"I don't think I knew four chords when I started recording. All the songs I liked you could play with two or three chords. We made a lot of noise, got into a lot of fights…" Johnny Cash looks back…

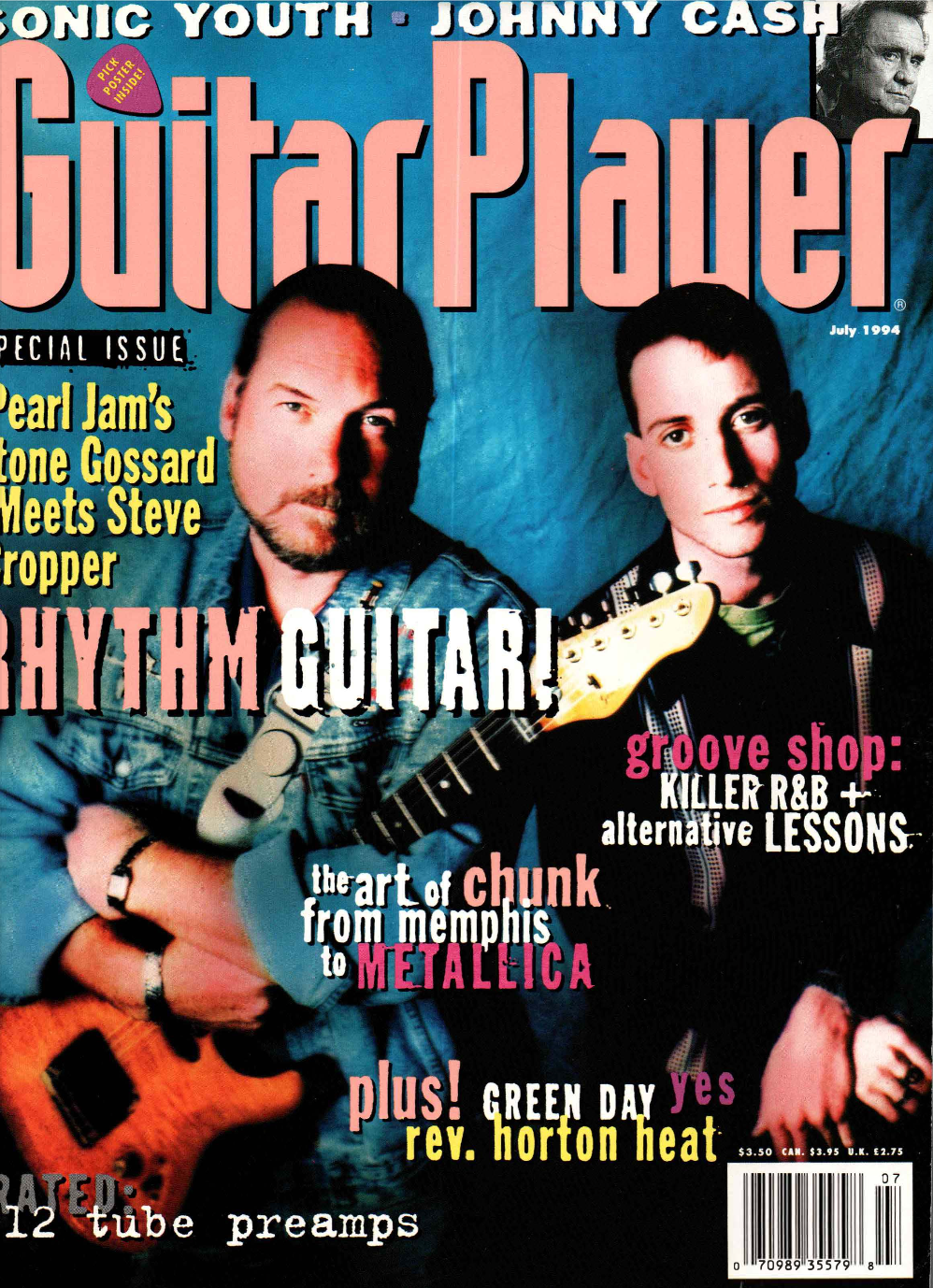

Singing about "death, hell, danger, trouble, killing and murder, blood, and redemption," Johnny Cash's American Recordings marked the beginning of a late-period resurgence. In 1994, he did the Guitar Player Interview…

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Released when the music industry was still reeling from the sudden death of Kurt Cobain just four weeks earlier, Johnny Cash reinvented the American Songbook with his 81st album, an album of originals and covers from the country legend. The first of a six-album series, American Recordings was driven by Rick Rubin and mostly recorded at his home studio, while affording Cash full creative control.

Suffering health problems and a relapse of his addictions, the album marked a resurgence of Cash's popularity, attracting a new generation to his singular talent. This feature originally appeared in the July 1994 issue of Guitar Player Magazine.

Draped in black from head to toe, Johnny Cash cuts an imposing figure against the technicolor blue sky, white clouds, and green grass of a postcard-perfect Tennessee sring afternoon. In his ankle-length duster and embroidered vest he looks like a ntleman gunslinger or gambler, but the tiny, shining gold cross on his lapel contradicts that image, giving him the appearance of a prairie preacher. Picking up his black Martin, he strums a simple chord progression and starts to sing. The clouds soar across the sky, almost as if they're being propelled by his big, resonant voice.

Like Jesse James or John Henry, Cash has become a figure of legendary status. He has been a saint and a sinner, an outlaw and an outcast, a hero and a humanitarian. Tales of sin, deceit, murder, salvation, prison, and war, his songs have become modem folklore. Though many believe otherwise, he was never a prisoner and never murdered anybody. But because he sings "Folsom Prison Blues," "Ring Of Fire," and "Delia's Gone" with unflinching attitude and conviction, many imagine these stories are his own.

Cash's career has been through many ups and downs since he first entered Memphis' Sun Studios in 1954. He has been one of country music's most influential performers, but lately he has been shunned by country radio in favor of younger, less daring performers. Fortunately, Cash has always maintained strong rock and roll appeal. He was recently inducted into the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame and last year was wholeheartedly embraced by rock's elite. He made a guest appearance on U2's Zooropa album and inked an unlikely deal with Rick Rubin's American Recordings. This summer he is expected to perform at several Lollapalooza shows.

Cash's new release, American Recordings, is no pandering rock and roll sellout, however. Featuring nothing more than Cash's voice and simple acoustic guitar accompaniment, the record presents an honest, intimate portrait of Cash that recalls the energy and earnestness of his early Sun recordings. Instead of making the event into a rock and roll circus with dozens of celebrity guests, Rubin had the wisdom to give Cash the freedom that other record labels denied him. ''I've been wanting to do this album for years and years," says Johnny.

Although Cash has never strayed far from the public's consciousness during his 40-year career, the blitz of media attention he is receiving may extend his appeal to new believers. Unlike his peer Elvis Presley, Cash never let himself become caught up in the machinery of being a star. He's always been a friend and a father figure to his fans, yet he's never been afraid to shock and challenge his audience. While his rebellious attitude wins him a new generation of admirers, his gentlemanly demeanor keeps his longtime devotees loyal.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

With his boots firmly planted on the ground, shoulders broadly blocking the wind, head held high, and eyes facing God, Cash enters the latest phase of his career with the same determination and boldness he had as a 22-year-old man stepping into Sun Studios.

This record is so personal and genuine.

It's that dream album that I wanted to do all these years. I remember talking to Marty Robbins 25 years ago about this. I even had the title for 25 years, Johnny Cash Alone. That's really what I wanted to call it, although the title is American Recordings. I've stripped it down to just me, now that I play a little rhythm with my thumb.

Marty Robbins did an album like that. Just him and his guitar, him and a piano, singing songs he always loved and wanted to record. It went a little further than that with me. I had some songs I'd always wanted to record, like "Tennessee Stud," "Bird On A Wire," and "Why Me Lord?" but I wrote a lot of songs. When I got into this thing, the juices started flowing and I started writing. I wrote five songs on the album, four of them within the last year.

How did you go about choosing the material?

Songs came from everywhere. Rick Rubin brought me "Down By The Train" by Tom Waits. That is one of the greatest spirituals I've ever heard. Glenn Danzig wrote a song for me called "Thirteen." There's a Loudon Wainwright III song called "The Man Who Couldn't Cry." Nick Lowe wrote a song for me 14 years ago called "The Beast 1n Me." I recorded songs by Neil Young, Billy Joe Shaver, and Dolly Parton which are not on the album.

How did you decide what material to include?

The way I see this album, it's like showing the worst, evil side of me and then maybe a little of the good side-whatever that is. It's showing the evil that the mind goes through from "hard to watch her suffer but with the second shot she died" in "Delia's Gone" all the way to redemption. There are two redemption songs on the album – one I wrote called "Redemption" and the Tom Waits song. In that song, the train is a symbol of redemption. "Get on this train, and you can be redeemed." Then there's a prayer, "Why Me Lord?" It's got everything in it that I feel, that l can remember feeling, the emotions that l can remember going through.

There are flippant things like, "To hell with it. Let the train blow the whistle when I go." I've taken so many things seriously, but then I'm thinking maybe it's not so good to take myself so seriously. I'm singing a lot about death, hell, danger, trouble, killing and murder, blood, and redemption. I thought about this train that runs by the House Of Cash. They blow the whistle every time they pass here, because I moved this old train station here from Madison. It's on their orders to blow the whistle at the House Of Cash. That's my whistle. I was thinking about that train when I wrote that song. Why complicate every thing? Just let the train blow the whistle when you go. That's all I want.

Why did it take Rick Rubin to bring this record out of you?

It took somebody who had the vision, who knew my work. He knew everything that was wrong with it. He could see it a lot clearer than I could. We started the first day, me sitting in front of one microphone in his living room with an ADAT machine, and started recording. He'd say, "What else you got? Sing something you really like." I loved that about him. By the time I came back the next time, I'd gone over all those songs in my mind, and I had them on a list. So I said, "Have you ever heard 'Bird On A Wire'?"

I put more time in this album than any I've ever done.

I don't remember if he said he had or not. But I sang it, and it's on the album. It's a song I always wanted to record. Then he would mention a song, like an Appalachian song. I'd say, "I know all those, from Bill Monroe and the Carter Family, whoever." I know the standards, the classics. I'd sing a bunch of them, and we put down a lot of them too. We recorded over a hundred songs that way. People would hear that I was recording and maybe listening to songs, and material started coming in from everybody. I called my friends to write songs for me – Paul Overstreet, Waylon Jennings. I brought in all these songs from all these people and we tried them. We finally painfully weeded it down to 13 songs.

I put more time in this album than any I've ever done. When we got all the songs recorded that I wanted to record, we went over the list of our favorites, and listened to all the tapes. Then I'd go in and do them all over until I got the take with the feel I wanted.

You must have done the songs straight through in one take.

Oh, yeah. There wasn't any taking them apart or overdubbing. I had to get a complete take on a song every time.

What guitar did you play?

That black Martin D-28. They made that for me in 1969, and I understand that it's the first black Martin ever made. That's the one that's on almost all the songs. On some of the songs there's my D-76 Martin. It was made in 1976. It's a bicentennial Martin, #365 out of 1,976. It's a good guitar.

What made you decide to become a musician?

I heard a song on the radio, "Hobo Bill's Last Ride," when I was three. It was just an acoustic guitar and a singer. I don't remember if it was Jimmie Rodgers, I think it was somebody else a little later than Jimmie. But I memorized the song when I was three, and by the time I was four I was singing that song for all the neighbors who would come over to the house. My mother would play it on her guitar and I'd sing it I knew then that's what I wanted to do with my life.

It was always those songs like "Hobo Bill's Last Ride" and the simple country gospel things, people like the Chuckwagon Gang, that inspired me, those three or four people that would sing to just one guitar. I thought that was the greatest thing in the world. I knew at a very early age that you didn't have to play guitar like Chet Atkins to get on the radio. That sounded good to me.

I never seriously thought about doing anything else, never once-even when I got out of the Air Force and went to Memphis and was beating on doors trying to get on radio stations. Finally the manager of a radio station in Corinth, Mississippi, called Keegan's School of Broadcasting in Memphis, and I got enrolled there. I knew I was going to sing on the radio, but first I had to get on the radio. I went to broadcasting school five months, half-time. I studied everything that had to do with broadcasting and radio stations. Halfway through I finally managed to get into Sun Records with my first recording, and I quit the school. I was doing what I wanted to do. I had a record out and it was being played on the radio. I was a radio singer.

What inspired you to pick up the guitar?

There was a singer/guitar player when I was 12 years old. He was 14. I'd walk to his house after school, and I'd have to walk home after dark, three miles down a gravel road. He had what they called infantile paralysis-polio-and his right hand and right foot were withered. He couldn't hold a pick with his right hand, but he could beat a really good rhythm on the strings with the end of his fingers and thumb-at least I thought it was good at the time. I had nothing to compare it with.

The sound was so great to me, and I always wanted to play rhythm like that. When I started to learn to play the guitar, I didn't use a pick. It wasn't until I'd been on the road a long time that I used a pick. I just beat it with my fingers. I heard how bad it sounded or the playback once, so I tried to play rhythm with a pick. On my new album I just use my thumb. It's back to the basics. The new album is a kind of feeling that I remember on the first records I ever heard, just a singer and his guitar.

What led you to the guitar in the first place – was it just an accompaniment for your singing?

I don't think I knew four chords when I started recording. All the songs I liked you could play with two or three chords

That's it, yeah. There were four or five of us who got together in the barracks in Germany. We even gave ourselves a name. We were stationed in Landsberg and we called ourselves the Landsberg Barbarians: We played these honky tonks and gasthauses at night in little towns around the base. There was always a big fight, a lot of broken glass and broken bones, broken noses and so forth. It was an acoustic band. There were no electric instruments. I think it was three guitars and a mandolin.

One guy played what we called lead guitar, a guy named Orville Rigdon. I bought myself my first guitar, a German guitar. Paid 20 marks for it, which is five dollars. Then there was a mandolin player from West Virginia, Freeman was his last name, and Reed Cummins from Mississippi. I thought we sounded great Reed played a big flat-top Gibson with a pick. Orville Rigdon had a Martin, and he played all the melody. He taught me some of my first chords on the guitar. I knew two that my friend, Jessie Barnhill, the guy with the polio, taught me when I was 12. I don't think I knew four chords when I started recording. All the songs I liked you could play with two or three chords. We made a lot of noise at those gasthauses, got into a lot of fights. The police came a few times.

What kind of music were you playing?

Whatever country songs were popular, a lot of Appalachian because Freeman was from West Virginia and knew all those songs. So did I. I listened to them all my life, sang a lot of Bill Monroe. My voice was a lot higher then. Hank Snow was one of my great inspirations. I loved the way he played the flat-top guitar. He still plays it.

Let's talk about some of the guitarists you've played with, starting with Marty Stuart.

Nobody can play like Luther Perkins. Nobody yet has ever got that particular touch that Luther had on playing that one-string rhythm

He's really good. He's one of the best He did a great job, and we had a lot of fun together. He worked with me a long time. I really liked his playing. He's a good all-around musician. His instrument is the mandolin, but he's a great guitar player. He's better than he thinks he is, and he thinks he's pretty good. [Laughs.) And he's a good singer. I love to do some of the old stuff with Marty, like "Doin' My Tune," which was on my first album. We had a lot of fun with that one onstage. Songs like John Prine's "Paradise" – we sang that together. He added an element to my show that wasn't ever there. It felt good.

What about Luther Perkins earlier in your career?

Nobody can play like Luther. A lot of guitar players have come along who try to sound like him, but nobody yet has ever got that particular touch that Luther had on playing that one-string rhythm. Luther Perkins was a nice person too. Everybody liked him. I loved him like a brother. We were closer than brothers really, from day one when we started working together. He had this tiny Sears amplifier with what must have been an 8" speaker, and that's what we used on our first shows.

Marshall Grant played the upright slap bass. Luther was a radio technician at a car dealer in Memphis when we started working together, and he'd never played professionally anywhere. He'd never been onstage with that guitar. The first big show we did was Elvis' show over at the Overton Park Shell, in August '55. From day one everybody loved Luther. All the guitar players immediately started trying to imitate him. Every artist that imitated me would have a guitar player that would try to sound like Luther. They're still doing that, which makes me feel good for Luther.

You really developed a unique sound.

It wasn't something we cultivated. It was just what we did. It was the only way we knew to play

Well, that's the way we sounded. We didn't know we were that different until people started telling us. We honestly didn't. We just played what we had and played the only way we could play. Marshall got that extra little beat on that slap on the bass and Luther got that boomchicka-boom, the double beat on the guitar, and I played what little rhythm I could play. When I first started recording, I thought I probably sounded like Hank Snow, but I'm the only one who thought that. I didn't sound like anybody, I guess. But it wasn't something we cultivated. It was just what we did. It was the only way we knew to play.

What was the benefit of being in Memphis at that time?

It was the freedom. I couldn't have done that in Nashville. Come to Nashville for a session, and they'd say, "Well, who's going to play fiddle? Who's going to play the steel guitar? Who's going to play piano?" Sam Phillips was taking our music in a new direction, and he knew it. He protected that. He didn't want a fiddle in the studio. He didn't want a steel guitar. Not that I've got anything against those instruments, but they just weren't part of the sound that we had. It didn't work.

Country music was beginning its record machine mode-all the same musicians playing on all the records, the A team. They've still got the A team, the B team. The fewer minds you've got pulling when you're making music, the more honest and, to me, the better it will sound – where it doesn't sound like the music was made by committee. It was made by feel. It was really comfortable playing it that way.

How do you feel about facing a young audience at this year's Lollapalooza festival? You've faced some tough audiences before, like in prisons.

Yeah, but those are good audiences. Like at the Viper Room in LA. and in Austin at Emo's, South By Southwest, I just took my guitar onstage and sang songs from the album, and they listened. How much more musical integrity can you have than that? They appreciate the honesty of performance. It may not be too good, but they appreciate it anyway. For safety I brought on a rhythm section – a guitar, bass, and drums – and I did some of the old stuff to close the show. I think there's going to be an acoustic side stage when I do those shows.

Why did you decide to do the prison shows?

I played my first prison in Huntsville, Texas, in 1957. That was a paid engagement, singing things like "Folsom Prison Blues," "The Prisoner's Song," things that they could relate to. It went over really well, and the word got around in the prison grapevine that I was one of them. I started getting requests from prisons everywhere, so I started performing. I played the New Year's show at San Quentin four years in a row, '58 through '61.

Then the requests kept coming in from everywhere. I always wanted to go back to Folsom and San Quentin and record to get that sound on record. It was so fabulous. I wanted everybody to hear it. So we finally did. Bob Johnston produced the albums. We went back to Folsom in '68 and San Quentin in '69 and did the albums there. Ever since then I've played a lot of prisons.

I really was interested in some form of prison reform, but I don't think that's the answer. The answer is out on the street. Jobs. Opportunities. Racial prejudice is another thing that's wrong and is a reason for the crime and drugs too.

When you came to Sam Phillips' studio, you were pushing yourself as a gospel singer.

I wasn't really pushing myself. When I was getting together with the band, I was singing all these old gospel songs in Germany with the group, and I wrote this song "Belshazzar," which I really thought was a good song. I thought it could be recorded like the old gospel quartets and be one of those songs everybody would like. As a matter of fact, when I put it down on the audition, that's the recording that came out later. I thought that gospel was my forte. In a way it still is 'cause I love it.

But Sam didn't like it. He said, "We're a small independent record company. We can't make enough money on gospel to stay in business." So I said, "Okay. I'm a country singer." I fully intended to record gospel sooner or later, which I did. But I never did push for gospel when I was on Sun. Columbia was like, whatever you want, so the second album was a gospel record called Hymns. Now things have changed. There are three or four spiritual or gospel songs on this album that feel and sound real, that anybody can relate to. You don't have to be steeped in Southern gospel, you don't have to have that heritage to understand these songs and feel them.

Has your spiritual background helped you maintain such a long, prosperous career?

It's been my strength-my faith in God and my spirituality. My kind of spirituality is positive power. I know without a doubt that it's the hand of God that's brought me through a lot of my self-destructive times. I can almost hear him say, "Not yet, Cash. I'm not through with you yet." He'd straighten me out and slap me. Then for a while I'd straighten out. [Laughs.]

Until you got too sure of yourself.

Yeah, until I got my ego packed in again – trippin' with ego and losing sight of God. Then I'd have to be slapped again.

What would you cite as the definitive Johnny Cash song?

Except for "I Walk The Llne," which is a real signature song, it would be "Man In Black." That was a thing that I wrote for the campus show I did in 1971, one of my regular TV shows. Everybody asked me, "Why do you wear black?" In the lyrics of the song I pointed at the black as the symbol for social consciousness, that I was aware and mourned things such as the loss of a hundred Americans a week in Vietnam, our treatment of the elderly, our great illiteracy factor – 25 million functionally illiterate American adults – the people who did not have the peace and comfort of believing in God, the social ills of the day. I pointed out myself as being one of those people responsible for change. I don't hardly ever sing that song. I still get a lot of requests to do it, and when I'm really called on to, I do.

You've always had a wide crossover appeal.

I believe many people didn't know what category to put me in so they said, "Maybe he's for me." I don't know. Maybe we spread the edge out a little further.

This feature originally appeared in the July 1994 issue of Guitar Player Magazine.