Stax Legend Steve Cropper on the Genius of Otis Redding and Rod Stewart, and the Thrill of Hearing Your Song on the Radio

The Hall of Famer returns with his “first proper solo album” and reflects on his long and remarkable role in the Stax family and beyond.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

For the past 60-plus years, Steve Cropper has maintained a legendary behind–the–scenes career as a musician, arranger, producer, songwriter, and composer for movies and television shows.

That said, the average casual music fan might only recognize his name from Sam Moore’s calling out just three words on Sam and Dave’s 1967 classic, “Soul Man”: “Play it, Steve!” “Well, it’s like everything else that’s happened in my life,” Cropper says with a laugh. “I accept it with a grain of salt.”

He was born Steven Lee Cropper, October 21, 1941, in the small town of Willow Springs, Missouri. However, the Rock and Roll Hall of Famer has his own pet name for the state.

“I call it ‘misery’ because I grew up on a farm,” he explains. “Most of my friends and relatives don’t like me calling it that, but if you’ve ever chopped corn or spent a whole day filling up a big old gunny sack with beans for a nickel, that was not my idea of fun. Those were the first times I started getting calluses on my hands.“

“Of course, now, after all these years of playing guitar, you could probably shove an ice pick in mine and I wouldn’t even feel it. When I come off the road, though, and it’s too long between shows, my calluses will just peel off until I start playing again.”

Cropper’s initial fascination with guitars goes back to when he was around nine years old in the early ’50s. As he recalls, “The first one I ever plucked belonged to my Uncle Dale Uhlman. I was fascinated by it and would take it out of the closet and pluck it like someone would pluck a rubber band, just to feel the vibrations. Years later, I heard Les Paul and Chet Atkins for the first time, but realized I could never be that good.”

After the first rock-and-roll explosion hit, in the mid ’50s, Cropper became infatuated with guitarists like Bo Diddley and Chuck Berry. He acquired his first guitar by saving money from odd jobs, like setting up pins in a bowling alley, and receiving a little additional help from his parents.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“It was one of those Sears Silvertone country sunbursts with a hole in the middle, like a flattop, and the cost was exactly $17. Or so I thought,” he says, laughing. “I was sitting on the porch for hours, waiting for the delivery truck to turn the corner. When it finally arrived, the guitar was packed in a plain cardboard box – no case – and the driver says to me, ‘That will be a 25 cents delivery charge’ – which I didn’t have.

“I said, ‘What?!’ So I ran into the house and my mom pulled a quarter from her purse. She always liked to tell people, ‘If I’d never have given Steve that quarter, he would have never become a guitar player.’ And she might have been right!”

That $17 dollar investment, of course, paved the way for a very special career that’s still flourishing, 64 years later. It initially took off in 1961, when Cropper’s high school band, the Mar-Keys, made the national record charts with the novelty instrumental hit “Last Night.”

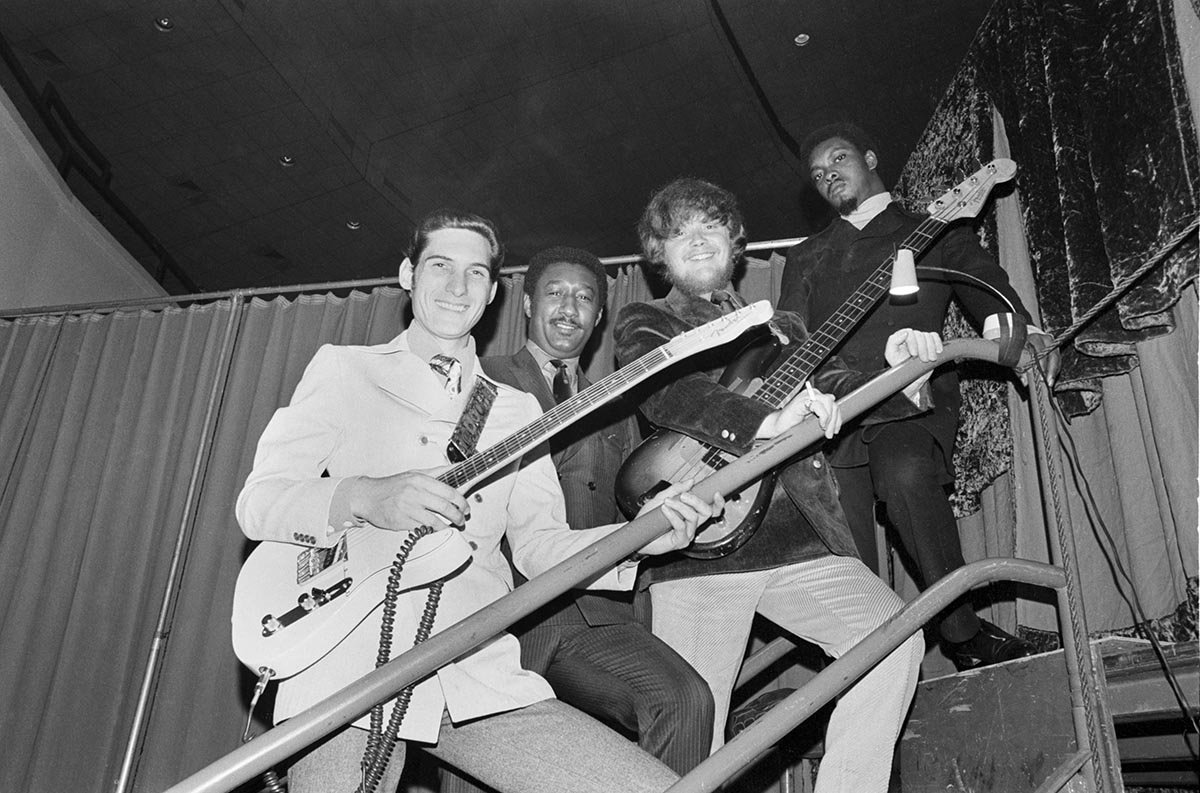

The following year, Cropper teamed up with Hammond organist Booker T. Jones, drummer Al Jackson, and bass player Louis Steinberg (who was replaced by Duck Dunn three years later) in a new group they named Booker T. and the M.G.'s.

As the first prominent interracial rock band, they enjoyed success with such Top 40 hits as “Green Onions,” “Hip Hug-Her,” and “Time Is Tight.” But they were also the house band for the Stax record label and performed on hundreds of sessions for such prominent artists as Otis Redding, Albert King, and Wilson Pickett, before disbanding in 1971.

At 79, Cropper is as busy as ever, adding his famed guitar licks to the latest albums by Paul Simon, Ringo Starr, and Buddy Guy.

He’s also coming out with a new CD, Fire It Up (Mascot Label Group), which features guest stars that include former Rascals leader Felix Cavaliere, singer Roger C. Reale, and drummers Simon Kirke (Bad Company), Chester Thompson (Genesis), and Anton Fig (Paul Shaffer and the World’s Most Dangerous Band). Cropper calls it “my first proper solo album in more than 50 years.”

How did the Covid-19 pandemic impact the methods you used to record this new album?

This is actually the fourth album I’ve co-produced with Jon Tiven. Normally, we would work together in person, but because of the pandemic, all of us had to work separately. On our earlier albums, Jon would be present for the mixes. This time, he stayed at home but still had everything worked out in advance.

I just overdubbed my parts on my own, doing the basic rhythm tracks and then overdubbing some solos and some licks. We did have a lot of guest artists on the last album we did together, but this time I wanted to keep that to a minimum.

There were different drummers, though, on some of the tracks. We would record to a loop and then replace it with a real drummer. I never did get to meet Mickey Curry or Simon Kirke, but overall, everything on the album worked out fine.

It didn’t matter if Rod missed a lyric. Whenever he came into the studio to record, he always made sure to give his best performance to get the same from the musicians

Technology has obviously changed greatly since you first started recording at Stax. What are some of the pros and cons between the way you used to record and the way albums are made now, where everyone just basically records their own parts separately? Do you miss the live give-and-take interaction of playing with other musicians?

I’ve been away from technology for a long time, and I’ve really let it pass me by, so I’ve had to surround myself with people who are really good with it. I do a lot of overdubs. People want me to play on their records, so they send me .WAV files, which go right into Pro Tools, and it usually works out pretty good.

My engineer will look for the best take to use. The only problem is you have to remember what you did a few days ago. When we used to have only four tracks, you didn’t have to remember that much.

How did Roger C. Reale get to do all the singing on the album?

Because of the pandemic, Roger didn’t want to come to the studio to do any of his parts there. So I’ve never met him either, but the first time Jon sent me a recording of his voice, I said, “Where was this guy when I needed him 40 years ago? How come I don’t know about him? Does he always sing with this kind of passion?”

There are only two other singers that I’ve worked with in my production lifetime who were like that. One was Otis Redding, who sang every song like it was the last song he was ever going to sing. The other guy’s name was Rod Stewart, who did the same. It didn’t matter if Rod missed a lyric. Whenever he came into the studio to record, he always made sure to give his best performance to get the same from the musicians.

I used to play a Telecaster straight up, using both pickups. It just seemed to work better because it took all of the brittleness out if I played it wide open

What was your main guitar on the album?

It’s made by Peavey, but it’s basically a Telecaster copy, except the headstock is different than a Fender. For seven years we had the [Peavey] Cropper Classic, but this one is different. It’s more like the Wolfgang, but it’s not a dead ringer. It has three tuning pegs on the top and three on the bottom, where Fender’s has six in a row. That’s one of the basic differences.

The other is that I used to play a Telecaster straight up, using both pickups. It just seemed to work better because it took all of the brittleness out if I played it wide open. Onstage, I will do the little finger-volume thing to adjust my level, but on the sessions I just let the engineers decide what it should be.

On the album, do you use any special effects with your guitar?

No, but when I was with Booker T. years ago, I used tremolo a lot. I’m a one-sound-at-a-time guy. Very limited. All I’ll do now is use a little tremolo once in awhile.

All of B.B. King’s effects were in his left hand, and that worked out well.

There are tons of guitar players out there that imitate what B.B. King did, what is known as “The Shake.” I could never move like that.

What do you find so special about the Telecaster that you’ve made it your signature guitar?

Well, first of all, if you hit a chord on a Gibson, it’s going to distort, and the engineers have to do a lot of mixing to clean it up. If you do the same thing on a Telecaster, it won’t do that. If I was a solo artist, though, I’d probably play a Les Paul, because the notes just sustain better. But with the right gear, you can make a Strat do the same thing.

The Strat also bites a little more than a Les Paul does. I actually started out with a Gibson, as have a lot of people who play blues or jazz.

It’s a warmer sound and you can bend the strings easier, but overall in the studio a lot of producers and engineers prefer a Tele, because if you play a backbeat – what we used to call “chinks” – it would strengthen the snare drum. If you hit it dead on, it would really make it sound big.

Did you have a preferred amp for this album?

Yes, it was the Victoria 80212, modeled after the Fender Twin. It has a tweed covering, and it’s all handmade, even the vacuum tubes. Since ’91 though, onstage I’ve been using the Fender Twin “Red Knob,” but the sound is too bright and brittle for recording. When I was at Stax, my regular amps were either a Fender Harvard or a Super Reverb.

Let’s talk a little about your musical history. Living in Memphis at age 15 in 1956, when Elvis became an overnight sensation, was he a role model in any way?

Like a lot of kids my age, I tried combing my hair and dressing like him. Elvis originally lived about two blocks from me before moving to Graceland. In the 12th grade, I got to go there a few times and hang around, because some of his bodyguards were dating some of our seniors.

I remember this one time Elvis was standing on the top of the staircase, staring right down at me and probably thinking, What are this snot-nosed kid and his friends doing in my living room? I’m going to go to jail for this! [laughs] So, of course, we stayed pretty quiet and out of his way.

As far as Elvis being a musical influence, I was more into people like Hank Ballard and the Midnighters, and the “5” Royales, whose guitar player, Lowman Pauling, was one of my heroes. I did a whole tribute album to him a few years ago. But Elvis did sing and play R&B-rooted ethnic music, and he really did a pretty good job of it.

I remember this one time Elvis was standing on the top of the staircase, staring right down at me and probably thinking, What are this snot-nosed kid and his friends doing in my living room? I’m going to go to jail for this!

Was hearing James Burton’s Telecaster-infused solos on those great early Ricky Nelson records like “Believe What You Say” and “Waitin’ in School” an influence on you?

I didn’t know it was James back then, because session guys weren’t credited. But yeah, those were great records. I didn’t get to meet James until ’65, when Booker T. and the MGs were on the Shindig television show and he was part of the house band, the Shindogs. He and I have total respect for each other.

You were instrumental in convincing Bobby Whitlock to go visit Eric Clapton in England back in ’69, which of course led to the formation of Derek and the Dominos.

The reason I sent Bobby a plane ticket to Eric’s was because I couldn’t do anything with him at Stax. He said, “How come?” I said, “Because you’re a blue-eyed soul singer!” [laughs] I had the same problem with an album I produced for Mitch Ryder. The ethnic DJs at the time wouldn’t play a White artist, which I fully understood, so I was caught in the middle.

In 1966, the Beatles were considering coming to Memphis to record with you at Stax, but that never materialized.

Yes, they were definitely interested, but what happened was Brian [Epstein, the Beatles’ manager] came without them to Memphis to check things out, and he felt security wouldn’t be good enough, so I never did get to work with the Beatles.

After I heard the album, which was Revolver, I said, “I’m sure glad I didn’t have anything to do with producing it, because I’d have changed it, and probably for the worse.” [laughs] Later on, I did get to work with Ringo a couple of times and John Lennon on his Rock ’n’ Roll album in the ’70s.

You’ve also enjoyed a lot of success as a songwriter. Songs like “Knock on Wood,” “(In the) Midnight Hour,” and “(Sittin’ on) The Dock of the Bay” are still being played all these years later. How did “Knock on Wood” with Eddie Floyd come about?

Back in ’66, I met Eddie at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis [the site of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination two years later]. I opened the door of his room, and right away Eddie says, “I have a great idea for a song. It’s about superstitions.”

So we started coming up with every one we could think of: black cats, walking under ladders, opening umbrellas indoors, throwing a glass over your shoulder... Then I finally said to Eddie, “What do people do for good luck?” and right away he starts knocking on the edge of his chair. I said, “That’s it. There’s our song!”

“(Sittin’ on) The Dock of the Bay” must have a lot of bittersweet memories for you, because Otis Redding died before knowing what a big hit it would become.

Yes, that’s true. One day, Otis called me on the phone and said, “I’ve got a sure hit, but I need you to help me finish it.” So after he met me at the studio and played me the first part, I wound up helping him finish one of the verses and also wrote the bridge and the changes, but we both felt it was still too raw.

I said, “If we put strings on it, that will kill it,” and he agreed. I was getting ready to produce the Staples Singers, and Otis thought having them on the record was a great idea. Before he left that day, he poked his head in the control room and said, “I’ll see you on Monday,” but, sadly, he died just a few days later.

Before the record was released, I added a few guitar licks but still felt something was missing. That’s when I came up with the idea of adding the sounds of crashing waves and seagulls.

What memories do you have of working with John Belushi and Dan Aykroyd as part of the Blues Brothers?

When some of my musician friends first heard that I was planning to work with them, they said, “What are you and Duck doing playing with those stupid comedians?” That all changed as soon as anyone saw us perform together. Belushi was a terrific singer, and Aykroyd played a mean blues harmonica.

Of course it’s well known that John had a major problem with drugs and alcohol. For the year and half that Duck and I toured with him, we tried our best to keep him sober and away from the drugs, but he wouldn’t stop until the drugs ultimately killed him.

Belushi was a terrific singer, and Aykroyd played a mean blues harmonica

In your long career, what has been most memorable or rewarding?

It’s really hard to say, but for me some of my fondest memories are from when I’ve collaborated with someone on a song, and then hearing it being played on the radio for the first time. That was always as exciting as the first time my dad took me to the park.

With your 80th birthday coming up later this year, do you still have any unfulfilled ambitions?

A reporter once asked me, “Steve, what’s on your bucket list?” I said, “Just trying not to kick it!” I know I’m getting old and everyone dies, but I want to keep a young attitude as long as I can.

So what epitaph would you want written on your gravestone?

I think “Play it, Steve,” would be good. I’ll have to tell my wife to make sure not to forget that. [laughs]

- Fire It Up is out now via Mascot Label Group.