“The next person that walks across this stage is gonna get effing killed!” Pete Townshend declared war at Woodstock when Abbie Hoffman interrupted the Who in the middle of their biggest gig

The preeminent festival of peace and love was anything but when one of the era's biggest political activists cut in on one of its most powerful rock acts

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Woodstock is remembered as three days of peace, love and music. But for every person who attended — and for every performer who played — the 1969 festival would come to mean something entirely personal.

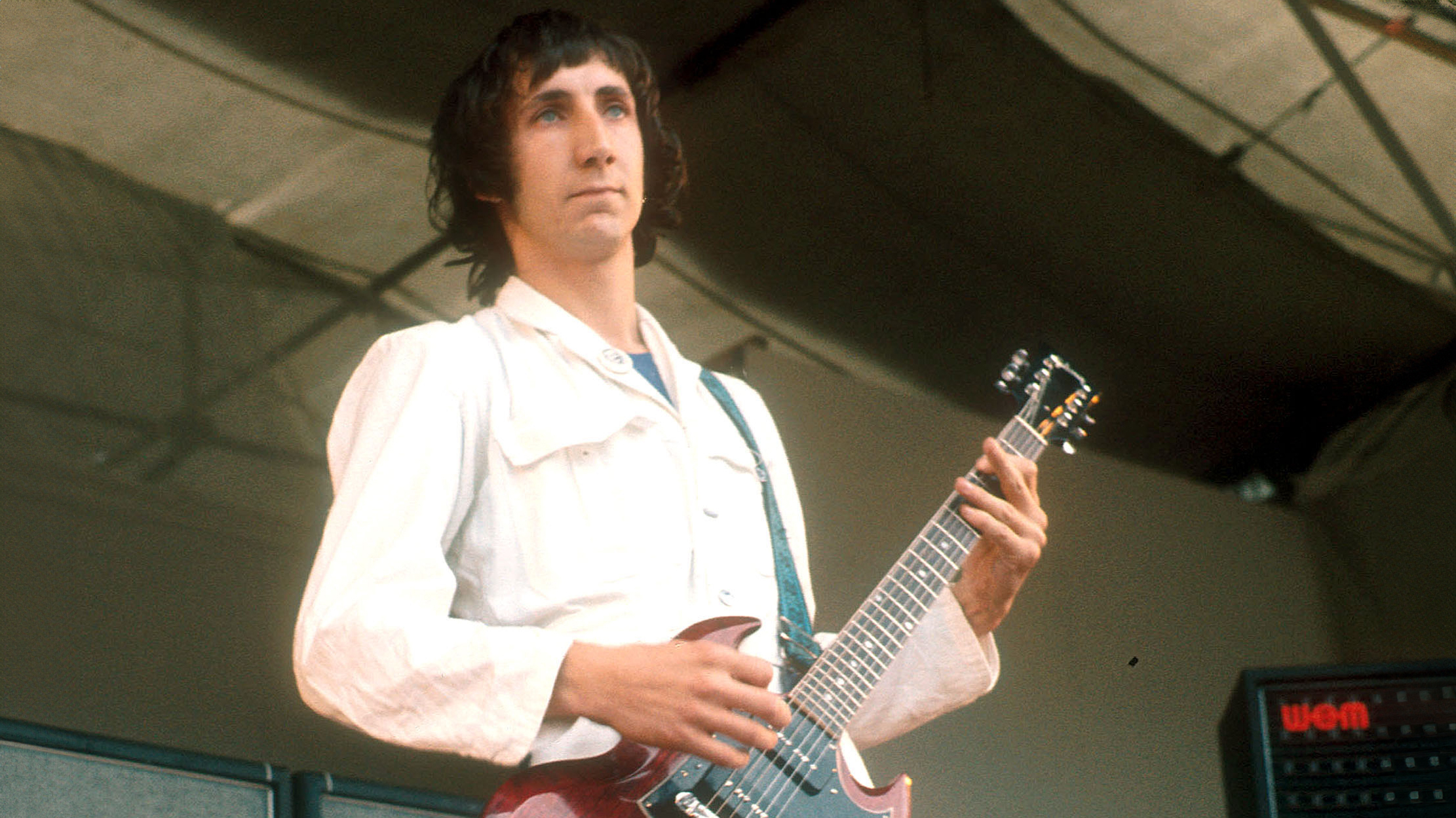

For Who guitarist Pete Townshend, it was a dispiriting tragedy. The group’s set in the early morning hours of August 17 featured a performance of their then-new groundbreaking rock opera, Tommy. It was the Who’s breakthrough album, a smash hit that secured them a place in America some two years after their debut performance at 1967’s Monterey Pop festival, where the Jimi Hendrix Experience had also made their U.S. premiere.

But unlike Monterey Pop, Woodstock looked to Townshend like a disorganized mess. The sight of roughly half a million fans camped out on the muddy fields of Max Yasgur’s farm in Bethel, New York was bad enough. To make it worse, delays caused the Who’s set to move from late Saturday night to five o’clock on Sunday morning, August 17.

Taking the stage, Townshend was dismayed to deliver his rock opera to thousands of stoned and sleeping attendees. The Who should have been celebrating their place as one of rock’s foremost groups. But all Townshend could think was that he was losing his audience.

“I find myself in sort of a class of one having the courage to admit that I hated Woodstock and that it was actually quite horrible to be up to your neck in mud,” he told Guitar Player in the October 1989 issue.

“And in a sense, what people were looking for was just something to hang on to. Tommy actually filled a need. There were people out there with a spiritual hole in their life, which they filled up and partly created by using psychedelic drugs. Everybody was using psychedelic drugs.

“And the people who weren't were using strong hallucinogenics — even though they didn't know it — in the shape of marijuana. You know, where if you took six joints in a row you were in the first stages of a psychedelic experience anyway. And that was just rampant.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“And Woodstock… well, the whole audience was on LSD. It's really quite a grotesque idea that you're actually there with a million mad people.”

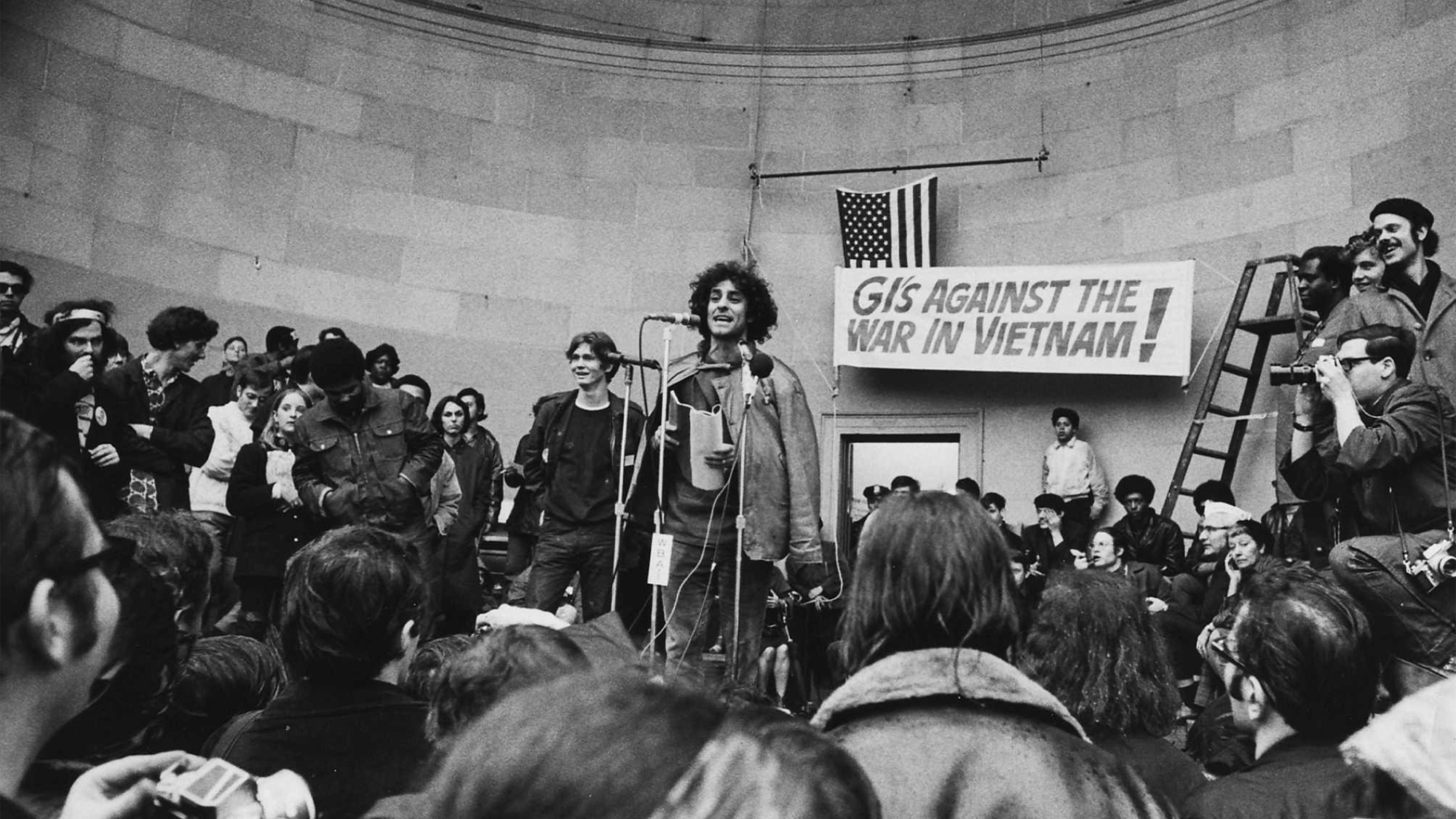

Among them was a man who was, if not “mad,” then truly angry: Abbie Hoffman. One of the 1960s most influential political activists, Hoffman was the founder of the antiwar Youth International Party, whose members were known colloquially as Yippies.

At the time of Woodstock, Hoffman was preparing to stand trial as one of the Chicago Seven, who were charged in 1967 with crimes for activities associated with protests against the Vietnam War. That trial would begin in September 1969.

I find myself in sort of a class of one having the courage to admit that I hated Woodstock and that it was actually quite horrible to be up to your neck in mud.”

— Pete Townshend

But in August 1969, Hoffman was preoccupied with a different trial, that of John Sinclair. A poet from Flint, Michigan who managed the MC5 and founded the militant anti-racism White Panther party, Sinclair was busted for offering two joints to an undercover officer. He was given nine and half to 10 years in prison.

Hoffman and Sinclair were cut from the same cloth politically, and Hoffman was outraged at the harsh punishment his friend had received. Disgusted by the blissed-out hordes at Woodstock, he chose the middle of the Who’s set as the moment to vent his anger.

As the final chord of “Pinball Wizard” rang out, Hoffman ran onstage and commandeered a microphone. Footage of the moment doesn’t exist, but the audio recording captures it in detail:

“I think this is a pile of shit, while John Sinclair rots in prison,” Hoffman sneers.

A chorus of boos cries out from the audience..

Almost immediately, Townshend can be heard responding off mic.

“Fuck off!” He demands.

Hoffman utters something that sounds like “What?” — a response to Townshend, or possibly a continuation of his diatribe. But before he can utter another word, Townshend cuts him off.

“Fuck off my fucking stage!” he roars.

There’s the sound of guitar noise, some fiddling on the bass guitar by John Entwistle, and then deafening cheers from the crowd as Townshend goes after Hoffman, reportedly hitting him in the back with his Gibson SG Special to drive him offstage.

The video returns almost immediately, revealing Townshend, scowling, as he takes his position at the microphone.

I think this is a pile of shit, while John Sinclair rots in prison."

— Abbie Hoffman

“I can dig it,” he says mockingly.

The band continues on, playing Tommy’s “Uncle Ernie,” but Townshend is distracted by his guitar, which is now out of tune following his assault on Hoffman. As the verse ends, he immediately runs his pick down each string to check his tuning before stepping up to the microphone.

“The next fucking person that walks across this stage is gonna get fucking killed,” he announces to cheers and applause.

So much for peace and love.

“You can laugh,” Townshend says, although no one is heard laughing. “I mean it!”

Townshend would later say he had no idea who Hoffman was. Ironically, he not only agreed with him about Sinclair’s imprisonment — he harbored the same feelings about Woodstock’s wasted teens.

In the end, the Who’s set would be seen as one of the festival’s standout performances. Tommy had demonstrated that Townshend was a songwriter and musical innovator, and that the Who were a powerhouse act. But Woodstock proved that they were one of the era’s greatest performing acts.

As a one-two punch, Tommy and Woodstock was an unbeatable combination that made superstars of the group. But all Townshend saw was how the event — both in its size and recreational drug use — was creating a rift between him and his audience.

“What ultimately alienated us from our fans was the way Woodstock turned us into superstars,” he told me in 2000. “In some ways that was wonderful. We went from being a band with a predominantly male following to one where Roger [Daltrey] seemed to be like a new kind of rock sun god. And we had a few women in the audience for a change.

“But in other ways it was disarming, because the actual natural, easy connection between me, as the writer, and the audience was broken.”

It was also at Woodstock that Townshend began to fear the 1960s teen culture revolution had lulled itself — and pop music — into irrelevance.

As the sun rose that Sunday morning, he saw not the 1960s’ promised nirvana but the “teenage wasteland” he would evoke in the Who's 1971 hit “Baba O’Riley.”

“‘Baba O’Riley’ is about the absolute devastation of teenagers at Woodstock,” he said, “where everybody was smacked out on acid and 20 people, or whatever, had brain damage. The contradiction was that it became a celebration: ‘Teenage wasteland! Yes! We’re all wasted!’”

‘Baba O’Riley’ is about the absolute devastation of teenagers at Woodstock. ‘Teenage wasteland! Yes! We’re all wasted!’”

— Pete Townshend

Devastation had influenced Townshend before. Seeing the guitar talents of Jimi Hendrix in 1967 wrecked his confidence and convinced him he was outgunned. In response, he put his focus on songwriting. The result was Tommy.

Now, disillusioned with the wasted youth of Woodstock, Townshend would respond with a new rock opera called Lifehouse, about a populace that whiles its life away in state-assisted slumber. The project would overwhelm him and push him to verge of suicide before he abandoned it.

But from its ashes, he and the Who would create Who’s Next, the 1971 studio follow-up to Tommy that firmly established them as one of rock and roll’s biggest acts and Pete Townshend as one of rock’s most visionary talents.

Christopher Scapelliti is editor-in-chief of GuitarPlayer.com and the former editor of Guitar Player, the world’s longest-running guitar magazine, founded in 1967. In his extensive career, he has authored in-depth interviews with such guitarists as Pete Townshend, Slash, Billy Corgan, Jack White, Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren, and audio professionals including Beatles engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott. He is the co-author of Guitar Aficionado: The Collections: The Most Famous, Rare, and Valuable Guitars in the World, a founding editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine, and a former editor with Guitar World, Guitar for the Practicing Musician and Maximum Guitar. Apart from guitars, he maintains a collection of more than 30 vintage analog synthesizers.