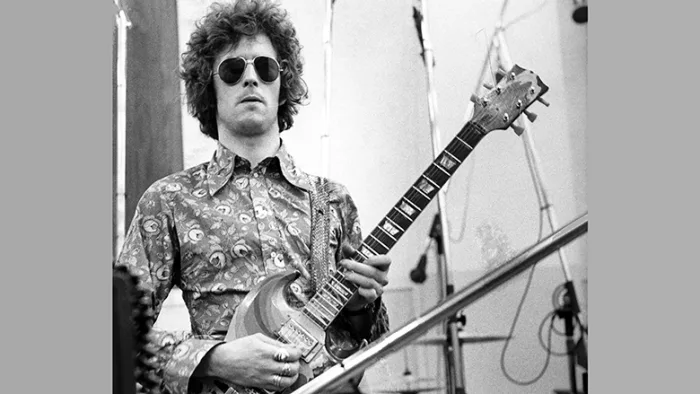

Eric Clapton's Top 10 Cream Riffs

Dig deep into the vault to rediscover 10 of Eric Clapton's most timeless original Cream riffs.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Cream put their unique stamp on many blues covers and always credited the songs’ composers, but it was their original material that blazed new trails and defined the sound of an era, as the band’s blues-laced compositions transmogrified into epic, purple-polka-dot-laden guitar odysseys.

And talk about guitar tones! Remember, this was the dawn of the amplifier as an integral part of the tone chain. Clapton was still primarily a Gibson man, and his vintage Les Paul and SG tones (delivered by overdriven, ambient-miked Marshall and Fender amps) were thick, juicy, and deliciously atmospheric. Studio cohorts Felix Pappalardi and Tom Dowd were among the first U.S. producers and engineers to generate an industry-wide buzz with their sound, and from Eric Johnson to Edward Van Halen, the entire Cream catalog has long served as a benchmark for guitar tone enthusiasts worldwide.

We’ll kick off this historic blast from the past by inducting Cream’s version of Robert Johnson’s “Crossroads” into the Lick Library Hall of Fame, thereby rendering it exempt from the following list.

Now, let’s dig deep into the vault to rediscover 10 timeless original Cream riffs.

10. “Dance the Night Away”

Disraeli Gears (0:00-0:15)

The chimey jangle of this irresistible psych-pop gem reveals that Clapton was as infatuated with West Coast country rockers The Byrds as he was with Chicago blues guitarists during the recording of Disraeli Gears. (Check out his “raga rock” solo later in the track.) On the song’s signature intro riff, Clapton overdubs two electric 12-strings—probably a Fender XII—arpeggiating slightly different Am and identical D/F# voicings an octave apart. Note that the higher octave part (Gtr. 2) lays out until the third repeat. Pay attention to the staccato marks on beat four of bar 2 and dig that magical mushroom vibe.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

9. “N.S.U.”

Fresh Cream (0:04-0:36)

Like a raging rock and roll nursery rhyme, the intro and verse figures on this tune pit Baker’s thunderous toms and Clapton’s partially open-voiced C arpeggios (Gtr. 1) against Bruce’s sly, off-the-beat bass and vocals, making the first two bars of each verse feel like the beat has been turned around. Clever! Choral “whoa”s float dreamily over Clapton’s driving quarter-note power chords (each voiced with the 5 in the bass for extra girth) and syncopated single-note and double-stop overdubs (Gtr. 2). The dramatic cut to A in the second ending precedes a two-bar rest followed by a snare drum cue and pounding V chord (G) that segues to the next verse. To complete the second verse, play bar 1 four times and continue as written until you hit the second ending. Here, substitute a bar of 2/4, then jump back and transpose bars 2 through 6 of the remaining progression (including the repeat) down a minor third to generate D/A-C/G-A-D/A-C/G-F#. Play the rests and last bar as written and you’re there. (Also on Live Cream, Volume I.)

8. “Sleepy Time Time”

Fresh Cream (0:04-0:15)

Clapton’s snaky 12/8 lines converge from opposite directions on this tune, making the track a great example of contrary motion applied in a dreamy, electrified country blues vibe. Gtr.1’s descending motif concentrates on the b7, 6, 5, 4, b3, and 3 (Bb, A, G, F, Eb, and E), while Gtr. 2 doubles the 5-b7-root-based bass line. I’d long assumed that the harmonic intervals formed during beat one in bars 2 and 3 were chromatic tritones that outlined B7-C7, but the first interval is actually a perfect fourth and the second a major third—another tasty twist that reinforces the notion that Cream’s blues often sounded more, well, purple. (Also on Live Cream, Volume I.)

7. “Outside Woman Blues”

Disraeli Gears (0:00-0:17)

Clapton’s legendary “woman tone”—achieved by rolling the treble off of his neck-position humbucker and blasting through an overdriven Marshall—is all over Disraeli Gears and is particularly evident on the response portion of this main riff. In fact, it’s likely that the nickname refers to Clapton’s second guitar overdub (Gtr. 2) on this track. (Gtr.1 doubles this part two octaves lower sans “woman tone.”) My biggest surprise in reexamining the riff was that Clapton played a straight E7 chord in bar 1, not the E7#9 he incorporated into the reunion shows. The first four repeats of bar 1 constitute the intro, and the verse features only two repeats of this figure plus the riff in bars 2 and 3. Repeat this four-bar move, then play two bars of a B7#9 V chord followed by the response riff to complete the 12-bar progression.

6. “Politician”

Goodbye (0:00-0:21)

Interestingly, this elephantine blues riff began its life in a slightly different form. An early recording (documented on BBC Sessions) contains an altered version in which the b3-3 move on beat two (F-F#) is replaced by the 3 and 4 (F# and G). Both riffs take the same tact, approaching key chord tones from their lower chromatic neighbors, but this now-standard version definitely packs a bigger wallop. The staccato eighth-notes on the and of beats one, two, and four are crucial phrasing elements, so don’t ignore them. (Also on Wheels of Fire and Live Cream, Volume II.)

5. “I Feel Free”

Fresh Cream (1:15-1:47)

Framed in one of the most elaborate productions by Jack Bruce and lyricist Pete Brown, Clapton’s exquisitely composed solo seems atonal at times, but closer inspection reveals it’s actually outlining harmonies a third above the background vocal melody. Study this one carefully: From Clapton’s impeccable vibrato and unusual note choices to his spot-on pre-bends, precise melodic bends and releases, and knack for thematic development, every lick is a lesson in itself. Clapton sticks with his neck-pickup “woman tone” until the very last phrase, where, in a move that’s been making grown men cry for forty years, he switches to the bridge pickup. Gtr. 2 provides another fine example of Clapton’s prototypical power chording, and is clearly a model for Edward Van Halen’s fabled “brown sound.”

4. “Badge”

Goodbye (1:07-1:17)

Perhaps the most tremendous titanium-testicles moment at Cream’s 2005 concerts was when Clapton held an Am7 and basked in up to 16 seconds of uproarious man-cries before launching this signature chordal interlude. Honestly, the collective roar at Madison Square Garden made any other major event held there sound like a little league game. Clapton’s beautiful Leslie swirl sounds downright religious on the original studio recording. The phrase begins mid-measure with an ascending root-position D arpeggio followed by anticipated G/C, G/B, and G arpeggiations that lead back to a full bar of D. The ghosted open D on the downbeat of bar 1 is barely audible. (I once heard a rumor that George Harrison played this part. Hmm.... Any opinions?)

3. “Tales of Brave Ulysses”

Disraeli Gears (0:21-0:30)

This mystical track and its cousin, “White Room” (call it a tie for third place), both utilize D and G5 power chords over a descending D-C-B-Bb bass line that Clapton has admitted borrowing from the Lovin’ Spoonful’s “Summer in the City.” Bruce does alter the bass part to D-F-G-Bb, complete with chromatic passing tones, in the second half of the verse, but the only major difference in the “White Room” verse progression is the Bb5 and C5 chords injected into beats three and four of bar 2. This studio version of “Tales...” also features a single-note wah-wah overdub that doubles the bassline one octave higher, probably on the D string. (Also on Live Cream, Volume II.)

2. “Steppin’ Out”

Live Cream, Volume II (0:15-0:29)

Dating back to his pre-Bluesbreakers days, Clapton initially recorded this signature rave-up instrumental in 1965 with an ad-hoc group called the Powerhouse (featuring Jack Bruce and Steve Winwood) for an album entitled What’s Shakin’ before re-cutting the definitive version with John Mayall later that year. Cream’s frequent live versions of “Steppin’ Out” became an up-tempo tour-de-force for Clapton’s stream-of-consciousness improvisations, which often stretched for fifteen minutes or more. The ingeniously simple head alternates between identically fingered I, V and I figures (G-D-G) played on adjacent string groups, and shifts from straight to swing eighth-note feels every two bars. Follow the D.C al fine indicator back to the top and stop at the fine sign to complete the 12-bar form. (Historians will note that Ritchie Blackmore paraphrased this head in Deep Purple’s “Lazy.”)

1. “Sunshine of Your Love”

Disraeli Gears (0:00-0:17)

It’s fascinating to trace how the number one Cream riff of all time—a pillar of rock radio for over three decades now—evolved over the years at concerts after its initial appearance on Disraeli Gears. The song’s primordial syncopated theme—a twice-repeated single-note riff followed by a chordal version enhanced with raked and heavily vibrated double stops—is notated in bars 1 through 4. For complete authenticity, play the D7-D7-C7-D7 as straight eighth-notes, then add the sixteenth-note slide on the repeat. Variation 1 shows how Clapton eventually fleshed out the descending 5-b5-4 (A-Ab-G) line by adding a pedal D above each note, while Variation 2 incorporates a pair of major-third intervals built from the A and Ab. Both feature different ending phrases in bar 2, which are yours to mix and match at will. Pass it on! (Also on Live Cream, Volume II.)

Guitar Player is the world’s most comprehensive, trusted and insightful guitar publication for passionate guitarists and active musicians of all ages. Guitar Player magazine is published 13 times a year in print and digital formats. The magazine was established in 1967 and is the world's oldest guitar magazine. When "Guitar Player Staff" is credited as the author, it's usually because more than one author on the team has created the story.