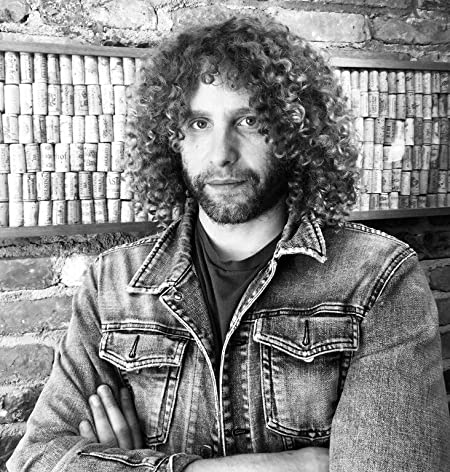

“The Essence of the Song Is Not Just the Notes but the Space Between Those Notes”: Devendra Banhart Talks Songwriting and the Importance of Silence

“The guitar is terrain for endless exploration,” says the Venezuelan-American maestro

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

***The following appeared in the February 2020 issue of Guitar Player***

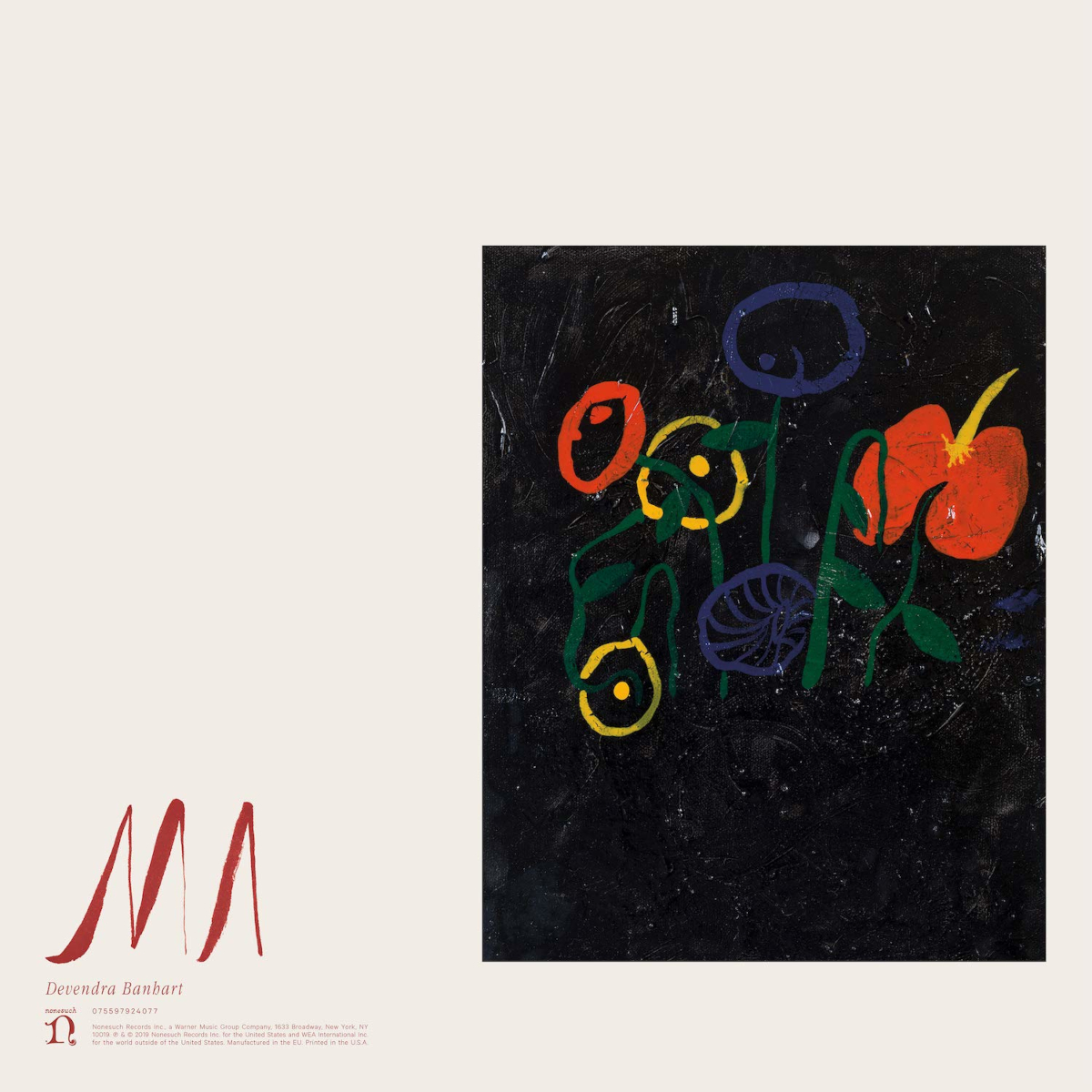

Devendra Banhart gave his 2019 album from Nonesuch Records the title Ma, and true to that word, the subject matter on the record is largely concerned with the ties that bind people to one another and to the world at large, be they maternal, spiritual, cultural or geographical.

However, Banhart says there was another, more specifically musical motivation behind his choosing that title.

The essence of the song is not just the notes but the space between those notes

Devendra Banhart

“Right before we began recording, I was in Japan and I came across this word, ma, a philosophical term for essence, or space,” he explains. “The example for ma is an empty cup, and the essence of that cup is the empty space.

“So I began thinking about that in the context of music. The essence of the song is not just the notes but the space between those notes. And space is so hard to achieve musically for me. I just want to fill it up!” He laughs.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“So I had this word, and it felt like it really worked well as a title. And it happened to be the appropriate word for a record that was so much about maternity, but it also was so appropriate for what I wanted to achieve musically.”

What Banhart achieves musically on Ma is, in fact, quite impressive. The record’s 13 songs are adorned with all manner of synthesizers and saxophones and strings, not to mention wind and percussion instruments and even the sound of the Pacific Ocean.

And yet, despite the rich instrumental tapestry, there’s also plenty of ma to be found in the mix (even if Banhart, as he tells Guitar Player, tends to disagree).

There’s no actual destination with playing the guitar

Devendra Banhart

At the center of it all are Banhart’s hushed, conversational vocals and deft acoustic nylon-string and electric guitar work, which display the influence of a lifetime immersed in the sounds of Delta blues, traditional British folk, Brazilian tropicália, American primitive and other folk styles.

On Ma, the U.S.-born, Venezuelan-raised guitarist continues to weave those diverse influences into a style that is distinctly his own. And though this is Banhart’s 10th studio album overall, he sees this endeavor as a journey with no end.

“There’s no actual destination with playing the guitar,” he says. “There’s no, ‘Oh, I’ve arrived at mastering the guitar!’ It doesn’t work that way. It’s an ongoing practice. And I think that kind of humbles you, like, ‘Wow, there’s so much to this thing!’ The guitar is terrain for endless exploration.”

When you begin the process of writing and recording a new album, is it with a clear idea in mind of what you’re looking to achieve? Or do you tend to write words and music as the inspiration hits?

It works more like I’m accumulating material. I’m kind of collecting fragments and rubble, and odds and ends. And then at some point I reach for the notebook and start to contribute to this slow trickle of accumulation.

I start to write things down, and it’s very slow at first. But then it becomes a daily practice, and eventually I’ve got quite a few notebooks full. So at that point I dive into it and ask, “What’s here? What is this story about?”

I start to write things down, and it’s very slow at first. But then it becomes a daily practice, and eventually I’ve got quite a few notebooks full

Devendra Banhart

So what is the story about?

For a long time now, I’ve been surrounded by my chosen family, people I’ve known since they were kids and who now have kids, and I’m now like an auntie to their kids. I’m observing my friends in a new way when I’m seeing the relationship between them and their children, and it’s a beautiful relationship. And then I’m coming home to write about that. I’m seeing that in the notebook.

Then, at the same time, I’m seeing Venezuela, the country I grew up in, totally on fire. Literally. I’m seeing an apocalypse. I’m seeing a mass exodus of over 2,000 people a day trying to leave the country that I grew up in, and it’s a country I cannot disassociate from my own mother. And actually, while we’re talking right now, it’s still happening.

So I’m seeing that in the notebooks. And then I’m also seeing that when I’m feeling that sort of frightened and insecure and heartbroken feeling, and experiencing that kind of struggle, I’m still listening to the same music I always have.

I’m still listening to Vashti Bunyan and Bert Jansch and Davey Graham and Nick Drake and Carole King and Joni Mitchell and Leonard Cohen. I still turn to that music for comfort. That’s amazing to me.

Also, I did a tour of Asia and spent a lot of time in Japan, and all of those things make it into the materials that make up the album as well.

Early in your career, your music was centered around just acoustic guitar and vocal, but you’ve expanded your range of instrumentation considerably since then. These days, what role does the guitar play in your writing and recording?

I was really going for this, like, 'guitar world,' where what I have is my guitar and it’s kind of all I need

Devendra Banhart

Well, in the beginning I was obsessed with Mississippi John Hurt. And I thought, Okay, this is it. This is the kind of guitar playing I want to play.

But then at the same time I also became really obsessed with Brazilian guitarists – Luiz Bonfá, Antônio Carlos Jobim, João Gilberto, Jorge Ben and, of course, Caetano Veloso. I just really loved them.

And then it led to this kind of British folk thing where I’m obsessed with Davey Graham, Nick Drake, John Martyn, Bert Jansch and John Renbourn, and then the American kind of counterparts like John Fahey, Leo Kottke and Tim Hardin.

That’s not really answering your question, but the point is that I was really going for this, like, “guitar world,” where what I have is my guitar and it’s kind of all I need. Then things began to expand, and I had access to other instruments, and we kind of went nuts with that. I realized, Wow, this is a whole world. The records can be more orchestrated and there can be a lot of different instruments. But throughout every single record, it all begins with just me and an acoustic guitar.

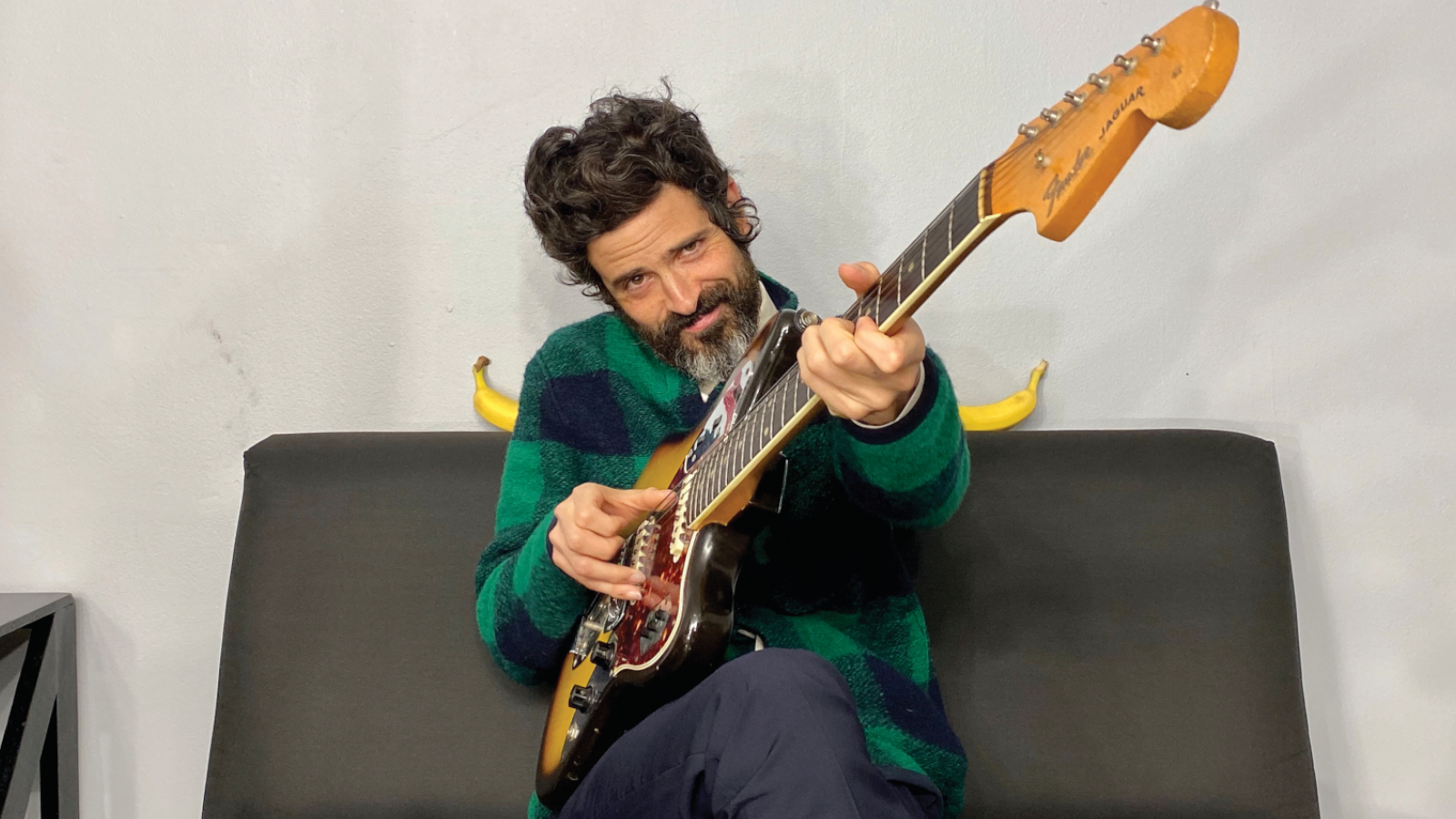

What were your primary guitars on Ma?

I used a Hofner flamenco guitar for all of the nylon-string playing, and I had my mid-’60s [Fender] Jaguar that I used for all of the electric parts. And I had two amps: a small Danelectro DM10 and a Magnatone Varsity Deluxe.

Where did you record the album?

Well, we started at Honen-in, a temple in Kyoto, which is obviously not a recording studio. But we had one hour there, and then we continued in Northern California.

I used a Hofner flamenco guitar for all of the nylon-string playing, and I had my mid-’60s Jaguar that I used for all of the electric parts

Devendra Banhart

How did you wind up recording for one hour in a temple in Kyoto?

It was a total fluke. A friend of mine is the professor of calligraphy at Kyoto University, and she was telling me how she was hanging out with the monks that day, showing them calligraphy. And I said, “Can you ask the head monk if we can record at the temple?” I’m just kidding, basically. And she goes, “Sure, I’ll ask.”

And then she gets back to me and Noah [Georgeson, producer] while we’re on tour in China and says, “You guys have an hour.” And we had already been to Honen-in. We know that temple. It’s an incredible space. It’s one of the oldest Zen Buddhist temples in Kyoto, which is, of course, known for its temples.

We recorded in the Zendo, where you sit, and it was just the best. We recorded this song that didn’t make it on the record, but it helped us realize what we wanted to capture on the album, because there were no walls in the Zendo. There’s the ceiling and, of course, the floor. It’s just a garden. So the distinction between inner and outer is gone.

We wanted to approximate that at home as well. We needed to be in the country, and so we recorded a lot of the record in Big Sur and Stinson Beach [California]. And the first thing we did was open all the windows and record the Pacific Ocean for 24 hours. And that’s in every song, although it’s only audible on “October 12.” You can hear a little bit of it.

There is a strong element of “seeking” in your words and music. You’re always looking for new sounds and unique recording spaces and fresh lyric concepts. Do you feel driven by any artistic muse?

Loren MazzaCane Connors [a.k.a. Guitar Roberts] is my favorite guitar player... He’s playing the silence as much as he’s playing the notes

Devendra Banhart

Well, on this album it was something that I failed to get close to. Something I failed to manifest. But I failed to do it in a way that I’m satisfied with. And that’s the idea of space that is, ironically, in the title of the record.

Loren MazzaCane Connors [a.k.a. Guitar Roberts] is my favorite guitar player, and he really creates space with his playing. It’s so beautiful watching or listening to him play guitar. There’s a sense that he is not even playing the instrument. There’s no object and subject. There’s no guitar and guitarist. It’s just like that temple: There’s no real division between the outside and the inside. It’s just a part of him, and he’s playing the silence as much as he’s playing the notes.

That’s ma.

I did not achieve that space, but that’s something that I’m still striving for. So thank you for reminding me of what a failure everything I’ve done is!

Order Devendra Banhart's latest solo album, Ma, here.

Rich is the co-author of the best-selling Nöthin' But a Good Time: The Uncensored History of the '80s Hard Rock Explosion. He is also a recording and performing musician, and a former editor of Guitar World magazine and executive editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine. He has authored several additional books, among them Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck, the companion to the documentary of the same name.