“David Bowie came along one day and said, ‘I’ve got a song I’d like you to record.’” Guitarist Mick Ralphs on how a Bowie song for Mott the Hoople accidentally led to the formation of Bad Company

When Bowie's assistance led Mott the Hoople to fame, Ralphs found success in the glitter-rock world was a dead end

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

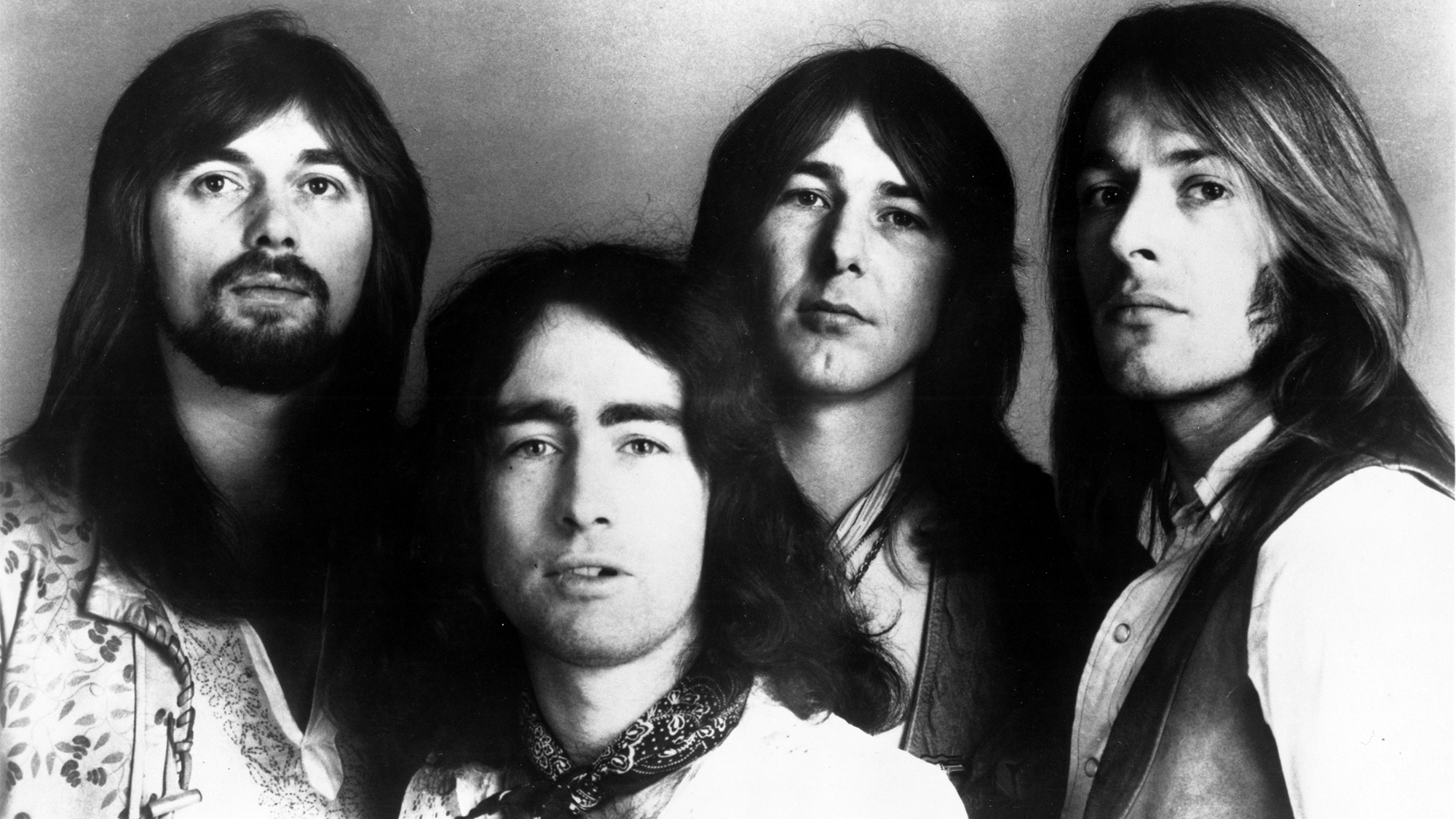

Mick Ralphs had the distinction of playing in two storied rock and roll groups in his lifetime: Mott the Hoople and Bad Company.

In the 1970s, it was impossible to go a day without hearing his bluesy electric guitar playing on the radio, whether in Mott hits like “All the Way From Memphis” and “All the Young Dudes” or Bad Company classics he penned himself, including “Can’t Get Enough,” “Movin’ On” and “Ready For Love.”

Ralphs, who died on June 23 from complications of a 2016 stroke, formed Mott the Hoople in 1969 along with his friends bass guitar player Pete Overend Watts, organist Verden Allen and drummer Dale Griffin.

At the time he’d been playing for just four years, but he was already regarded as an “all-rounder”: the kind of player who can flatpick or strum rhythm at any speed, launch into a rip-roaring slide, and then sear with an emotion-packed solo, pulling out everything from bent blues notes to flashy side-of-the-pick harmonics.

“I went back and got the lads and said, ‘Come on. I know a few people in London; let’s try and get ourselves a deal,’” he recalled in an interview from Guitar Player’s September 1979 issue. “Then through an old friend of mine, [guitarist] Dave Mason, I was introduced to a guy from Island Records.

“To cut a long story short, we got a deal with Island.

"Then Ian Hunter came along and joined the group as the new singer, and we were signed as Mott the Hoople. I stayed with them from ’69 up until late ’73.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Mott were a good band but had difficulty at first breaking into the U.S. market.

“Went through a lot of different styles,” Ralphs said. “We started out playing some of our own songs, some rhythm and blues, and some blues tunes.

“Then our manager-cum-guiding light, Guy Stevens, decided that we should do a Bob Dylan Blonde On Blonde–type thing. I liked the way Robbie Robertson played guitar with Dylan, so I was into that. We had an organ player, so I could play more lead guitar instead of having to keep the rhythm together. Then I’d just sit back and keep the rhythm section together by filling in with chords while the organ player would do his thing. I also started playing the piano a little bit when I joined the group.”

Eventually, though, it began to feel like a grind.

“The group was getting more and more away from what it started out as — a rock and roll band,” Ralphs explained. “It was a good, fun band, like a street band. We never made any money, but we were out there having a hell of a good time, and that was all that mattered.

“But we got to the point where we were disillusioned inasmuch as we were working our asses off and not really getting anywhere. We weren’t on the charts, and we weren’t selling any records. We were just like a cult band.”

They may not have had much success by that point but they had a fan with influence. In 1972, David Bowie was enjoying a career breakthrough with his album The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders From Mars. He had a song he thought would be perfect for Mott the Hoople called “All the Young Dudes.”

When Bowie heard Mott were planning to break up, he offered them the tune, thinking it might be a hit for them.

“David Bowie came along one day and said, ‘Well, don’t break up. I’ve got a song which I’d like you to record, regardless of whether you put it out or not. I just want you to try,’ ” Ralphs recalled.

“It was ‘All the Young Dudes,’ and that was our salvation, really. It was a big hit in England and America, putting the group on the map.”

Bowie not only wrote the song, he produced it and the album of the same name. The next album was even bigger. Titled simply Mott, it was a top 10 record in the U.K. and became the group’s best seller in the U.S., helped along by the singles “Honaloochie Boogie and “All the Way From Memphis.”

But for Ralphs, the writing was on the wall. He was dissatisfied with the group’s new status as a glam-rock act.

“We got so closely associated with David Bowie that we couldn’t get away from that,” he said. “It was like we were tagged a glitter group.

“Then in the end I got the feeling that I was just playing guitar. I could have been anybody up there, not necessarily me.”

He was also unhappy about Hunter’s performances on his songs. Mott had included an early version of a tune that would later become famous via Bad Company: “Ready for Love.” In fact, Ralphs had already written other songs that would become hits for Bad Company. But none of them seemed a good fit for Hunter.

“I had songs like ‘Can’t Get Enough’ and ‘Movin’ On,’ which we never used with Mott because Ian Hunter couldn’t sing them,” Ralphs said. “This is not a derogatory remark toward Ian — they were just not his style. He was more into screaming about politics, and I was into singing about being on the road and the usual things blues songs are about, the day-to-day things.

It got to the point where Ian and I were clashing, and I said, ‘Look, you do what you want to do, and I’ll go off and do what I want to do.’ If I met him today, I’m sure I’d get on really well with him, though. It just got to the point where we couldn’t work together anymore.”

In 1973 — at the height of Mott’s success — Ralphs quit and began working on his own blues- and hard rock-based material. He also found the perfect voice for his songs in Paul Rodgers. At the time, Rodgers was well-known for his work with the band Free, especially on the song “All Right Now.”

“I’d known him from Island Records,” Ralphs recalled. “Free had broken up, and he was in a group called Peace, which really wasn’t doing much. So we both sat down and talked about our gripes, and then we tried to get together and trade songs. We finally had a dozen or 15 songs that we had written but weren’t using.”

Borrowing a mobile studio owned by Faces bassist Ronnie Lane, Ralphs and Rodgers began laying down demos, assisted by drummer Simon Kirke, who had also been in Free,

“Paul and I borrowed Ronnie Lane’s mobile studio to lay down some demos,” Ralphs said. “Then Simon Kirke, our drummer, turned up. We asked him to play drums, and he said, ‘Yeah, sure. Nothing else to do.’

Eventually they found Boz Burrell, formerly the bass guitar player for King Crimson, and Bad Company was born.

The name, as it happened, was the title of a new song written by Rodgers. But as Rodgers explained, Ralphs thought it was the perfect name for the group.

“He said, ‘Yes, that's it! That's what we gotta call the band,’” Rodgers recalled.

“And I said, ‘No, it's actually a song, you know, I'm just working on.’ And he said, ‘No, no, we've gotta call the band Bad Company. That's it!’

As the new group began to materialize, they called Peter Green, manager of Led Zeppelin, and asked him to handle their affairs.

“He was definitely interested in what we were doing,” Ralphs said, “and he agreed to work with us. I believe he viewed the group as a fresh challenge.”

Bad Company became the first group to sign with Led Zeppelin’s newly formed Swan Song label, and in November 1973 they recorded their debut LP, Bad Company, using a mobile studio.

The album brought them unexpected success. In addition to the title track, it featured three songs by Ralphs — “Can’t Get Enough,” “Movin’ On,” and a remake of “Ready for Love” — that helped make it a huge seller and led to Bad Company being named the best group of 1974 by numerous polls.

In 1975 they sold out every venue on their second U.S. tour, including Madison Square Garden and the Los Angeles Forum. Their second album, Straight Shooter, was recorded in September 1974; “Feel Like Makin’ Love,” a composition by Ralphs and Rodgers, became a hit single.

Looking back on it all in 1979, Ralphs said, “I’m just very, very grateful. I don’t know how long it will last; it might all be over in two years.

“But it’s good for us at the moment. I’ve got a nice collection of guitars; I’ve got some nice friends, a nice house in England. So I’m pretty happy.”

Bad Company will be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in November.

Christopher Scapelliti is editor-in-chief of GuitarPlayer.com and the former editor of Guitar Player, the world’s longest-running guitar magazine, founded in 1967. In his extensive career, he has authored in-depth interviews with such guitarists as Pete Townshend, Slash, Billy Corgan, Jack White, Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren, and audio professionals including Beatles engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott. He is the co-author of Guitar Aficionado: The Collections: The Most Famous, Rare, and Valuable Guitars in the World, a founding editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine, and a former editor with Guitar World, Guitar for the Practicing Musician and Maximum Guitar. Apart from guitars, he maintains a collection of more than 30 vintage analog synthesizers.