“I’d Lost My Girl, Hendrix Had Come and Smeared Everybody Across the Floor… It Wasn’t Looking Too Rosy”: In 1968, Jeff Beck Found Success on His Own Terms With His Own Group

But life after the Yardbirds would prove infinitely harder

If Jeff Beck was aimless after the Yardbirds, there was one man who was willing to point him in a particular direction.

Mickie Most was a producer and manager who, by the dawn of 1967, had scored hits with the Animals (“House of the Rising Sun”), Herman’s Hermits (“I’m Into Something Good”) and Donovan (“Sunshine Superman”).

Beck’s impact on the Yardbirds hadn’t gone unnoticed by Most, and he quickly set about signing the guitarist with an eye toward turning him into a pop star. It was in this guise that Beck released his first solo records “Hi Ho Silver Lining” and “Tallyman,” which reached number 14 and 30, respectively, in the U.K. mid-year.

Beck’s impact on the Yardbirds hadn’t gone unnoticed

He followed them up with an instrumental version of “Love Is Blue,” a song that had been an entry in the 1967 Eurovision Song Contest before going on to become one of the biggest hit singles of the year for Vicky Leandros. Released on February 16, 1968, Beck’s version scored a respectable 23 on the charts.

But the guitarist had little stomach for becoming a pop star. Eric Clapton, his predecessor in the Yardbirds, was turning rock on its head with Cream, while his successor, Jimmy Page, was revving up the Yardbirds into a hard rock act that would soon become Led Zeppelin.

Meanwhile, no one could touch Jimi Hendrix.

Even as he recorded “Love Is Blue,” Beck had begun putting together a group of his own. He’d already found his lead vocalist, Rod Stewart, who’d performed with Long John Baldry and keyboardist Brian Auger in Steampacket, a British blues band put together by Yardbirds manager Giorgio Gomelsky.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Stewart had contributed backing vocals to “Tallyman” and sang lead on its flipside, “Rock My Plimsoul.” Beck recalled his decisive meeting with Rod the Mod to Total Guitar in 2016. “Let’s not beat around the bush, I was pretty down at the time,” he said. “I’d lost my girl, Hendrix had come and smeared everybody across the floor… it wasn’t looking too rosy.

Let’s not beat around the bush, I was pretty down at the time

Jeff Beck

“I’d fallen out with the Yardbirds – whatever happened, I was out, and I’m facing a Monday morning just outside London thinking, What’s the point? It’s all gone against me. So I went to the Cromwell Inn, which was my last hope of preventing anything silly happening.”

Taking his seat, he noticed “a bloke in the corner” slumped over his beer. It was Rod. After leaving Steampacket, he’d joined Shotgun Express in 1966, a blues outfit formed by Peter Green and Mick Fleetwood, but it failed to have any measure of success.

With Beck, however, Stewart would finally get the notice he deserved.

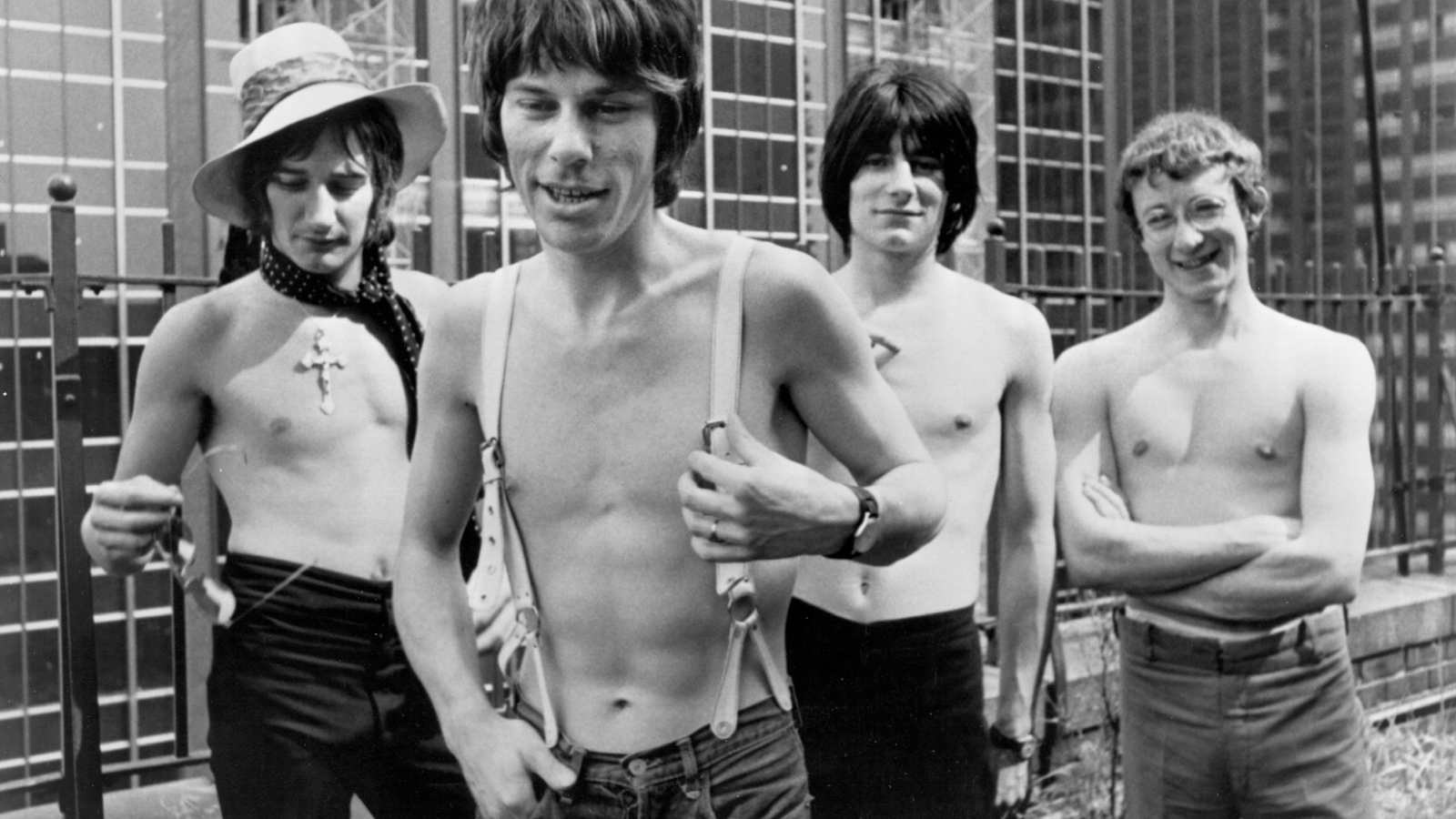

Beck also signed up Ron Wood as second guitarist, and former Brian Auger bassist Dave Ambrose. “Jeff couldn’t take him, though, so he asked me, ‘Would you mind switching to bass?’” Wood explained to Guitar World in March 1985. “And I said, ‘Nothing could suit me better because I’m so stagnant on guitar at the moment that I’ve really run out of direction.’”

After working with a number of drummers, including Clem Cattini and Aynsley Dunbar, Beck settled on Micky Waller, a pal of Stewart’s from Steampacket.

It was this lineup that toured the U.S. in early 1968 at the recommendation of future Zeppelin manager Peter Grant. The group went over so well that Grant was able to secure them a contract with Epic Records, which released the Jeff Beck Group’s debut, Truth, that July.The album was an instant hit, reaching number 15 on the U.S. charts.

They took a heavier direction on their next album, 1969’s 'Beck-Ola'

They took a heavier direction on their next album, 1969’s Beck-Ola, which saw Waller replaced by Tony Newman. Like its predecessor, Beck-Ola went to number 15 after its release that June, but already, the Jeff Beck Group was breaking up. Beck had fired Wood for complaining too much. Stewart, who’d grown close to Wood, no longer found touring fun without him.

In July, Stewart, Wood and Waller regrouped in the studio to record the singer’s debut album, An Old Raincoat Won’t Ever Let You Down.

The Jeff Beck Group was scheduled to perform at Woodstock, but Beck pulled the plug. “I didn’t think we could have pulled it off,” he told Guitar Player in 2003. “I just didn’t think we were big-stage material, and I couldn’t bear to be preserved on film playing out of my depth, and having Rod hating the sight of me on screen. Screw that!”

Stewart had his own reasons. “It was a great band to sing with,” he would say of the Jeff Beck Group, “but I couldn’t take all the aggravation and unfriendliness that developed.”

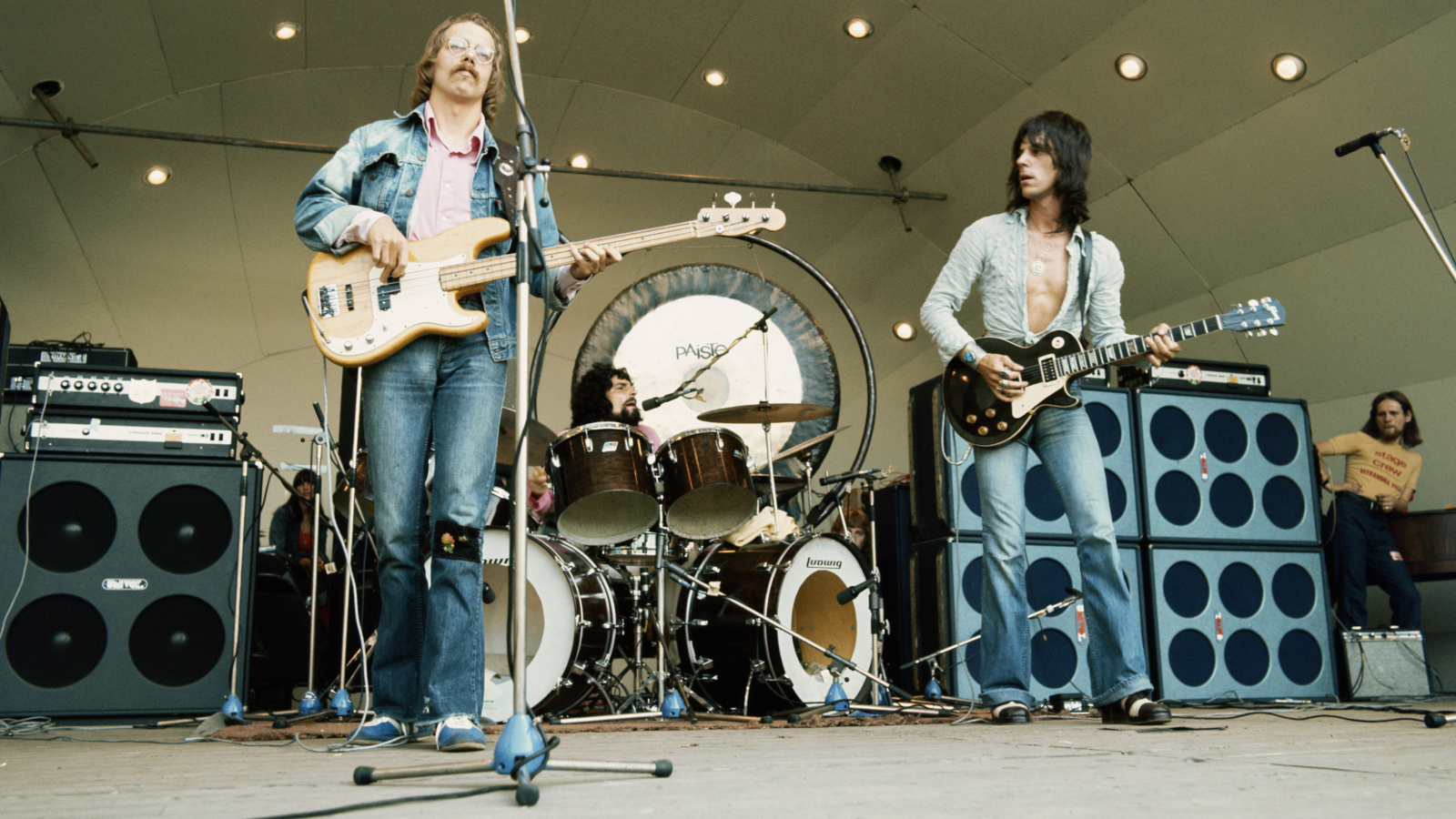

The guitarist re-assembled a new Jeff Beck Group for his next effort. Released in October 1971, Rough and Ready featured Beck with singer/rhythm guitarist Bobby Tench, bassist Clive Chaman, keyboardist Max Middleton and drummer Cozy Powell.

While critics lauded Beck’s guitar work, the songs and Tench’s vocals were considered weak. The band’s self-titled follow-up fared no better despite the involvement of Steve Cropper, one of Beck’s influences, as producer.

In July 1969, Beck was planning to replace his bandmates with bassist Tim Bogert and drummer Carmine Appice

It was here that fate presented Beck with a second chance.

In July 1969, while the first incarnation of the Jeff Beck Group was dissolving, he was planning to replace his bandmates with bassist Tim Bogert and drummer Carmine Appice, founding members of Vanilla Fudge, whom he’d met in 1967.

It all came to an end on November 12, when Beck crashed his car, suffering a skull fracture that took him out of commission for a year. By the time he recovered, Bogert and Appice had formed the hard rock group Cactus.

But with the original Cactus breaking up in 1972, Beck saw his opportunity to reconnect with Bogert and Appice.

The result was one of rock’s great supergroups, Beck, Bogert & Appice. The guitarist saw the power trio as a way to take his music to a new level. “I was trying to play subtle rock and roll,” he told NME of his earlier music. “That stuff was more suitable for clubs, not big stages. This new group will play much heavier music.”

The trio’s sole, self-titled album, released in 1973, drew more from the funk and fusion world than Beck’s previous recordings, particularly on tracks like “Jizz Whizz” and a version of Stevie Wonder’s “Superstition.” It rose to number 12 on the Billboard charts, an auspicious beginning.

As with the Yardbirds, touring took a toll on Beck’s relations with the band

But as with the Yardbirds, touring took a toll on Beck’s relations with the band. “When the album came out, we started to tour, and the band turned into factions,” Bogert told Classic Rock. “It wasn’t the fun I hoped it was going to be. The thrill of it all had been so wonderful in the beginning, but then there were personality conflicts, and things went downhill quickly.”

It ended backstage before a gig at the Rainbow in London, in January 1974. Beck got in Bogert’s face, and the bassist threw a punch.

The sessions for a new album were abandoned. By May, the group was officially no more.

“Rod Stewart had told me long ago, regarding Jeff: ‘Don’t do it. You’ll do an album or two and then it’ll be over,’” Appice told Classic Rock. “But we didn’t listen to that advice. But that’s what happened. It ended up a mess at the end.”

Christopher Scapelliti is editor-in-chief of GuitarPlayer.com and the former editor of Guitar Player, the world’s longest-running guitar magazine, founded in 1967. In his extensive career, he has authored in-depth interviews with such guitarists as Pete Townshend, Slash, Billy Corgan, Jack White, Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren, and audio professionals including Beatles engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott. He is the co-author of Guitar Aficionado: The Collections: The Most Famous, Rare, and Valuable Guitars in the World, a founding editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine, and a former editor with Guitar World, Guitar for the Practicing Musician and Maximum Guitar. Apart from guitars, he maintains a collection of more than 30 vintage analog synthesizers.