“I used to get into terrible trouble with Dave by trying to add too much piano to what he laid down.” Ray Davies on the origins of the Kinks' “You Really Got Me” — and what guitarists get wrong about serving the song

Davies said the track began life as a jazz tune until his brother got a hold of it

For a song that’s two minutes and change in length, “You Really Got Me” has kept guitarists entertained for decades with stories about its creation and recording.

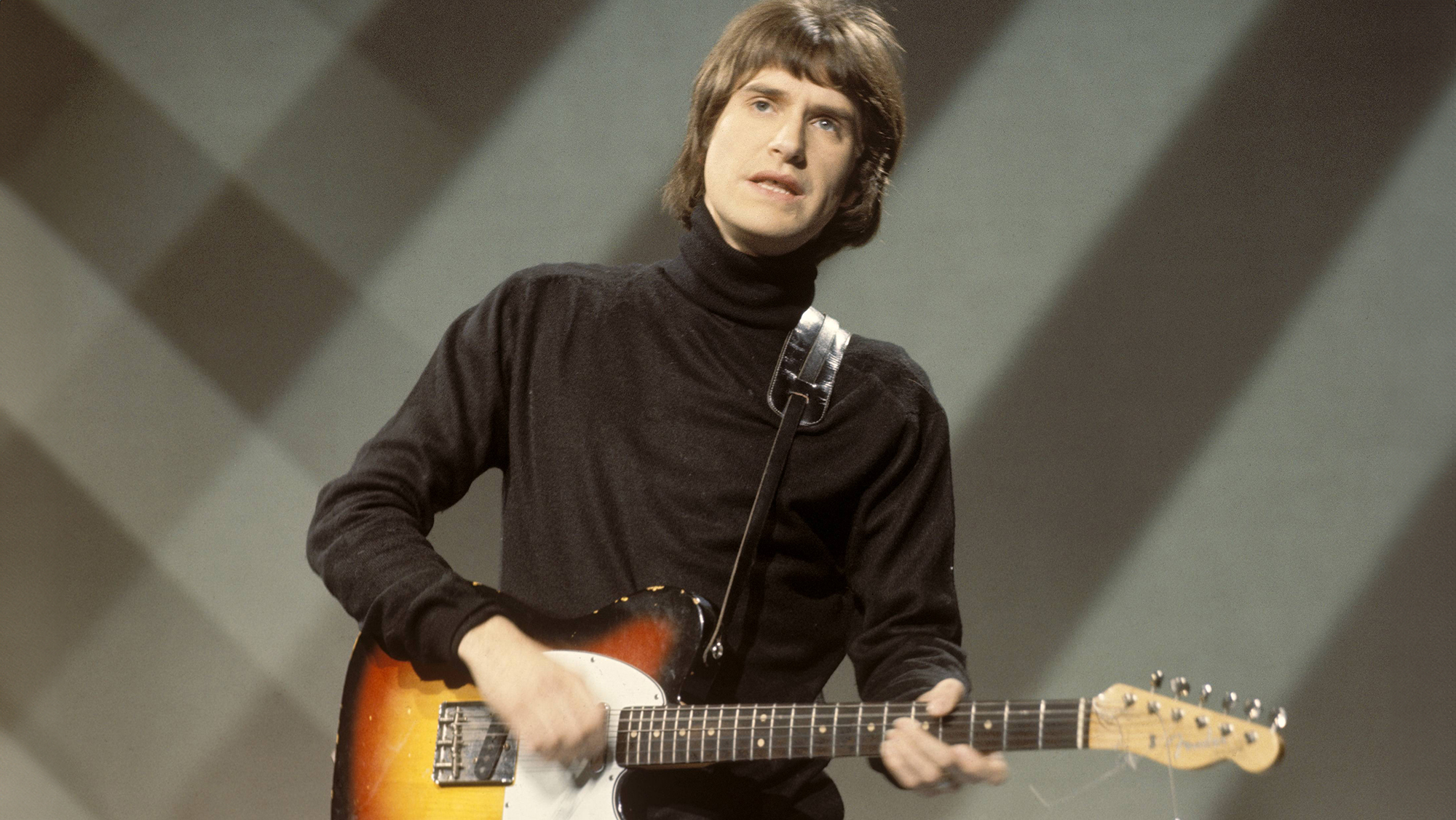

The 1964 Kinks classic rose to the top of the news chain recently when guitarist Dave Davies was forced to defend his electric guitar solo on the song against claims Jimmy Page performed it as a session musician.

"No, it's not true,” Davies told Ultimate-Guitar.com. "He was there at the sessions, because I thought they worried that we couldn't play! There's no animosity, and Jimmy was a nice guy, we got on well with him. I hardly said anything to him."

There’s good reason why “You Really Got Me” remains relevant some 60 years after its birth. It’s celebrated as the song that presaged hard rock and put power chords on the map. It also made a strong case for distortion, which Davies achieved by expertly slicing the speaker of his Elpico AC55 combo with a razor blade.

The song not only fired up Pete Townshend — who paid homage to it with the Who’s “I Can’t Explain” — but raised both Page’s and Jeff Beck’s awareness of distortion’s transformative power.

I wanted it to be a jazz-type tune, because that's what I liked at the time. It’s written originally around a sax line.”

— Ray Davies

All of which is pretty surprising for a song that got its start on the piano. Ray Davies wrote it on that instrument in the front room of the Davies’ home sometime between March 9 and 12, 1964. It was originally conceived as a jazz-style tune and was among Ray’s earliest tunes — “one of the first five I ever came up with,” he says.

From the start, he intended the song to be laidback, with a saxophone handling the distinctive riff.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“I wanted it to be a jazz-type tune, because that's what I liked at the time,” Ray said. “It’s written originally around a sax line ...”

But Dave had other ideas.

“Dave ended up playing the sax line in fuzz guitar and it took the song a step further.”

As Ray explained to Guitar Player in September 1998 issue, his songs often came to life on the piano.

“That happened a lot with me,” he said. “But you see, if I wrote a song on piano, I learned not to reintroduce the piano once Dave put his guitar on a track.

“I used to get into terrible trouble with Dave by trying to add too much piano to what he laid down.”

The Davies brothers were famous for their battles, and one can only assume Ray was careful not to provoke Dave. Besides, he said, his brother’s sense of arrangement was correct.

He said it detracted from the purity of the sound of the guitar—which is right, in a strange way.”

— Ray Davies

“He said it detracted from the purity of the sound of the guitar—which is right, in a strange way. When you try to put the two together, the dynamics are not quite right.”

For evidence, Ray pointed to what he called “those ‘only in America’ records that happened a lot in the '80s, where there was a horrible marriage of keyboard technology and heavy-metal guitar. I found that to be obtrusive and degrading to the music.”

All the same, Ray said part of the problem has to do with guitarists and their need to dominate.

“Deservedly or not, guitarists have a bit of a reputation for letting their egos hammer a song into submission,” he said. “A good guitar player must be able to edit, cut things down, and sacrifice his or her own playing for what the song has to do. '

“Think about that. What are you doing here? Are you going on an ego trip for, say, 24 bars, or are you trying to develop the melody? If you suddenly drop in — guitar solo! — and play something that's unconnected with what's happening in the piece, you're just playing a lot of good crap rather than performing something that grows with the music.

“The great players have an instinctive logic that tells them, ‘Maybe that's over the top.’”

Dave Davies might agree with that, particularly when it comes to Van Halen’s take on “You Really Got Me,” which he claimed “misses the point of the meaning of the song.” In fact, the one guitarist who absolutely floored him was Leslie West, whom he called “a great and underrated guitar player.” Indeed, West was celebrated for not only his signature guitar tone but his melodicism and his knowledge of how not to overcook a solo (as Joe Bonamassa recalled).

In related news, the Kinks have released the final part of their 60th anniversary anthology series on July 11. The Journey – Part 3 covers their RCA/Arista period, spanning from 1977 to 1984.

Elizabeth Swann is a devoted follower of prog-folk and has reported on the scene from far-flung places around the globe for Prog, Wired and Popular Mechanics She treasures her collection of rare live Bert Jansch and John Renbourn reel-to-reel recordings and souvenir teaspoons collected from her travels through the Appalachians. When she’s not leaning over her Stella 12-string acoustic, she’s probably bent over her workbench with a soldering iron, modding gear.