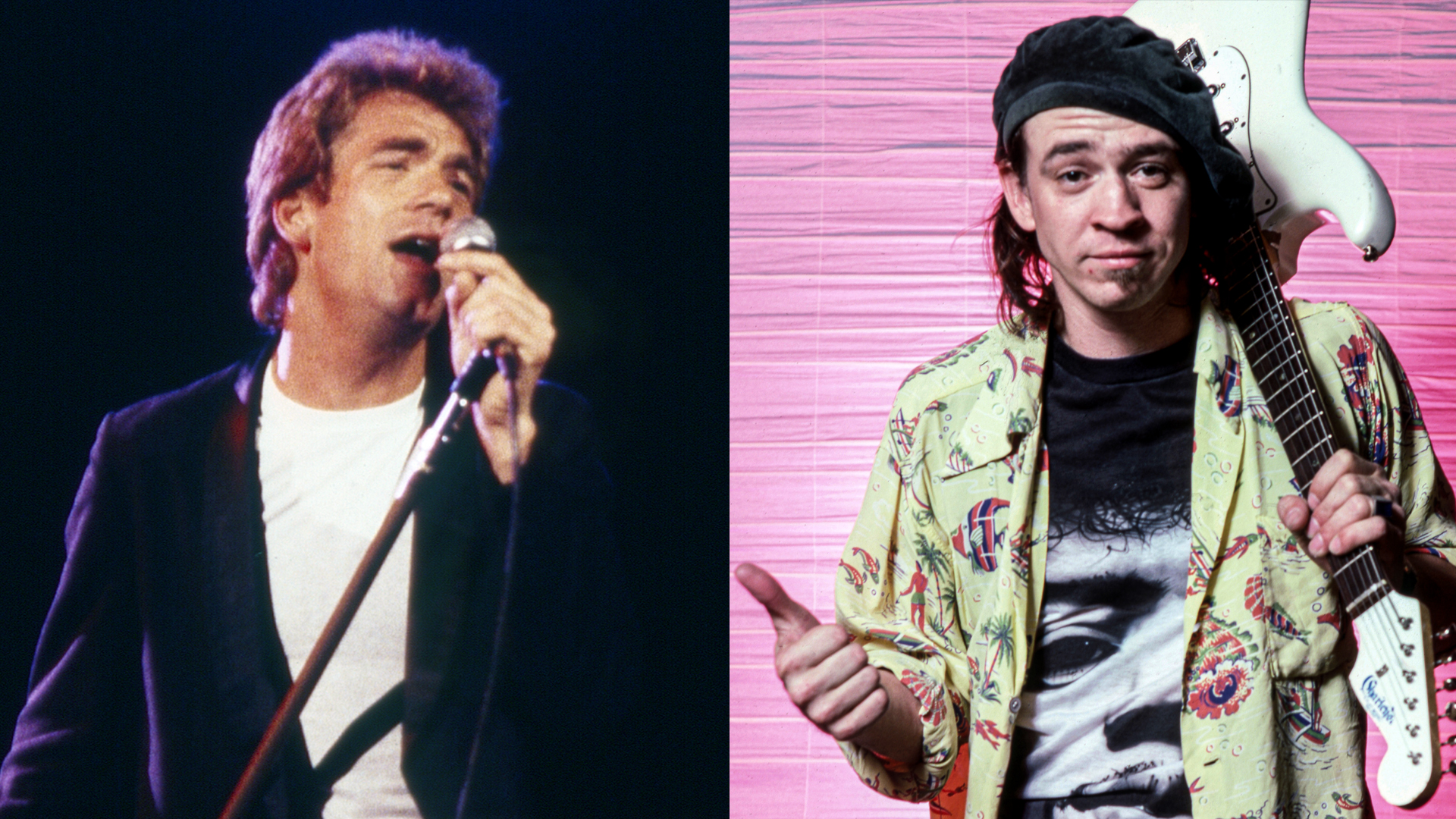

“Wiped the whole hand out. The end of this thumb was off. The fingers were just danglin’, hangin’ off.” The King of Rockabilly on the gruesome onstage accident that nearly ended his career — and his life

Carl Perkins was friends with Elvis and inspired the Beatles. But in a split second, one of rock and roll’s pioneers was nearly silenced forever

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

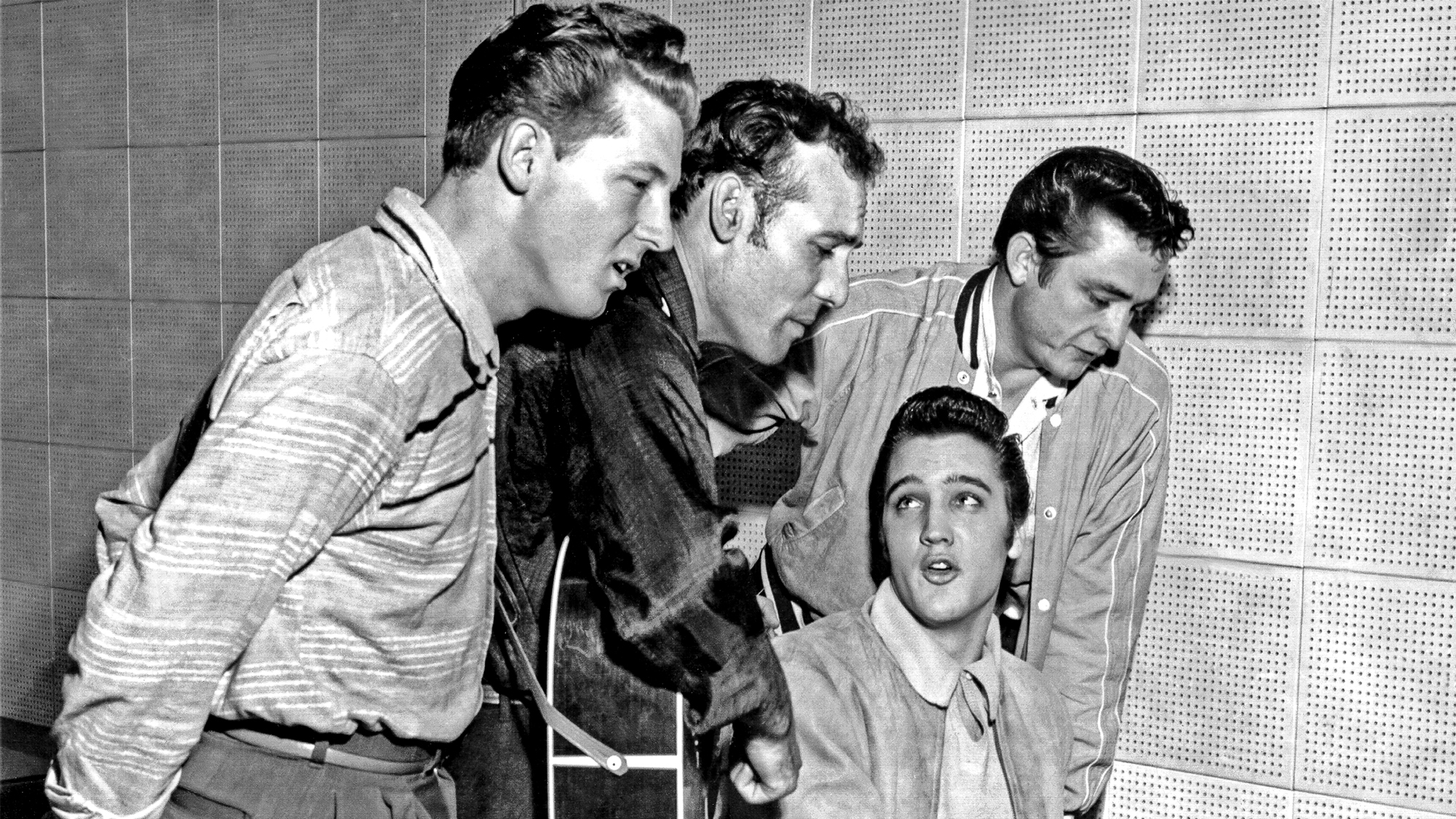

Carl Perkins was a rockabilly pioneer who sang with Elvis Presley, hung out and toured with Johnny Cash and wrote classic rock and roll tunes like “Blue Suede Shoes,” the first recording to top the pop, country and R&B charts simultaneously.

The country-inflected guitar licks he coaxed from his 1953 Les Paul Goldtop inspired George Harrison’s early electric leads and solos with the Beatles. The group’s admiration ran deep: They covered at least seven Perkins songs onstage and in the studio, including “Everybody’s Trying to Be My Baby,” “Matchbox” and “Honey Don’t.” As Paul McCartney declared, “If there were no Carl Perkins, there would be no Beatles.”

But in less time than it takes a metal fan blade to spin, Perkins nearly lost his career. And his life.

Article continues below

It happened one night in 1962 at the end of a live set in Tennessee as he stepped forward to take a bow.

“We were playing on a trailer in a courthouse yard. Somebody put a big window fan on the side. It had no frame on it. I was taking the guitar off, taking a bow, when I stuck my hand in there,” he told Musician magazine’s Bill Flanagan.

Somebody put a big window fan on the side. It had no frame on it.”

— Carl Perkins

“Wiped the whole hand out. The end of this thumb was off. The fingers were just danglin’, hangin’ off.”

The nearest hospital was 60 miles away. Perkins wrapped his mangled right hand in a towel and climbed into the back of a ’62 Buick for the impossibly long ride. The fan blade had severed the main arteries of his picking hand, and blood pulsed out with every heartbeat.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

He recalled how “blood filled the floorboards and was running out the back doors.”

As his life literally drained away, Perkins felt himself crossing over. The car seat fell away beneath him and he saw a gray tunnel, beyond which shone a sky the colors of blue and orchid.

“I went through that passing from life,” he said. “I was just floatin’ like a feather through those beautiful colors.”

I went through that passing from life. I was just floatin’ like a feather through those beautiful colors.”

— Carl Perkins

He held on long enough to reach the hospital. The surgeon on duty recommended amputating the damaged fingers, saying they would only get in Perkins’ way — if he survived. His wife begged the doctor to save them, and he reluctantly agreed to try.

Perkins woke the next afternoon in a hospital bed, his hand in a cast and his wife and the surgeon at his side. Against the odds, his hand had been saved.

“I was happy to have a thumb left — anything!” he said. “I tuned my guitar in open E, laid it across my lap and picked with the end of my thumb with that big cast on. I was gonna play!”

Over time, Perkins regained the use of his thumb and first two fingers. He never recovered full use of his pinkie, which had been essential to his intricate Chet Atkins–inspired picking style. It didn’t matter. He was grateful simply to play again.

“People have told me, ‘Carl, you play better than you ever did.’”

Rockabilly’s simple music, but it’s not that easy to play, If you ain’t tappin’ your foot, you’re missin’ the boat. Might as well go on to the next club.”

— Carl Perkins

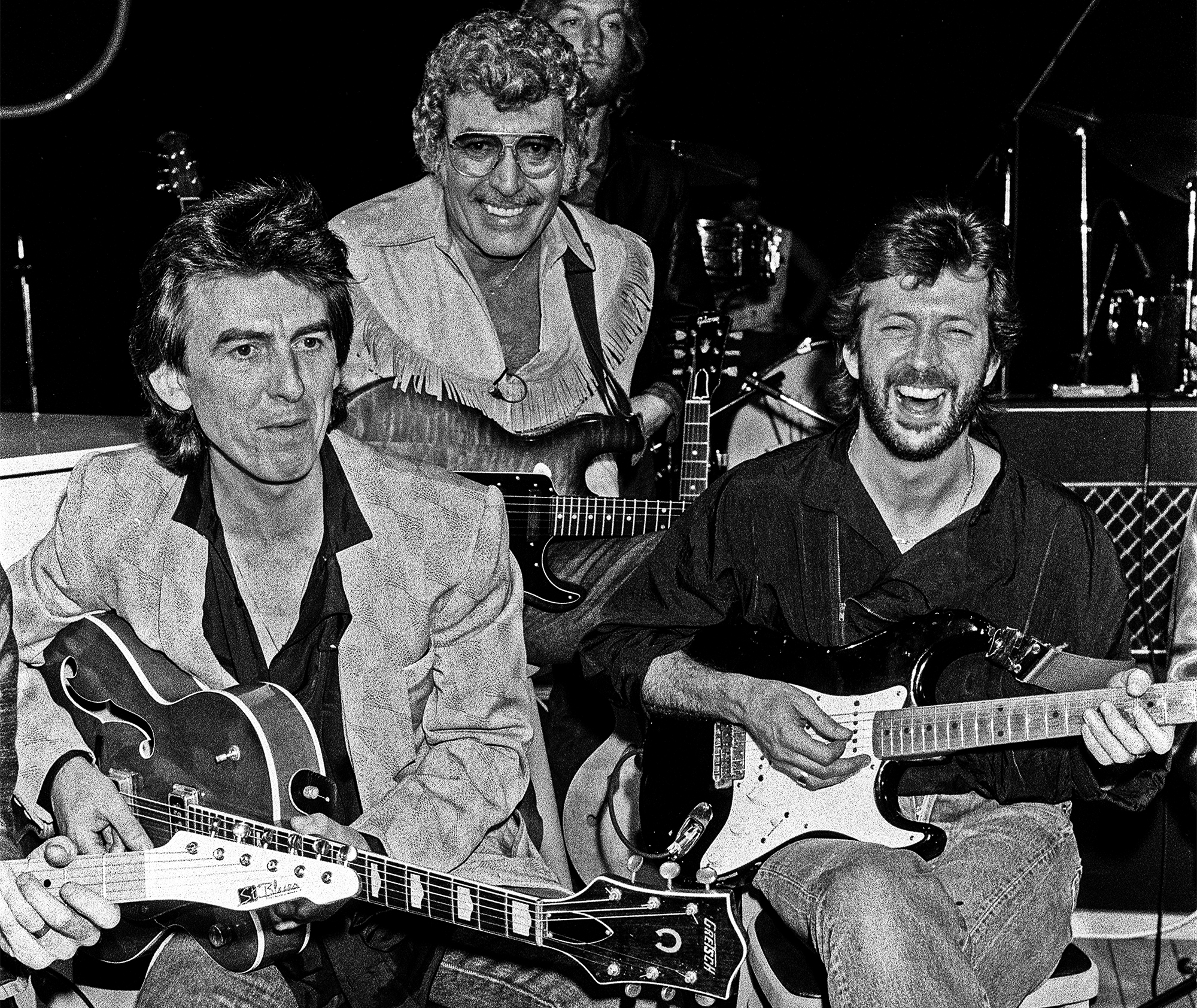

Over the next 36 years, until his death in 1998, he carried on playing bars, cutting dozens of albums and sharing stages with artists who revered him, including Eric Clapton, John Fogerty, Tom Petty, Joe Walsh and his old admirers Harrison, McCartney and Ringo Starr. He appreciated that his music had the power to inspire other guitarists to excel at their craft.

“Rockabilly’s simple music, but it’s not that easy to play,” he told Musician. “Rockabilly music gets under the skin, gets inside the ear and stays. You are part of that song. If it’s real, it’ll move you some way or another. If you ain’t tappin’ your foot, you’re missin’ the boat. Might as well go on to the next club.”

Christopher Scapelliti is editor-in-chief of GuitarPlayer.com and the former editor of Guitar Player, the world’s longest-running guitar magazine, founded in 1967. In his extensive career, he has authored in-depth interviews with such guitarists as Pete Townshend, Slash, Billy Corgan, Jack White, Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren, and audio professionals including Beatles engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott. He is the co-author of Guitar Aficionado: The Collections: The Most Famous, Rare, and Valuable Guitars in the World, a founding editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine, and a former editor with Guitar World, Guitar for the Practicing Musician and Maximum Guitar. Apart from guitars, he maintains a collection of more than 30 vintage analog synthesizers.