“He goes, ‘I play a little. I'm a hillbilly.’ Whips out his flatpick, man, and wailed on it.” How a devastating childhood accident and chance encounters with legends helped Ry Cooder become one of guitar’s most influential stylists

The guitarist would help define the Rolling Stones’ late-‘60s shift to country rock and bring Cuban music to a global audience

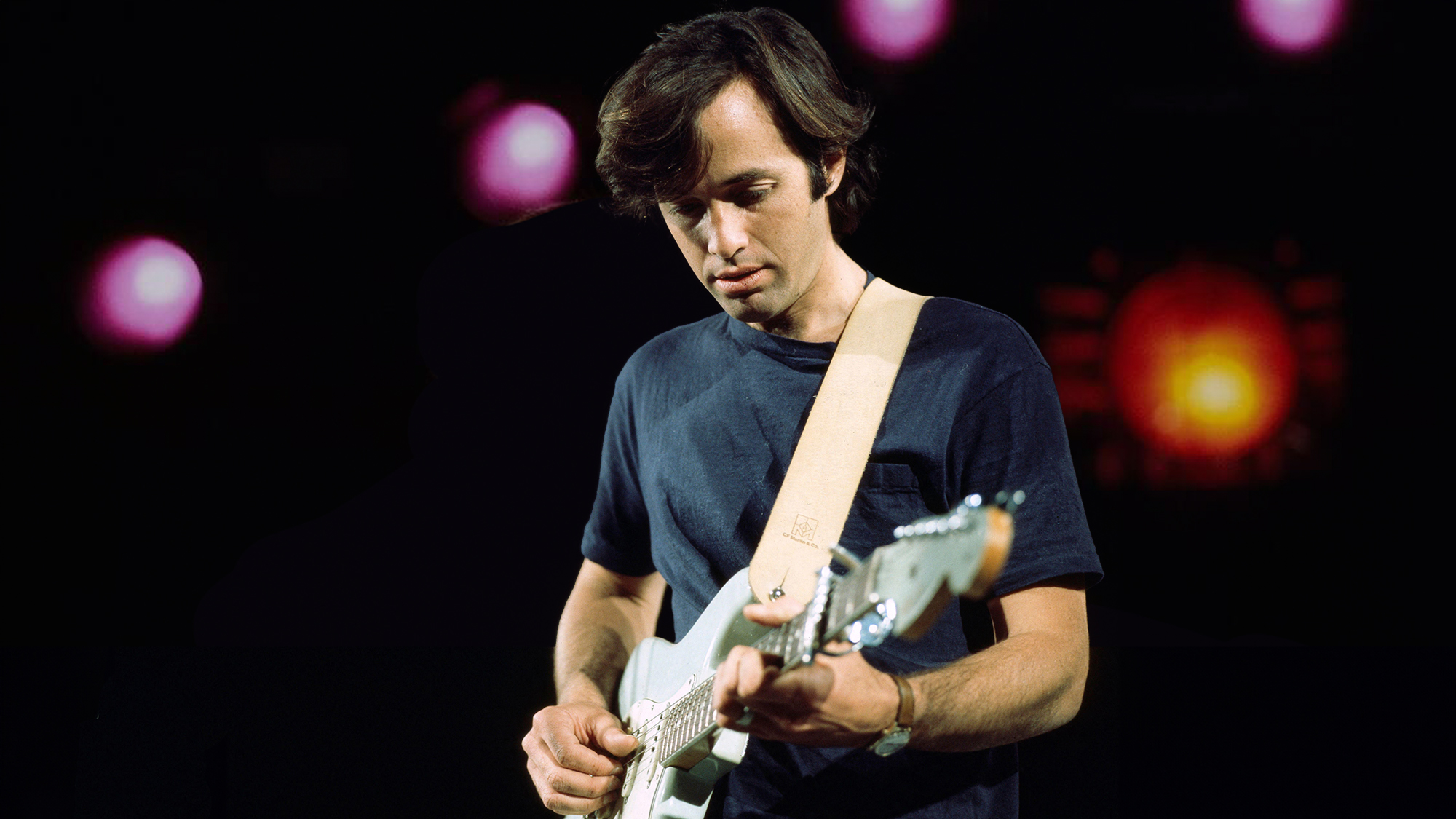

Ry Cooder stands as one of the most influential and idiosyncratic guitarists in American music. He’s a restless stylist whose work has reshaped how roots traditions are understood and applied in a modern context.

Cooder emerged in the late 1960s as a prodigiously knowledgeable student of blues, folk, country and early rock and roll. Although he wasn’t widely known among the record-buying public, he was in demand as a session guitarist, which is how he came to work with the Rolling Stones in 1969. Keith Richards has long credited Cooder’s open tunings and feel for American vernacular styles as a formative influence on the Rolling Stones’ turn toward roots-based songwriting in the late ’60s and early ’70s.

Beyond his impact on fellow electric and acoustic guitarists, Cooder’s own career defies easy categorization. His early solo albums reimagined traditional material with scholarly rigor and emotional immediacy, while his session work made him a first-call collaborator for artists ranging from Captain Beefheart to Randy Newman. In later decades, he expanded his scope further, becoming an acclaimed film composer and a cultural bridge-builder through projects such as Buena Vista Social Club, which helped bring Cuban music to a global audience.

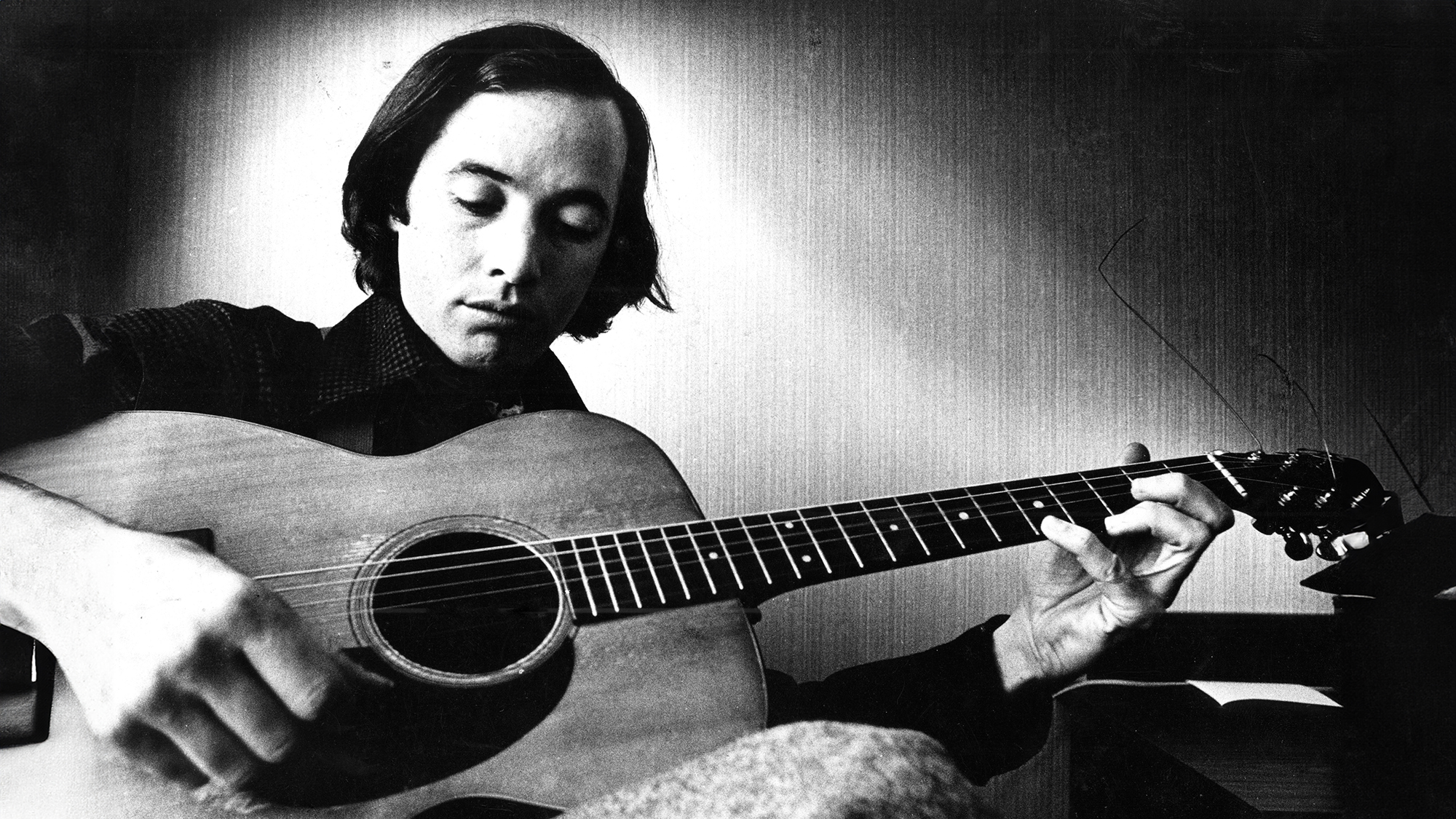

As he explained to Guitar Player in an interview that ran in our November 1993 issue, his introduction to guitar came almost as an act of grace following a devastating childhood accident.

“When I was about four and a half, I had this accident where I blinded myself in one eye with a kitchen knife. I had lots of little toy cars, and I was prying loose this part from one of them. The knife slipped and went right up into me, just sliced my eye right in half. Couldn’t do anything about it. Took it out.

I said, ‘What's that?’ And he said, ‘This is a guitar.’ Strum. Whoa! Right into the flesh.”

— Ry Cooder

“So I was despondent, quite withdrawn at that point. I just didn’t know what to do. I was a sensitive little kid. It was pretty rough. It was terrible trying to adjust and make sense out of such a horrendous thing, because kids don't think bad things are really going to happen, unless they're from El Salvador or South Central Los Angeles. They grow up knowing that down there, but your average little white kid, born and raised under more or less copacetic circumstances, cannot imagine personal danger like that. So I kind of went into a tailspin.

“Well, my folks were very good friends with this classical viola player who was blacklisted, Leo Breger. My dad's a big classical music fan, and they would listen to records and talk about conductors.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“So one night I’m laying in bed while they were out in the living room. I couldn’t sleep in those days; I was scared to go to sleep. He brings this thing in — I still have it — a Sears Silvertone tenor four-string. I’m laying on my back, and he puts it down on my stomach.

“I said, ‘What's that?’ And he said, ‘This is a guitar.’ Strum. Whoa! Right into the flesh.

“Hallelujah! Thank God! That was a rare example of some kind of intervention, of getting what you really need. And it went on from there. It was a way to make myself feel good.”

Cooder’s earliest lessons consisted of casual instruction from his father.

“My dad could play D, G and C chords and sing with the tunes, so I said, ‘What do I do?’ ‘Well, you put your hands here and put your hands there.’ So it gave me a place to go in my mind.

“Music was there, but how to get into it? How do you approach Handel or Beethoven? It wasn't the kind of household where you'd take professional piano or violin lessons. There wasn't that kind of vibe, and the guitar is, after all, do-it-yourself. You can make of it what you want to, and that's the great thing about it. It can be anything and everything to all kinds of people.”

These folk players weren't big talkers. ‘Where's that big-legged woman at?’ is what Bukka White was always asking.”

— Ry Cooder

He soon found inspiration from an unexpected encounter.

“One day I was waiting for the summer camp bus in front of my house. We lived by Douglas Aircraft, up here in Santa Monica, on the poor side of town. I had my guitar. I was going to take it to camp because I didn’t care for the activities. I thought if they would leave me alone, I'd sit under the tree and play.

“And this aircraft worker in his dungarees is walking along with his lunchbox. He sees me sitting there with a guitar, and he says, ‘Hi. You play that?’ And I said, ‘Yeah, kind of.’ And he goes, ‘I play a little. I’m a hillbilly.’ Whips out his flatpick, man, and wailed on it. Shit like I heard on the radio, Joe Maphis. This aircraft worker could rip and tear.

“He was somebody. I never knew his name; I never saw him again. I was too shy and too terrified to ask him who he was. I'll never forget that, though.

“When I was a kid, I was very attentive, and if I heard about somebody who was good or about a record, I'd run out. In those days, it was one-on-one, face-to-face. You could sit down with Jesse Fuller or Gary Davis or anybody.

“When I was little, I used to listen to the words on Woody Guthrie's Bound for Glory on Folkways. I wore it out. And then later we got to see these folk players, and they weren't big talkers. What did anybody ever say? ‘Where's that big-legged woman at?’ is what Bukka White was always asking.

“You know, ‘When am I going to get paid?’ says Brownie McGhee. It was just the atmosphere of the people. It was so amazing, what they radiate out.”

Christopher Scapelliti is editor-in-chief of GuitarPlayer.com and the former editor of Guitar Player, the world’s longest-running guitar magazine, founded in 1967. In his extensive career, he has authored in-depth interviews with such guitarists as Pete Townshend, Slash, Billy Corgan, Jack White, Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren, and audio professionals including Beatles engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott. He is the co-author of Guitar Aficionado: The Collections: The Most Famous, Rare, and Valuable Guitars in the World, a founding editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine, and a former editor with Guitar World, Guitar for the Practicing Musician and Maximum Guitar. Apart from guitars, he maintains a collection of more than 30 vintage analog synthesizers.