“George started freaking out. He said, ‘I feel like I’m dying.’ And then, Peter Fonda said, ‘Oh, I know what it’s like to be dead.’” Byrds founder Roger McGuinn on the origins of John Lennon’s trippiest track

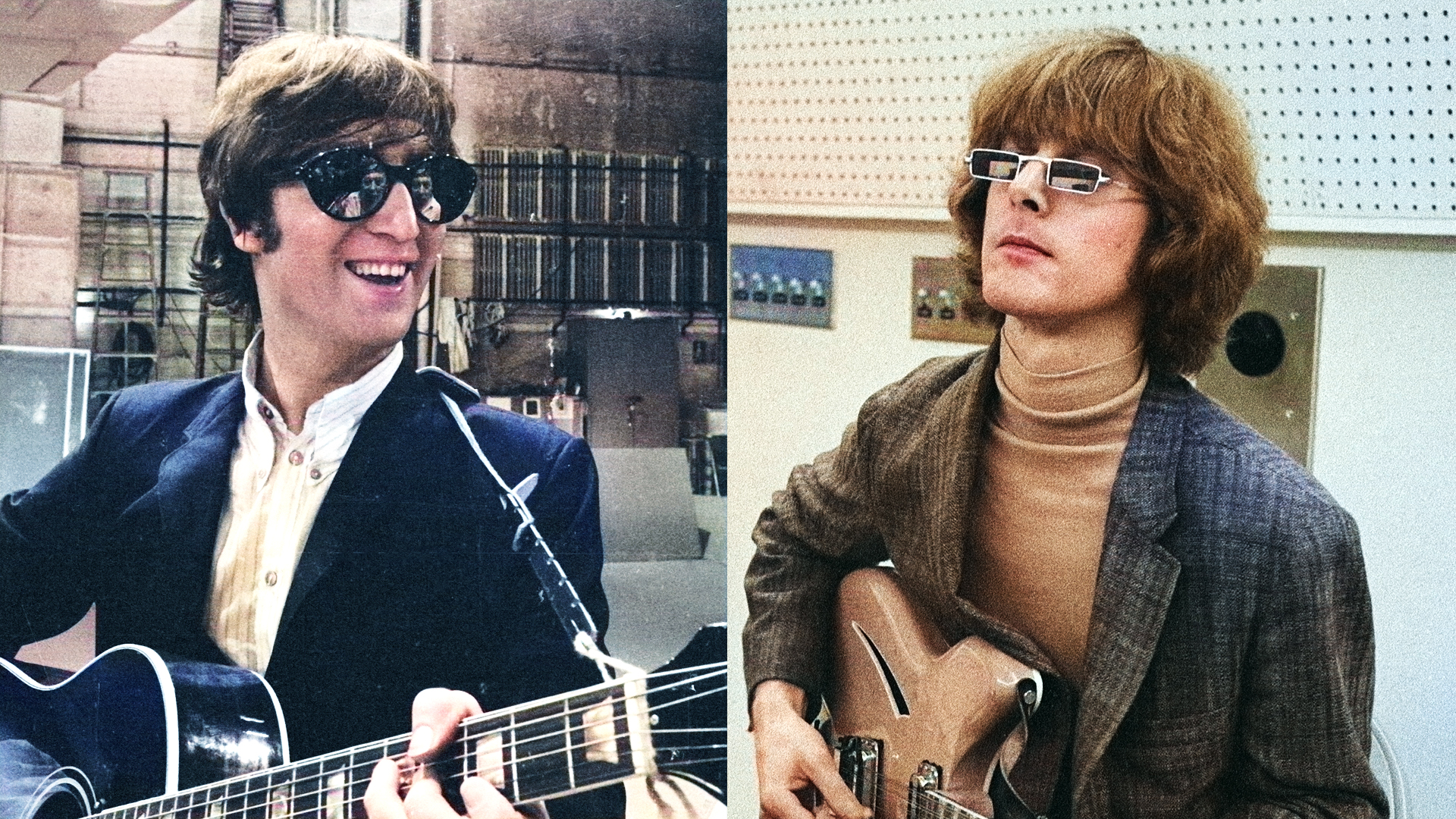

The guitarist reveals the deep friendship between the Byrds and the Beatles at the dawn of the 1960s’ psychedelic era

Before the British Invasion swept the Beatles across American airwaves, popular music in the United States had a distinct sound. Roger McGuinn, who co-founded the Byrds, accented by his now iconic Rickenbacker 360/12 12-string, was a big part of it.

When the Beatles landed in America on February 7, 1964, McGuinn was working as a session player and songwriter, writing songs for singer Bobby Darin’s T.M. Music company. He says that despite Paul, John, George and Ringo being relative unknowns in the States, he was aware of them.

“I was living in New York, and I was a studio musician, and also working as a songwriter in the Brill Building,” he tells Guitar Player. “And as it turned out, I think there was a CBS TV Channel 2 in New York, and there was a clip of the Beatles, maybe about two minutes long. It had girls screaming, and had the Beatles playing… I don’t know if it was ‘She Loves You,’ or ‘I Want to Hold Your Hand,’ but it was one of those songs.

“I went, ‘Man, these guys are good,’” he admits. “I realized they were using folk music chords for rock and roll. They’d come up as a skiffle band, the Quarrymen, and they’d been playing folk tunes with chords they’d developed into a rock band.”

This realization led McGuinn to change course with varied results. “I started putting folk songs to a Beatles beat and taking it to the Village [in New York City] and playing that for people in the coffee houses.

“They didn’t like it,” he adds with a laugh.

But he knew he was onto something. When George Harrison began playing a Rickenbacker 360/12 in 1964, McGuinn — who had been playing 12-string for years — picked on up as well.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

The same year, McGuinn founded the Byrds with David Crosby on guitar and vocals, Gene Clark on vocals, Chris Hillman on bass guitar and Michael Clarke on drums. A 1965 tour followed, orchestrated by their press office Derek Taylor, who had worked for the Beatles in 1964 (and would again from 1968 to 1970). Through Taylor, the Byrds met the Beatles, leading to a friendship between the bands that had a profound impact on both their musical and personal lives.

That impact is evident in George Harrison’s Rubber Soul track “If I Needed Someone.” It also provides the back story to “She Said She Said,” one of John Lennon’s tracks from the Beatles’ 1966 album, Revolver. In August 1966, near the end of their last tour, the Beatles were visiting the Byrds. LSD was a popular drug of choice at the time, and the Byrds and Beatles dropped acid together, along with actor Peter Fonda.

It was Fonda, who, while tripping on acid, said, “I know what it’s like to be dead.”

“Peter had somehow shot himself in the stomach when he was a kid,” McGuinn explains. “He died on the operating table. But they brought him back. So he did know what it was like to be dead.”

Lennon was appalled at the Fonda’s statement. Long after the party ended, still reeling from the episode, Lennon wrote “She Said She Said,” substituting a woman for Fonda, who says, “I know what it’s like to be dead.”

Asked what he made of Lennon’s creation, McGuinn shrugs. “I liked it. I like the song,” he says, “I loved everything the Beatles did, really. There’s nothing that I would put down.”

Despite these connections, the friendship between the two groups is rarely discussed. But the Beatles and Byrds were tight, so tight that when the Beatles gave a press conference at Capitol Records on August 24 of that year, Crosby tagged along.

“Yeah, we were friends,” McGuinn says. “And Crosby kind of followed them around. He’d poke his head out, and whoever was interviewing the Beatles said, “Who’s that guy with the long hair over there?’ And the Beatles would say, “Oh, that’s our mate from the Byrds, David Crosby.’”

Is it true that George Harrison inspired you to start using a Rickenbacker 12-string?

Yeah. We all went to the movies and saw A Hard Day’s Night, and I’d heard that sound on the records, but I didn’t know what instrument it was. But George came out with a Rickenbacker, and it looked like a six [string] from the front.’

But he turned it sideways, and you could see six other tuning pegs, like a classical guitar, sticking out of the back. I went, "Oh, they kind of condensed the 12-string head into something good-looking.” And it sounded great. I had to get one.

What was the first Rickenbacker 12-string you had after seeing George’s?

I traded an acoustic Gibson 12-string that Bobby Darin had given me because he broke the one that I had before that. I put it up against the piano, and the piano was on casters, and it rolled, and the guitar fell down, and the neck broke off. So he brought me a new Gibson 12-string.

I also traded my five-string banjo — a Vega long-neck five-string banjo, like Pete Seeger played — and some cash, and I bought a Rickenbacker 360 12-string in a guitar store in L.A. I played it for about seven hours a day. [laughs]

Was it tough to get used to the 12-string?

Oh, Jim Dixon, who was our manager, said, “You can’t put a capo on an electric guitar, it’s just not done.” So, I had to learn a lot of scales and learn how to play all kinds of stuff up the neck. I had to practice like seven hours a day to do this. That’s how the “Eight Miles High” thing came about, because I’d been doing a lot of scales.

George influenced you, but if you listen to “If I Needed Someone” from Rubber Soul, it’s obvious that you influenced him, too.

Well, Derek Taylor had been in London, and George gave him, I think, a three-inch reel-to-reel of “If I Needed Someone.” He came over — Derek had been living in L.A., and we were all in Laurel Canyon. He was a few houses down from me, and [Byrds bassist] Chris Hillman.

But Derek came over to my house with this three-inch reel-to-reel tape, and said, “George wants you to play this.” So I played it, and it was “If I Needed Someone.” He said he wants you to know that he got that riff from [Pete Seeger’s] “The Bells of Rhymney” [which the Byrds recorded a famous live version of in 1965].

That same year, in 1965, the Byrds and the Beatles met in August for a psychedelic experience. Can you recount that?

The Beatles had already come over to America and declared that the Byrds were their favorite group. And when they first came over, they would send a limo down to pick us up at our various locations and take us to the house that they were renting up in the Hills, in Beverly Hills.

It was the estate of actress Zsa Zsa Gabor that they had rented for, like, a week, or however long they were there for. And so, we’re coming up in the limo, and there’s all these girls, and they’re up on the fences, and there were policemen, and they took us in. The gate opened up, and we go down to this house, and that’s when we all dropped acid.

What was that like?

Peter Fonda was with us, Ringo [Starr] took acid, and Paul [McCartney] didn’t want to do it. So, George, John, and I did, and Ringo, I think, was playing with some girls in the pool.

Did Paul say why he didn’t want to drop acid, too?

No. I really didn’t have any interaction with Paul at that time. I did when we first met the Beatles in London. It was during that tour that we went over, and they billed us as “America’s answer to the Beatles.” Derek Taylor was with us, and, of course, he had been their press officer, so he introduced us to the Beatles.

I met George and John the first night, and then Paul invited me to the Scotch of St. James, his private club. We had a Scotch and Coke, went outside, and he got into his Aston Martin DB5, and we drove around London. It was really cool.

And later on, we went to a party with the Beatles and the [Rolling] Stones. The Stones told us how their butler would roll up hash joints and put them on the steps for breakfast every morning. [laughs]

Circling back to dropping acid in Beverly Hills, that’s also when you and David Crosby introduced George and John to Ravi Shankar, right?

George, John, David Crosby and I went into this big shower, like a big, maybe nine-foot-square shower, where you could sit on a ledge. And we had one guitar that we kept passing around, and that’s when we showed him some Ravi Shankar stuff — and we all were on acid.

That was especially impactful on George.

George started freaking out. [laughs] He said, “I feel like I’m dying…” And then, Peter Fonda said, “Oh, I know what it’s like to be dead.” And John Lennon said, “Oh, don’t tell me that… you’re creeping me out. This is terrible.”

George was pretty into Indian music by then, so it’s surprising that he hadn’t heard of Ravi Shankar.

Well, Jim Dixon was a producer and engineer at World Pacific Records in Hollywood, and they had Ravi Shankar as one of their artists. So we got a preview of the recordings of Ravi, and we knew about Ravi early on. That’s how we were able to tell George about him, and that he’d been an influence. He had been exposed to Indian music prior to that, but I guess he just didn’t know about Ravi Shankar.

You mentioned earlier that when you went to London, the Byrds were billed as “America’s answer to the Beatles.” But given how you fed off each other, it’s clear that it wasn’t so much about an answer as it was a call-and-response.

Well, what was going on was that America was blindsided by the British Invasion. They were looking for some kind of counter to it. I remember watching American Bandstand, and Dick Clark said, “The best Beatles antidote? It’s probably the Beau Brummels.”

And then, he’s on the phone with somebody, saying, “What? The Byrds? Oh, yeah, okay.

“It’s the Byrds.”

Andrew Daly is an iced-coffee-addicted, oddball Telecaster-playing, alfredo pasta-loving journalist from Long Island, NY, who, in addition to being a contributing writer for Guitar World, scribes for Rock Candy, Bass Player, Total Guitar, and Classic Rock History. Andrew has interviewed favorites like Ace Frehley, Johnny Marr, Vito Bratta, Bruce Kulick, Joe Perry, Brad Whitford, Rich Robinson, and Paul Stanley, while his all-time favorite (rhythm player), Keith Richards, continues to elude him.