“Every time I listened to myself after that I’d think, Oh no, everything’s out of tune.” How Steve Vai’s compliment made Andy Timmons paranoid about his tuning

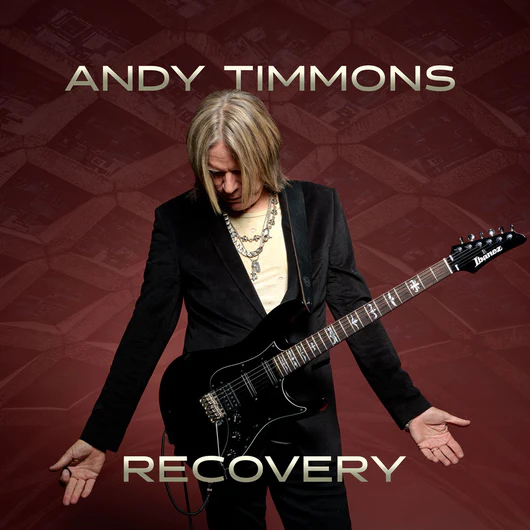

As he releases his new album, 'Recovery,' he talks about gear, Jeff Beck and why you don't need to know every scale and mode

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

There’s something particularly brave about crafting instrumental guitar albums. With no lyrics to lean on, the guitar is left to do nearly all the emotional heavy lifting.

Luckily for Andy Timmons, that’s never been a problem. He only plays when he has something to say. And on his latest album, Recovery, his phrasing on his signature Ibanez electric guitars speaks louder than ever.

Speaking with Guitar Player, Timmons discusses what may be his most emotionally resonant work yet. He reflects on the influence of Jeff Beck — how he "never repeated himself" and kept evolving — and how that mindset helped inspire the album’s opening tribute.

The former Danger Danger guitarist also shares how, growing up, music and melody became his voice, why you should trust your ears more than a tuner when it comes to pitch, and how a well-meaning compliment from Steve Vai left him thinking, Oh no, everything’s out of tune!

Congratulations on Recovery, Andy — such a powerful record and an emotional rollercoaster for the listener. Was it much the same for you during the writing process?

Well, thank you, man. A lot of this material is very personal. Most of my tunes start by reflecting on what’s going on in my life — or in the world.

Sometimes songs can just be songs, and in the instrumental world, you come up with a name that evokes the mood. But there are quite a few pieces on here that are deeply personal.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

"Elegy for Jeff" is an obvious tribute to our hero, Jeff Beck. But tracks like "Recovery," "Why Must It Be So," "Where Did You Go," and "Arizona Sunset" all carry deep meaning for me.

What I love about instrumental music is that once I release a tune — no matter how personal it is — the listener can take from it what they need.

That’s the gratifying part: hearing that a piece of music meant something to someone, depending on where they were in life or what they were going through. If it helps in any small way, that’s my measure of success.

The new album is packed with melodies and phrasing that feel deeply heartfelt. What, for you, is the key to connecting emotionally with your instrument?

I wish I had a specific pathway — like, “Here’s how you do it.” But really, it’s just been a long journey of looking back and asking, “How did I get here?”

From a very young age, music was my outlet. I was a very shy kid, and once I started playing guitar, it became my safe space. From there, it’s been a pursuit of improvement — getting to the point where the instrument isn’t in the way, but just a delivery device. Ideally, there’s no middleman between your emotion and the sound.

People ask, “What’s going through your mind when you play or record?” And in the best-case scenario — nothing. That might sound strange, but it’s almost meditative. The biggest obstacle is usually our own mind: insecurities, distractions, technical frustrations. But when all of that fades away, that’s when something deeper can happen — if everyone’s antennae are tuned in.

With every note you play, there’s always a sense of rhythm in your phrasing. Is time feel something you still consciously work on?

Yeah — time is one of the most primal, foundational elements. The players I’ve gravitated toward in my life, I’ve come to realize, all had amazing time. It’s not just about accuracy — it’s about intention. Placing a note just so, with purpose. You feel that time in your body.

When a musician’s internal clock is that strong, they can bend or place notes in a way that creates emotional weight.

Would you say your note choices are more about what you’re hearing in your head rather than analyzing theory in real time?

That’s a great question — because I’m analyzing it now in hindsight. But when I’m actually playing, it’s all about instinct. It’s about hearing something I want to hear and chasing that.

My love of jazz really helped train my ear. Sure, I can analyze something and say, “This fits in C major,” but when I’m writing or improvising, I’m more focused on what the melody note is doing over the chord. Is it a chord tone? Adding tension? A release? That’s the real magic — tension and release. Simple, but essential.

Your pitch control and note coloring are such a distinctive part of your playing. With today’s obsession with autotune, do you think it robs some modern music of its human character?

Pitch is incredibly important to me. I’m very sensitive to it. Sometimes I’ll intentionally push a note slightly sharp, because there are micro spaces between notes that can be incredibly expressive.

Steve Vai said he thought I was really in tune. That meant a lot — but it also made me even more insecure."

— Andy Timmons

The guitar is imperfect. There are all kinds of systems that try to “fix” tuning issues, but at the end of the day, it’s your fingers and your ears that make it work.

You learn to intonate, you set up your instrument well — but from there, it’s all about touch.

teve Vai actually said to me the last time I saw him that he thought I was really in tune. That meant a lot — but it also made me even more insecure. Every time I listened to myself after that I’d think, “Oh no, everything’s out of tune — I’ve got to be better.”

With guys like Tommy Emmanuel and other great players, there’s a lot of compensation going on in their hands within chords and single notes. Even Jeff Beck: If you took his guitar and strummed it without him holding it, it was probably wildly out of tune. But he knew how to fight it — how to get it to pitch. He was brilliant at that.

That’s the connection — a great ear, and an understanding of the guitar’s limitations, and the compensations that have to be made even within a chord.

There’s a piece I play called “The Prayer and the Answer,” and I know I’m greatly sharpening the third of that chord right there. I’m not doing it just to do it — even if the tuner says the guitar is in tune, well, it’s not in tune. But my fingers get it there.

Speaking of Jeff Beck, there’s a powerful tribute to him on Recovery. Could you tell us more about his impact on your musical identity?

Absolutely. I’ve been lucky to have Jeff Beck’s music in my life since I was a little kid. My older brother Mark was buying all the British Invasion records — the Beatles, the Yardbirds. I remember The Yardbirds Greatest Hits being in the house. “Shapes of Things” really stuck with me. It’s this great pop song with a wild, feedback-laden solo. That was Jeff, probably on his Esquire, cranked and howling. Even if that had been the only thing he ever did, he’d still be one of the all-time greats.

But then he forms the Jeff Beck Group with Rod Stewart and Ron Wood, basically laying the groundwork for what Led Zeppelin would become. Then comes the fusion era with Jan Hammer, and later Guitar Shop with “Where Were You” — an absolute game changer.

He just kept evolving. Later, he worked with Jennifer Batten, and then Emotion & Commotion — those tracks like “Nessun Dorma” or “Corpus Christi Carol” are just incredible. So sensitive. So expressive.

Jeff refused to coast — he never repeated himself and was always evolving. That’s what I aspire to: to keep getting better.

— Andy Timmons

You look at his contemporaries — Clapton, Page — amazing, iconic players. But whether they kept advancing is another story. Jeff refused to coast — he never repeated himself and was always evolving. That’s what I aspire to: to keep getting better.

Honestly, even though I always appreciated Jeff, he actually wasn’t a huge influence on me early on. I was more drawn to guys with a bit more polish — like Steve Lukather, Larry Carlton, Robben Ford, Mike Stern. But when I saw Jeff live in the late ’90s, it really hit me. I started diving back into his catalog and realized how deeply he was pushing the instrument forward. He became one of those obsessions.

Did you ever get the chance to play with him?

No, we never played together, unfortunately. But I did meet him several times. He was always kind, humble and gracious. He even signed my Wired album.

I don’t think he ever heard my playing, at least not that I know of. But that wasn’t the point — I just wanted to tell him what he meant to me. That’s why it felt right to open Recovery with a tribute. Not to imitate him, but to offer a little of that spirit.

Talk us through the gear you used on Recovery.

I used a combination of amps and guitars, but at the heart of it all is my AT100 — my longtime main guitar, which just celebrated its 31st birthday. It’s truly my “security blanket,” and it handled the majority of the recording.

That said, I also used the newer ATZ300 for certain tracks and sections. It has a mahogany body with a rosewood fingerboard and DiMarzio pickups. Unlike the original version, where the pickups were mounted directly into the body, these are pickguard-mounted. Tonally, it sits somewhere between the AT100 and the older AT300, and I’ve really enjoyed using it both in the studio and on tour.

Amp-wise, I ran a mix of Mesa/Boogie Lone Stars, a Suhr SL68, and a genuine 1968 Marshall “Plexi.” Most of the time, I kept the amps fairly clean and shaped the sound with pedals.

For drive tones, I leaned heavily on the Keeley Mark III Driver — a pedal we spent a lot of time refining. My Keeley Halo Dual Echo was pretty much always on, running in stereo on the dotted eighth/quarter setting with modulation, and controlled via an expression pedal for real-time dynamics.

I’ve had students say, 'I need to know every scale and every mode,' and I always tell them, 'No, you don’t.'”

— Andy Timmons

When I needed a more saturated lead tone, I’d run a JHS distortion into the front of the Marshall. Sometimes I’d stack another Keeley Mark III — set to germanium — in front of that to subtly carve out low end, which helped balance things out when switching from the bridge to the neck pickup.

All effects were run into the front of the amps — no loops. I like the immediacy of that setup. It gave me the range and nuance I needed to really capture the emotional arc of the record.

Circling back to playing, was there a lightning-bolt moment for you in terms of how you visualize the fretboard?

I tend to play across the neck more than vertically, and that was a bit of an epiphany for me — realizing that you don’t have to stay boxed into a position.

laying pentatonics across different positions really opened things up. I started seeing how they related to chord shapes, even subconsciously. Knowing where the chord tones are — like where the thirds, roots, or sevenths live — gives you so much expressive power.

The challenge with guitar is that there are multiple places to play the same note. But once you know where the home base is — like all the A’s on the fretboard — everything else can orbit around that.

If you were starting again on the guitar today, would you approach anything differently?

The cool thing about starting today is that you’ve got the whole musical universe in your pocket. But that can also be overwhelming. I’ve had students say, “I need to know every scale and every mode,” and I always tell them, “No, you don’t.”

I learned everything by ear because I loved it. That’s the most important thing — stay connected to the music you love. Sure, build your theory knowledge and fretboard awareness, but do it in steps. Don’t lose the joy of playing.

Make music at every point in the journey. If you love it enough, you’ll keep going.

The Editor in chief of Guitar Interactive since 2017, Jonathan has written online articles for Guitar World, Guitar Player and Guitar Aficionado over the last decade. He has interviewed hundreds of music's finest, including Slash, Joe Satriani, Kirk Hammett and Steve Vai, to name a few. Jonathan's not a bad player either, occasionally doing gear reviews, session work and online lessons for Lick Library.