“We turned the Marshall up all the way, with the wah-wah and the midrange setting, and said, ‘That’s it. That’s the sound.’” In a rare interview, Barry Goudreau talks creating Boston’s smash debut and his ongoing rift with Tom Scholz

Boston's cofounding guitarist was sidelined on record by Scholz's desire to go it alone. "But we had tremendous success," he says, "more than we could ever hope for."

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The drive-by perception of Boston is that the band had but one guitarist: Tom Scholz. After all, Scholz authored most of Boston’s iconic songs. And he recorded most of the band’s music alone, in his basement.

But before the band had a record deal, sold millions of albums and launched massive world tours, Scholz was a keyboard player who was brought on by guitarist Barry Goudreau.

Goudreau recalls his musical aspirations of that time clearly.

“There was no grand plan,” he tells Guitar Player.

He did have chops, though. They were the only guitar skills in evidence on Boston’s first demos, created when the loose assemblage of musicians went by the name Mother’s Milk.

By the time Scholz assembled the six demo tracks that landed the band its deal with Epic Records, the keyboardist had become a guitarist and was the only one featured on the tape.

As for why that happened, Goudreau shrugs. “You’d have to ask Tom,” he says, but suggests economics might have played a role as well.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Whatever the reason, it’s not representative of the talents contained within Boston. View any of the group’s classic live performances — featuring Scholz on guitar and keys, Brad Delp on vocals, Fran Sheehan on bass, Sib Hashian on drums, and Goudreau on guitar — and you’ll find a group of musicians who had more than wholesale talent.

They had chemistry.

It wouldn’t be surprising if the band members found it aggravating to sit on the sidelines while Scholz worked his studio wizardry. But Goudreau is torn when asked about it.

“Yeah, it was frustrating,” Goudreau says. “But we had tremendous success, more than we could ever hope for.

“I did close to 400 shows with the band. We were one of the biggest concerts for several years in a row. It was enormous. I had a musical career because of it, so I’m certainly not going to look back and complain.

“Would I have liked to have played more? Sure. But it all worked out pretty well.”

Goudreau’s bigger gripe has to do with how the band was perceived. Boston is largely credited as the group that gave birth to “corporate rock,” a subgenre slicker and softer-edged than the hard rock that typified the 1970s.

Would I have liked to have played more? Sure. But it all worked out pretty well.”

— Barry Goudreau

“We hated that,” Goudreau says. “Part of the problem was that one of the first promotions for the first album was ‘Better Music Through Science,’ which had a picture of Tom in a space suit.”

“People took it as, ‘Oh, the album was written on a computer, and the record label controls the whole thing.’ But the label didn’t even know where the album was being recorded.“

Goudreau laughs at the memory.

“So, that couldn’t have been further from the truth.”

Regardless, Boston’s record hit pay dirt, with hits like "More Than a Feeling" — which beautifully merged acoustic and electric guitars — "Peace of Mind" and "Foreplay/Long Time." To this day, every track from the album receives airplay on classic rock radio.

But the lack of true band involvement and label pressure wore the group’s ranks down, leading to Scholz hitting the pause button in 1980. This led to Goudreau’s self-titled 1980 solo album, which sounded a whole lot like Boston, featured some of its members, including Brad Delp, and infamously promoted Goudreau as the “sound of Boston.”

Scholz wasn’t happy, and by 1981, he’d ousted the guitarist. While being sacked was painful, Goudreau has no regrets about making his solo record.

“That album was really important for me,” he says. “The fact that Brad and I were able to write the songs, pull them together, and record them so quickly was a real boost for me. It led to me having other projects and gave me the confidence to go ahead and have a career outside of Boston.”

That career continues by way of Barry Goudreau’s Engine Room. The group has released two albums to date: 2017’s Full Steam Ahead, and 2021’s The Road. Goudreau is still touring and representing Boston’s musical era. And he says there’s new music on the way.

“I’m still writing,” he says. “As long as people want to come and see my play, I’ll keep doing it. We have a lot of fun. I don’t see any reason why I would stop”

In Boston’s earliest days, you were on guitar and Tom was on keys. What led to his supplementing you on guitar?

I had just started college, and I started a band with a bass player I had been in a band with in high school. We weren’t serious about trying to do anything with it; we were just doing it to keep our hands in playing music and having some fun.

We didn’t have any grand design as to what we were going to do with it. We brought Tom in just to fill out the band. But when Tom came in, one of the first things we did was work out one of the first things he wrote, which was “Foreplay,” the instrumental piece that comes before “Longtime” on the Boston record.

Tom showed a real knack for writing when we started doing the demos, and we started to take it a little more seriously than we had before."

— Barry Goudreau

But we hadn’t been doing any writing at all. Tom really brought that to the band. And the next thing we did was “San Francisco Day,” which ended up becoming the song “Hitch a Ride.”

So Tom showed a real knack for writing when we started doing the demos, and we started to take it a little more seriously than we had before.

Tom played guitar on the demos that got Boston its record deal, but you handled most of, if not all, the guitars on the band’s initial demos. Did those early demos with you on guitar ever make it to the hands of record companies?

Oh, geez, that’s a good question. Yeah, some of it might have, but you know, it was very early on. The recordings were pretty crude. And again, Tom brought some real songwriting to it. Tom had a better grasp of the songwriting than we did. We’ll put it that way.

It's hard to believe that Boston was rejected so many times by labels like RCA, Atlantic and even Epic, which eventually signed the group. Was it surprising to the band that you had so much trouble getting a deal for a while?

Actually, it was a very long while. [laughs] I think a lot of it was that record companies are always looking to replicate something that’s already been successful. The Boston demos were very different from everything else that was going on, and I think that led them to steer away from it.

Of course, after Boston became super successful, everybody was looking for something that was just like Boston. They were chasing their tails, I guess. [laughs]

Is it true that the audition that got Boston signed to Epic Records took place in Aerosmith’s rehearsal space?

That is true. The record company had heard the demo and said, “Well, if you can replicate the demo live, we’re ready to go ahead with it.’ So, yeah, Aerosmith had a rehearsal space, and we went in there to do the showcase. It was actually just a couple of record execs.

Did the labels that rejected you give the band advice or feedback that led to you breaking through with Epic?

No, it was pretty much a standard rejection letter. You know, “Thank you for your submission. We’re not interested at this time.” None of them really gave any input as to what they might be looking for.

But Lennie Petze, who was one of the people at the label who got involved with us early on, had the initial rejection letter on the wall in his office, kind of making a point to the rest of the staff that mistakes happen. [Petze was Epic’s director of East Coast A&R in 1975 and eventually served the label as a senior vice president.]

The general consensus is that Tom crafted Boston’s guitar sound in his basement. But I’ve read that it might have been inspired by a Marshall amp of yours that had a bad transistor. Is there any truth to that?

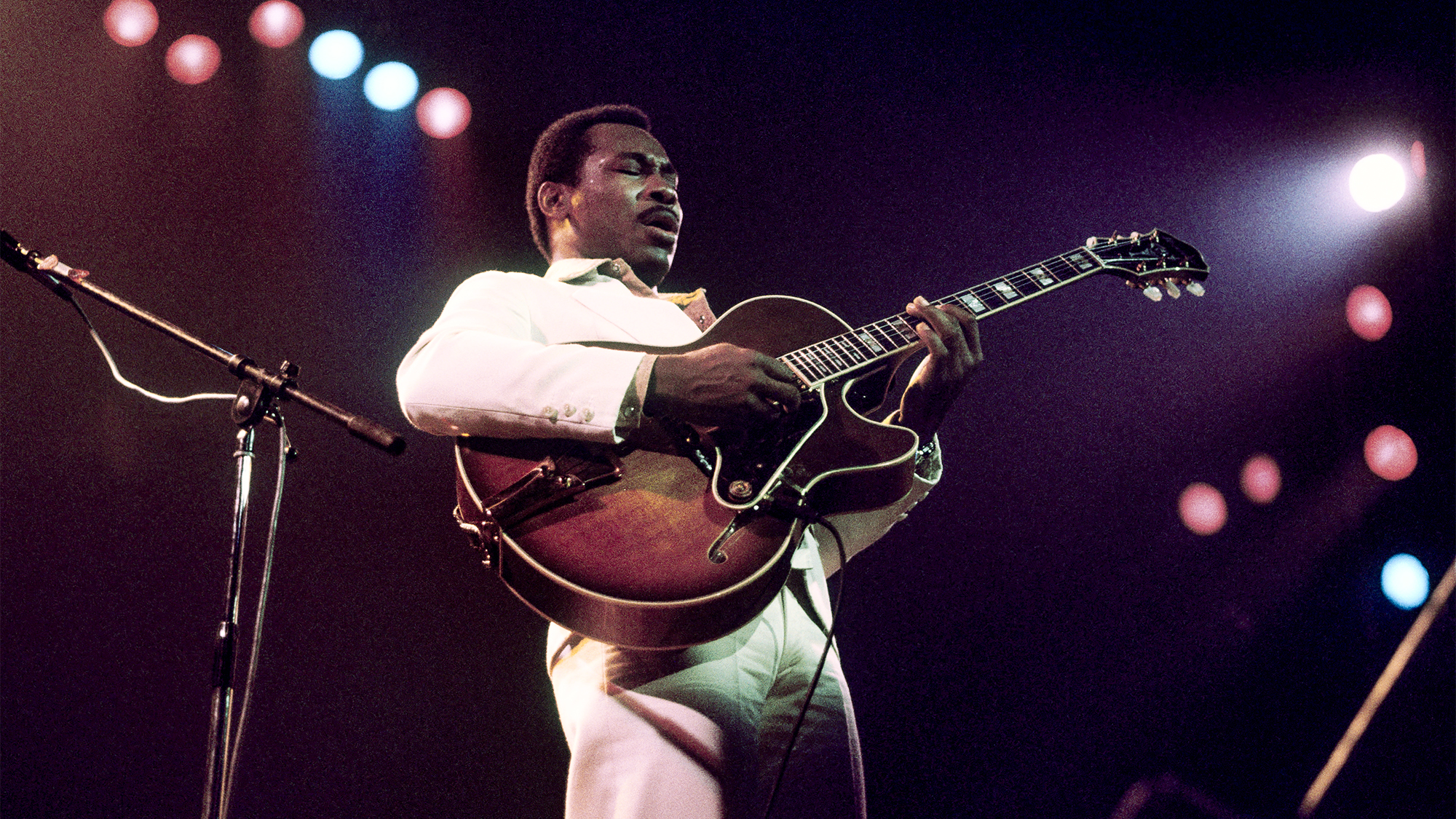

No. [laughs] Actually, I was a big fan of Jeff Beck. I saw the Jeff Beck Group when they came to Boston for the first time, and Jeff was playing a Les Paul through a Marshall through a wah-wah pedal, and he would set the wah-wah pedal in the middle, where it would boost the midrange.

Later on, Tom and I went to some other Jeff Beck shows, and when I bought my first Marshall amp, it was a ’69 Super Tremolo, I believe. I had that, and a wah-wah pedal, and we set it up in our rehearsal space, plugged it in, turned it up like a third of the way, and thought, That doesn’t sound right…

Jeff was playing a Les Paul through a Marshall through a wah-wah pedal, and he would set the wah-wah pedal in the middle, where it would boost the midrange."

— Barry Goudreau

Then we turned it up all the way, with the wah-wah pedal, and the midrange setting, and said, “That’s it. That’s the sound!” And the next time we got together, Tom had this black box with a big knob in the front — basically a rheostat [variable resistor], and put that between the amp and the speaker. We were able to turn the level down to where the amp was up all the way and you could get the gain from it.

At that point, there were no master volumes, and that was really the only way you could get the gain, you know, just by cranking the hell out of it, which was so painfully loud that it would blow you out of the room. [laughs]

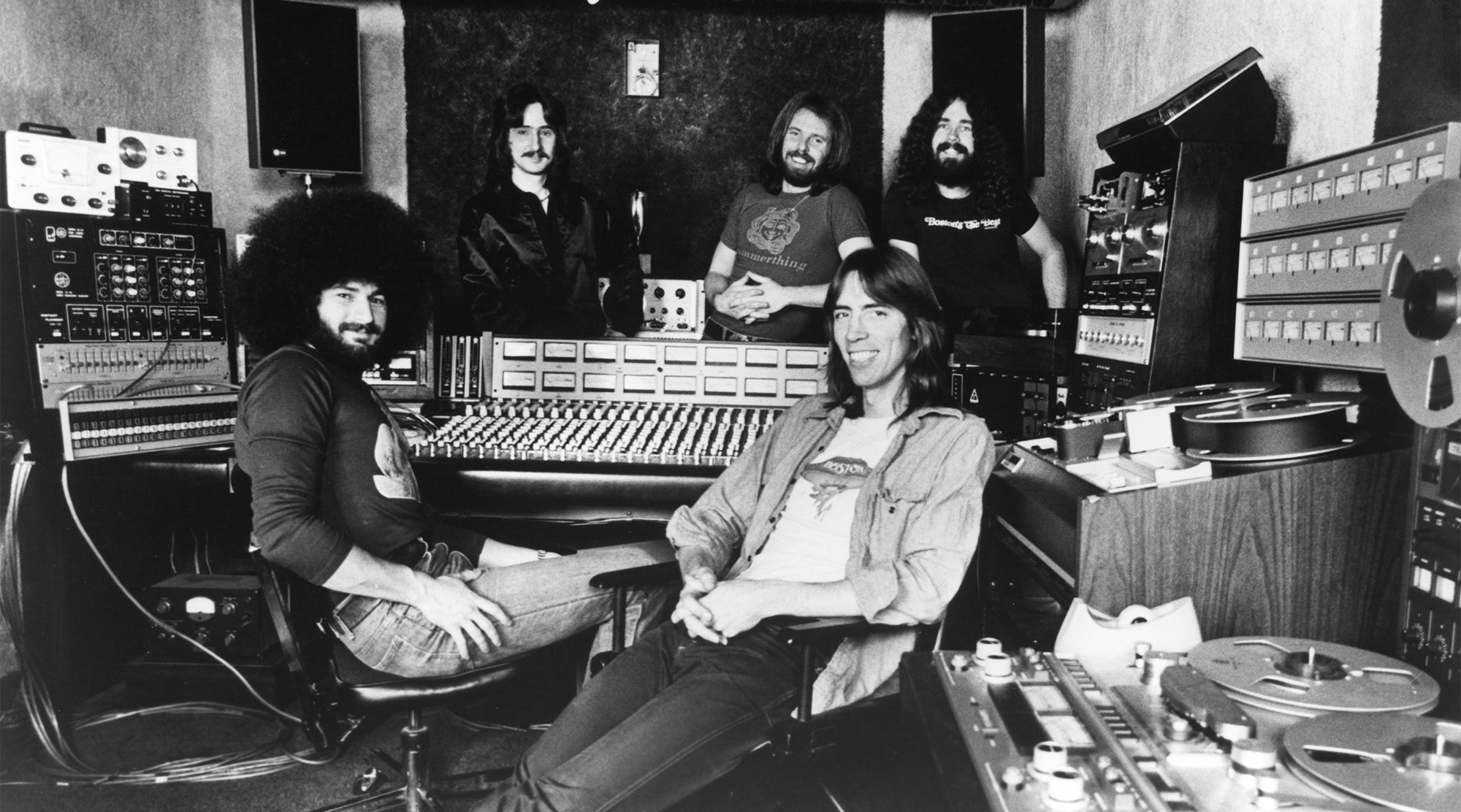

What led to the decision to record Boston’s first album in Tom’s basement alone rather than in a proper studio with a producer and the rest of the band?

I think it was economics. We went into the studio initially, but you know, it’s expensive going into a regular studio. Tom was the only one who had a real job; the rest of us were just scraping to get by. So I think it was economics more than anything.

He started to put some equipment together and obviously had a real knack for it. He would come home from work, go down into the studio, and not necessarily have the rest of us there. So you know, it kind of developed through all of that, I suppose.

I’m sure that Boston’s record label wasn’t thrilled with the idea of Tom recording in an isolated, uncontrolled environment like that.

If you listen to the demo that got us signed and then listen to the first record, they’re close to each other. But initially, the record company was not excited about the fact that Tom would be producing it, so to get around that, John Boylan came in. He did a lot of work for the label, and he kind of ran interference.

But you know, Tom stayed in his studio recording, and John was out in California. All of us, except for Tom, flew out to California and did some recording out there to give the label the impression that we were recording the album in L.A. with John Boylan. But Tom was just doing it in the basement, and pretty much replicating what he’d already done on the demo. And if you compare the two, they’re really close.

Tom played almost all the guitars on Boston’s debut, with two exceptions, one being “Foreplay/Longtime.” Clearly, you were more than competent, so why did Tom use you so sparingly?

I guess you’d have to ask Tom that as well. I would have been happy to have been there every day and just sat and waited for a chance to play. But Tom was comfortable working on his own. So when he was ready to bring me in, he brought me in. And that’s how I ended up playing on “Longtime.” I did all that playing in one session, actually.

Were you using the Marshall you mentioned earlier?

No. In fact the one thing I was really disappointed with is that I didn’t use that Marshall, which I bought and that he’d used on all those original recordings. When I went to record “Longtime,” I assumed I’d be playing through that Marshall. Instead, he had me playing through a Fender Champ. [laughs] I played with a Marshall distortion unit into the Champ amp. But obviously, it turned out pretty well.

You recorded the three solos in “Longtime” in one session. Were they all in one pass, or in multiple takes spliced together?

It was several different passes. Tom would call me and say, “I’m going to have you come in on this day to record.” And that day would come, and he’d say, “I’m not ready yet.” So I had time to keep working on it, and by the time I actually went in to record, I had pretty much mapped out the whole thing. So it wasn’t one pass through, but it was all done in one session with several passes put together.

You primarily played a Gibson SG live with Boston. Is that what you also used in the studio?

Yeah, it was a ’68 SG. I had gone to see Cream play back in 1968, and Eric Clapton was playing a red SG through a Marshall amp. I thought, I’ve got to have that, and went out and bought the SG. And that guitar is the one I used right through the first Boston tour until I was able to afford others.

I had gone to see Cream play back in 1968, and Eric Clapton was playing a red SG through a Marshall amp. I thought, I’ve got to have that."

— Barry Goudreau

The other track from Boston that you played on was “Let Me Take You Home Tonight.” How did that go down?

Actually, that’s one of the songs that we recorded out in Los Angeles with John Boylan. We did three cuts out there but only “Let Me Take You Home Tonight” made it onto the record. But yeah, that was the SG, and Brad played the slide on a Stratocaster. He was a huge Beatles fan and was trying to channel George Harrison.

Surely you had hopes of playing more on Boston’s second record, Don’t Look Back, but it didn’t happen. It’s clear Boston had chemistry live, so why did Tom become so restrictive in the studio? The rest of the band, you included, were really good players. It feels like a missed opportunity.

Again, you’d have to ask Tom about that. I think a lot of it was, obviously, the record label wanted another record as soon as possible. The deal that was signed called for pretty much a record every year, so we were already late on having another record. There was a lot of pressure on Tom to come up with it. I thought that would lead to him bringing us in to help out, but it actually turned out that he did more and more of it by himself.

After Don’t Look Back, Tom wanted a break and gave you a year to do whatever you wanted. You recorded a solo album, Barry Goudreau, featuring Brad on vocals and Sib on drums. And in all fairness, it sounds like Boston’s first two records and more “Boston-like” than anything Tom put together after you left the band.

Well, you know, John Boylan co-produced that with me. Obviously, he was involved in recording and mixing the first Boston record. I think that contributed a lot to the sound of my record.

Looking back on the record, I wish I had taken more time, but I was trying to work within a year’s timeframe that I was given. I listened to the record and felt as though if I spent more time on it, it could have been better developed. But it is what it is.

The promotional campaign for Barry Goudreau upset Tom. He felt it painted you as the sort of unknown “sound of Boston,” which wasn’t the intent, but it led to him firing you. Do you regret making the record because of what unfolded between you and Tom?

No, not really. Very early on, I did some songwriting, but once Tom really kicked in with his songwriting, I stepped back. He was doing such a good job, and I wasn’t trying to contribute anything writing-wise. So when there was an opportunity to record on my own, that was the first time I really concentrated on songwriting since the very early days.

Still, it led to your expulsion from Boston. Given Tom’s slow pace, your closeness with Brad and Sib, and the fact that you founded your band, was there a thought of continuing as Boston without Tom?

No, not really. But you know, when I left, Sib and Fran stayed on, and they were still working with Tom on the third record, Third Stage. My record came out in ’80, and we had a meeting at the beginning of ’81 where Tom announced that he wasn’t going to work with me anymore.

And at that meeting, Brad said, “Well, I’ll continue to record with you, and I’ll do another record, but I’m leaving the group.” So actually, Brad left Boston before the third record. Obviously, he sang on that record and toured on it, but he wasn’t officially a member of the band anymore.

My record came out in ’80, and we had a meeting at the beginning of ’81 where Tom announced that he wasn’t going to work with me anymore."

— Barry Goudreau

Looking back, is there anything you could have done differently, or wish you’d done differently, that would have resulted in a better outcome?

Well, hindsight is 20/20, as they say. If I would have changed anything, it would be to not have pushed to get my record out within the year timeframe that I was given. I think if I had laid back, and put more time into it, things might have turned out differently. But it doesn’t matter at this point.

Things between you and Tom have gotten very icy over the years. Is there a chance that you two will bury the hatchet?

Yeah, I don’t really see that happening. We ended up in federal court several years ago, so, you know, there’s a lot of bad blood there. I wouldn’t expect to be getting a call. Let’s put it that way.

Despite the bad blood, are you able to look back on your time in Boston through a positive lens?

Absolutely. We had such tremendous success so quickly. I mean… we had some really great years. It was a whole lot of fun. There was a lot of pressure to live up to expectations, but it was a really great time.

I look back with fond memories, and it gave me the ability to have a career outside of Boston, which I’m still pursuing. So I don’t look back with any bad feelings.

Andrew Daly is an iced-coffee-addicted, oddball Telecaster-playing, alfredo pasta-loving journalist from Long Island, NY, who, in addition to being a contributing writer for Guitar World, scribes for Rock Candy, Bass Player, Total Guitar, and Classic Rock History. Andrew has interviewed favorites like Ace Frehley, Johnny Marr, Vito Bratta, Bruce Kulick, Joe Perry, Brad Whitford, Rich Robinson, and Paul Stanley, while his all-time favorite (rhythm player), Keith Richards, continues to elude him.