“It was possibly the most difficult album I’ve ever done. It came out screaming.” Guitarist Steve Hackett on Peter Gabriel, Brian Eno and the making of a prog-rock classic

Genesis's sixth album gets a belated deluxe 50th anniversary box set this fall, but Hackett is serving up cuts of 'Lamb' on his own

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

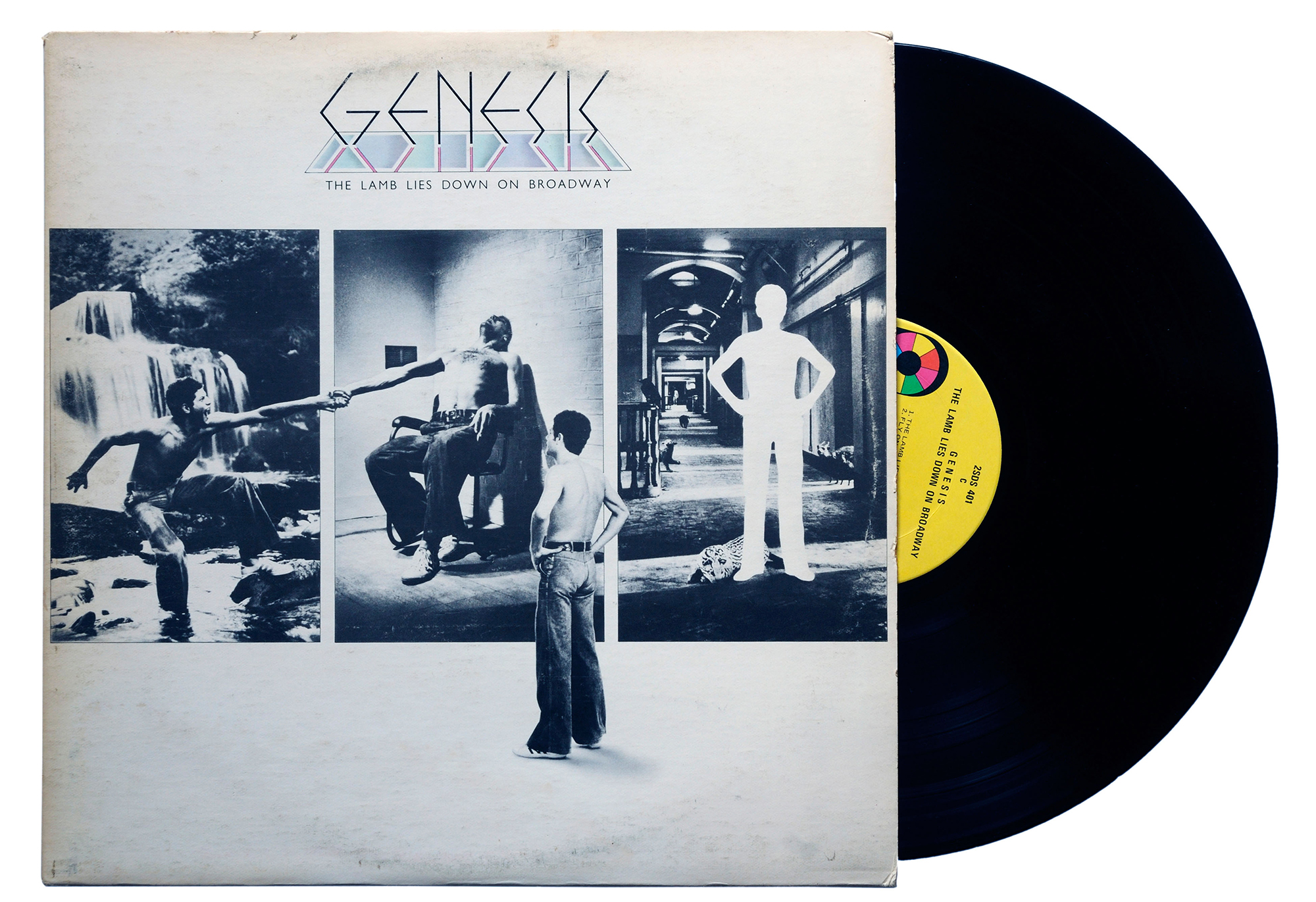

It’s the year of The Lamb for Steve Hackett. Genesis is celebrating its 1974 concept album/song cycle/rock opera The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway with a belated, deluxe 50th anniversary box set whose release has been pushed back several times and is currently due in September.

But Hackett — who served as Genesis’s guitarist from 1971 to 1988 — is serving up some Lamb on his own. His new live album and video, The Lamb Stands Up Live at the Royal Albert Hall, recorded at the iconic London theater last October, comes out July 11, and he’ll be featuring Lamb highlights during upcoming tour dates in Europe and North America.

“It’s a watershed album,” Hackett tells us via Zoom from his home in England, and that may even be an understatement. Genesis’ sixth studio album and the follow-up to the previous year’s Selling England by the Pound multiplied the quintet’s already demonstrated creative ambitions manyfold, both musically and conceptually.

Inspired by a number of acknowledged works — including Carl Jungian psychological theories, John Bunyan’s Christian-themed allegory The Pilgrim’s Progress, West Side Story and Alejandro Jodorowsky’s 1971 Western film El Topo — frontman Peter Gabriel subjects Rael, a New York street youth/graffiti artist, to a trippy journey of self-discovery that includes encounters with carpet crawlers, supernatural anesthetists, Slippermen, flies on windshields and grand parades of lifeless packaging.

“Huh?!” you may say?

That was kind of the point.

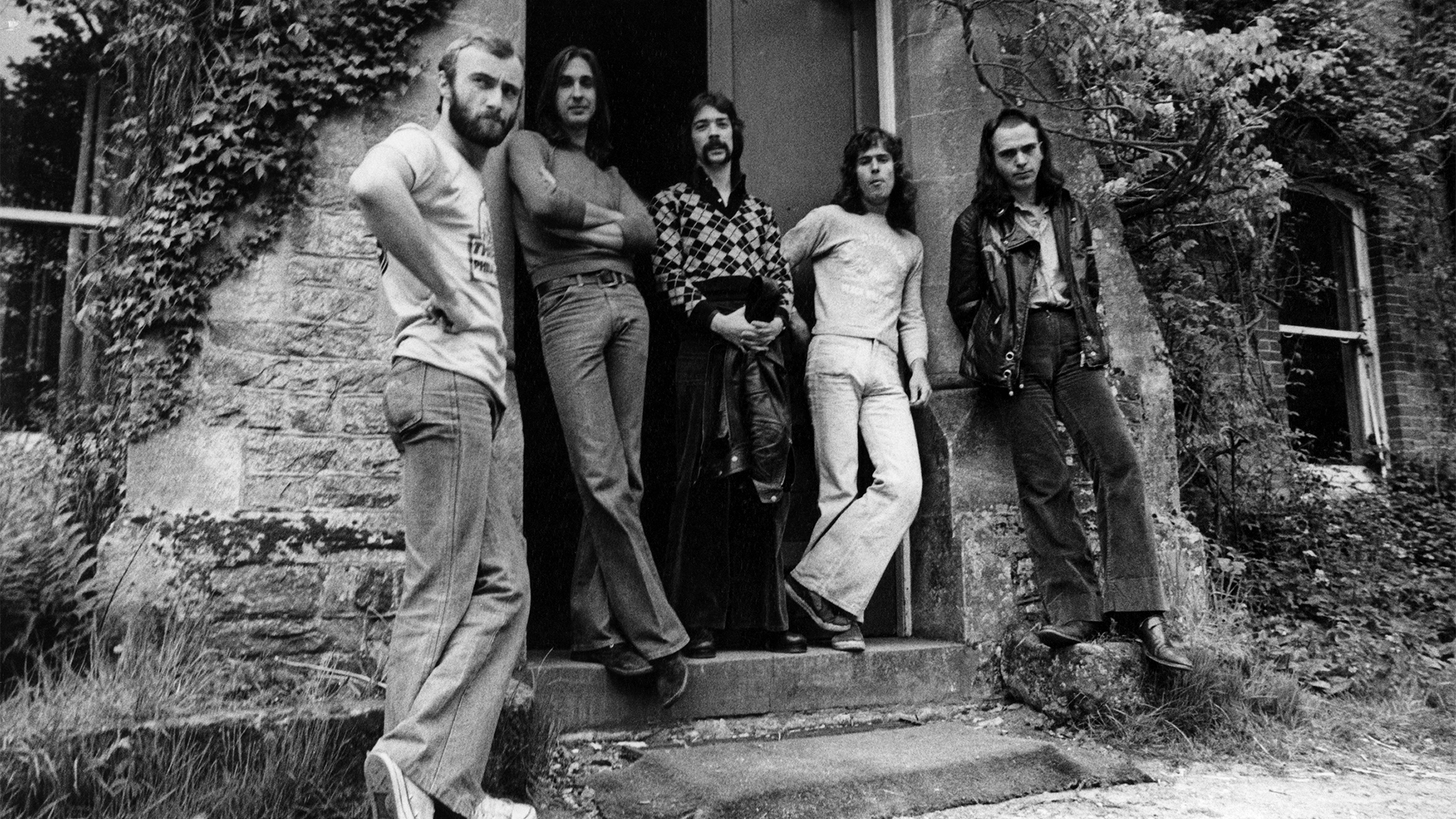

Genesis’ instrumentalists, meanwhile — Hackett, keyboardist Tony Banks, guitarist/bassist Mike Rutherford and drummer Phil Collins — soundtracked the swirl of surrealistic adventure with music of scope, beauty and nuanced intricacy. The Lamb’s 23 tracks range from grand bombast to ambient orchestrations, all leading to the rocking, riffy catharsis of the closing track, “it.” Unapologetically indulgent, it’s a prog high-water mark that felt like a masterpiece when it was released and has aged well during the intervening years.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

The Lamb was accompanied by an abundance of drama as well. The group decided on a double album before it began writing, working to task at Headley Grange, the former workhouse-turned-musicians-residence used by Led Zeppelin, among others. Gabriel dominated the conceptual process, and he also didn’t endear himself to his bandmates when he left the sessions for a time to work on a project with filmmaker William Friedkin.

He was also absent at times tending to his wife Jill’s pregnancy with their first child while the rest of the band worked in Wales, and he was still working on lyrics after the basic tracks had been recorded. The stage presentation of The Lamb also had to be prepared while the album was being finished, with mixing finalized just four days before the launch of a 102-date tour, where The Lamb was performed in its entirety.

The album and subsequent tour marked the end of Gabriel’s tenure with Genesis. He announced his impending departure to his bandmates during the road show, making it public after it ended on May 22, 1975, in France. He launched a solo career in 1977 while Genesis soldiered on with Collins stepping out front, a quartet until Hackett’s departure and then a trio that called it a day in March 2022.

The Lamb was a memorable last shot for that quintet lineup of the band, and Hackett is a willing witness to the continuing appeal of that seminal piece of work...

Let’s start with a general overview of The Lamb and why you think it continues to be such a tentpole.

I think it’s very well written. I think it was designed to be controversial in its day. It was possibly the most difficult album I’ve ever done. I like to think some albums are a little bit like the Immaculate Conception — everything was easy, it was wonderful, the angels came down, wonders were performed. [laughs]

On the other hand, with The Lamb it was a little bit like a breach birth. It came out screaming, yes, the aspect of The Omen, devil’s spawn, all of that — the band dogged by circumstance.

What you get is a band whose lead singer was about to depart, but with his swan song he was treating Genesis almost like it was an extension of a solo career by this point. And yet, in the midst of all that, we came up with what I think is an extraordinary album.

The writing process for The Lamb was a bit different than how Genesis had worked before, right?

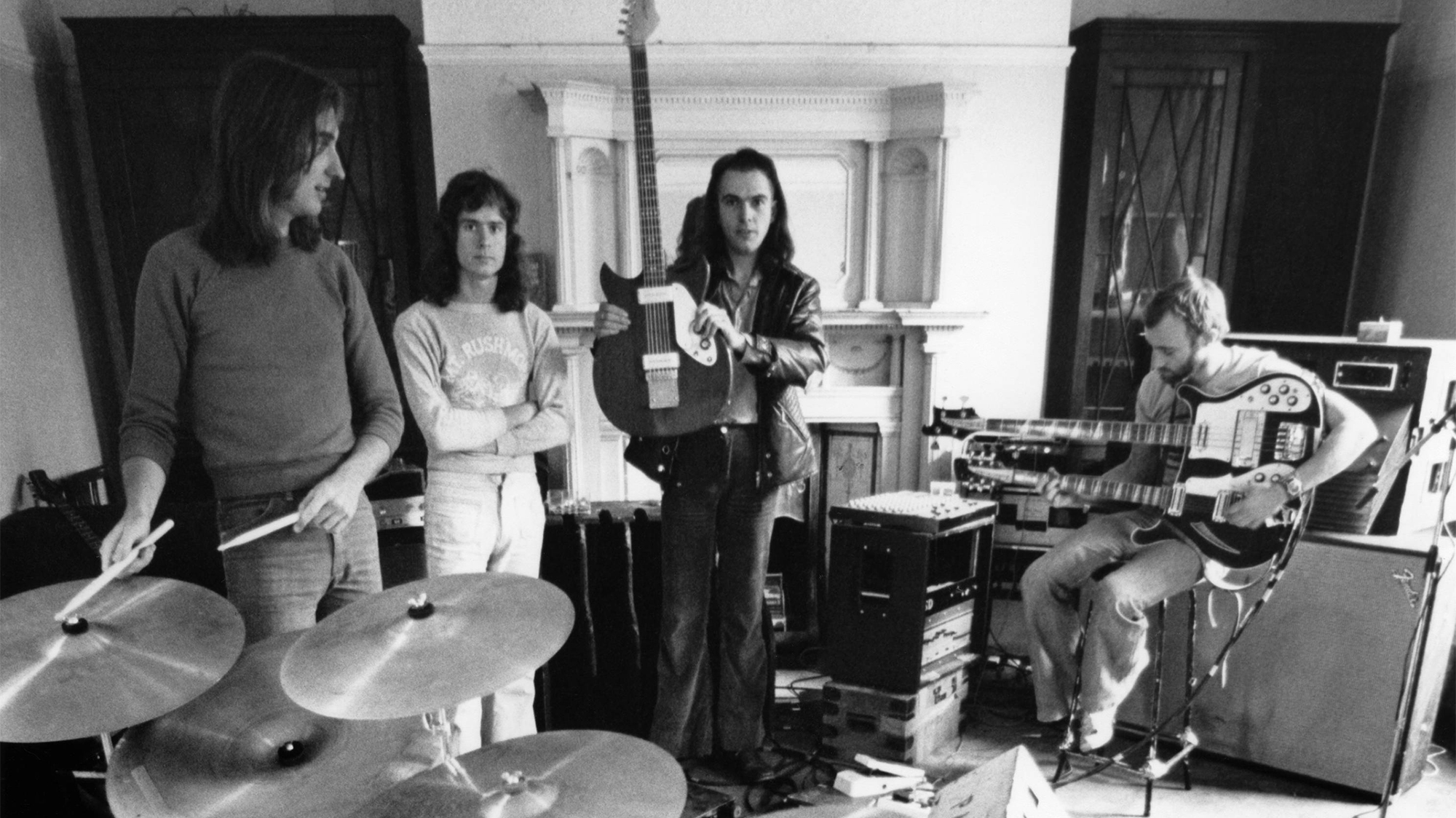

The band, the four of us, were writing in one room, and Pete was in another room writing lyrics. Then we would convene and confer [laughs] and thrash out a kind of agreement about where to go next. Some things that were intended to be instrumental sections ended up becoming vocal sections.

'The Lamb' was a little bit like a breach birth. It came out screaming, yes, the aspect of 'The Omen,' devil’s spawn — the band dogged by circumstance."

— Steve Hackett

It wasn’t as if there was an overarching presence or somebody guiding this — the missiles were firing in all directions, much like modern politics. I didn’t mind that Pete wanted to write all the words, but... it was a time where you had to have your helmet on, really, to make sure the album was completed under very difficult circumstances.

But it has its beautiful moments. It has virtuosic keyboard parts. It has beautiful lyrics. Sometimes they relate to each other, sometimes they don’t. There are beautiful tunes, like “The Chamber of 32 Doors,” which I think was actually less about Rael and more about Pete’s frame of mind at the time, a similar lyrical stance that he was taking a little bit later on with “Solsbury Hill” — “Where to go next? Do I stay or do I go?” He was very much on the fence at that time.

What did you feel like your charge was during this process?

I wasn’t really thinking like a guitarist; I was thinking as someone who was interested in improving the presentation of what the band could do. I felt The Lamb was less about guitar than Selling England by the Pound, which was very guitaristic. The Lamb has its moments, but it really felt like I had to sit back and let things happen.

Many people might have said, “Nope, I’m not putting up with that. I’m gonna steam in here…” But I was ever the diplomat; if you want to stay in a band you have to have a diplomatic approach. It doesn’t sound like most guitarists should be doing that. Most guitarists should be set on fire and charging into amps and playing it with your teeth and all the rest, or you’re coming up with diplomatic guitar parts, much the same as I suspect George Harrison had to do with the Beatles. ’Cause when you’ve got a battle of the giants going on, you’ve got to be content with the crumbs, in a way.

So how did you then make it satisfying for yourself as a player?

Well for me, there were certain parts — parts you can’t hear on the original mix. For instance, I’m soloing throughout “Carpet Crawlers,” and on later mixes you hear it loud and clear. But I was trying to be a distant violin.

I was influenced by Jeff Beck — there was a Yardbirds track called “Turn Into Earth” that sounded intriguing, like there was an electric guitar, but you could hardly hear it. It sounded like a distant violin. It sounds like perhaps they tried to lose the guitar on that track, and what came out was something that sounded quite extraordinary to me and mystical, and I thought, Let’s do that, something very quiet.

It ended up being so quiet that it was virtually mixed out of all existence. But it’s back there with some of the other mixes, particularly the Surround mix that Nick Davis did some years ago. Right at the beginning, I’m doing noises of a fly buzzing about and very cleverly, especially with the Surround, he managed to make that loop, that fly buzzing about everywhere. That was entirely left off the original mix of the album, as was lots of percussion stuff as well. I think the detail was just lost back in the day.

You’re coming up with diplomatic guitar parts, much the same as I suspect George Harrison had to do with the Beatles."

— Steve Hackett

It was an even broader array of sources you were drawing from for The Lamb, too.

We were huge fans of Ian McDonald, late of King Crimson, soon to be forming Foreigner, of course doing a very different kind of music. We were all impressed by his multi-instrumental ability — sax one minute, Mellotron the next, flute the next, vocals.

The point that wasn’t lost on Genesis was that the band didn’t have to be something that functioned in one direction. It could be pan-genre — many different styles. You could be touched by jazz, influenced by classical music. You could come up with an epic style, or something that’s pastoral. I think the Lamb track “The Lamia,” for instance — if there was ever a pre-Raphaelite song, that was it, and the pre-Raphaelite artist movement was all part of what influenced that Greek mythology, which also influenced the band.

What are some of the songs that really stand out related to your contribution on guitar?

“Fly on the Windshield”: I had license to play the guitar and — particularly live — to do it as long as I wanted. Funnily enough the version at the Royal Albert Hall where [Marillion’s] Steve Rothery joined, we extended that moment, which is arguably on one chord, for seven or eight minutes, trading solos between the two of us.

It’s a piece that’s always haunted me. I’ve always felt there was more to it — orchestral in spirit, at the same time cinematic in one sense. We were influenced by the Ben Hur film score — the “Ramming Speed!” moment from Miklós Rózsa, the Hungarian composer who wrote lots of epic film soundtracks.

So here we are being influenced in 1974 by a film that had been made in 1959. That’s why you’ve got the very simple drums and the plod of the bass pedal whilst I get to solo over it, and the version that’s on The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway is the band literally improvising, listening to each other. We are playing together at the same time, and it’s quite rare, I think, that you’ll get something like that without any overdubs.

Actually I lied, there’s a little bit of backwards guitar I threw in just to make it slightly more interesting. I was trying to be a distant screaming voice at times, the sound of the oarsman, the slaves being flogged within an inch of their lives.

There’s a little bit of backwards guitar I threw in just to make it slightly more interesting. I was trying to be a distant screaming voice at times."

— Steve Hackett

How about “Hairless Heart”?

“Hairless Heart” was something I just wrote for fade-in guitar. So the first part of the melody’s mine, beautifully accompanied by Tony Banks on organ, these organ arpeggios with repeat each on them — very floaty, very beautiful. And then the second part of the melody where it goes louder and the drums come in, that’s Tony’s melody. Then it goes back to my melody, then Tony’s, then out.

It’s a relatively short piece, but it’s wonderful doing it live now. When you’ve got soprano sax taking lead on the second part — Tony’s melody — and it’s twinned with synth and other keyboards, it sounds orchestral. It gets to inhabit a very large region that perhaps it didn’t have originally. So it’s a giant version of what you’ve once heard.

“Cuckoo Cocoon” was you and your brother John’s creation, wasn’t it?

Yes, that was me. It was chord shapes that my brother showed me, and I turned it into a song. The song wasn’t John’s but John and I were living at home, we were talking about things all the time and we went on to work on Voyage of the Acolyte [Hackett’s 1975 solo debut].

“Cuckoo Cocoon,” that’s one of the guitar moments. That came from guitar; “Supernatural Anaesthetist,” that came from guitar; “it.” came from guitar, as did many other moments. There’s this kind of tussle going on for supremacy between very busy keyboards and very dense lyrical passages, and so you’ve got virtuosic accompaniment to things that should be very simple songs. It’s funny how that all worked, but as I say, it was really almost like going to war at times.

There’s a story about how “it.” became part of The Lamb, isn’t there?

There was. Mike Rutherford was writing stuff on 12-string and he came up with the sequence that we layered parts on the top of it. The song was built around his chord sequence. I came up with the salvos that would fly across all of that.

But I don’t really think of it as a guitar tune. I think at times, in order to heal this fracturing band, you had to be the glue. You have to use sticky gloss over so many moments.

The solo on “Counting Out Time?”

I had a Synthi Hi-Fli [multi-effects unit, made by EMS in 1972/’73 and used by David Gilmour among others], and it did a very wobbly thing. It would give you a vibrato that went above the note and below the note, so it would sound like somebody literally gurgling through the solo. It was the technology that was around at the time, putting things through analog synthesizers.

I was trying to play something in the style of Django Reinhardt except for this sound that bore no relation to what he would have played. But the notes were the kind of thing that you might have gotten from the Hot Club du France, or Paris with Stéphane Grappelli. That type of playing, earlier kind of 1930s-meet-1940s style of — I guess you would say trad-jazz, but kind of souped-up, almost bebop in a way. So I was taking the influence of that just to be as controversial as anything else.

Brian Eno is credited with “Enossification” on “In the Cage” and “The Grand Parade...”

It was Pete’s idea to invite him to do that. It was lovely working with him. He was a breath of fresh air; when Genesis was struggling to make sense of itself at times, he was able to come in and have none of that baggage and just suggest things.

He was talking about the importance of mastering, and he came in with little boxes of tricks you could put things through. It was good. It was almost like a sort of pixie or an elf-like approach to what we were doing. It culled it, gave it humor and took it into areas of production that perhaps as the band we wouldn’t have thought to go.

Genesis, by then, was like walking into a gentleman’s club that’s been established for several years, and sometimes things can get a little bit staid at times. So it was very nice for him to walk in and cut a swath through the existing band politics. I think it was important, and I think an important step toward Brian Eno’s eventual future as a gifted producer.

Are you happy with the latest mix of The Lamb that’s coming out on the box set?

I haven’t heard it. I tend to just sanction things. I don’t get in the way of that. I know that what tends to happen with band politics is that if someone insists on something, it’s likely not to happen. So I have a passive approach to that and I hope whoever’s mixing is gonna honor the detail that was lost originally, found later on, and it may well be lost again.

But I would point to that Surround mix that Nick Davis did and say that was damn good.

And then there’s the live version, I think from the Shrine [in Los Angeles]. It’ll be interesting to hear that again.

Meanwhile I busy myself by doing new things as well, recording new things. We moved into a new house, got a new studio, working with that, working on solo stuff, working on some stuff with Steve Rothery. So I stay very busy.

it’s a mini tour of 'The Lamb' where the guitar has something to say in each of those tunes."

— Steve Hackett

The latest of those is, of course, the new live album and video, and the tour.

The show that I’m doing is celebrating The Lamb. There’s also quite a bit of — or there was up to now — doing stuff from Selling England, but we’re changing that around because some areas have had that show already, so I’m gonna be giving them “Supper’s Ready” ’cause fans are always creaming for “Supper’s Ready” which takes care of about 25 minutes of anybody’s show. [laughs]

You’ll also be playing what you call “the best” of The Lamb. What’s the litmus for “best?”

Well, the songs I was involved with writing, I think — “Hairless Heart,” for instance. I wanted to do things where guitar was relevant to the plot, ’cause otherwise I’d be a bandleader and standing or sitting there entirely tacit where the guitar isn’t driving it.

But those moments where the guitar is driving it, we’re featuring those songs. So we get to feature “The Lamb Lies Down...,” the title track. “Fly on a Windshield” of course, for various reasons. Then it’s “Hairless Heart” followed by “Carpet Crawlers,” then we do a song that used to be called “The Light,” which became “Lilywhite Lilith,” then “The Lamia” then “it.” So it’s a mini tour of The Lamb where the guitar has something to say in each of those tunes.

Gary Graff is an award-winning Detroit-based music journalist and author who writes for a variety of print, online and broadcast outlets. He has written and collaborated on books about Alice Cooper, Neil Young, Bob Seger, Bruce Springsteen and Rock 'n' Roll Myths. He's also the founding editor of the award-winning MusicHound Essential Album Guide series and of the new 501 Essential Albums series. Graff is also a co-founder and co-producer of the annual Detroit Music Awards.