“People always say I’m the Beatle who changed the most.” How playing sitar helped George Harrison become a guitar legend

While the elements of Harrison’s guitar style were falling into place, the Beatles were falling apart. Here’s what happened

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

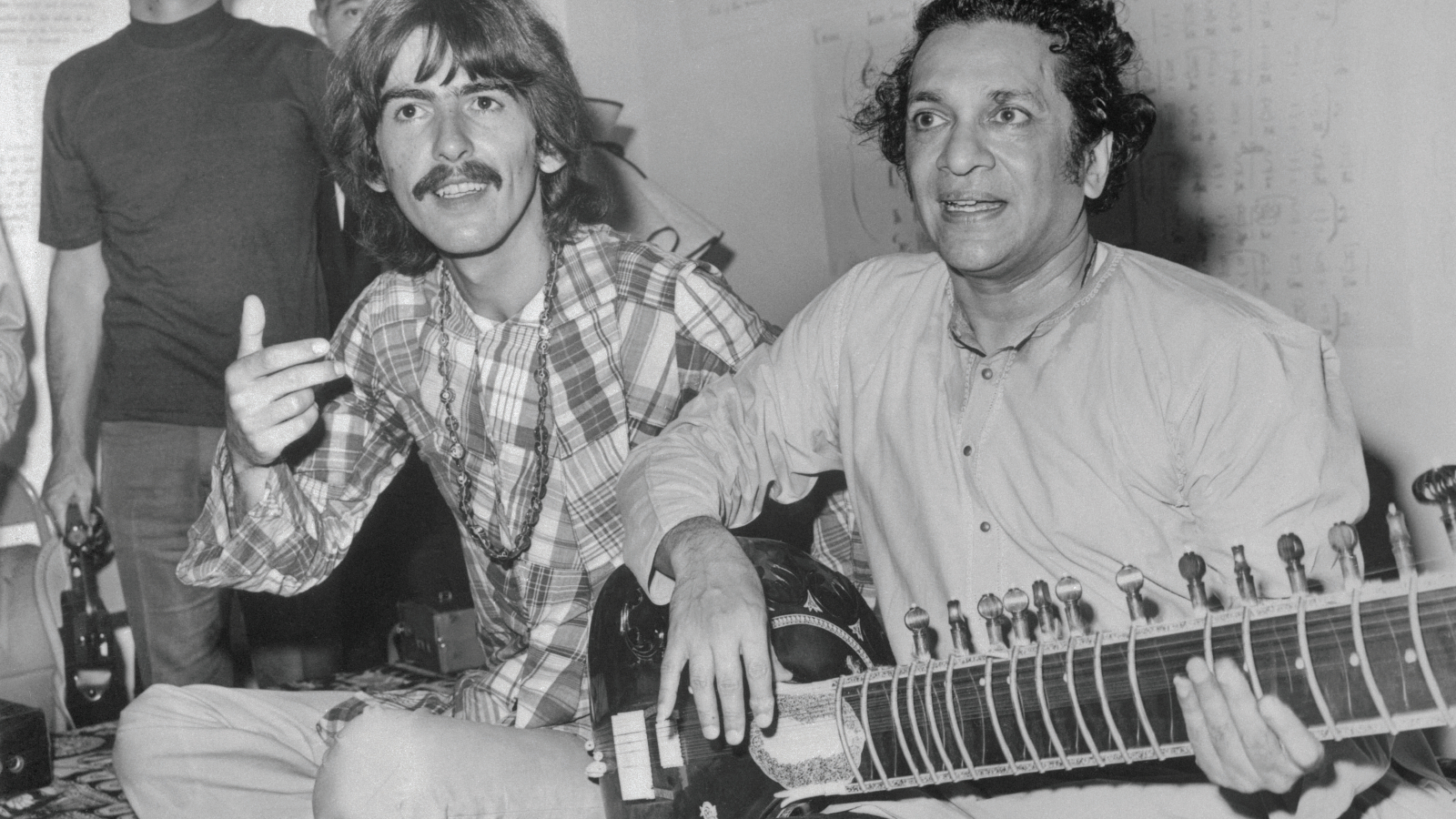

What is a guitarist without a guitar? In September 1966, George Harrison all but gave up playing the instrument when he embarked on a spiritual journey that began with his study of the sitar. With the Beatles just a few months away from recording Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, Harrison traveled to India to begin formal lessons with sitar master Ravi Shankar.

There I am in the paper. It’s funny. It’s just as though it’s a different person

George Harrison, 1963

As he discovered, his education wasn’t performed over a matter of hours-long sessions, nor was it strictly about the sitar. Indian music is inextricably linked with meditation and philosophy. Hindus believe music is God, and the ragas of Indian music are extended hymns to the creator. Studying the sitar is a devotion that takes a lifetime, and which has but one aim: to reveal God.

Far from daunted, Harrison threw himself into his lessons. He was eager to find something for himself, if not of himself. After some three years of global fame as a member of the world’s most popular rock and roll band, he was suffering an identity crisis that had been some time coming.

“You see your pictures and read articles about George Harrison, Ringo Starr, Paul McCartney and John Lennon,” he told a reporter in August 1963, when the Beatles were still unknown in the United States. “But you don’t actually think, Oh, that’s me. There I am in the paper. It’s funny. It’s just as though it’s a different person.”

By 1966, Harrison was known around the world, but his thoughts and ideas were concealed behind the Beatles’ identity. “The funny position I was in was that, in many ways, you know, this whole focus of attention was on the Beatles,” he recalled years later. “So in that respect I was part of it. But from being in them, an attitude came over, which was John and Paul’s.”

Like Lennon and McCartney, Harrison aspired to write songs, and while the few he’d composed were strong enough to stand alongside theirs, his tunes were given less time and consideration by the band and its producer, George Martin. Harrison had even begun to lose his sense of guitar craft. He blamed the band’s constant touring and the hordes of screaming teens at their shows for his inability to develop and improve.

[The sitar] has taken over one hundred percent of my musical life

George Harrison, 1967

But in his studies with Shankar, and eventually with the help of meditation, Harrison found a way to grow not just as a musician but as a person too. The work consumed him. “[The sitar] has taken over one hundred percent of my musical life,” he told Disc and Music Echo in May 1967, eight months after he began his work with Shankar, and just days before the release of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, the album that featured his Indian raga–inspired track “Within You Without You.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“I still love rock, pop and electronic music. But there’s more to get immersed in, for me, in Indian [music]. I shall try to write more songs, and I think it can all be integrated into the Beatles quite nicely if I can keep improving.”

And then, in the summer of 1968, as abruptly as he’d abandoned the guitar, Harrison recommitted to it. He’d even written a song in which the instrument played a central role: “While My Guitar Gently Weeps.” It was one of four Harrison compositions included on The Beatles, the group’s so-called White Album, recorded and released that year.

Unlike many of his contributions from the past two years, the new songs were contemporary rock and roll tunes. Stylistically, however, there was nothing in the Beatles’ catalog quite like them.

Then, the following May, for just the second time, one of Harrison’s songs was selected as a B-side for a single. “Old Brown Shoe” may not have had the pop appeal of the A-side, “The Ballad of John and Yoko,” but it was a rollicking good rock and roll song, full of snarling lead guitar licks and a propulsive bass line played by Harrison himself.

It was impossible not to notice a transformation not only in Harrison’s songwriting but also in his guitar playing

This was but a glimpse of what was to come later that year with the release of Abbey Road, which featured two of Harrison’s best songs: “Something” and “Here Comes the Sun.” “Something” was so good that it was issued as an A-side single. Even Lennon said, “I think it’s about the best track on the album.”

By then it was impossible not to notice a transformation not only in Harrison’s songwriting but also in his guitar playing. More melodic and bluesy than usual, his lead lines were mellifluous, filled with vocal-like bends and moments of sustained beauty as he basked in the spaces between the notes, bending strings and working a sensuous vibrato.

His guitar playing was impeccable, nowhere more so than on drummer Ringo Starr’s Abbey Road song, “Octopus’s Garden,” where Harrison’s lines moved like liquid, imparting the sense of wonder and joy at the heart of the song.

It was clear that a change of some sort had taken place in Harrison. He wasn’t simply a better guitarist or songwriter – he had become stylistically whole.

1970 is indelible as the year George Harrison came into his own as a songwriter and guitarist

Robert Johnson may have allegedly made a deal with the devil in exchange for his guitar talents, but George Harrison had committed to reaching God and become an even finer guitarist than before, not to mention a stronger songwriter and more confident creative artist.

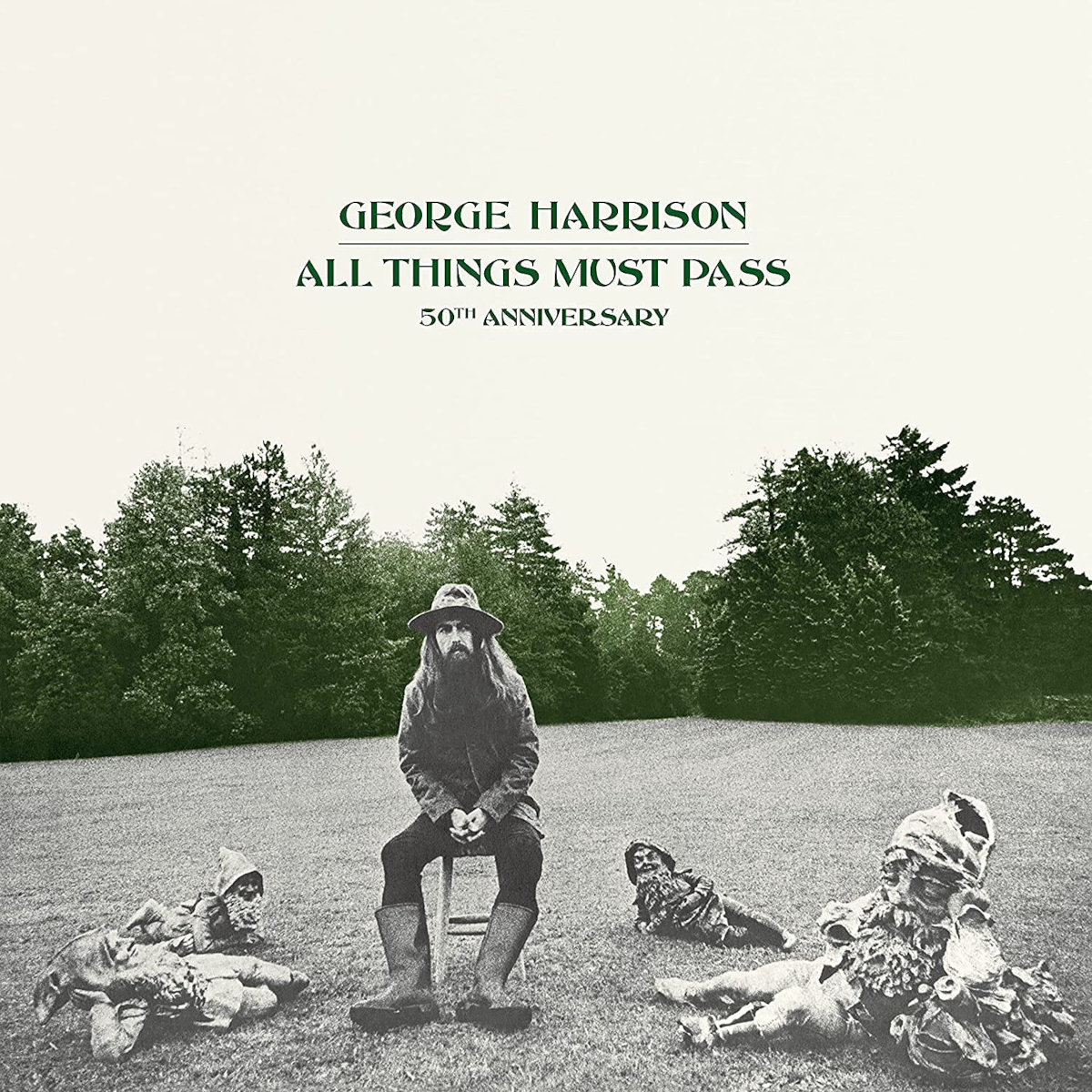

The timing couldn’t have been better. The Beatles were slowly but surely breaking up. Over the next year, Harrison would finally emerge as an independent artist with what many consider to be the finest solo Beatle album, All Things Must Past.

In his remarkable career, 1970 is indelible as the year George Harrison came into his own as a songwriter and guitarist.

RIGHT IN THE MIDDLE

He was known as the Quiet Beatle, but George Harrison always stood out distinctly. As the group’s lead guitarist, he frequently had his brief moment in the spotlight, not the least when the Beatles made their U.S. debut on The Ed Sullivan Show in February 1964.

There may be no more thrilling guitar moments from that first show than Harrison’s confidently fluid solo on “Till There Was You,” delivered with a cocky nonchalance, or his effortless guitar break on “I Saw Her Standing There,” performed while hopping in his boots and smiling at the audience as his fingers danced over the fretboard. His exuberance and charm were in sharp contrast to Lennon and McCartney’s more serious and occasionally clashing temperaments.

He was known as the Quiet Beatle, but George Harrison always stood out distinctly

“He was a catalyst in the band,” recalled Beatles friend, artist and former Manfred Mann bassist Klaus Voormann. “Paul and John were so different, and George was bringing a certain peace into the setup. George was right in the middle between those two characters.”

He was also the moodiest of the foursome. His premiere solo composition, 1963’s “Don’t Bother Me,” was a minor-key surf-beat tune that told the world to keep its distance. The sentiment contrasted sharply with Lennon and McCartney’s love songs, whose first-person point of view made them appear to be direct messages to their female teenage fans.

Harrison could be acerbic (consider his break-up song “Think for Yourself”), indifferent (“If I Needed Someone”) and bitter (“Taxman”). But he could be tender as well, as in his two compositions from 1965’s Help!, “I Need You” and “You Like Me Too Much.”

“George had two incredible personalities,” Starr said. “He had the ‘love, bag of beads’ personality, and the ‘bag of anger.’ He was very black and white.”

He saved the colors and shades for his guitar work. Harrison’s style was a deft fusion of Buddy Holly’s rhythm/lead work, Chuck Berry’s double-stop riffing and Carl Perkins’ sprightly country and rockabilly style, which included chordal arpeggios and single- and double-string bends.

He was clearly an innovator

Eric Clapton

“He was clearly an innovator,” Eric Clapton recalled. “George, to me, was taking certain elements of R&B and rock and rockabilly and creating something unique.”

Harrison’s jazz influences, which included Django Reinhardt, were less obvious but could be overt at times, as on his polished solo for “Till There Was You.”

It was largely through his guitar work that Harrison distinguished himself in the Beatles’ early years. His songwriting contributions were scant, but more than any of the band’s members he lent signature elements to their sound.

During the recording of “Don’t Bother Me” on September 11, 1963, it was Harrison who pushed George Martin, unsuccessfully, to get a different guitar sound using a fuzz box. In the end, they applied tremolo from a Vox AC30 to Lennon’s guitar, probably his 1958 Rickenbacker 325, making this recording, as Andy Babiuk notes in Beatles Gear, “the group’s first evident use in the studio of an electronic effect on the guitar sound.”

On 1965’s “I Need You” and the “Ticket to Ride” B-side “Yes It Is,” Harrison treated his guitar with evocative volume swells, performed with assistance from Lennon. “I could never coordinate it,” he said of his attempts to use an expression pedal, while describing how “John would kneel down in front of me and turn my guitar’s volume control.”

In 1964, Harrison received a prototype of Rickenbacker’s new 360/12 12-string guitar

Remarkably simple and employed just a few times in the Beatles’ extensive catalog (including at the tail end of McCartney’s Revolver track “Here, There and Everywhere”), the effect is nevertheless one of Harrison’s many memorable sonic signatures.

His instrument choices were equally notable. In 1964, Harrison received a prototype of Rickenbacker’s new 360/12 12-string guitar and quickly put it to use on the recording of the single “I Call Your Name” and the group’s third album, A Hard Day’s Night. For the next year and a half, the guitar made appearances throughout the Beatles’ recordings, including on “Ticket to Ride,” from Help!, and Harrison’s Rubber Soul contribution “If I Needed Someone,” where it outlined the song’s signature melody, which was itself inspired by Roger McGuinn’s riff from the Byrds track “The Bells of Rhymney,” also performed on a 360/12.

A PASSAGE TO INDIA

But no instrument was as consequential to the sound of the Beatles’ music, rock and roll, or Harrison’s own development as a musician than the sitar. He had first encountered it on the set of the group’s 1965 film, Help! “There were some Indian musicians in a restaurant scene, and I first messed around with one there,” he recalled.

Harrison felt there was something familiar about Indian music. “It was as if I already knew it,” he said. “When I was a child, we had a crystal radio with long- and shortwave bands, and so it’s possible I might have already heard some Indian classical music.” According to Harrison biographer Joshua Greene, his mother used to listen to the weekly broadcast Radio India when she was pregnant with George, “hoping it would bring peace and calm” to him.

No instrument was as consequential to the sound of the Beatles’ music, rock and roll, or Harrison’s own development as a musician than the sitar

As his curiosity grew, Harrison purchased a sitar from a shop on London’s Oxford Street called Indiacraft. “It was a real crummy-quality one, actually, but I bought it and mucked about with it a bit,” he recalled.

It was summer 1965. That October, the Beatles began the recording sessions for Rubber Soul. Lennon had a new song called “Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)” and was unhappy with how it was coming along.

“We went through many different versions of the song,” he said. “It was never right, and I was getting very angry about it.” The Beatles often turned to unusual sounds when they felt a song was lacking something special. Lennon asked Harrison if he could double his acoustic guitar line on the sitar. “He was willing to have a go, as is his wont,” Lennon said.

The result transformed both the song and popular music.

The following March, the Rolling Stones followed suit by ornamenting their new single “Paint It Black” with a sitar riff written and performed by Brian Jones, who had studied the instrument under Ravi Shankar’s student Harihar Rao. The track became the first rock and roll record with a sitar to hit the top of the charts, and launched a mini craze for the instrument.

The strains of Indian music became even more evident on the Beatles’ next album, 'Revolver'

The increased demand was felt particularly by New York session multi-instrumentalist Vincent Bell, who suddenly found himself hauling his heavy sitar from gig to gig. Worn out by the effort, Bell created a portable electric sitar based on an electric guitar design, which was then developed into a production model under Danelectro’s Coral brand.

Eventually, the sound of his electric sitar was heard on late-’60s hits like the Box Tops’ “Cry Like a Baby,” Stevie Wonder’s “I Was Made to Love Her,” Joe South’s “Games People Play” and many others.

The strains of Indian music became even more evident on the Beatles’ next album, Revolver, where Harrison introduced his first full-fledged sitar track, “Love You To.” Still untrained on the instrument, he applied blues-style licks to it, creating a subgenre of his own somewhere between Delta blues and Indian raga.

The growing influence of Indian music was evident on Paul McCartney’s stinging guitar solo for Harrison’s “Taxman,” a flourish made all the more ironic by the fact that Harrison himself had been unable to muster the performance.

McCartney also lent Indian-style ornamentation to his vocals on the fadeout to Harrison’s “I Want to Tell You,” an element that likewise appeared in Lennon’s backward vocals on “Rain,” recorded during Revolver.

The group had already decided this would be its final tour, and Harrison couldn’t have been happier

Similarly, Lennon’s “Tomorrow Never Knows” was played as a heavy droning raga, as was “And Your Bird Can Sing.” On the latter, over a droning E chord played by Lennon and Harrison on their Epiphone Casinos, Harrison and McCartney performed a baroque lead-guitar harmony, composed by Harrison, that incorporated quick half- and whole-step bends. The result is one part Bach, one part Nashville pedal-steel guitar and one part Indian raga. It provided further evidence of the Eastern influence that was seeping into Harrison’s music.

But it was also a sign of his growing desire for something new. Revolver was, like all of the Beatles’ albums, followed by a tour, but one that proved to be disastrous. They were harassed and threatened in Manila after they unintentionally stood up Philippines First Lady Imelda Marcos. In the United States, they were under attack for Lennon’s remark to London’s Daily Standard that the Beatles were “more popular than Jesus.”

The group had already decided this would be its final tour, and Harrison couldn’t have been happier.

The last stop was at San Francisco’s Candlestick Park on August 29. As the airliner carrying the Beatles’ back to England lifted off from LAX the next evening, he turned to a reporter onboard the plane to cover the group’s tour. “Well, that’s it,” he said flatly. “I’m not a Beatle anymore.”

ROUND TRIP

With no recording sessions scheduled until late November, the Beatles had nearly three months free. Lennon took a role in the satirical pacifist movie How I Won the War, shot in Spain, where he was joined by Starr. McCartney vacationed and scored music for the feature film The Family Way.

Harrison, for his part, left for India to begin his studies with Shankar.

The moment we started, the feelings I got were of his patience, compassion and humility

George Harrison

The two men had first met in London the previous June. “The press had been trying to put me and him together since I used the sitar on ‘Norwegian Wood,’” Harrison recalled. “They started thinking: ‘A photo opportunity – a Beatle with an Indian.’ So they kept trying to put us together, and I said ‘no,’ because I knew I’d meet him under the proper circumstances, which I did. He also came round to my house, and I had a couple of lessons from him on how to sit and hold the sitar.”

Now Shankar welcomed his new student on a houseboat in the Himalayas, where they spent five to eight hours a day in lessons. Harrison found Shankar’s generosity touching, in particular given that he was the world’s most famous sitarist. “The moment we started, the feelings I got were of his patience, compassion and humility,” he said.

“The fact that he could do one of his five-hour concerts, but at the same time he could sit down and teach somebody from scratch the very basics: how to hold the sitar, how to sit in the correct position, how to wear the pick on your finger, how to begin playing. We did that, and he started me going on the scales. And he enjoyed it, he wasn’t grudging at all, and he wasn’t flash about it either.”

Sitting with the sitar for such long periods made Harrison’s hips sore, so Shankar brought in a yoga teacher to teach him exercises. Harrison also began his indoctrination in Indian religion.

“Ravi had a really sweet brother called Raju, who gave me a lot of books by wise men,” Harrison said. He recalled a life-changing passage from one of them, written by Swami Vivekananda, which said, “If there’s a God you must see him, and if there’s a soul we must perceive it. Otherwise it’s better not to believe.”

It was the first feeling I’d ever had of being liberated from being a Beatle or a number

George Harrison

The words were a revelation to Harrison who, as a Catholic, had been raised in the Christian tradition to take God’s existence on faith. “For me, going to India and reading somebody saying, ‘No, you can’t believe anything until you have direct perception of it’ – which was obvious, really – made me think, Wow! Fantastic! At last I’ve found somebody who makes some sense,” he said.

Away from the Beatles, studying sitar and opening his mind to spiritual insights, Harrison was transformed. “It was the first feeling I’d ever had of being liberated from being a Beatle or a number,” he said.

Harrison’s self-discovery was made comically ironic by the fact that Shankar had asked his famous student to conceal his identity. “Ravi Shankar wrote to me before I went out to Bombay, and in the letter said, ‘Try to disguise yourself – couldn’t you grow a moustache?’” Harrison obliged and liked it so much that he wore one for much of his life.

For the next 21 months, Harrison rarely picked up a guitar unless he had to for recording sessions to or compose.

In December 1967, he told an interviewer that he had trouble remembering guitar chord changes, an exaggeration undoubtedly, but also an indication of how deeply he had immersed himself in his sitar studies.

He’d written the Sgt. Pepper’s song “Within You Without You,” as well as the “Lady Madonna” B-side, “The Inner Light,” for Indian instruments. Likewise, other songs from this period, including “It’s All Too Much,” “Only a Northern Song” and “Blue Jay Way,” were composed as droning tunes on the electronic organ, an instrument reminiscent of the harmonium, which is integral to many forms of Indian music.

Harrison had also begun to make a documentary about Shankar, to be released by Apple Films, part of the Beatles’ new Apple Corps multimedia conglomerate. (The movie was issued in 1971 as Raga.)

The first thing that meant something really that I could call a root was riding down the road on my bike and hearing ‘Heartbreak Hotel’ coming out of somebody’s house

George Harrison

In June 1968, he and his teacher trekked out to California to shoot at Big Sur. Shankar had been patient with his student’s sporadic progress, but he also knew the sitar was a daily commitment. In addition to his duties with the Beatles, Harrison was now helping to run Apple and undertaking a film project. Like any good teacher, Shankar tried to guide his student to the right choice.

He made a suggestion that would prove consequential.

“He was the one who said to me, try to find my background, or some root,” Harrison recalled. “What’s my roots? The first thing that meant something really that I could call a root was riding down the road on my bike and hearing ‘Heartbreak Hotel’ coming out of somebody’s house.”

Elvis Presley, not surprisingly, had been a major influence on each of the Beatles, as he had on millions of teens in America, Britain and Europe. “So from there I went from Los Angeles to New York on my way home,” Harrison continued. “That was the last time I really played sitar. I checked in the hotel in New York, [and] Jimi Hendrix and Eric Clapton happened to be staying there.”

Enjoying the familiarity of his fellow guitarists, it seemed to Harrison that he had at last found a place where he fit in, and where he was accepted as an individual, not a Beatle.

“I thought, Well, maybe I’m better off to get back into being a guitar player, songwriter, whatever I’m supposed to be,” he recalled. “Because I’m never gonna be a sitar player. Because I’ve seen a thousand sitar players in India who are twice as better than I’ll ever be!”

A NEW GUITAR

Harrison returned to London and the White Album sessions that summer with a new commitment to his craft. The change in his guitar tone and playing style is evident on several White Album tracks made almost immediately after his epiphany, most notably “Everybody’s Got Something to Hide Except Me and My Monkey” and “Sexy Sadie.” The former song, recorded over June and July, features some of Harrison’s most blues-inflected licks, which serve throughout the track as a second vocal line to Lennon’s own.

Though Harrison viewed Clapton and Hendrix as peers, he had no aspirations to be a guitar hero like them

From this point on, bends and vibrato began to play a more prominent role in Harrison’s guitar playing, and with good reason. The months spent practicing sitar had strengthened his fingers and given him greater control over his instrument.

Coincidentally, in August, Clapton presented Harrison with a guitar that would significantly change his sound: a cherry-red 1957 Gibson Les Paul that Harrison dubbed Lucy. Its fuller, fatter tone gave his guitar playing a more assertive edge on many of the later-recorded White Album tracks, which most likely included “Birthday,” “Helter Skelter,” “Savoy Truffle” and “While My Guitar Gently Weeps,” on which Clapton applied his lead parts using the guitar.

Though Harrison viewed Clapton and Hendrix as peers, he had no aspirations to be a guitar hero like them. He saw himself more in the spirit of Bob Dylan – a songwriter whose lyrics speak to matters of the heart and soul.

Moreover, both he and Clapton were infatuated with the roots-oriented folk-rock of Dylan’s backup group, the Band. Since serving as Dylan’s support in 1965, they’d released their own album, 1968’s Music from Big Pink, recorded in Woodstock, where the five bandmates lived communally, not far from Dylan.

The Band’s earthy mix of acoustic and electric guitars, stripped-down ballads and uptempo songs appealed to Harrison. Certainly, no group from the era had a greater impact on Clapton. Upon hearing Big Pink, he decided to break up Cream and pursue a more blues-based style of music.

In particular, Harrison and Clapton were taken by guitarist Robbie Robertson’s fluid lead playing, which approximated the sound of slide guitar. Unaware that blues guitarists like Muddy Waters used a slide, Robertson had worked for years to develop a vibrato technique that mimicked the effect.

It was an encounter with Dylan that gave Harrison the confidence he needed to assert his songwriting talents to the other Beatles

Harrison and Clapton were also undoubtedly captivated by Big Pink’s opening sound of Robertson’s Telecaster through keyboardist Garth Hudson’s Black Box, a homemade rotary speaker cabinet. Subsequently, Clapton played his Les Paul through a Leslie rotary speaker on “Badge,” the track from Cream’s Goodbye album that he wrote and recorded with Harrison’s assistance. Harrison would also use a Leslie 147RV – a gift from Clapton – on several tracks on Abbey Road and Let It Be.

In the end, it was an encounter with Dylan that gave Harrison the confidence he needed to assert his songwriting talents to the other Beatles.

In November 1968, with the White Album sessions behind him, Harrison accepted an invitation from Dylan to spend Thanksgiving with him and the Band in Woodstock. There in the idyllic wilds of upstate New York, he once again felt the camaraderie he’d experienced meeting Clapton and Hendrix in New York the previous June.

By writing with Dylan, he had achieved something his Dylan-loving bandmates had not

While staying at Dylan’s house, the guitars came out, and soon Harrison’s harmonically inventive chord changes were weaving together with Dylan’s lyrics in a pair of brand-new songs: “I’d Have You Anytime,” which would eventually appear on Harrison’s All Things Must Pass solo debut, and “When Everybody Comes to Town,” which Harrison retitled “Nowhere to Go,” and which has never been officially released.

There in Woodstock, thousands of miles from England, it was not lost on Harrison that, by writing with Dylan, he had achieved something his Dylan-loving bandmates had not.

SONIC SIGNATURE

There was yet one more guitarist who would play an important role in Harrison’s development.

Delaney Bramlett had grown up poor in Pontotoc, Mississippi, and struggled to make a living in his teens, working as a sharecropper before joining the U.S. Navy to escape poverty. He had taken up guitar at age eight and after his discharge settled in Los Angeles, where he got a job in the Shindogs, the house band for the musical variety TV show Shindig!

Harrison’s legacy as a guitarist remains strong, while his music is more popular than ever

The Shindogs’ lineup featured a number of notable and soon-to-be-famous musicians, including guitarist James Burton, pianist Leon Russell, bassist Larry Knechtel and keyboardist Billy Preston. (Preston, for his part, worked with the Beatles during the making of Let It Be in early 1969 and was signed to Apple Records by Harrison, who produced his debut album for the label.)

Outside of the Shindogs, Bramlett had worked with Russell and J.J. Cale and written tunes with Mac Davis and Jackie DeShannon. In 1967, he’d met and married singer Bonnie Lynn O’Farrell.

They joined forces as Delaney & Bonnie and landed a contract with Stax Records, where they released their debut album and established their trademark fusion of soul, gospel and R&B.

Their second album, Accept No Substitute, issued on Elektra the next year, featured an extended band that included Russell, bassist Carl Radle, keyboardist Bobby Whitlock and drummer Jim Keltner, as well as saxophonist Bobby Keys, trumpet player Jim Price and backing vocalist Rita Coolidge.

Harrison met Bramlett in October 1968 while on a visit to Los Angeles to deliver the White Album masters to Capitol and was taken by his easygoing personality and colorful background.

In 1969, the Beatles were on the verge of breaking up, as was Clapton’s post-Cream act, Blind Faith

By the time the Delaney & Bonnie and Friends tour landed on England’s shores in 1969, the Beatles were on the verge of breaking up, as was Clapton’s post-Cream act, Blind Faith. The American troupe joined Blind Faith’s tour as the opening act and soon found their spirited performances earning them greater applause than the headliner.

Clapton was drawn to the group’s music and fun-loving spirit and requested to join them onstage as a guest. By the tour’s end, he was asking if he could be in the band.

Clapton’s participation would set in motion the next stage in his career: Delaney & Bonnie and their backing musicians formed the core of the band on his self-titled 1970 solo debut. Afterward, Clapton would team up with Radle, Whitlock and drummer Jim Gordon, a recent addition to Delaney & Bonnie’s company, to form Derek and the Dominos.

It didn’t take long for Harrison to follow Clapton’s lead. After witnessing Delaney & Bonnie’s December 1 performance at the Royal Albert Hall, he asked Bramlett if he could tag along on the group’s tour. The band picked him up at home the next morning to find Harrison waiting with a gift for Bramlett: a custom Fender Rosewood Telecaster he’d received from the guitar maker at the end of 1968 and used during the making of Let It Be and Abbey Road.

The tour was a fun and relaxing break for Harrison. It was also here that, through Bramlett, he added a new element to his guitar style: slide. Harrison credited Bramlett for instructing him on how to use the device, but as Bramlett told Harrison biographer Simon Leng in his book While My Guitar Gently Weeps, he merely showed Harrison his technique.

Slide guitar soon became a signature element of Harrison’s sound

“One time he asked me if I would teach him how to play slide, and later, George said I’d taught him how to play it,” Bramlett explained. “But I didn’t teach him anything. George already knew how to play guitar; he just wanted to know my technique – what I thought about it and what I did. All I did was teach him my style of playing.”

Whatever the case, slide guitar soon became a signature element of Harrison’s sound. His brief tour with Delaney & Bonnie also provided him with the basic material for his first solo hit, “My Sweet Lord.”

“He said, ‘Say you were going to write a gospel song, how would you start it?’” Bramlett told Leng. Bramlett began scatting “Oh my Lord,” while Rita Coolidge joined in with “Alleluia!”

It was a sound that Harrison, deeply into his spiritual journey, would not forget.

SOLO STARDOM

By the dawn of 1970, all the elements of Harrison’s guitar style were in place. The Beatles, on the other hand, were falling apart.

Though the band hadn’t made their breakup officially known, McCartney was busy working on his solo debut and Lennon was active with his wife, Yoko Ono, on their Plastic Ono Band project, which had briefly included Clapton on guitar.

On January 27, Lennon invited Harrison to participate in the recording of a new song for the group called “Instant Karma!” “John wanted to record it in a day and release it the next day,” Harrison said.

By the dawn of 1970, all the elements of Harrison’s guitar style were in place. The Beatles, on the other hand, were falling apart

Stopping by Apple Corps on his way to the session at Abbey Road Studios, Harrison ran into American record producer Phil Spector, who was in London at the invitation of the Beatles’ new business manager, Allen Klein. Harrison encouraged Spector to come along and oversee the “Instant Karma!” session. It was a fortuitous decision for both men. Noting that McCartney and Lennon were actively pursuing their post-Beatles careers, Spector encouraged Harrison to get busy doing the same.

Until then, Harrison had been more actively involved in other artists’ careers than his own, producing Apple Records signings like Preston and Jackie Lomax, and giving them his songs to record. They included, for Lomax, “Sour Milk Sea,” written in early 1968, and, for Preston, his latest completed effort, “My Sweet Lord.”

Harrison considered Spector’s suggestion, and, shortly after the “Instant Karma!” session, he invited the producer to hear his songs. “I went to George’s Friar Park [estate], which he had just purchased, and he said, ‘I have a few ditties for you to hear,’” Spector recalled. “It was endless! He had literally hundreds of songs… He had all this emotion built up when it released to me. I don’t think he had played them to anybody.”

Harrison’s trove included many songs the Beatles had rejected. Among them were “Isn’t It a Pity,” first offered to the group during the making of Revolver, and numerous tunes from the Beatles’ Let It Be period, including “Let It Down,” “Wah Wah” and, the song that would give his debut solo album its title, “All Things Must Pass.”

In its finished form, All Things Must Pass featured 18 songs – including two versions of “Isn’t It a Pity” and a cover of Dylan’s “If Not for You,” from his 1970 album New Morning – spread over two vinyl albums. The set was supplemented by a third disc, titled Apple Jam, that featured informal workouts recorded with the album’s musicians, including Clapton, Starr, Delaney & Bonnie, and members of their band.

People always say I’m the Beatle who changed the most. But, really, that’s what I see life is about. The whole thing is to change and try to make everything better and better

George Harrison

All Things Must Pass was released on November 27, 1970. In the U.S., Harrison’s debut single, “My Sweet Lord,” was issued a few days earlier to help build excitement for the album. It wasn’t necessary. Beatles fans were eager for new music from their idols, even if they were now solo artists.

All Things Must Pass quickly reached the top of the charts in the U.S., U.K. and many other major markets. In the U.S., the album and the “My Sweet Lord” single simultaneously held the top spots on their respective charts, a feat known as a “Billboard double.”

It would take another year and a half before another Beatle, Paul McCartney, achieved the same.

For the millions who had followed the Beatles, Harrison’s transformation was remarkable. Looking for something to satisfy his soul, he found a way to express himself and, in doing so, become a consummate guitarist and songwriter.

Even today, 50 plus years after the Beatles’ breakup, Harrison’s legacy as a guitarist remains strong, while his music is more popular than ever, with “Something” and “Here Comes the Sun” besting even longtime favorites like “Yesterday” and “Hey Jude” on streaming music charts.

Harrison, who died in 2001, might not be surprised.

“People always say I’m the Beatle who changed the most,” he noted in his later years. “But, really, that’s what I see life is about. The whole thing is to change and try to make everything better and better.”

Order George Harrison’s All Things Must Pass here.

Christopher Scapelliti is editor-in-chief of GuitarPlayer.com and the former editor of Guitar Player, the world’s longest-running guitar magazine, founded in 1967. In his extensive career, he has authored in-depth interviews with such guitarists as Pete Townshend, Slash, Billy Corgan, Jack White, Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren, and audio professionals including Beatles engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott. He is the co-author of Guitar Aficionado: The Collections: The Most Famous, Rare, and Valuable Guitars in the World, a founding editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine, and a former editor with Guitar World, Guitar for the Practicing Musician and Maximum Guitar. Apart from guitars, he maintains a collection of more than 30 vintage analog synthesizers.