s and for much of his career. For that matter, Cash had already received plenty of demos from Kristofferson.

“I’d pitched him every song I ever wrote, so he knew who I was,” Kristofferson said. “But it was still kind of an invasion of privacy that I wouldn’t recommend.”

Military service ran deep in Kristofferson’s family. He was the army brat of an army brat. His grandfather had been an officer in the Royal Swedish Army, and his father would become a major general in the USAF, while his brother went on to become a naval aviator. In 1961, Kristofferson would himself join the Army and, following a tour of duty in West Germany, briefly taught English literature at West Point.

But all along he’d been writing songs. In 1958, Kristofferson was awarded a Rhodes Scholarship and began performing while studying in Oxford. He was signed up by British pop impresario and concert promoter Larry Parnes, who had a stable of young male heartthrob singers with ridiculous names like Billy Fury, Vince Eager and Dickie Pride. In 1960, Parnes would hire the Beatles — unknown and working under the name Silver Beetles — to back his singer Johnny Gentle on a tour of Scotland. Kristofferson cut a few records in England as Kris Carson, but no success came from them.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

But by 1965 he was ready to try again as a songwriter. He resigned from the Army and moved his family to Nashville. He eventually landed the janitor’s job at Columbia Records, placing him in close proximity to artists who might take interest in his songs. It was there he met June Carter and asked her to pass the first of many demo tapes to her husband, Johnny Cash. The country stay probably never listened to it, but he and Kristofferson got to know each other.

To help make ends meet, Kristofferson put his military training to use as a helicopter pilot for Petroleum Helicopters International, in Lafayette, Louisiana.

“That was about the last three years before I started performing, before people started cutting my songs,” he recalled. “I would work a week down [in Lafayette] for PHI, sitting on an oil platform and flying helicopters. Then I’d go back to Nashville at the end of the week and spend a week up there trying to pitch the songs, then come back down and write songs for another week.”

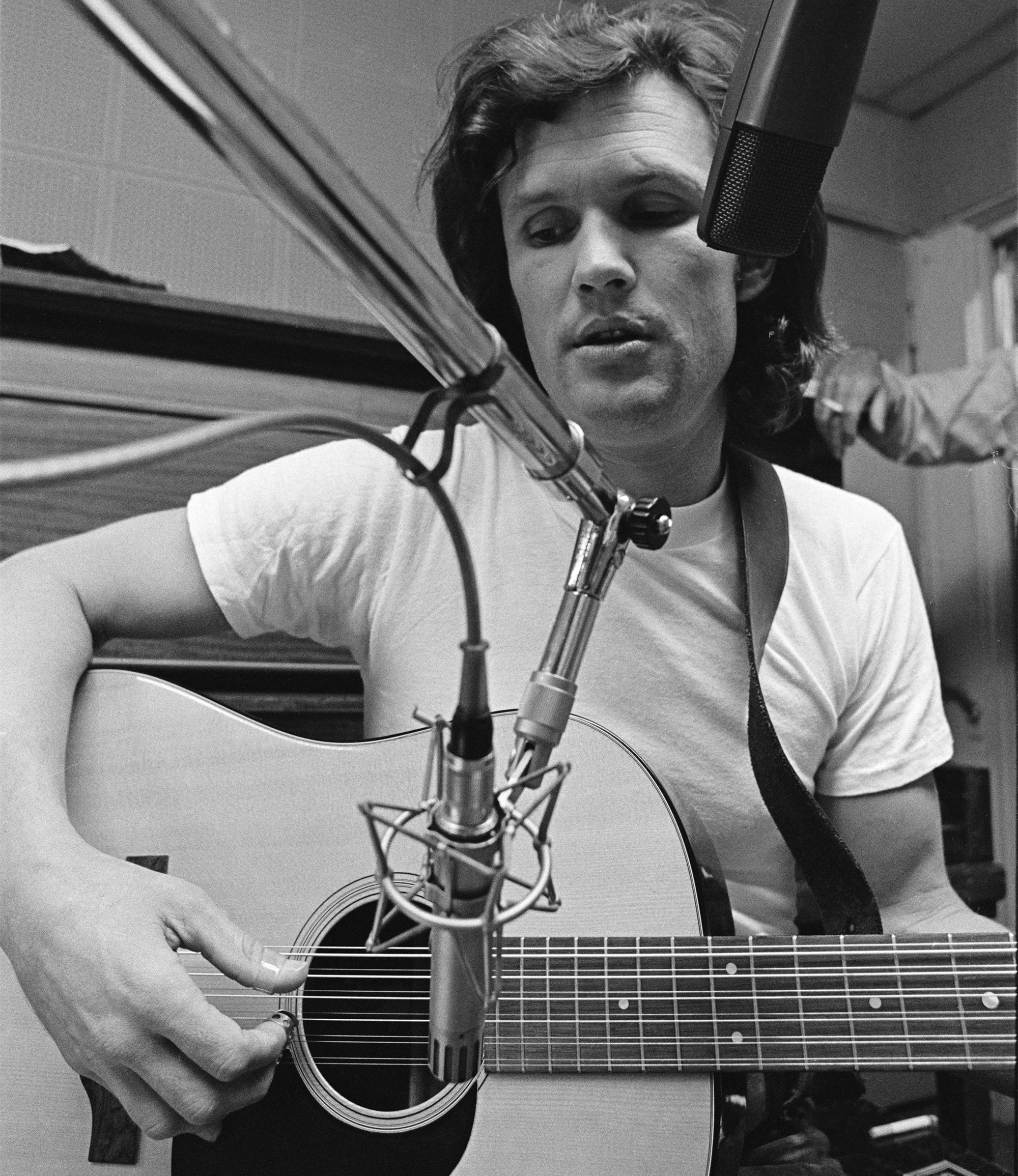

It’s not known what guitar he was playing at the time, but Kristofferson would go on to perform with a Martin D-18 in the 1970s and later played a Gibson SJ Southern Jumbo acoustic.

I can remember ‘Help Me Make It Through the Night’ I wrote sitting on top of an oil platform. I wrote ‘Bobby McGee’ down here, and a lot of them [in Lafayette].”

— Kris Kristofferson

“I can remember ‘Help Me Make It Through the Night’ I wrote sitting on top of an oil platform,” he continued. “I wrote ‘Bobby McGee’ down here, and a lot of them [in Lafayette].”

While other artists, including Roger Miller and Bill Nash, had cut some of Kristofferson's tunes, he couldn’t get Cash to record even one of them. In frustration, he hatched his helicopter caper. The demo he planned to give him was for a new song he’d written. “Sunday Morning Coming Down” was tune about waking up the morning after a binge and facing the cold reality of life.

Kristofferson figured Cash — whose difficulties with alcohol and drugs were well documented in numerous arrest reports — would identify with the humanity at the heart of the composition.

As for the helicopter, some sources say Kristofferson borrowed it from PHI, but the distance of nearly 450 miles between Lafayette and Nashville makes this seem unlikely. Reportedly, he also worked weekends for the Tennessee National Guard, and according to some accounts, including that of Cash, he took the helicopter from there.

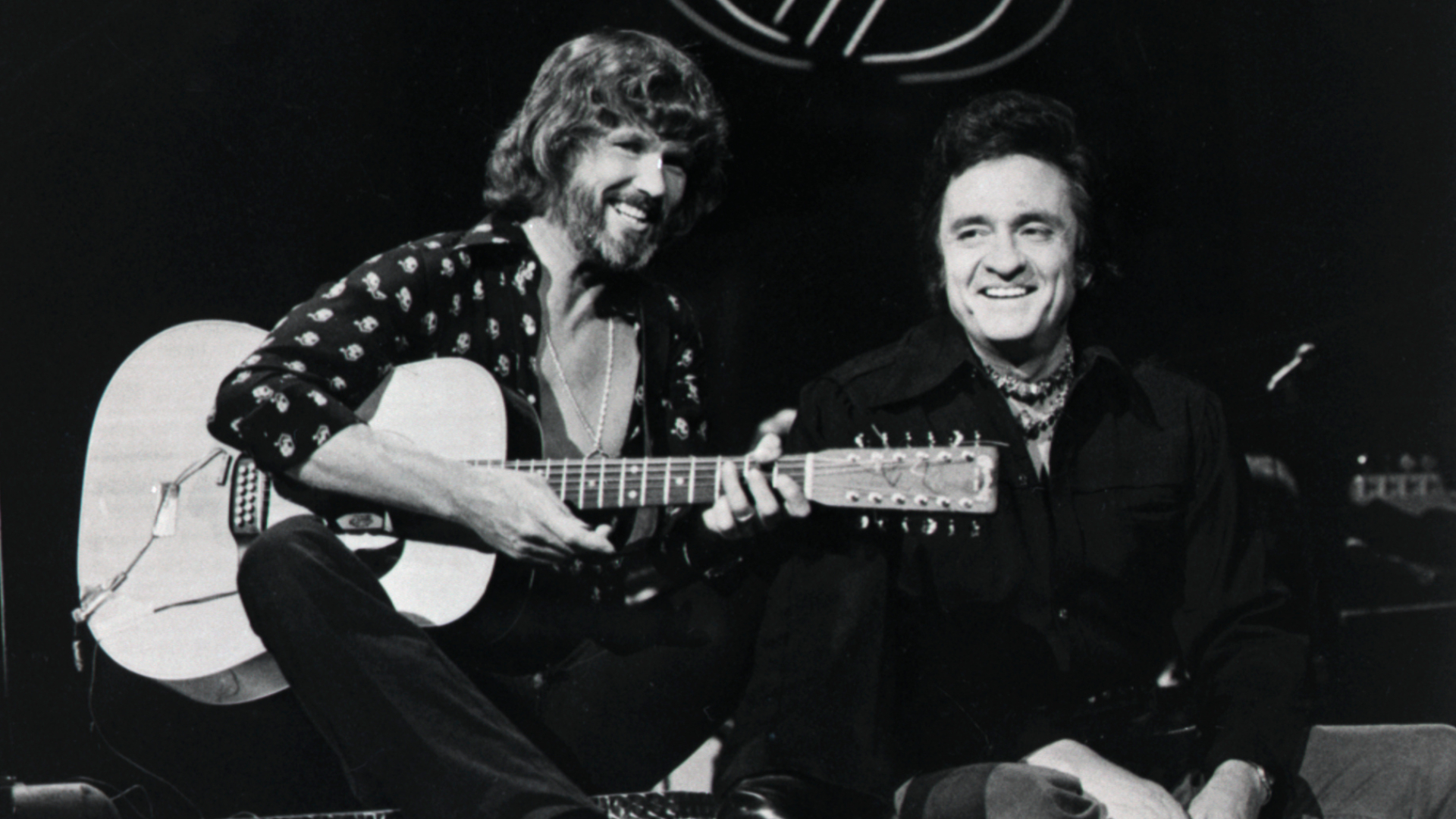

Wherever it came from, Kristofferson followed through with his plan. Johnny Cash recalled the scene in interviews with vivid distortion.

“I didn’t really listen to [the tapes he gave me] until one afternoon, he was flying a National Guard helicopter and he landed in my yard,” Cash recalled. “I was taking a nap and June said, ‘Some fool has landed a helicopter in our yard. They used to come from the road. Now they’re coming from the sky!’

“And I look up, and here comes Kris out of a helicopter with a beer in one hand and a tape in the other.”

June, for her part, said she thought it was the FBI coming for Cash. She’d been worried about a raid on their home ever since customs agents found a stash of amphetamines and sedatives in Johnny’s guitar case in 1965. (Generally a Martin man, Cash also played Gibson acoustics.)

Kristofferson waited until both June and Johnny had passed on before clearing the air about what really happened on that day.

“Well, I admit, that did happen,” he told Cowboys and Indians Magazine in 2011 about his helicopter stunt. “But that didn’t do me any good, landing on John’s property.

“I think he told the story that I got out of the helicopter with a beer in one hand and a tape in the other. But he wasn’t even in the house. And I never would have been drinking while flying a helicopter.”

He wasn’t even in the house. And I never would have been drinking while flying a helicopter.”

— Kris Kristofferson

As for June, “she wasn’t there either,” Kristofferson added with a laugh. “But you know what? I never was going to contradict either one of them.”

Regardless, Cash began to take Kristofferson’s career ambitions seriously and soon after invited him to perform with him at the 1969 Newport Folk Festival.

As for “Sunday Morning Coming Down,” Cash got around to recording it soon after the helicopter stunt. Released as a single in 1970, it went to number one on the Billboard Country chart.

The song’s success "opened up a whole lot of doors for me,” Kristofferson said in a 2013 interview. “So many people that I admired, admired it. Actually, it was the song that allowed me to quit working for a living.”

Christopher Scapelliti is editor-in-chief of GuitarPlayer.com and the former editor of Guitar Player, the world’s longest-running guitar magazine, founded in 1967. In his extensive career, he has authored in-depth interviews with such guitarists as Pete Townshend, Slash, Billy Corgan, Jack White, Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren, and audio professionals including Beatles engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott. He is the co-author of Guitar Aficionado: The Collections: The Most Famous, Rare, and Valuable Guitars in the World, a founding editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine, and a former editor with Guitar World, Guitar for the Practicing Musician and Maximum Guitar. Apart from guitars, he maintains a collection of more than 30 vintage analog synthesizers.