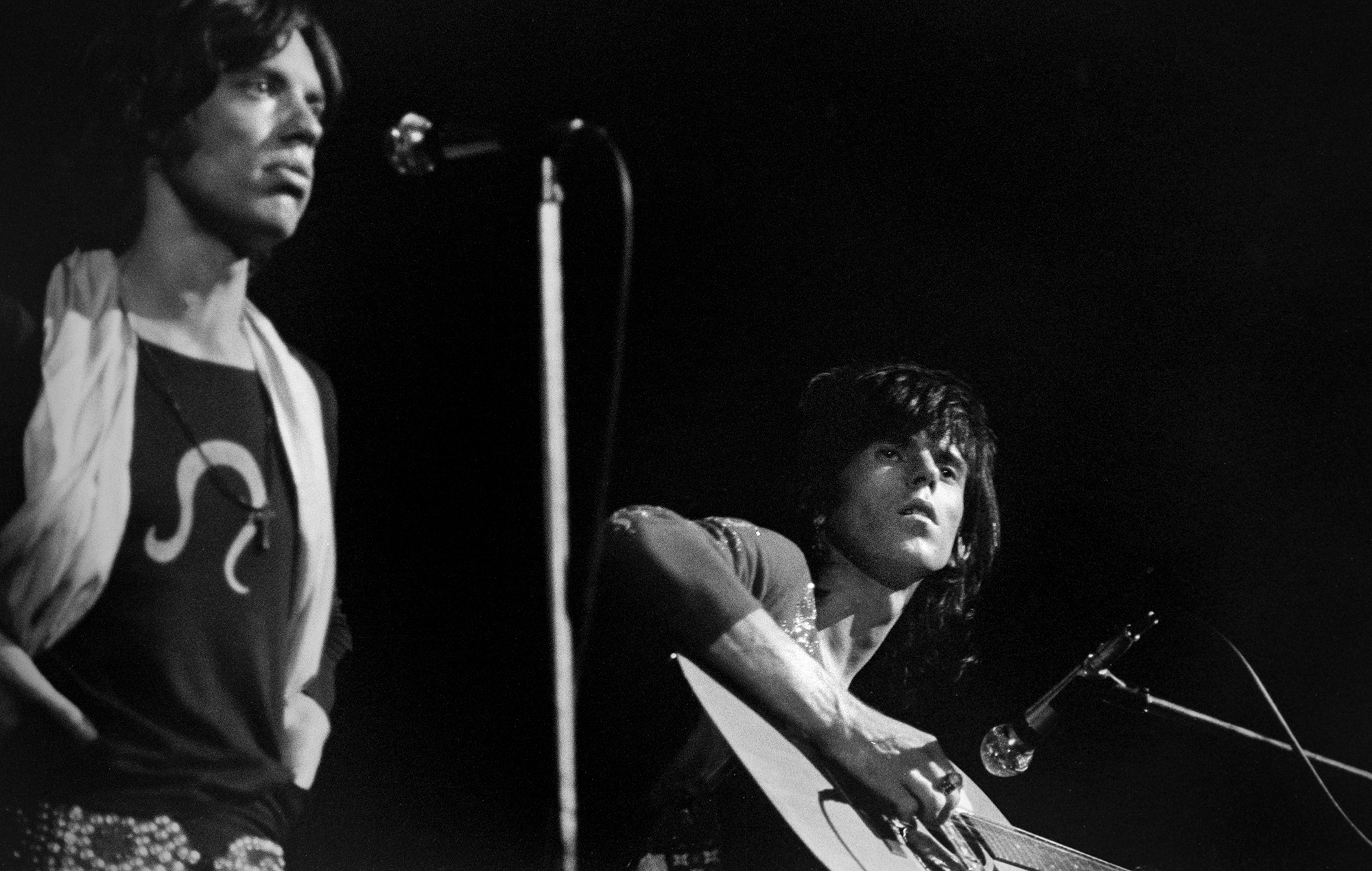

“We were forcing acoustic guitars through a cassette player. What came out was electric as hell.” Keith Richards on how acoustic guitars, alternate tunings and a cassette recorder revived the Rolling Stones with a pair of classic hits

Amid the turmoil of drug busts and music missteps in 1967, Richards dug deeper into acoustic guitar and pushed the Stones in a new direction

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

“There are times when an acoustic guitar will make a track,” Keith Richards says. “You’ll be despairing, nothing working, hashing away. Take 43 on electric guitar, and somebody will say, ‘Why don’t you try it on acoustic?’

“And you will try it one more time and you’ve got it.”

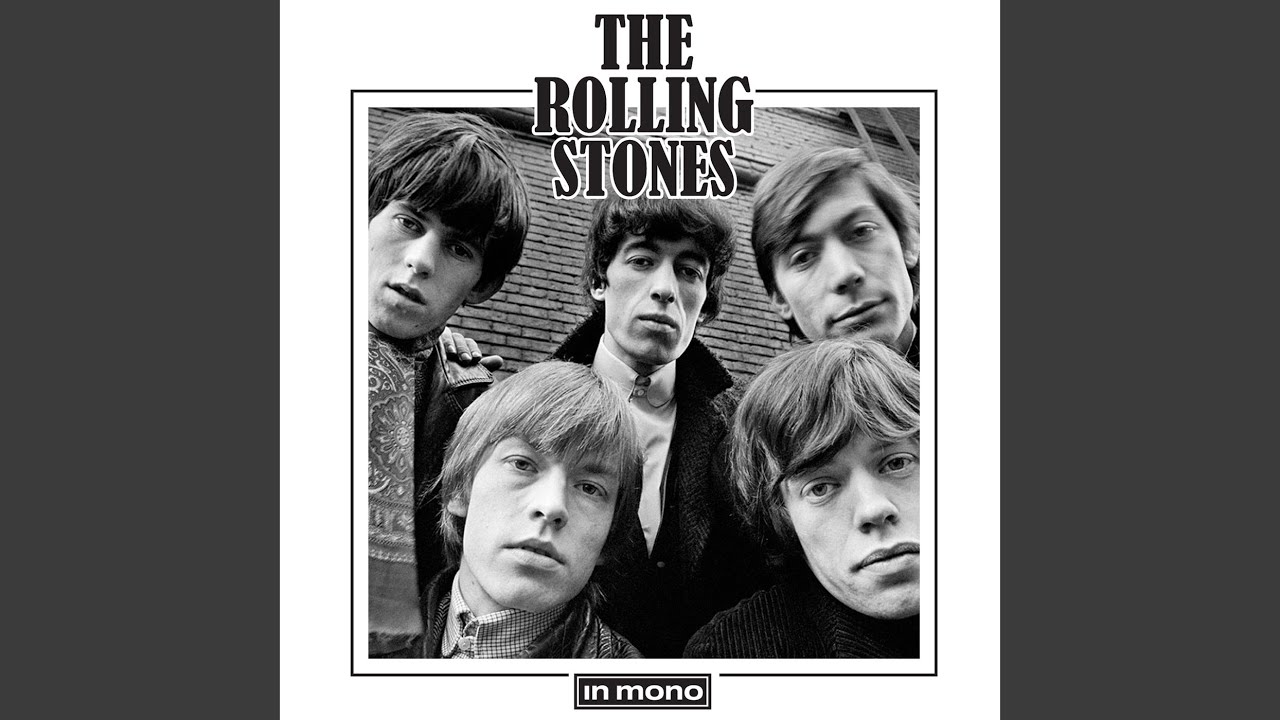

Although he’s famous for playing a range of electric guitars — from Gibson Les Pauls to Fender Telecasters to Strats — acoustic guitar has always proved to be the perfect foil to Keith Richards’ electric work. The instrument has been part of the Stones’ musical makeup from early on, and it became a key part of the roots-rock sound the Rolling Stones began cultivating in 1968, around the time they began work on Beggar’s Banquet.

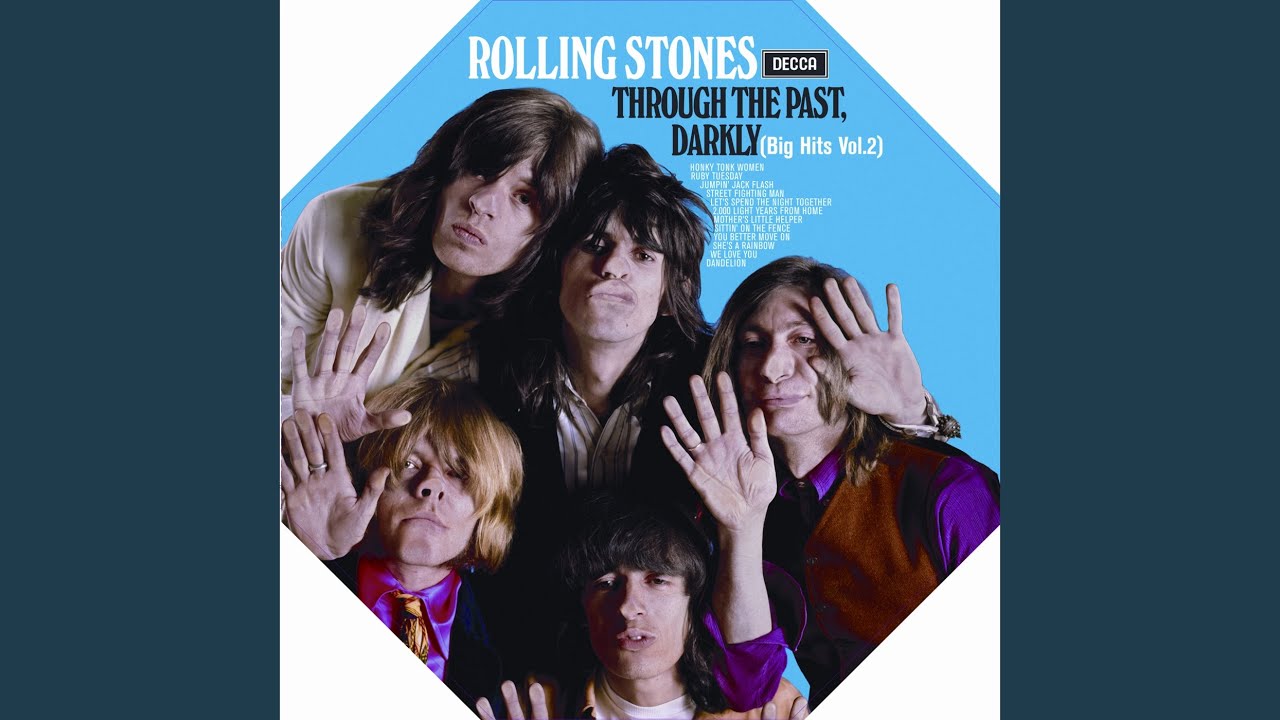

The timing is significant in Stones history. The group had hit a new plateau with the release of Between the Buttons in January 1967. The album produced a pair of chart-topping U.S. hits, “Ruby Tuesday” and “Let’s Spend the Night Together,” released together as a double A-side single, and showed musical growth with its range of styles, including baroque rock and psychedelia.

But the album’s release was followed by a period of creative confusion. Shortly afterward, Richards, Mick Jagger and guitarist Brian Jones were each arrested on drug charges. Between appearances in court and jail terms, the group was rarely together in the studio at the same time

Through it all, the Stones attempted to keep up with the growing psychedelic rock movement by recording Their Satanic Majesties Request, an album that, despite its many brilliant moments and songs, was considered a failure upon its release in December of that year.

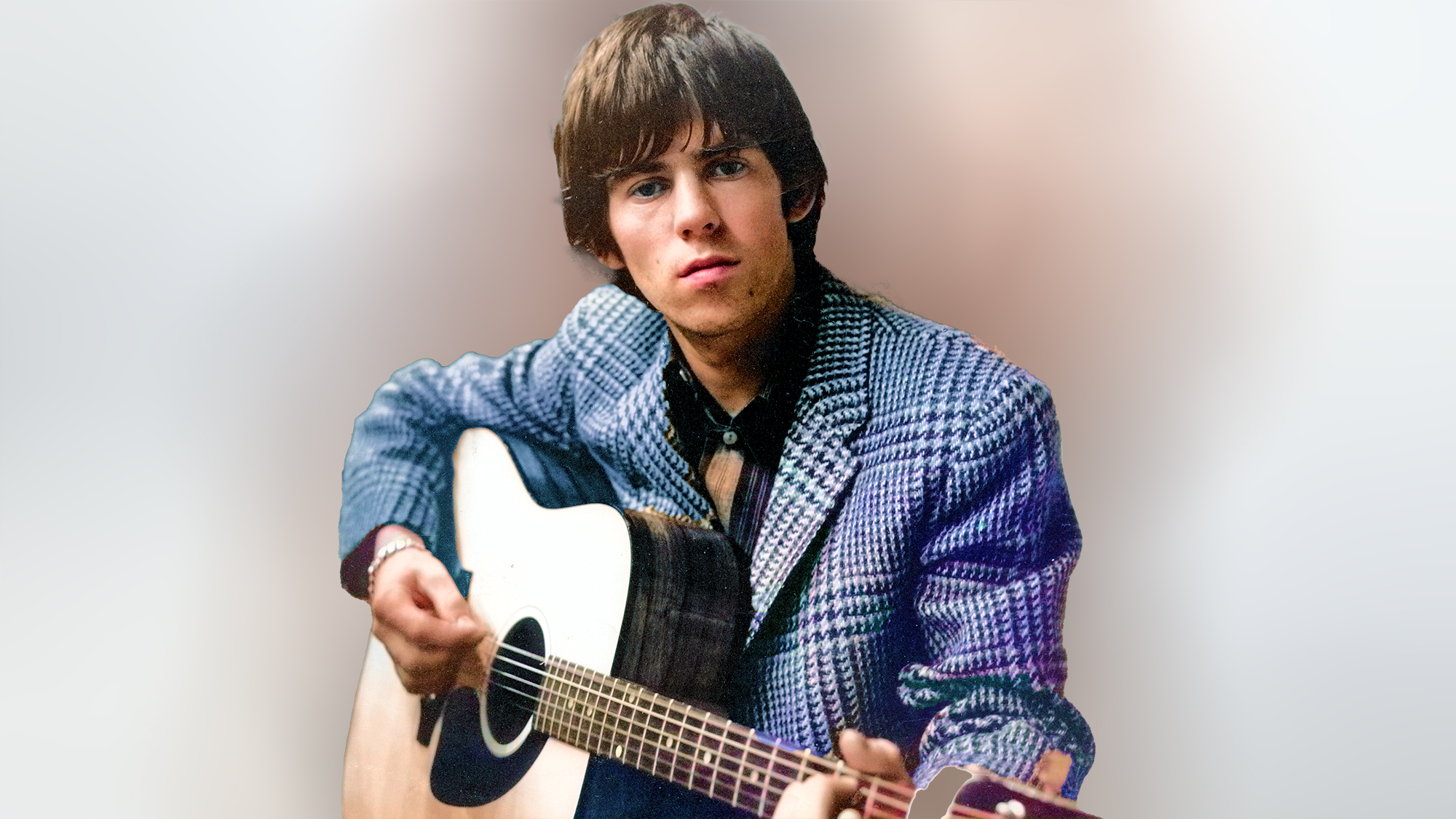

The Stones needed a creative reset. As it happened, Richards had spent much of the previous year digging into old blues recordings from the 1920s and ’30s. That led him to explore open tunings, marking the start of his journey to the five-string open G tuning he’s used since around late 1968/’69.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“I started to use open tunings on Beggars Banquet,” he told us in his cover feature in the November 1977 issue. “During that long recording lay-off after Between the Buttons, I got rather bored with what I was playing on guitar—maybe because we weren't working, and it was part of that frustration of stopping after all those years, and suddenly having nothing to do. So my playing sort of stopped, along with me.

“Then I started looking into some ‘20s and ’30s blues records. Slowly, I began to realize that a lot of them were in very strange tunings. These guys would pick up a guitar, and a lot of times it would be tuned a certain way, and that's how they'd learn to play it. It might be some amazing sort of a mode, some strange thing.

“And that's why for years you could have been trying to figure out how some guy does this lick, and then you realize that he has this one string that is supposed to be up high, and he has it tuned down an octave lower.

That eventually led him to try open-D tuning (low to high, D A D F# A D) “which I used on Beggars Banquet,” he said.

Around the same time, Richards discovered a new tool that helped him capture the sort of gritty, low-fi sound of those early blues records: the compact cassette recorder. Created by Phillips and released to the public in 1964, the technology was still best suited to voice recording at the time, but the results suited Richards just fine.

"I’d discovered a new sound I could get out of acoustic guitar,” he wrote in his book, Life. “That grinding dirty sound came out of these crummy little motels where the only thing you had to record with was this new invention called the cassette recorder....

I started looking into some ‘20s and ’30s blues records. Slowly, I began to realize that a lot of them were in very strange tunings.”

— Keith Richards

“Playing acoustic, you'd overload the Philips cassette player to the point of distortion so that when it played back it was effectively an electric guitar. You were using the cassette player as pickup and amplifier at the same time. We were forcing acoustic guitars through a cassette player, and what came out the other end was electric as hell.”

The combination of acoustic guitar, open tunings and the cassette recorder as signal processor came together in April 1968 with the recording of two new songs: “Jumpin’ Jack Flash” and “Street Fighting Man.”

As Richards recalls, he used a Gibson Hummingbird tuned to open D (low to high, D A D F# A D) and capoed “to get that really tight sound. And there was another [acoustic] guitar over the top of that, but tuned to Nashville tuning. I learned that from somebody in George Jones' band in San Antonio in [1964]… Both acoustics were put through a Phillips cassette recorder. Just jam the mic right in the guitar and play it back through an extension speaker.”

While “Jumpin’ Jack Flash” features leads (played by Richards) and rhythm (played by Jones) on electric guitar, “‘Street Fighting Man’ was all acoustic guitars,” Richards tells Guitar Player. “Everything there was totally acoustic. The only electric instrument on there is the bass guitar, which I overdubbed afterwards.”

But Richards’ acoustic guitar treatment was just one part of the track’s magic. It owes much as well to Charlie Watts’ drum kit of choice.

“Charlie was playing his little 1930s drummer’s practice kit,” Keith recalls. “It was all sort of built into a little attaché case, so some drummer who was going to his gig on the train could sort of open it up—with two little things about the size of small tambourines without the bells on them, and the skin was stretched over that.

“And he'd set up this little cymbal, and this little high-hat would unfold. Charlie sat right in front of the microphone with it. I mean, this drum sounds massive. When you're recording, the size of things has got nothing to do with it. It’s how you record them.

I started on acoustic guitar, and you have to recognize what it's got to offer.”

— Keith Richards

At the same time, Richards acknowledges that acoustic guitar is another tool and that much of its sound is down to what you do with it, as he proved on “Jumpin’ Jack Flash” and “Street Fighting Man.”

“Well, I started on acoustic guitar, and you have to recognize what it's got to offer,” he says. “But also you can't say it's an acoustic guitar sound, actually, because with the cassette player and then a microphone and then the tape, really it's just a different process of electrifying it.

“You see, I couldn't have done that song or that record in that way with a straight electric or the sustain would have been too much. It would have flooded too much. The reason I did that one like that was because I already had the sound right there on the guitar before we recorded. I just loved it. and when I wrote the thing I thought, I’m not going to get a better sound than this.”

Christopher Scapelliti is editor-in-chief of GuitarPlayer.com and the former editor of Guitar Player, the world’s longest-running guitar magazine, founded in 1967. In his extensive career, he has authored in-depth interviews with such guitarists as Pete Townshend, Slash, Billy Corgan, Jack White, Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren, and audio professionals including Beatles engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott. He is the co-author of Guitar Aficionado: The Collections: The Most Famous, Rare, and Valuable Guitars in the World, a founding editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine, and a former editor with Guitar World, Guitar for the Practicing Musician and Maximum Guitar. Apart from guitars, he maintains a collection of more than 30 vintage analog synthesizers.