“We used to do a great trick with acoustic guitars.” Paul McCartney reveals three Beatles techniques that explain why they stood out from every other rock and roll band

From performance to recording and arranging, McCartney said the group found ways to make themselves a little different from the competition

An entire branch of literature is devoted to the Beatles and their music, and much of it endeavors to decipher what made the group so wildly successful.

But one thing becomes clear when looking at the group’s innovative approach: Beyond the Beatles’ obvious talent for songwriting and performance, they had a knack for doing things a little differently, enough to make them stand out from the pack and define their own place in rock and roll.

Speaking with Guitar Player for a cover story in the February 1990 issue, McCartney revealed three things the Beatles did to distinguish themselves from the competition. Remarkably, each is a simple deviation from the norm that has a powerful effect on the listener.

From the start, McCartney explains, the Beatles made themselves different by writing their own songs. But just as important, when it came to performing covers, they chose tunes that were below the radar of their audience, giving them a repertoire that differed from other bands, while leaving their listeners uncertain if the songs were originals or not.

“We worked on obscure songs with the Beatles,” McCartney explained. “There was a good reason, too: All the other bands knew the hits; everybody knew ‘Ain’t That a Shame.’ Everybody knew Bo Diddley’s ‘Bo Diddley.’ But not everybody knew [Bo Diddley’s] ‘Crackin’ Up.’ Hardly anybody knows ‘Crackin’ Up’ to this day — it was just one of his B sides that I loved. I don’t know how dynamite it is, but I like it.

“We used to look for B sides — a good, smart move, too! — and obscure album tracks, because if we were turned on by them enough to bring something special to them, just by being in love with them you sing them good. John, for instance, used to sing [Arthur Alexander’s] Anna,’ on the first Beatles album. And that was a really obscure record that we’d just found and [DJs] would play in the clubs.

“We’d take the record home and learn it. We learned a lot of songs like that: [the Coasters’] Three Cool Cats,’ ‘Anna, [the Coasters’] ‘Thumbin’ a Ride’—millions of great songs. And still to this day, I keep them filed in the back of my head in case I’m ever producing a young act, and they say, ‘We haven’t got a song,’ I can go, ‘Wait a minute! Try this one. It’s an old rock and roll thing, but it’s got something.’”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

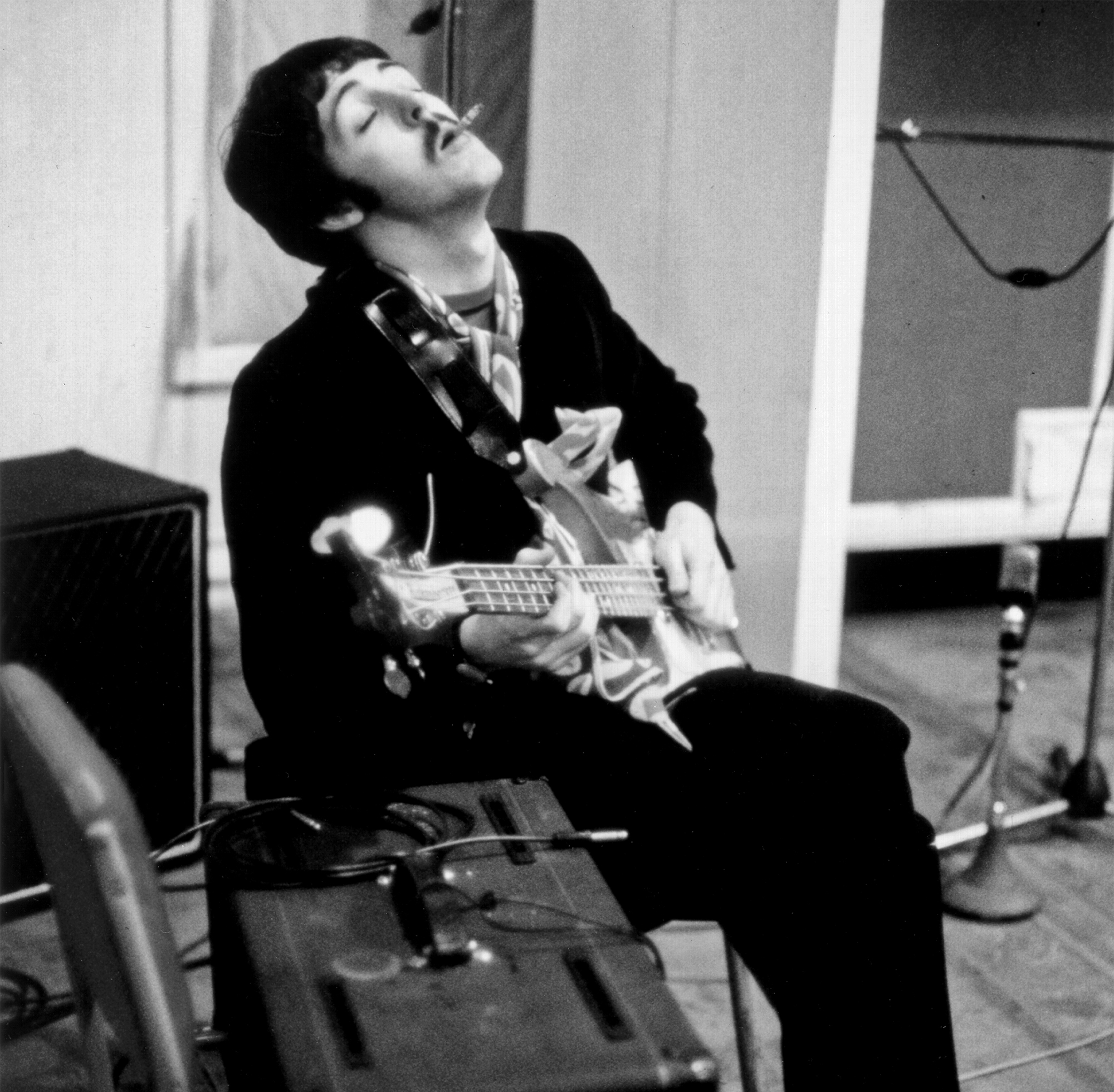

A second trick involves recording. Although the Beatles dutifully followed George Martin’s advice — and the best recording practices of EMI — during their first two years in the studio, by the dawn of 1965 they were eager to shake things up and experiment. This would eventually lead to the innovations heard on later albums, like 1966’s Revolver and 1967’s Sgt. Pepper’s.

As McCartney relates, one of the key advantages of the era were the analog recorders and consoles. Unlike today’s digital technology, analog recording gear could be pushed into overload to produce a satisfying amount of distortion.

It was this exact thing the Beatles learned to do when recording acoustic guitars.

“One of my theories about sound nowadays is that the machines back then were more fuck-upable. I’m not sure if that’s in the dictionary,” McCartney explained. “But they were more destructible. You could actually make a desk [recording console] overload, whereas now they’re all made so that no matter what idiot gets on them, they won’t overload. Most of the old equipment we used, you could get to really surprise you. Now a brand-new desk is built for idiots like us to trample on.

“We used to do a great trick with acoustic guitars, like on ‘Ob La Di, Ob La Da.’ I played acoustic on that, an octave above the bass line. It gave a great sound — like when you have two singers singing in octaves, it really reinforces the bass line.

“We got them to record the acoustic guitars in the red. The recording engineers said, ‘Oh, my God! This is going to be terrible!’ We said, ‘Well, just try it.’ We had heard mistakes that happened before that and said, ‘We love that sound. What’s happening?’ And they said, ‘That’s because it’s in the red.’

“So we recorded slammin’ it in the red. And these old boards would distort just enough and compress and suck. So instead of going [imitates staccato “Ob-La-Di” riff] dink dink dink dink, it just flowed.

“I’m a big fan of blues records and stuff, where there’s never a clean moment. Nothing was ever clean. It was always one old, ropey mike stuck somewhere near the guitar player, and you could hear his foot more than some things.”

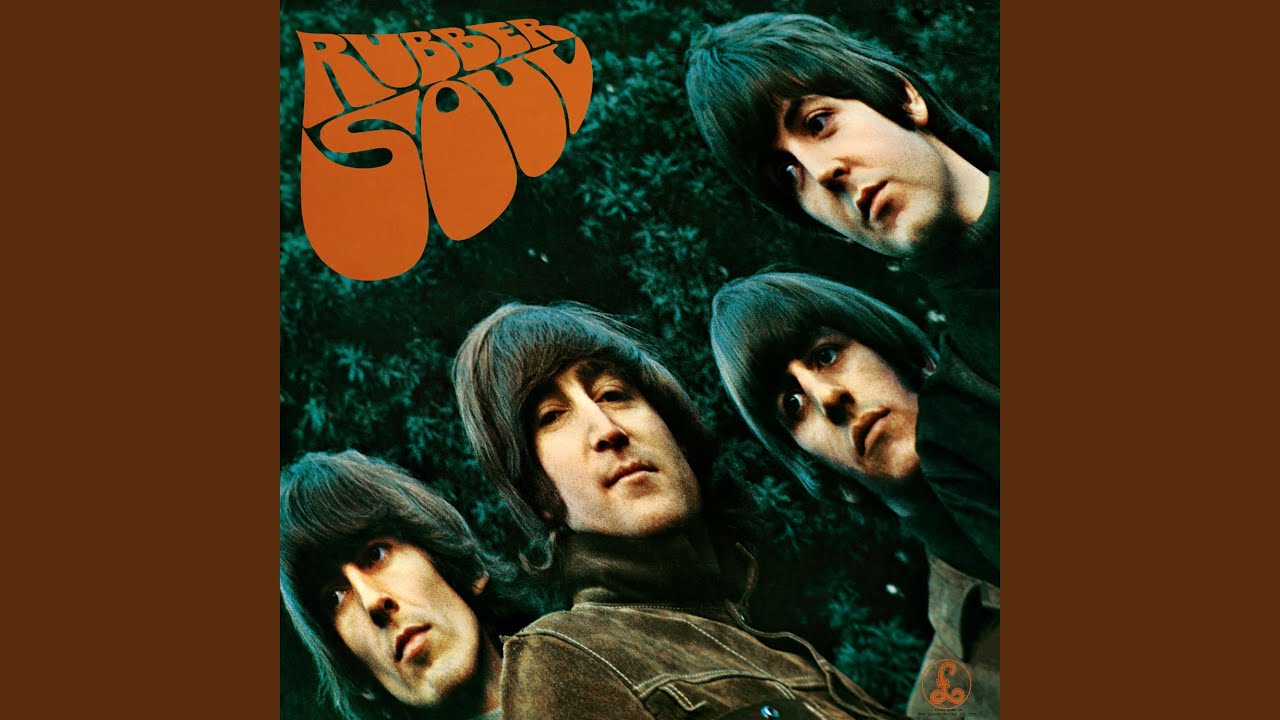

Lastly, as the group’s bass guitar player, McCartney says he learned the power he had to shape the songs just by his choice of bass note. Although on the Beatles’ early recordings he tended to support chords by playing the root, by the time they were recording Rubber Soul in 1965, he had begun to get a handle on creating more theoretically advanced arrangements.

Granted, McCartney was not the first to do this. Motown legend James Jamerson was doing it years earlier, and Who bassist John Entwistle played lead bass like no one else (until Chris Squire came along).

But McCartney made it a signature element in his playing from 1966 forward, no doubt inspired both by Jamerson and from Carol Kaye’s bass playing on the Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds album, also from 1966, performed under the direction of Brian Wilson.

As McCartney noted, he didn’t choose to play bass guitar; he was stuck doing it after Stu Sutcliffe departed the band in July 1961. But soon after, he began to notice the power he had in his new role.

“I didn’t really want to do it, but then I started to see some interesting things in it,” he says. “One of the very earliest was in ‘Michelle’ [from Rubber Soul]. There’s that descending chord thing that goes, [sings bass notes] ‘do do do do words I know do do do do do my Michelle’ — you know, the little descending minor thing.

“And I found that if I played a C, and then went to a G, and then to C, it really turned that phrase around. It gave it a musicality that the descending chords just hadn’t got. It was lovely. And it was one of my first sort of awakenings: ‘Ooh, ooh, bass can really change a track!’

“You know, if you put the bass on the root note, you’ve got a kind of straight track. But later I learned how to make other notes work for me, as Brian Wilson was to prove on the Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds, a big influential album for me. If you’re in C, and you put it on G — something that’s not the root note — it creates a little tension. It’s great. It just [takes a long, expectant, gasping breath] holds the track, and so by the time you go to C, it’s like, ‘Oh, thank God he went to C!’

“And you can create tension with it. I didn’t know that’s what I was doing; it just sounded nice. And that started to get me much more interested in bass. It was no longer a matter of just being this low note in the back of it.”

Christopher Scapelliti is editor-in-chief of GuitarPlayer.com and the former editor of Guitar Player, the world’s longest-running guitar magazine, founded in 1967. In his extensive career, he has authored in-depth interviews with such guitarists as Pete Townshend, Slash, Billy Corgan, Jack White, Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren, and audio professionals including Beatles engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott. He is the co-author of Guitar Aficionado: The Collections: The Most Famous, Rare, and Valuable Guitars in the World, a founding editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine, and a former editor with Guitar World, Guitar for the Practicing Musician and Maximum Guitar. Apart from guitars, he maintains a collection of more than 30 vintage analog synthesizers.