“I threw my guitar in the air and kicked all the amps off the stage. Then I staggered off and just collapsed.” Eric Bell on the show that ended his dream-come-true gig as Thin Lizzy’s guitar player

The guitarist says he couldn't play without drinking — and couldn't play after drinking, bringing his time with the Irish rockers to an early end

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

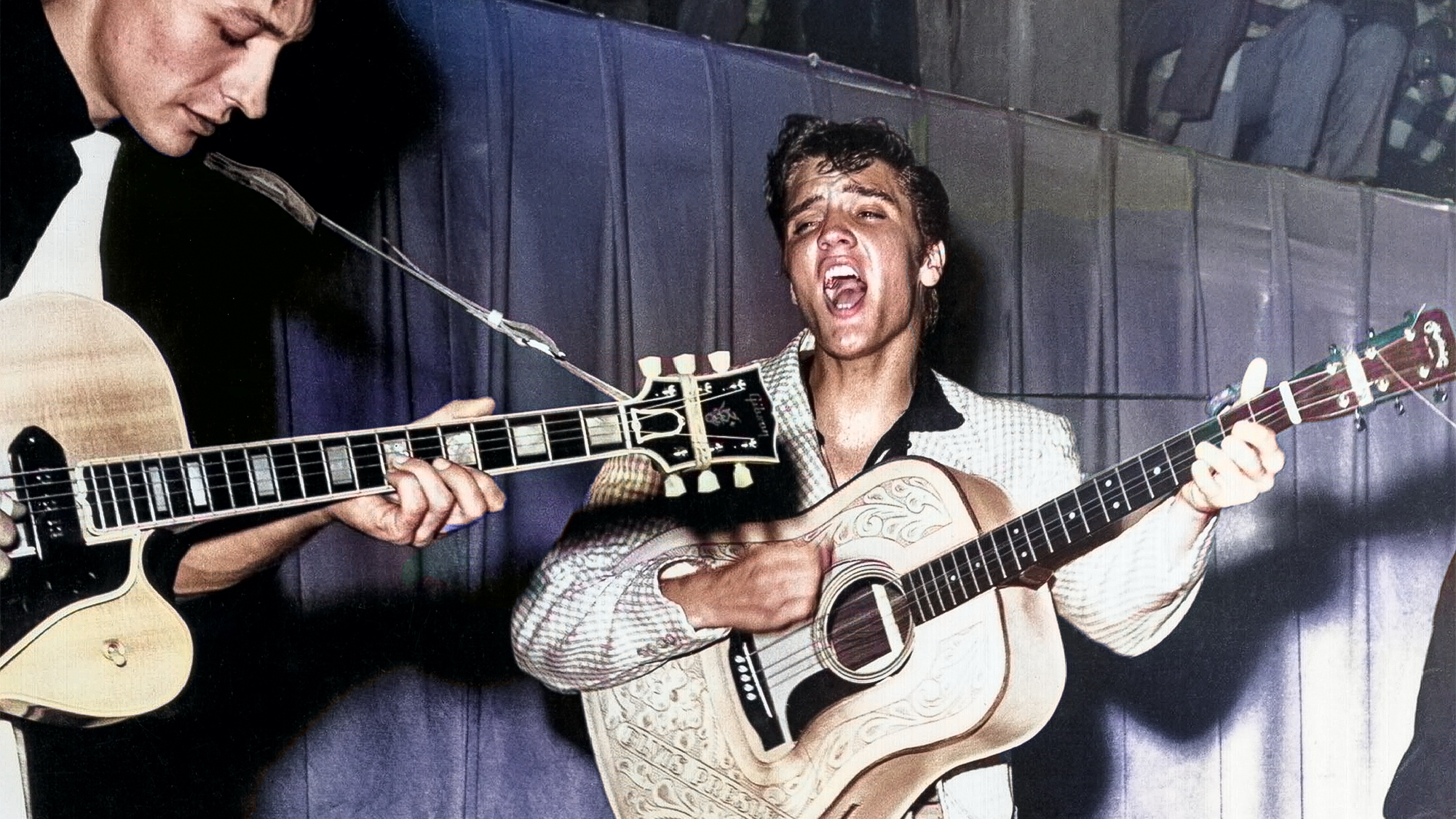

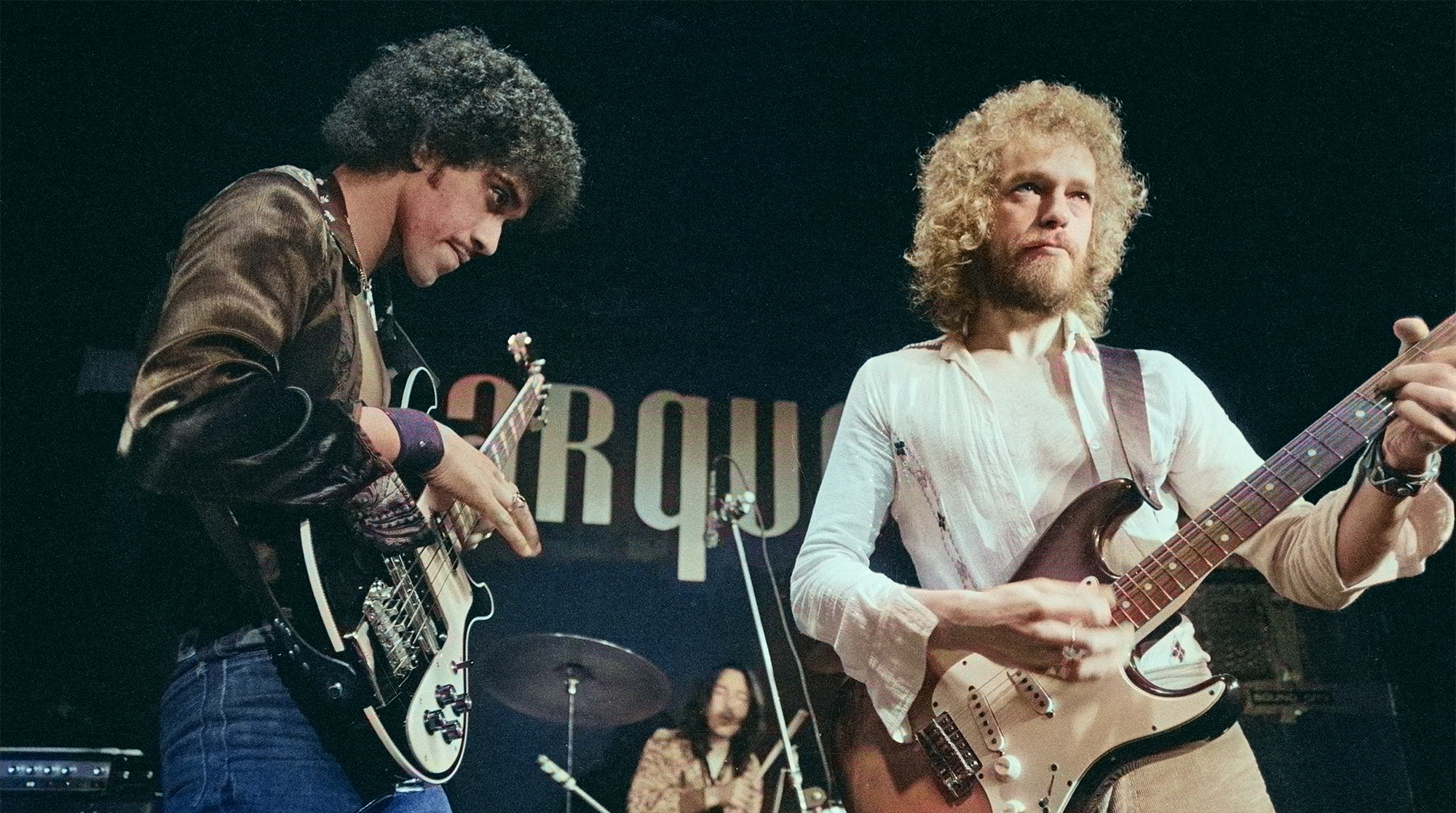

Thin Lizzy should have been everything Irish guitarist Eric Bell had ever wanted. And at first, it was, but by 1973, things had changed.

“At the start, it was fabulous,” Bell tells Guitar Player. “It was my dream, come true. We formed Thin Lizzy, and it was fabulous.

“But we were permanently stoned on hash, there was a lot of Guinness, and then, the drugs appeared, as they did everywhere else around that date and time.”

Bell says that while Thin Lizzy’s collective drug use was heavy, the band had a blast making their first three records: 1971’s Thin Lizzy, 1972’s Shades of a Blue Orphanage and 1973’s Vagabonds of the Western World. The last of these contained Bell’s best-known recording with Lizzy, a cover of “Whiskey in the Jar.”

“It was great,” says Bell, who early this year released Acoustic Sessions, an album that re-imagines songs from the group’s first there albums — including “Whisky in the Jar” — in acoustic guitar arrangements.

“But then I started drinking too much and started smoking some very strong dope — and too much of it.”

Making matters worse, Bell’s “social and family life was starting to fall apart,” leading to him living alone in a grungy attic in London. And it was while the young guitarist was in this state of isolation that his drug and alcohol intake went over the edge.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“It went from bad to worse,” Bell admits. “I remember one night, before a show, I was a nervous wreck. There was a big crowd outside to see us, but there was no dope. I was straight, picked up the guitar.

"And it felt horrible.”

Sadly, Bell had been so high, and so drunk, so often, that performing without substances coursing through his system had become next to impossible.

“I just didn’t feel right,” he says. “Luckily, this guy came in, fired up a joint, and I went over and said, ‘Excuse me, can I have a smoke?’”

After firing up the joint, Bell says that he picked up a guitar and was back to his old self. “All of a sudden, I’m Eric Clapton,” he says with a laugh.

“But then I thought, Eric, you’ve got a problem here, man. You can’t play when you’re straight.”

Making matters worse, Lizzy’s touring schedule was relentless, and Bell says management didn’t care much about his well-being.

“I started losing the plot,” he says. “I needed to come off the road for a few weeks, but management wasn’t having it.”

Even if Lizzy’s management did check Bell into rehab, the guitarist's issues were so out of control by then, it might not have made a difference.

“After gigs would finish, I’d be talking to myself,” he says. “I’d say, ‘After this gig, have one drink, pack up, go back to the hotel, and have a fucking sleep.'”

But Bell couldn’t do it.

“That was the idea,” he says. “But after the last song, the whiskey comes out, and the party starts again. The booze and the dope came out, and I’d think, Yeah, here we are again. I couldn’t stop. And it got worse and worse.”

Bell’s habits came to a head during an infamous gig in 1973, on New Year’s Eve, in Belfast, at Queen's University.

“I got to the gig early, and there was nobody there,” he recalls. “I went into the changing room, and there was just this table with every alcoholic drink that’s ever been discovered.”

Upon seeing this smorgasbord of Devil’s Delight, Bell began to sweat.

“I’m sitting there going, ‘My God… for fucks sake, keep it together,’” he says. “So I had one small whiskey, and a draft of Guinness, and so on…

“By the time I got onstage, I was blitzed. I was just completely, utterly blitzed.”

The members of Thin Lizzy were no strangers to performing under the influence, and Bell, especially, was a seasoned drinker. Even so, on this particular evening, the guitarist was in rare form.

“I didn’t know where I was,” he says. “I didn’t know what I was doing. I surely should have cancelled the gig.”

But the show went on, and after strapping on his Stratocaster, Bell says, things went from bad to worse.

“We played three songs,” he recalls. “And the whole time, there’s a voice in my head, saying, ‘Eric, you gotta get out of here, man. You went a step too far. You need to be taken to a clinic and stay there for two or three weeks.’”

The idea of a musician being so far gone onstage while fans urge him on to provide them with a good time is harrowing. But Bell’s feeling of helplessness paints an even darker picture.

“I knew I couldn’t carry on,” he says. “All this was in my head while playing, and I was just so out of it.”

Bell could barely play, which led him to make a decision that has gone down in rock and roll infamy.

“I sounded like a lot of rubbish,” he admits. “So I threw my guitar in the air, and went over to the amps and kicked all of them off the stage.

"Then I staggered off and just collapsed.”

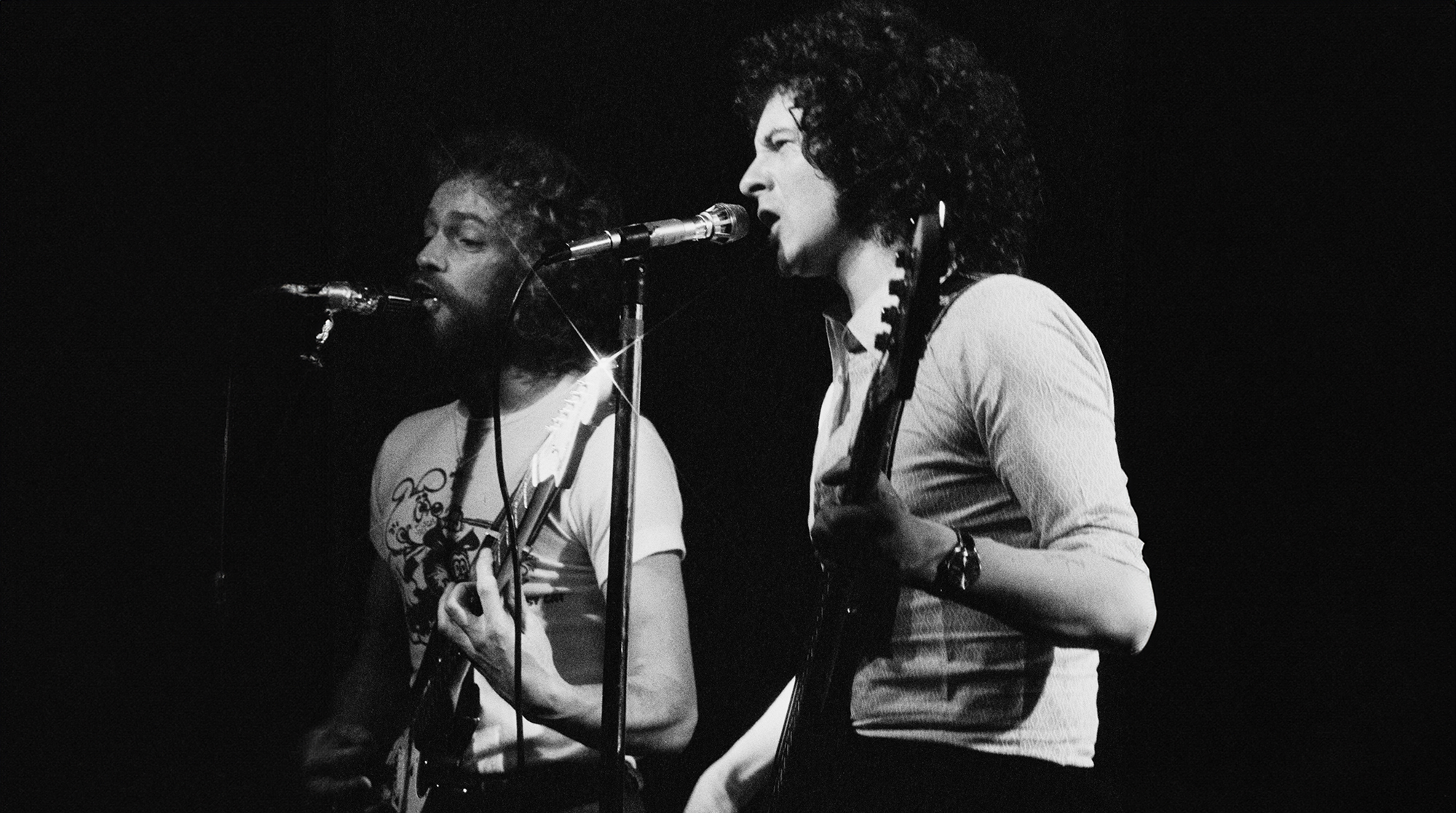

You would think that Bell’s bandmates, Phil Lynott and Brian Downey, would rush to his aid. You might assume that Lizzy’s road crew would call an ambulance for the down-and-out six-stringer. But according to Bell, that’s not what happened.

“One of the roadies came, and said, ‘Get back on that fucking stage!’

“Then they said, ‘Can’t you hear the two guys up there trying their best?’” Bell says. “All I could do was mumble.

"So they got me back on my feet, brought me back onstage, and put my guitar back on me… which was completely out of tune.”

Laughing while shaking his head, Bell continues, “Nobody had tuned the guitar. Some of the springs in the back had even hit the stage. The guitar was completely out of tune.

"I don’t know. I must have sounded like Ravi Shankar on acid. It had to be fucking awful.”

As bad as that gig — and Bell’s hangover — was, what happened next was even worse. “I got a phone call from Lonon, and it was management,” Bell says. “They said, ‘Eric, what the fuck is going on over there?’”

“I told them I’d left the band,” Bell recalls. “They said, ‘What? You’re halfway through an Irish tour. You can’t leave the fucking band.’

“I said, ‘I’ve left, mate. It’s over. I can’t do it anymore.’

“They realized I wasn’t going to do it, and said, ‘Is that your last word?’ I said, “‘Yeah…’

“And they said, ‘Right — we’re getting Gary Moore to finish the tour,’ and slammed the phone down.”

Just like that, Eric Bell’s dream gig was over.

“I just kind of whittled about, wondering what to do with myself,” he says. “But yeah, I’d say that what happened probably saved my life.”

Bell rebounded and landed a gig with the equally hard-drinking Noel Redding later in the 1970s. And though he never rejoined Thin Lizzy, he did reunite with Phil Lynott in the studio for the Jimi Hendrix tribute track “Song for Jimmy,” although he says most of his licks never made it onto the released song.

As for Thin Lizzy, they briefly carried on with Moore before he left. He was replaced with Scott Gorham and Brian Robertson, who forged the twin-guitar harmonies that made Thin Lizzy world famous on songs like “Jailbreak” and “The Boys Are Back in Town.”

As for how he looks back on his final gig with Lizzy, and if he regrets the actions that probably saved his life, Bell sighs.

“I didn’t have the willpower to stop. I could get drunk very easily. If I had two or three whiskeys, I was anybody’s, you know?

“What I could do was keep drinking,” he says. “I’d get drunk easily, but keep going. I was just one of those guys.

“And my Strat that I tossed in the air, I still have it. I think it’s finally just forgiven me.”

He laughs. “But man, it was hard. It took me forever to be able to play guitar straight again.”

Andrew Daly is an iced-coffee-addicted, oddball Telecaster-playing, alfredo pasta-loving journalist from Long Island, NY, who, in addition to being a contributing writer for Guitar World, scribes for Rock Candy, Bass Player, Total Guitar, and Classic Rock History. Andrew has interviewed favorites like Ace Frehley, Johnny Marr, Vito Bratta, Bruce Kulick, Joe Perry, Brad Whitford, Rich Robinson, and Paul Stanley, while his all-time favorite (rhythm player), Keith Richards, continues to elude him.