“My own son didn’t know who I was until he could turn 21 and get into the blues clubs. He said, ‘Dad, I didn’t know you could play like that!’” Now 89, guitar legend Buddy Guy explains why he “ain’t done with the blues” yet

Two years after retiring from the road, Guy is still out there. His new album drops July 30

It was just two years ago that Buddy Guy announced a Damn Right Farewell Tour and talked about winding down his touring career.

But you might have noticed that, at 89, the dude is still on the road. And he’s coming out with a new album whose title is a straight-up statement of his attitude — Ain’t Done With the Blues.

“Yeah, I thought about retiring twice,” the Louisiana-born Guy tells us, with a chuckle, by phone from his home in Chicago, where he operates his Buddy Guy’s Legends club. “But, y’know, I thought about all those great blues players who are no longer with us — B.B. King. Lightnin’ Hopkins, all those guys — and they used to tell me, ‘You need to keep playing and keep representing the blues,’ ’cause they don’t play it on radio or anything anymore.

“So I said to myself, ‘Well, Buddy, you better hang on a little longer. My health ain’t doing too bad, so I’m still doing what I’ve always done...every time I get on stage, just try to play the best I can.”

Guy has certainly been rewarded for that over the past 60-plus years. He has nine Grammy Awards — including a Lifetime Achievement nod — a Kennedy Center Honor, a National Medal of Arts, a Golden Plate Award from the American Academy of Achievement and inductions into the Rock and Roll, Musicians and Louisiana Music halls of fame.

There’s a marker honoring Guy on the Mississippi Blues Trail, and this year his profile was bumped again by an appearance in the hit Ryan Coogler film drama Sinners, playing the elder version of one of the story’s main characters and performing the song “Travelin.’”

“He’s inspirational,” says Christone “Kingfish” Ingram, who counts Guy as a valued mentor.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“When you hear him play, you just know that’s the way it’s supposed to be done.”

Tom Hambridge, the Nashville-based producer who’s helmed Guy’s last seven albums — from 2008’s Skin Deep through Ain’t Done With the Blues — is not at all surprised that farewell did not really mean goodbye.

“This is what he knows,” Hambridge explains. “He seems very content living on a stage — ‘Put a guitar in my hand and lead me to the stage and I want to play with people.’ That’s what he’s been doing his whole life.

“And I think he really means it when he always says he wants to keep the blues alive and keep the word he gave to Muddy [Waters] and all of them. He thinks if he’s out there doing it, making new music, he’ll be keeping the blues alive.”

The blues has been treated like a stepchild. When I was coming up you could turn your radio on and you could hear everything.”

— Buddy Guy

You can still hear exasperation and anger when Guy — the son of sharecroppers who learned to play on a two-string diddley bow — addresses that mission, as he has for a great many years now.

“The blues has been treated like a stepchild,” he says. “Your big FM station don’t play our music anymore. When I was coming up you could turn your radio on and you could hear everything. You didn’t just hear B.B. King or Lightnin’ Hopkins all day. They played everybody — horn players, keyboard players, guitar players, gospel, jazz, blues. We don’t have that no more. If you’ve got satellite radio, you can hear a little more, but they don’t play the deep stuff.

“My own son didn’t know who I was until he could turn 21 and get into the blues clubs. He said, ‘Dad, I didn’t know you could play like that!’ And whenever we play these little outside theaters, you get these kids — seven, eight, nine, 11 years old — they come and come up, like, ‘Wow, man, I didn’t know who you was!’

“And not me — the blues. When they hear it, they love it. They just ain’t hearing it enough, so...that’s why I’m still here.”

He’s hopeful that Sinners’ success will help build that audience, too, even though Guy says that “I didn’t pay too much attention to it” after he filmed his parts. “They say it’s doing pretty well, which is good,” he notes. “I’ll do anything to help the blues, and that family [in the film] is kinda based on the blues. I think Sinners might help it a little bit, ’cause maybe some young kids will be like, ‘Wow, I saw that movie. I like what he played. I wanna try that.’”

Hambridge says that, like the other projects, Guy made the call for Ain’t Done With the Blues. Then he went to work writing and accumulating songs.

When they hear it, they love it. They just ain’t hearing it enough, so...that’s why I’m still here.”

— Buddy Guy

“Every time he asks me to do another one, I try to reinvent it, somehow, and think, ‘How can we do it so it’s not like what we did before?’ and I’ll throw ideas at him,” the producer explains. But, he adds, “Buddy is a creature of habit. I’ll even say, ‘Let’s go somewhere else. Let’s go to London to record. How about we do this?’ And it’s, ‘No, just do it the way you do it, because it works.’

“That’s probably why he’s so successful — ‘If something’s not broke, just do it that way.’”

For Guy, meanwhile, it’s simply a matter of “when I go in the studio, I just try to give you my best. I even wrote a song from what my dad told me one time — ‘Buddy, don’t be the best in town/just be the best ’til the best come around.’ And he meant pickin’ cotton, driving tractors or a truck, whatever. He didn’t say, ‘That’s just music I’m telling you about.’ He meant, ‘Whatever you do, do the best that you can.’”

Their process remained the same as always on Ain’t Done With the Blues. Hambridge sent batches of songs ideas to Guy, who’d weigh in on what he liked best and which Hambridge would then continue to develop.

“Sometimes we go in with 20, 25 things we’re possibly going to record,” Hambridge says. “And there’s time he comes in and says, ‘Hey, I got an idea about a line that came to me when I was sleeping’ and I’ll sit down with him in the studio and we’ll write that song and he’ll go, ‘Yeah, let’s record that.’”

Guy’s take? “They give me the song and I don’t want to listen to it, ’cause I might overdo it or underdo it. I just say, ‘Lemme hear it’ and hopefully I can play a note or something or say a lyric somebody will pay attention to.”

Covers, according to Hambridge, tend to be a hard sell to Guy.

“He really wants to be original,” explains the producer, who also wrote tracks with Nashville cats such as Gary Nicholson and Richard Fleming. “He really wants to say something. If it doesn’t touch him, he doesn’t want to sing that song. I really respect that in him.”

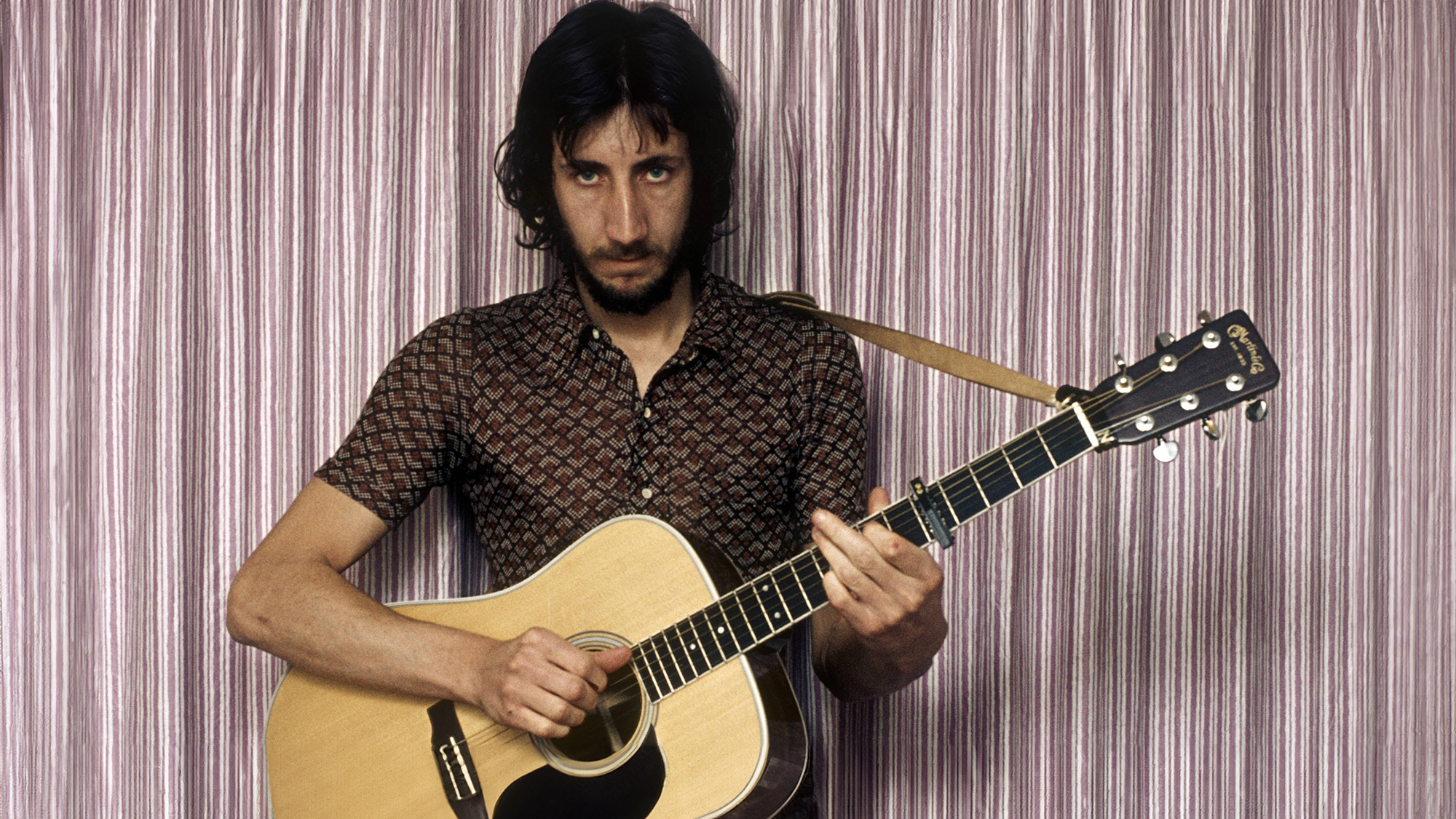

That said, Ain’t Done With the Blues starts with “Hooker Thing,” a John Lee Hooker vamp, and also includes “One From Lightnin’,” which apes Hopkins, both featuring Guy alone with just his signature Martin acoustic guitar. And it was Guy’s idea to record Earl King’s “Trick Bag,” while Hambridge has been lobbying for J.B. Lenoir’s “Talk To Your Daughter” “for a long time.

Recording Guy with his Martin is a particular joy for Hambridge. “When he plays that, he plays different,” the producer says. “It sometimes sounds electric; we put different things in, run ’em through an amp. A lot of people will think that’s an electric guitar, but I like it because he does play differently.

:I kinda try to trick him a little bit, because he’ll say he just wants to play electric and fast, and I’ll say, ‘Can you just go out and test the mic, maybe sing something? Sing me a John Lee Hooker song? And he goes, ‘Here’s a Hooker thing’ and he’ll start and it’s unbelievable. I’m standing there next to him and tell the engineer to just roll it. he’ll say, ‘Is that okay?’ and I’ll say, ‘Sure, but can you give me a little more...’ and we’re recording the whole time and getting great stuff.”

Both Guy and Hambridge agree that the former’s playing has gone through a bit of an evolution during their time together.

“When I started working with him, he was playing fast and doing all this [sings a run] really crazy stuff,” Hambridge says. “I remember him saying to me, ‘They like when I do that — the audience, the crowd.’ And I said, ‘Well, you know better than me...but we’re making a record here. I miss some of the more spacious, clean, B.B. King kind of notes.’

“So we’d try that on stuff, and it’d be beautiful. I try to get some of that on these albums and still let him have the faster stuff on there as well.”

Some guitar players say to me, ‘What do I need to do, Buddy?’ and I say, ‘Just keep playing, ’cause you never know what will happen.’ That’s what I do.”

— Buddy Guy

Guy — who recorded most of the album on a 1988 blonde Fender Stratocaster and more recent versions of his signature polka-dot Strat — recalls that, “B.B. King and even Aretha Franklin told me, ‘You can’t holler that loud your whole life — meaning the way I play, too. I used to laugh at them when they’d tell me that...I just play what I know. Every time I pick up my guitar I just hope I hit something nice and play the right note at the right time.

“Some guitar players say to me, ‘What do I need to do, Buddy?’ and I say, ‘Just keep playing, ’cause you never know what will happen.’ That’s what I do.”

Ain’t Done With the Blues also features a variety of guests: Kingfish on “Where U At?;” Joe Walsh on “How Blues is That?,” Joe Bonamassa on “Dry Stick,” Peter Frampton on “It Keeps Me Young,” and the Blind Boys of Alabama on the gospel-flavored “Jesus Loves the Sinner,” along with top-shelf players such as Rob McNelley on guitar, Glenn Worf and Tal Wilkenfeld on bass, Chuck Leavell on piano and others.

“All these guys, they’re such superstars themselves, but they just love Buddy,” Hambridge says. “Everybody I’ve reached out to through the years, especially on this record, nobody says no. They all go, ‘Are you kidding me? I’ll drop everything to do this!’ That’s Billy Gibbons, Keith Richards, Jeff Beck, Mick Jagger...whoever. They all want to be part of it.”

Will there be more coming to be part of? That’s a question only Guy can answer — and he doesn’t necessarily have it yet.

“I don’t know if I know how to say ‘no,’” he says with a chuckle. “I really didn’t say I was through. I know a lot of groups that have thrown their farewell tour and they’re still out there, so I don’t know if that made a couple more people come to see them or not. I didn’t want to do that.

“The Muddys and all of them told me, ‘Know when it’s time for you to get out of the way and let these young people take over.’ I want that to happen to me. But whatever I can do to help the blues stay alive, I’m still gonna try to do that.”

Gary Graff is an award-winning Detroit-based music journalist and author who writes for a variety of print, online and broadcast outlets. He has written and collaborated on books about Alice Cooper, Neil Young, Bob Seger, Bruce Springsteen and Rock 'n' Roll Myths. He's also the founding editor of the award-winning MusicHound Essential Album Guide series and of the new 501 Essential Albums series. Graff is also a co-founder and co-producer of the annual Detroit Music Awards.