How Pete Townshend Turned the Trauma of His Aborted Sci-fi Rock Opera into the Triumph of 'Who's Next'

In 1971, the Who guitarist was taken to the brink trying to follow the success of 'Tommy.' He came out the other end with a masterpiece.

Standing before an open window on the 24th floor of New York City’s former Navarro Hotel, Pete Townshend fell into the throes of what he calls “a classic, extreme, psychotic, New York anxiety attack.”

It was March 1971, and the Who had come to the city on the recommendation of their manager, Kit Lambert, in a last-ditch effort to record a musical project that had been plaguing the guitarist. Lifehouse, as he called it, was the concept album that would surpass Tommy, the Who’s groundbreaking, 1969 rock opera.

Since 1966, Townshend had been developing the format, first with his nine-minute mini-opera, “A Quick One, While He’s Away,” and then with the musical suite “Rael” on 1967’s The Who Sell Out, an album of songs presented – as an afterthought, Townshend explains – in the guise of a pirate radio station broadcast.

But it was with Tommy that he pulled the essential pieces together: a dramatic story arc and a set of musically ambitious tunes that didn’t neglect the commercial song format.

With its plot about an enigmatic deaf, dumb, and blind boy, and radio hits like “See Me, Feel Me” and “Pinball Wizard,” Tommy was the artistic breakthrough that took the Who to the heights of both critical respect and pop stardom.

Before it, no one in the Who – not Townshend, singer Roger Daltrey, bassist John Entwistle nor drummer Keith Moon – thought the band had the legs to endure a long future. Tommy changed everything. The Who seemed poised to define rock and roll for the brand-new decade. And they would start with Lifehouse, Townshend’s latest rock opera.

There was just one problem: No one could understand the new project’s science fiction–inspired plot or the message at its heart. Kit Lambert was Townshend’s longtime creative support and “interpreter,” the one person who might have been able to help him sort out the project’s complexities. But the manager had dejectedly departed London for New York City in 1970 after the guitarist rejected his script for a film about Tommy.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Longing for a rapprochement with the one person who could help him, Townshend had eagerly accepted Lambert’s invitation to record in New York City. But their reunion was anything but warm. The grandiose plans for Lifehouse were falling apart and taking Townshend with them.

Sitting with his bandmates in the manager’s hotel room, his anxiety reached its peak. “I got this welling of energy, which I think you can only get in New York,” he explained to me some years ago. “And I started to hallucinate. I thought, I must get some air, and I stumbled toward the window.”

Whether he was momentarily oblivious to his predicament or intent upon ending it all, Townshend wouldn’t say. Either way, the consequences would have been fatal. “I was about to jump out when Kit’s secretary grabbed me – just like that!” he said. “I nearly killed myself.”

Fifty years have passed since that consequential day, and fans are still waiting for the full presentation of Lifehouse. But the album they received in its place in 1971 certainly bore no evidence of compromise.

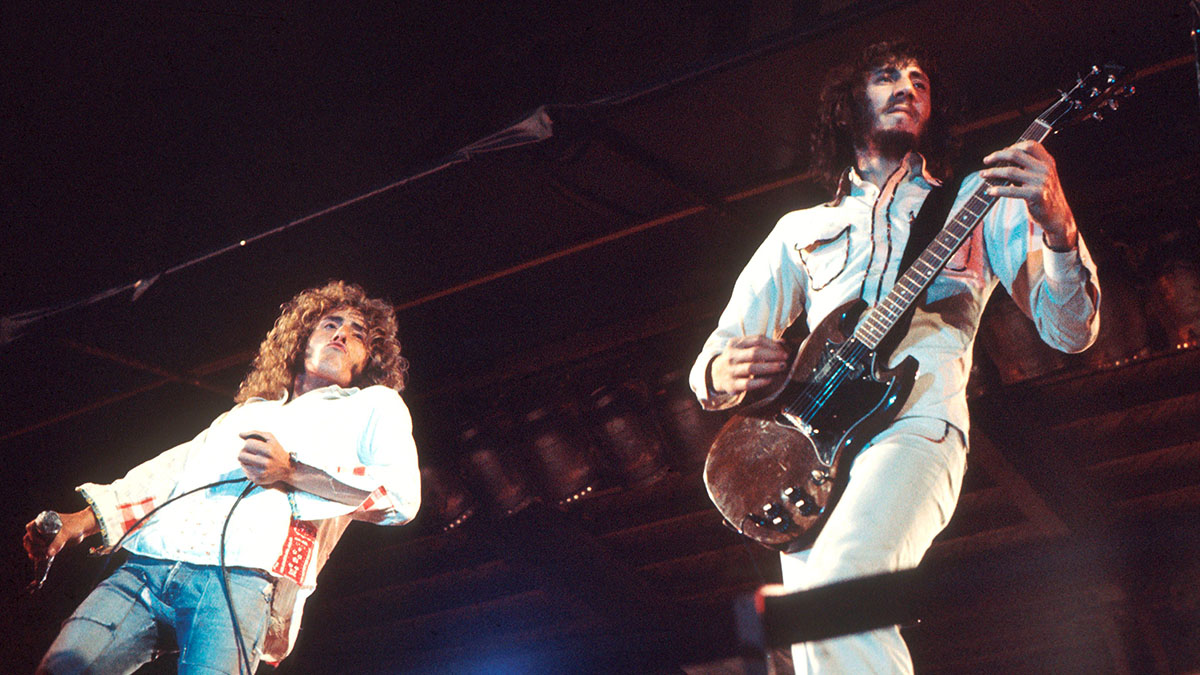

Far from it. That album was Who’s Next, one of the most celebrated, balls-out rock albums in the Who’s catalog, let alone classic rock. Crafted from selectively salvaged fragments of Lifehouse, it served up some of the group’s best-known and most loved gems, including “Baba O’Riley,” “Behind Blue Eyes,” and “Won’t Get Fooled Again,” each of which would become a hit and a defining song within the Who’s catalog.

Who’s Next also marked the start of a new era for the Who as both a recording and performing act. Much of that is down to Townshend’s songs and his creative use of keyboards and synthesizers, still a new and novel instrument in 1971. But it’s also thanks to his brawny guitar tone – forged with a 1959 Gretsch 6120, an Edwards pedal-steel volume pedal, and a Fender Bandmaster amp – and the album’s muscular and, 50 years on, timeless production.

Sometimes failures are just failures, and nothing more. Sometimes they are the fertile, nurturing hotbed from which success unexpectedly springs. This is the story of how Pete Townshend’s inability to launch Lifehouse begat one of rock and roll’s greatest albums of all time.

Timing is everything. Had Townshend conceived of Lifehouse 25 years later, it might have been celebrated as a cautionary tale about the rampant growth of digital technology and the emergence of the internet, rather than greeted with thousand-yard stares and polite smiles.

The futuristic fable is set in a dystopian Great Britain, where pollution has forced much of humanity to retreat into womblike Lifesuits attached to the Grid, an internet-like device run by the government, the gas company, and a cable concern.

In addition to food, medicine, and anesthesia, the Grid provides programming that lets its netizens live out virtual lives. Within this world, music and art have diminished value, and are seen as providing little to human experience.

Beyond the Grid, a small collective of farmers have been allowed to subsist in the countryside. Among them are Ray, Sally, and their daughter, Mary, who live in Scotland. One day, they learn of a rock music festival being held in London. Called Lifehouse, it’s the project of a computer hacker named Bobby, who collects raw data from the Grid’s users and converts it into music.

After Mary runs away to attend Lifehouse, Ray and Sally race crosscountry in their van to find her. They arrive right when the concert reaches its peak, as the combined songs from the Grid’s users ring out the perfect note, and the attendees, including those observing the concert from their Lifesuits, disappear in the musical equivalent of the Rapture.

What ultimately alienated us from our fans was the way Woodstock turned us into superstars

Pete Townshend

As Townshend explained, the storyline had been inspired by his own feelings of isolation in the wake of the Who’s growing popularity. As a student in art college, he’d formulated ideas about pop music that elevated it to the height of personal expression.

“Ever since I was in art college, I believed that the elegance of pop music is that it is reflective – it holds up a mirror,” he explained. “And that, in its most exotic and finest sense, it is deeply, deeply philosophically and spiritually reflective, rather than just societally.”

But the Who’s success following Tommy made him fear that intimacy with the audience was lost. The turning point came at dawn, Sunday, August 17, 1969, at the Woodstock festival.

“What ultimately alienated us from our fans was the way Woodstock turned us into superstars,” he told me. “In some ways that was wonderful. We went from being a band with a predominantly male following to one where Roger seemed to be like a new kind of rock sun god. And we had a few women in the audience for a change. But in other ways it was disarming, because the actual natural, easy connection between me, as the writer, and the audience was broken.”

It was also at Woodstock that Townshend began to fear the 1960s teen culture revolution had lulled itself – and pop music – into irrelevance.

As the sun rose that Sunday morning, the guitarist looked out from the stage at the teens camping in the mud of Max Yasgur’s farm and saw not the 1960s’ promised nirvana but the “teenage wasteland” he would evoke in “Baba O’Riley,” the lead-off track to both Lifehouse and Who’s Next.

“‘Baba O’Riley’ is about the absolute devastation of teenagers at Woodstock,” he said, “where everybody was smacked out on acid and 20 people, or whatever, had brain damage. The contradiction was that it became a celebration: ‘Teenage wasteland! Yes! We’re all wasted!’”

With Lifehouse, he hoped to break the massed youths from their slumber and reconnect them with the real world. And he would do it through the power of rock and roll.

“That’s what Lifehouse contained,” he said. “A fear that we were losing an intimate connection with our audience, but also a recognition that there was nothing more important than the simple art of rock music – that it could make us more aware of what was actually happening to us, and to our duty and our responsibility to ourselves.”

Unfortunately for Townshend, no one could understand what that had to do with Lifesuits and virtual reality.

To explain, he relied on an analogy using the BBC, which, like his fictional Grid, is regulated by the U.K. government. “I would tell people, ‘Well, you know what we do with TV. We sit in front of it, and we turn the lights out and we watch it, and we don’t listen to pop music.

"Well, imagine that – a bit more. So instead of turning on the television and watching a soap opera, you experience a soap opera. Get it?’ And of course everybody got it! “And then they would say, ‘Yeah, but why is this in the story?’ And I would say, ‘Because what’s at risk here is our karma – our free will to choose our destiny.’ And that’s where I lost them.”

If the Lifehouse plot seemed convoluted, there was no denying the sheer power of its songs. The brisk romp “Going Mobile” is about the joys of life beyond the Grid, but its exuberant celebration of freedom could be understood by anyone who owned a car. “It was originally a song about driving in America,” Townshend said. “In Lifehouse, it’s a song about escape from duty and responsibility, about being able to run away.”

Likewise, “Behind Blue Eyes” lays out the dilemma – previously explored by Townshend in “The Kids Are Alright” – of conflicting loyalties to one’s peer group and self. It was perhaps the most personal of the songs he wrote for Lifehouse. In the original score, it was sung from the perspective of Brick, a Judas-like disciple of Bobby’s who attempts to shut down the Lifehouse.

“In the song, he’s reflecting on his disloyalty,” Townshend says, “on whether he’s betrayed his own values system.” While these and other tunes were played out largely as standard three-piece rock tunes, a few of the songs Townshend wrote for Lifehouse relied heavily on keyboards and synthesizers, both of which were new to the Who’s sound. Indeed, synthesizers were just being introduced to the market, and Townshend had purchased ARP’s top-of-the-line 2500 modular system.

Despite his owning such a luxury piece of gear, the ARP’s tones are heard very little on Who’s Next, largely on “Bargain,” “Going Mobile,” and “The Song Is Over.” The arpeggiating lines that percolate through “Baba O’Riley” were created on Townshend’s Lowrey Berkshire Deluxe TBO-1 organ, while the pulsing keyboard on “Won’t Get Fooled Again” is the Lowrey plugged into his ARP, with its output modulated by a square wave to create tremolo.

Townshend reserved the record’s most striking use of synthesizer for his guitar solo on “Going Mobile,” where he plugged his Gretsch 6120 into the ARP’s envelope follower to create what he called a “fuzzy wah-wah sound.”

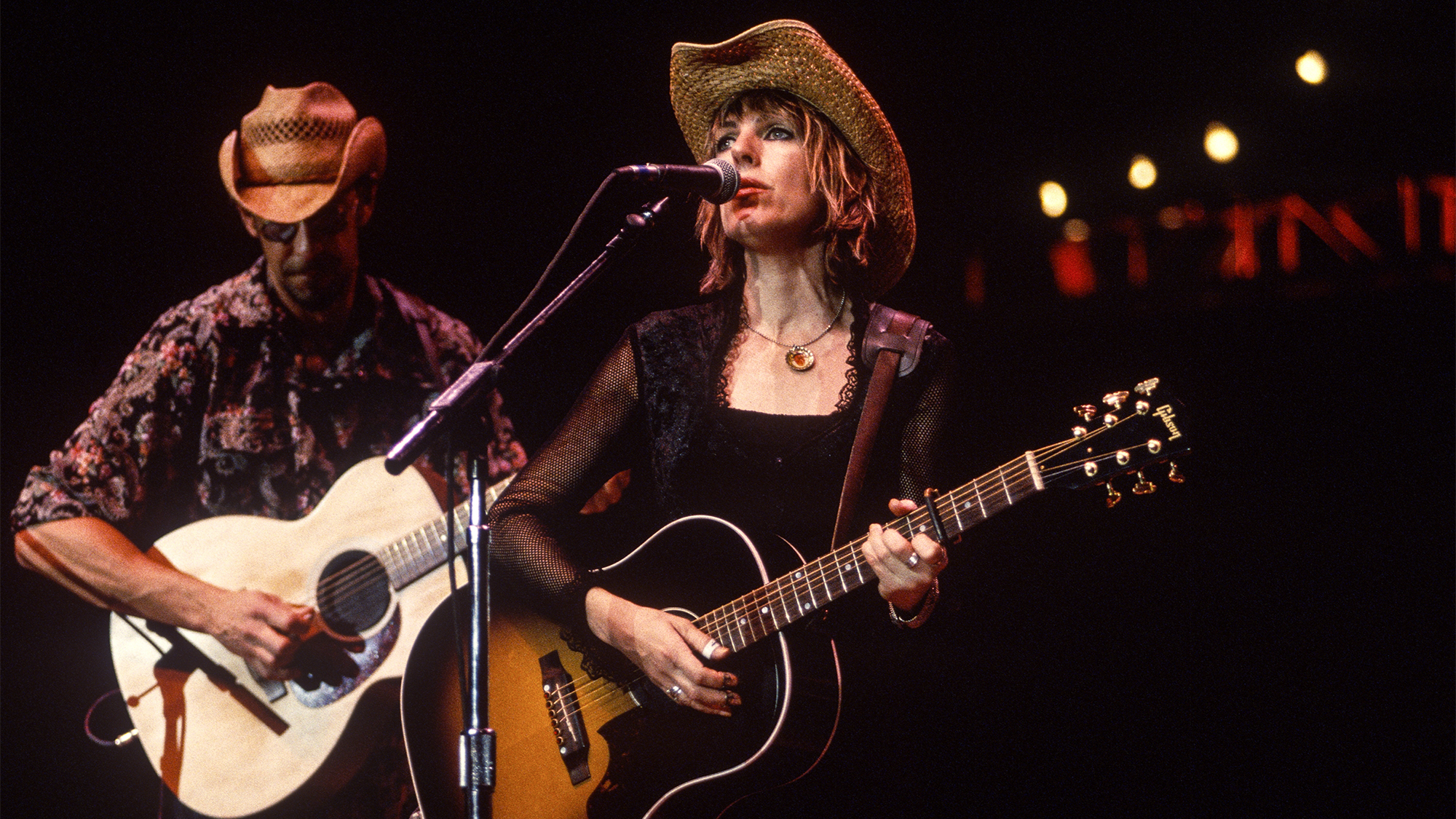

These and other Lifehouse songs had their first public airing in February 1971, when the Who held a series of unadvertised shows at the New Vic theater in London to test the material for whomever showed up. Unfortunately, few did.

“It was disturbing. The place was empty,” Townshend told me. “There weren’t Who fans there. It was people we’d invited in off the street. Local kids.” It was then that he received the call from Kit Lambert to record the album in New York City, at the Record Plant.

Though it had opened just a few years earlier, in 1968, the studio received a boost almost immediately when the Jimi Hendrix Experience recorded some Electric Ladyland tracks there. Townshend welcomed the opportunity to work there and, more over, to reconnect with Lambert and sort out Lifehouse.

Unfortunately, the manager was simply eager for the Who to get on with business, wrap up the album and make some much-needed money. Unbeknownst to Townshend, Lambert was hooked on heroin and in need of cash. The delays caused by Lifehouse embittered him, but Townshend, deep into his rock opera, was oblivious: “I thought Kit was going to help get Lifehouse going.”

The Who’s two-week stay at the Record Plant began on March 15. Over the first few days, they recorded versions of several tracks, including “Won’t Get Fooled Again,” “Love Ain’t for Keeping,” “Behind Blue Eyes,” “Pure and Easy,” and “Getting in Tune,” then titled “I’m in Tune.”

Townshend’s insistence that the group record live resulted in one of the greatest guitar tandems of all time when the late Leslie West was recruited to assist on a cover of Marvin Gaye’s “Baby, Don’t You Do It.”

The Who had featured the Motown oldie in their mid-1960s live shows, and Townshend wanted to include it in Lifehouse as a song that Ray and Sally play in the van when they’re “going mobile” in search of their daughter, Mary.

“Kit Lambert had called my manager, and then they called me and [asked] do I want to play guitar with the Who on this album that they were doing,” West explained to Ritchie Unterberger for his book, Won’t Get Fooled Again: The Who From Lifehouse to Quadrophenia.

“I said, ‘Well, they have a guitar player.’ They said, ‘Well, Pete didn’t want to overdub, he wanted to do it straight away.’ And I said, ‘Sure.’” Less-hallowed pairings have undoubtedly taken place with greater deliberation. West explained further to Gibson.com, in 2011, that Lambert told him, “Pete didn’t want to play lead guitar...he wanted me to play.”

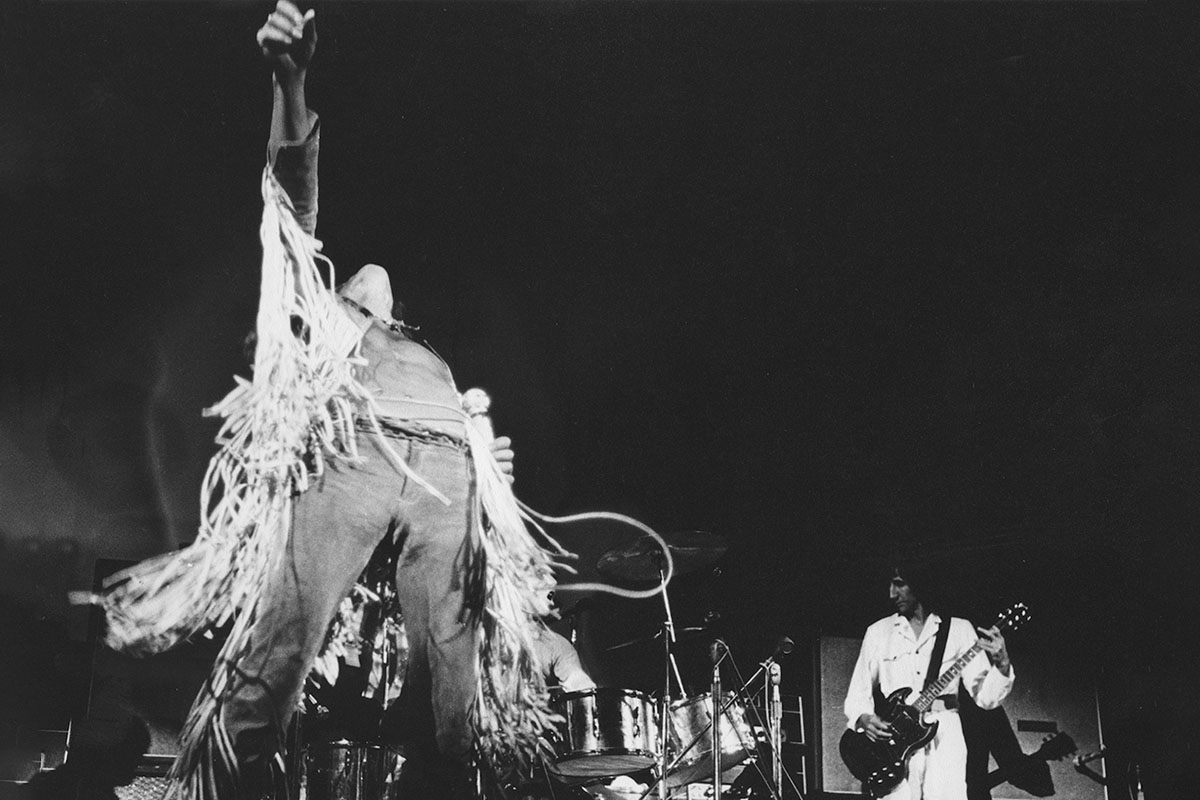

Certainly, West was no stranger to the Who. The New York City guitarist’s band the Vagrants had opened for them at New York’s Village Theater in November 1967. For that matter, West’s 1970s hard-rock group, Mountain, played Woodstock the same night as the Who, and he had hung out with Townshend and Moon at London’s Speakeasy club.

Townshend even admitted to nicking some of West’s licks “for the stage” in a December 1971 interview with ZigZag, a British rock magazine from the time. As it happened, both the Who and Mountain were among the loudest live acts of the early 1970s, and West confirmed that neither he nor Townshend turned down in the studio. “I was using a very small Sunn cabinet, with one 12-inch speaker, and a 50-watt Marshall.”

West told Gibson.com. “Townshend was using his Hiwatt amps, and he said to me that he wanted to be the loudest.” What followed was the mother of all volume wars. “Afterwards, he came over to me – I guess he was a little embarrassed – and said, ‘Can you hear yourself okay?’ I told him I could hear myself even if I was in Chicago.”

Jack Douglas vividly recalls the sessions. Famous for his work with John Lennon and Yoko Ono, Cheap Trick, and Aerosmith, among others, the engineer made his rock session debut on these dates.

“Kit Lambert was technically listed as the producer, but it was clear that Pete was in charge of the production,” he told Guitar Shop magazine. “He could drive the band nuts with his directions but also really got them ripping when they tracked.

“He would especially concentrate on whipping up Keith, because he realized that the band actually took its energy cues from Keith. The energy level was always so up there that many of the solos on the record were done in one pass during the tracking sessions. It really kept the trio sound together.”

Unfortunately, Townshend was falling apart. The Record Plant was the first recording facility to provide artists with a comfortable and more casual environment, and activities typically reserved for outside insinuated themselves into the studio. In addition to Lambert’s heroin abuse, Keith Moon had begun using hard drugs, and Townshend recalled drinking bottle after bottle of brandy at the dates.

Although the sessions were supposed to run for two weeks, they became unproductive after just a few days. Townshend decided to call a band meeting in Lambert’s suite at the Navarro Hotel on Central Park South.

As he approached the door, he recalled, he could hear Lambert speaking angrily to his assistant, Anya Butler, about the guitarist and his troubled project, “and calling me ‘Townshend.’ And as I walked in, he said, ‘Oh – hello, Pete!’”

Townshend’s face caved at the memory. “And I sat down, and I thought, When I’m not doing what people want me to do, I’m this arrogant shit called Townshend, and people hate me. And I started to kind of come apart. And I thought, This is not going to be how I thought it would.”

“Kit was the only one who could really communicate to Pete what was good and what was bad, and Pete would accept it,” Roger Daltrey explained in the Classic Albums documentary about the making of Who’s Next. “He wouldn’t accept anything otherwise.”

It was then that Townshend’s panic attack began, followed by his rush to the hotel room’s open window and the quick action of Anya Butler that prevented his almost certain defenestration. Townshend survived intact, but his spirit was broken. Suffering from nervous exhaustion, he called off the remaining Record Plant sessions. “And that,” he said, “is when I gave up on Lifehouse.”

Back home in England, Townshend wasted no time. In short order, he hired Glyn Johns to assist with the project, a decision that proved key to getting the album off the ground.

“It had been very much a question of seeing how it went,” Johns said. “I said, ‘I’ll come and work with you for a week, and we’ll see how we get on, and if it doesn’t work out, you can have whatever we’ve done as a pressie [a present] and we’ll call it quits.’ But it worked out really well, so we carried on.”

The project began anew in early April when the Who recorded the backing track for “Won’t Get Fooled Again” at Stargroves, Mick Jagger’s country estate, using the Rolling Stones Mobile Studio. The session was productive, and at Johns’ suggestion they moved the project to Olympic, a studio he knew well from previous projects, including Led Zeppelin’s debut, which he mixed.

Overall, Johns made simple but important recommendations that improved the work and results. For one, he suggested that Moon simplify his drumming by eliminating the rolls and fills that typically punctuated his frenetic work on the kit. The drummer complied and was further reined in by having to follow the tempo set by Townshend’s pre-recorded keyboards on “Baba O’Riley” and “Won’t Get Fooled Again.”

Townshend believes that, far from hampering Moon, the rigid timekeeping “liberated him. It meant he didn’t even have to pretend to keep the beat,” the guitarist said, with a laugh. “No, Keith was brilliant. When somebody else kept the beat for him, it was just great. He was just decoratin’.” For another, Johns convinced Townshend to focus on the best tracks and release just a single album.

Freed from the Lifehouse concept, Johns was able to compile the songs – including, by then, the addition of John Entwistle’s song, “My Wife” – in whatever order he felt was best. It was just as well – he was no more able to understand the Lifehouse plot than anyone else.

“Just before Glyn programmed Who’s Next, he took me out to a pub,” Townshend recalled. “He said, ‘Pete, tell me just once more about this Lifehouse.’ I thought, Oh, god! “So I told him the story. And he sat there, thinking. I thought he was going to say, ‘Now I get it!’ And instead he said, ‘I don’t understand a word that you said!’”

The failure of Lifehouse heightened Townshend’s insecurities about his artistic talents, but it also taught him to work more simply, a lesson he put to use on the Who’s next album, Quadrophenia.

“With Quadrophenia, I decided to get a much more loose line,” Townshend explained to me. “I did that thing that one does if one’s working on a short story – to take a glimpse, a slice, and say, ‘This is something: This is three days in the life of a boy.’ That was all, and that will do.”

Scraps from the Lifehouse score would surface from time to time in the Who’s catalog. Three of its songs – “Let’s See Action,” “Relay,” and “Join Together” – were released as singles in 1971 and ’72, while a fourth, “Pure and Easy,” made its debut appearance on the 1974 Who compilation of outtakes, Odds & Sods.

In 1976, Townshend attempted to revive Lifehouse and wrote a new song for it titled “Who Are You?” By 1978, he’d pulled the track free of the lumbering project and made it the title cut of the Who’s 1978 album, their last with Keith Moon.

In the years that followed, Lifehouse was never very far from the guitarist’s mind. It inspired his 1993 solo album, Psychoderelict, a semi-autobiographical story presented as a radio play about an aging rock star struggling to complete a 20-year-old rock opera called Gridlife Chronicles. Psychoderelict, in turn, led him to create a radio play based on Lifehouse, which he presented on BBC radio in 1998.

At last, in February 2000, Townshend opened his vault and released the six-CD set Lifehouse Chronicles, which compiled his demos for the project as well as the Lifehouse radio program. (He also issued a single-disc selection of its tracks as Lifehouse Elements.)

The release of Lifehouse Chronicles was celebrated with a pair of concerts at Sadler’s Wells in London, a video from which was issued as Music From Lifehouse in 2002.

Remarkably, for all his grief over the project’s failure, Townshend embraced Who’s Next for the triumph it was then and remains today. “I was delighted with it. It felt like the Who’s first proper album,” he said. “It felt uncomplicated and simple, and I didn’t care that the story had been lost. I was just relieved to have made anything at all.”

Christopher Scapelliti is editor-in-chief of GuitarPlayer.com and the former editor of Guitar Player, the world’s longest-running guitar magazine, founded in 1967. In his extensive career, he has authored in-depth interviews with such guitarists as Pete Townshend, Slash, Billy Corgan, Jack White, Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren, and audio professionals including Beatles engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott. He is the co-author of Guitar Aficionado: The Collections: The Most Famous, Rare, and Valuable Guitars in the World, a founding editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine, and a former editor with Guitar World, Guitar for the Practicing Musician and Maximum Guitar. Apart from guitars, he maintains a collection of more than 30 vintage analog synthesizers.