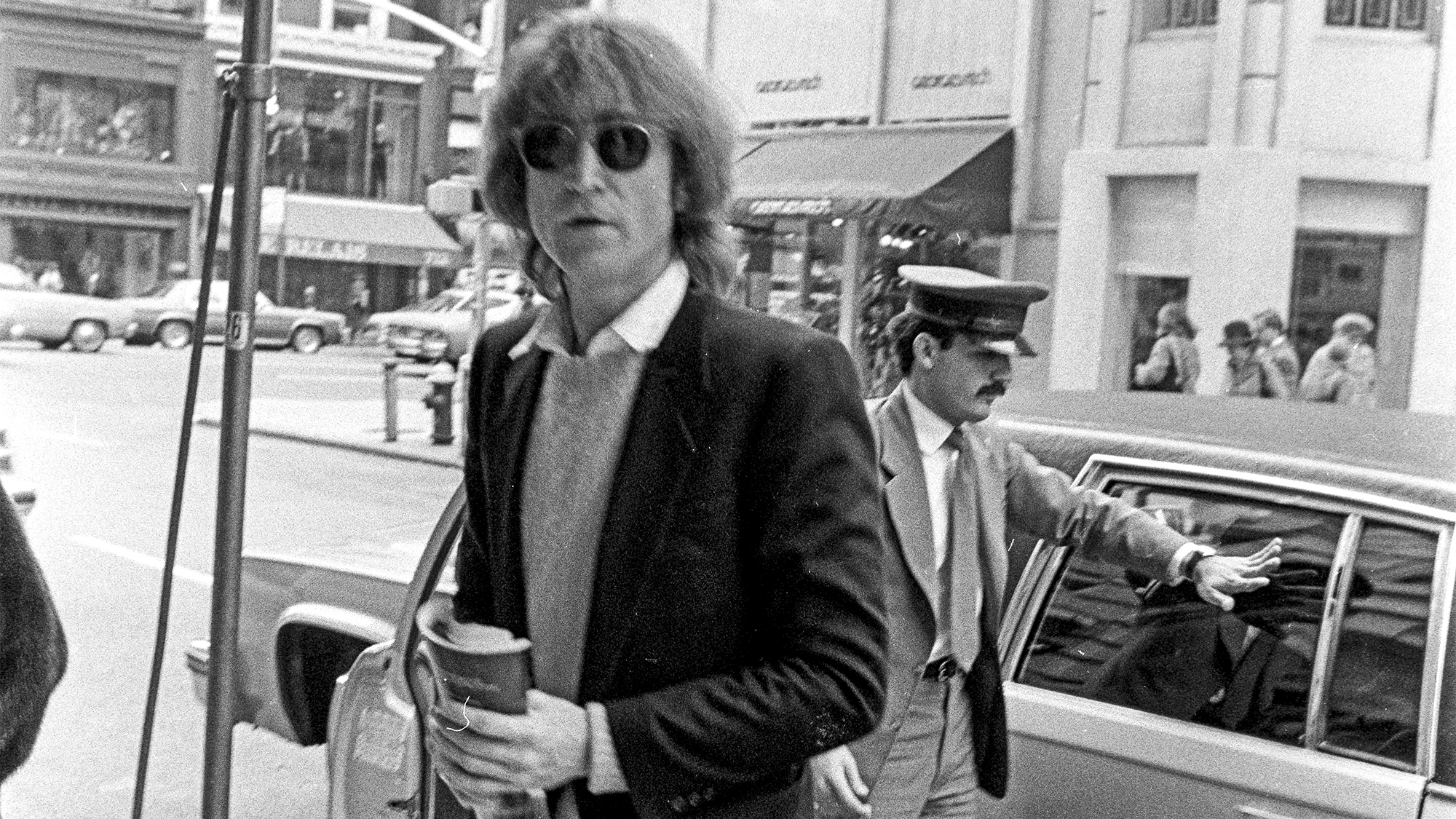

“One of the nurses said, ‘John Lennon.’ I thought, What does John Lennon have to do with it?” A surgeon remembers the night he tried to save the former Beatle’s life

Frank Veteran was on call the night Lennon was shot. He was the last doctor to attend to the slain Beatle

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In 1980, Frank Veteran was a resident in surgery at Roosevelt Hospital on New York City’s west side. At 30 years old, he was in his fifth and final year of surgical training Between the pressures of medical school and his job, he’d had little time to keep up with current events, let alone the comings and goings of his childhood heroes.

“I was into the Beatles, and I followed them,” Veteran told me when we spoke in 2005 for a Guitar World Presents special issue. “But by the time I was the chief resident in surgery, I wasn’t listening to them anymore. I was too busy. I didn’t even realize John Lennon was living in New York.”

One of three chief residents at Roosevelt, Veteran was on call for emergencies every third night. There, he attended to the routine injuries of city life.

“Gunshot wounds, stab wounds. You wouldn’t have to be in the hospital all the time, but if anything happened, you’d have to come in and take one of the younger residents through the procedure,” he explained. “When you were chief resident, you were the primary head doctor. You ran the whole show.”

On the night of December 8, 1980, the show was unlike any Veteran had seen before.

He’d spent the evening at his girlfriend’s apartment, on 10th Avenue, across from the hospital. Around 11 o’clock, as they were getting ready for bed, his beeper went off.

“They said, ‘We have a gunshot wound to the chest,’” Veteran recalled. “I asked, ’What’s status of the patient?” They said, ’Well, Dr. Halloran’ — one of the younger residents — ‘is opening his chest.’ I said, ‘Well, if Halloran is opening his chest, you don’t need me.’”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Opening the patient’s chest, Veteran explained, is a last resort, performed when the heart has stopped and the patient is unlikely to live. “But they said to me, ‘No, we need you now!’”

Puzzled by the call, Veteran dressed quickly, took the elevator down to the lobby and ran across 10th Avenue to the hospital. As he walked upstairs and down the hall to the emergency room, he encountered a pair of nurses.

“One of them looked at me and said, ‘John Lennon.’ I looked at them and thought, What does John Lennon have to do with it? It made no sense to me. It was so ridiculous that it didn’t even register.”

As Veteran entered the ER, the significance of the nurse’s remark became vividly clear.

“I walked in, and there was John Lennon, on the table, with all these people around him.”

Just minutes earlier, Lennon had been shot while returning with his wife, Yoko Ono, to their home at the Dakota, a luxury apartment building on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. Bleeding heavily, his vital signs quickly ebbing, Lennon had been sped to the hospital by officers who had responded to the shooting.

“Standing there, suddenly, everything just hit me,” Veteran said. “For some reason, I thought of John Kennedy and Jesus Christ. It was just a weird thing that flashed in my head.”

The doctors had already begun trying to resuscitate Lennon. “His chest was open,” Veteran said. “They were doing everything to save him.”

He stepped up to the surgery table and took a grim assessment of the patient. Lennon had been shot four times from the left at point-blank range with a .357 magnum revolver. Two bullets had passed through his left upper arm and entered his chest; two more entered his chest just behind the arm.

Traveling through his torso, they ripped through his lungs and arteries. Three of the bullets exited the front of his chest: one under his left clavicle and two on the left side of his sternum. The fourth remained lodged inside his body.

According to Veteran, the worst injury was to Lennon’s subclavian artery, a major branch of the aorta, the heart’s main artery.

“He was bleeding heavily.”

For 20 minutes, Veteran and his associates worked to get Lennon’s heart beating again.

“Once your heart stops, you have five minutes, basically, to resuscitate it before lack of oxygen causes brain injury,” Veteran explained. “So how long does it take to get from the Dakota to Roosevelt Hospital, get into the emergency room, get stripped, get your chest opened? Well, it takes longer than five minutes.”

Lennon’s heart never beat again.

“And had we gotten it going, he would have been brain dead. It would have been a disaster anyway.”

Veteran recalled a conversation he had with an officer on the scene at the Dakotas. “He said the last evidence of any life was a groan when they put him in the backseat of the police cruiser.”

At 11:15 p.m., Lennon was pronounced dead. Chief medical examiner Dr. Elliott M. Gross said after the autopsy that Lennon died of shock and blood loss and that no one could have survived more than a few minutes with such injuries.

Veteran was still in surgery attending to Lennon’s body when he heard a scream from a nearby room.

“That was Yoko Ono,” he says. “The head of the emergency room had given her the news. It was a horrendous scream.”

For months afterward, Veteran suffered from depression.

“I’d feel normal, and then I’d wake up in the middle of the night in this deep depression. It took six months for that to go away.”

During his tenure at Roosevelt, Veteran estimates that he attended to as many as four gunshot or stab wounds each night. “I was used to it. I didn’t feel freaked out. But something deep down affected me that night.”

By the next year, he was a practicing plastic surgeon. When we spoke in 2005, Veteran had left the medical profession and become an investor on Wall Street investor. Simultaneously, for the preceding two decades, he had pursued his craft as a painter of abstracts. He had recently been the subject of a sculpture by New York artist Keith Edmier, who built a series of pieces around the former surgeon’s memories of December 8. The centerpiece was a cassette boom box that played a tape on which Veteran related the story of what happened that night. Physically and psychically, the events of December 8, 1980, never left him.

“I was a kid when Kennedy was assassinated,” he said, “and I remember watching [Lee Harvey] Oswald” — Kennedy’s alleged assassin — “get killed on live TV.” He recalled how, just three months later, he was watching again when another transformational moment in American history took place: the Beatles’ February 9, 1964 appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show.

“I was a big Beatles fan,” he said, sounding suddenly younger as a glimmer of light entered his voice. “How couldn’t you be?”

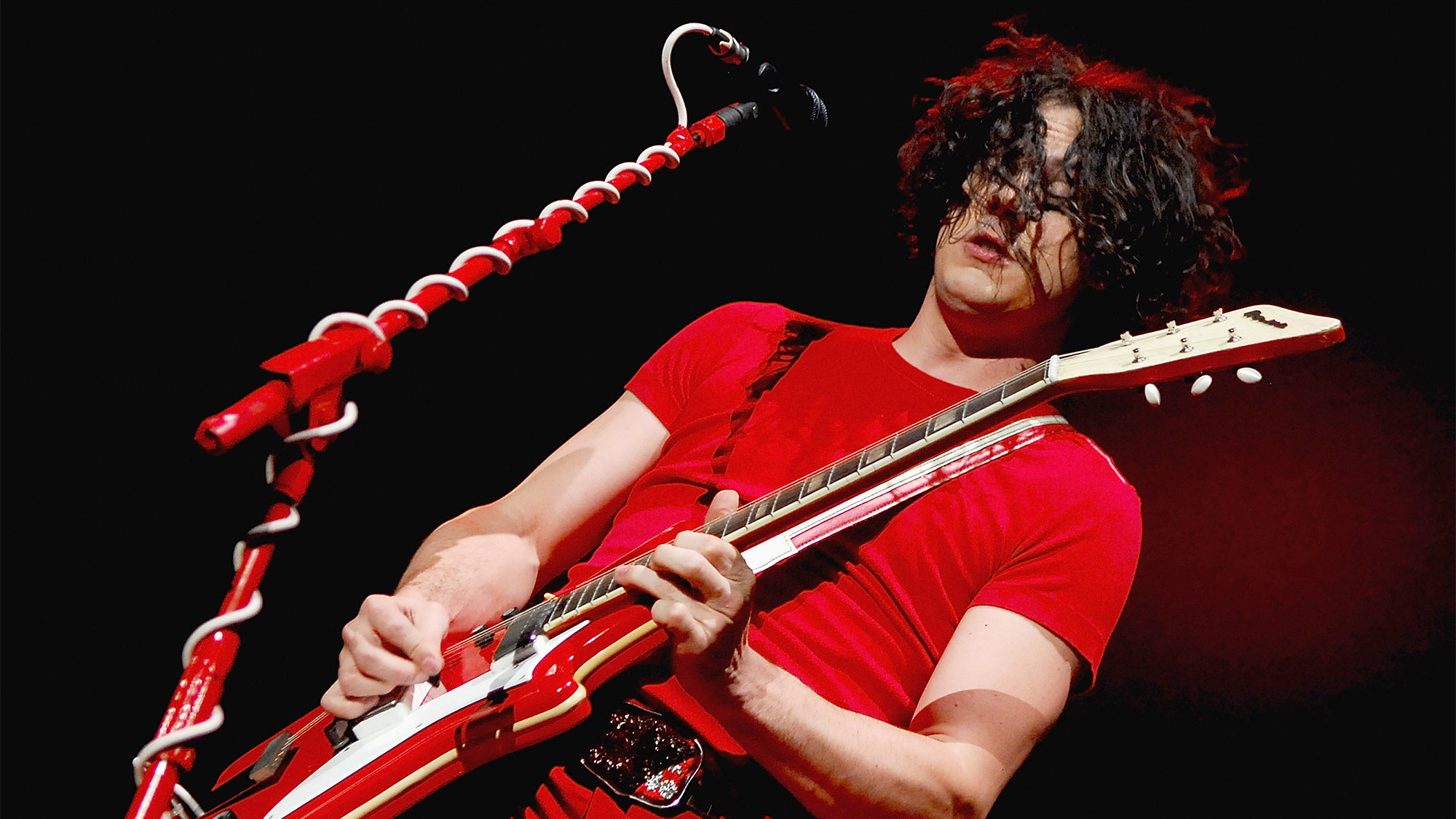

Christopher Scapelliti is editor-in-chief of GuitarPlayer.com and the former editor of Guitar Player, the world’s longest-running guitar magazine, founded in 1967. In his extensive career, he has authored in-depth interviews with such guitarists as Pete Townshend, Slash, Billy Corgan, Jack White, Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren, and audio professionals including Beatles engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott. He is the co-author of Guitar Aficionado: The Collections: The Most Famous, Rare, and Valuable Guitars in the World, a founding editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine, and a former editor with Guitar World, Guitar for the Practicing Musician and Maximum Guitar. Apart from guitars, he maintains a collection of more than 30 vintage analog synthesizers.