Explore the Inventive Musical Mastery of Tom Scholz

A celebration of the artistry and ingenuity of Boston’s renaissance man

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

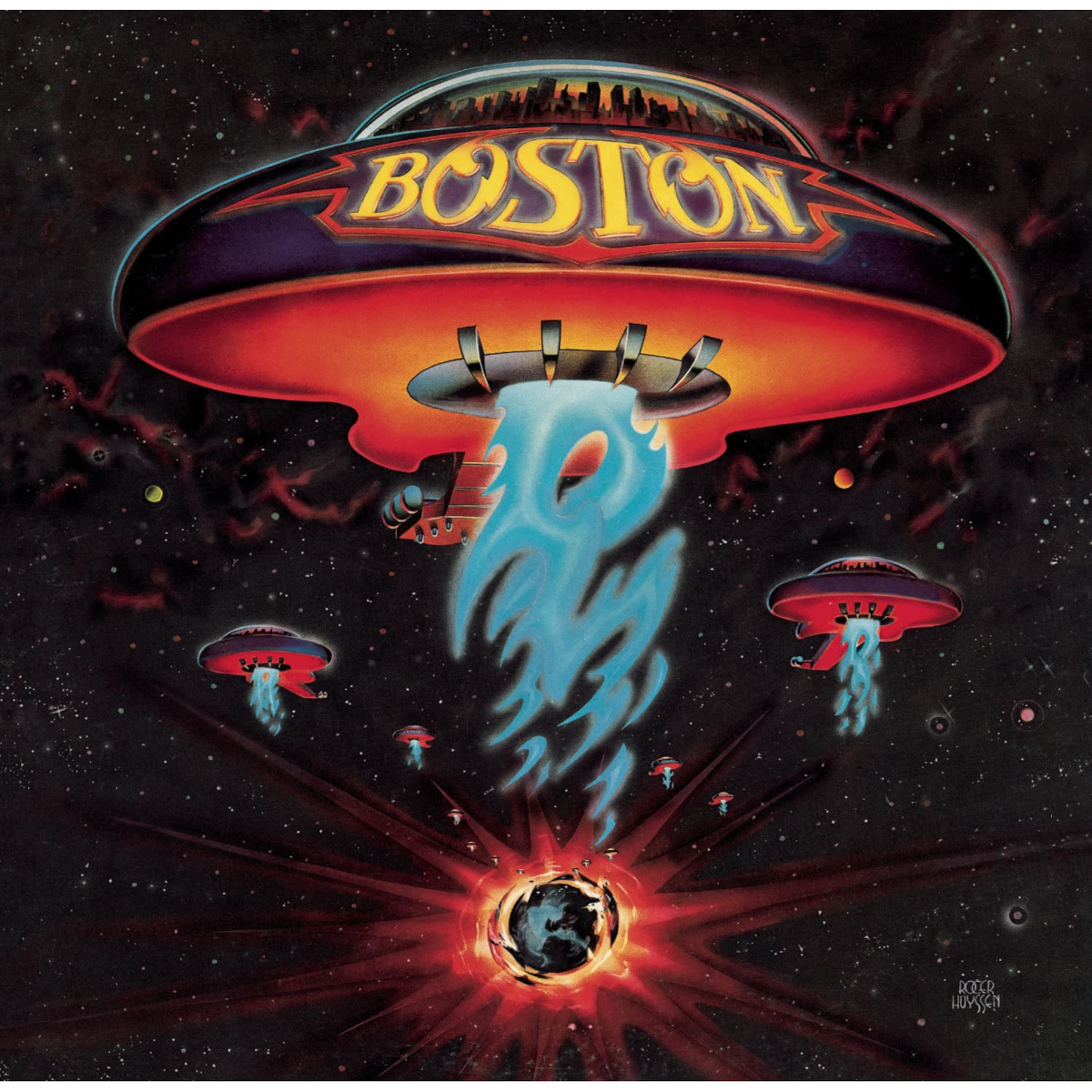

When I was 10 years old, I began taking guitar lessons with Bob, a teacher who would become my all-time favorite. Sadly, after one year, Bob left to pursue life as a truck driver, and our paths would never cross again. True to form, though, at our final lesson, he gave me a couple of his favorite albums, one of which was Boston’s 1976 self-titled debut. I can still remember putting the vinyl on my turntable and instantly being mesmerized.

Years later, things would come full circle when, as a professional music transcriber, I had the opportunity to create the official note-for note guitar tab books for Boston and its 1978 follow-up, Don’t Look Back.

I may have known Bob for only a year, but the records he left me – which are arguably Boston’s most classic and enduring albums – continue to fascinate and inspire me, and they’ll be our focus throughout this lesson.

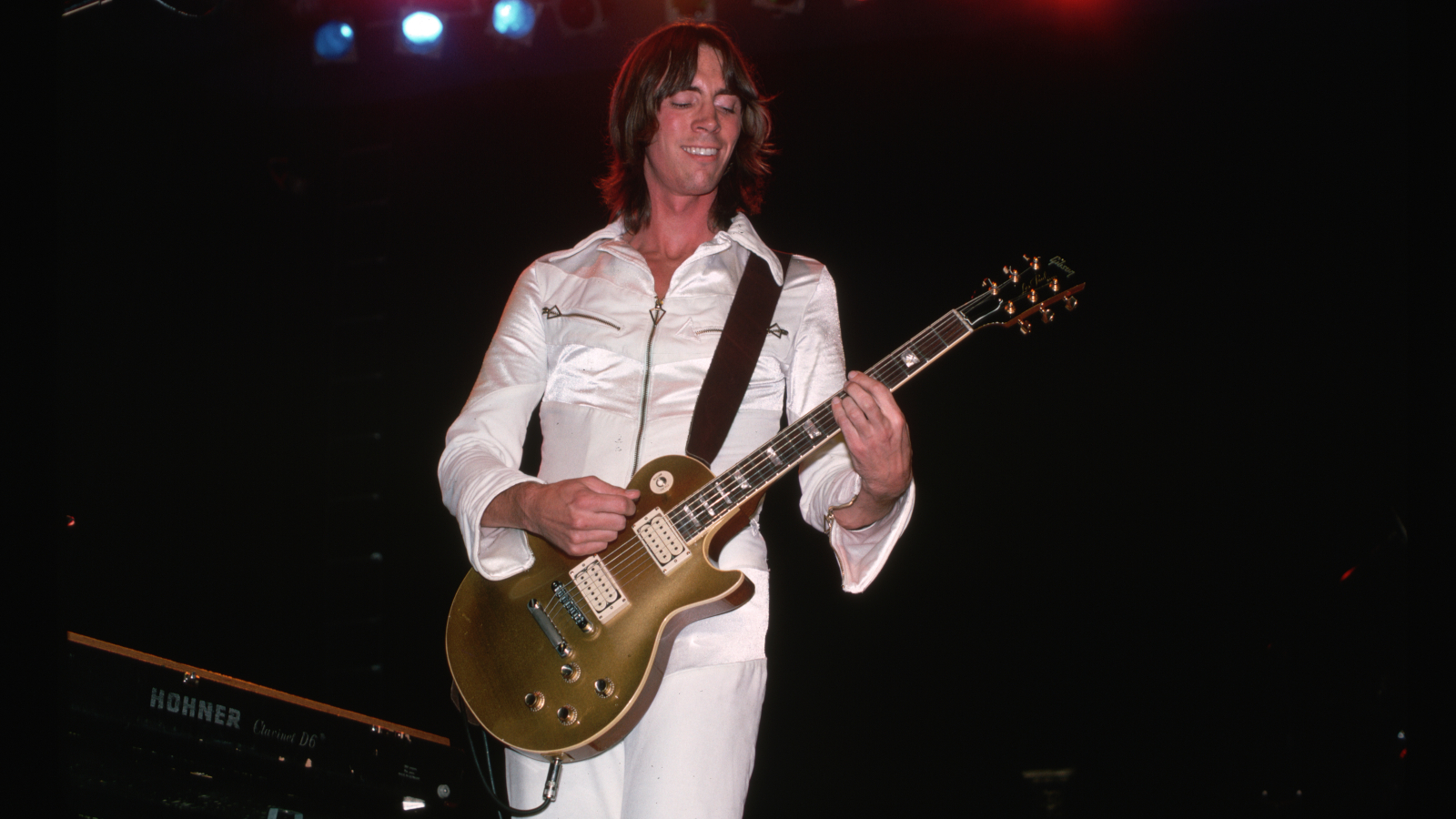

Boston is the musical brainchild of songwriter and multi-instrumentalist Tom Scholz, who also has a background in electrical engineering and is an accomplished inventor. As a young man, Scholz attended Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), and later worked as an engineer for Polaroid, a corporation best known for its instant film and cameras.

This engineering prowess enabled Scholz to design and build his own outboard effects and pedals, all of which would become the foundation of Boston’s signature sound.

Musically, Scholz melded searing rock guitar with songs you might feel you’ve known for years after having heard them only once. The hallmarks of his style are soaring melodies and harmonies – vocal harmonies, yes – but the core of Scholz’s sound lies in his use of layered harmony lead guitars.

Other guitarists had already pursued this path, most notably Queen’s Brian May, but Scholz took a simpler approach. Whereas May would sometimes layer as many as five or six electric guitars to create a virtual guitar choir, Scholz almost exclusively used just two.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

But it was the guitarist’s knack for writing catchy, singable guitar melodies that set him apart. These melodies had much in common with the ones he would write for Boston’s lead singer Brad Delp, as they were quite vocal-like, complete with expressive bends and Scholz’s striking vibrato.

We’ll explore in depth how he created his harmony magic a bit later.

But first, how did he get that guitar sound? The fact is, Scholz’s engineering skills enabled him to design and build his own effects gear when he simply couldn’t find another way to create the sounds in his head.

In the 1970s, he designed what would later be mass-produced as the Rockman, a handheld headphone amp housed in the style of the then-new Sony “Walkman” portable cassette player. The Rockman was marketed in 1982 by Scholz Research & Development (SR&D), the company Tom founded in 1980.

One of his proudest moments as an engineer came when he received a Rockman warranty card in the mail from Jeff Beck.

While the Rockman is Scholz’s most celebrated invention, it was not his first. He previously designed an attenuator that he called the Power Soak. The first of its kind, it enables a guitar amp to operate at full volume to achieve that famously highly saturated and satisfying tone while allowing the output volume level to be set as quietly as desired, with minimal loss of tone quality.

But there is one creation Scholz has always kept to himself – his Hyperdrive pedal, which is essentially a heavily modified Echoplex analog delay unit. Aside from providing literally infinite sustain, it can produce all manner of otherworldly sounds. For example, check out the pick slide (and its after effects) at the 5:14 mark of the title track from Don’t Look Back (see below).

For a demo by the man himself, check out the YouTube video Tom Scholz: Sound Machine (see end).

Despite my appreciation for Scholz, I don’t own a Rockman. At first I was dismayed that I couldn’t use one to record this lesson’s musical examples. But then I thought it would be even more fun to get as close to Scholz’s signature tone as I could, using pedals I already owned. You very likely have similar pedals in your own collection, so use the following as a guide.

Scholz’s sound begins with an overdriven tone where the middle frequencies are boosted to be front and center. I reached for my Ibanez Tube Screamer pedal, which is well-known (or notorious, depending on how you see it) for this type of EQ structure.

Still, I felt I needed to boost the mids a bit more, as well as cut the surrounding low and high frequencies. I accomplished this with a Boss GE-7 seven-band EQ pedal.

Scholz’s sound is massively saturated, so I cranked the Tube Screamer’s drive knob all the way up. Yet, somehow, it didn’t have that oomph that I was looking for. I could have added another overdrive pedal here – a process known as gain-staging or gain-stacking – but it wasn’t so much that I needed a lot more overdrive; there was just something missing.

So instead, I reached for my Xotic EP booster and also made it “go to 11.” But note that I placed it before the Tube Screamer, causing the overdrive pedal to be “pushed” by the booster and creating more overdrive and adding a bit of color and fullness. It may not be the perfect Rockman tone, but it’ll do in a pinch.

For some finishing touches, I added spring reverb from a Fender Blues Jr., tape-style delay (from a DigiTech Echo Park), and compression (from a Bogner Harlow) for some warmth and sustain. (See above photo for pedal order and detailed settings. The guitar is plugged into the lower right side, the amp to the upper left.)

Lastly, Tom used Gibson Les Paul guitars almost exclusively on these first two Boston albums, so I’ve used mine here as well, on its bridge pickup.

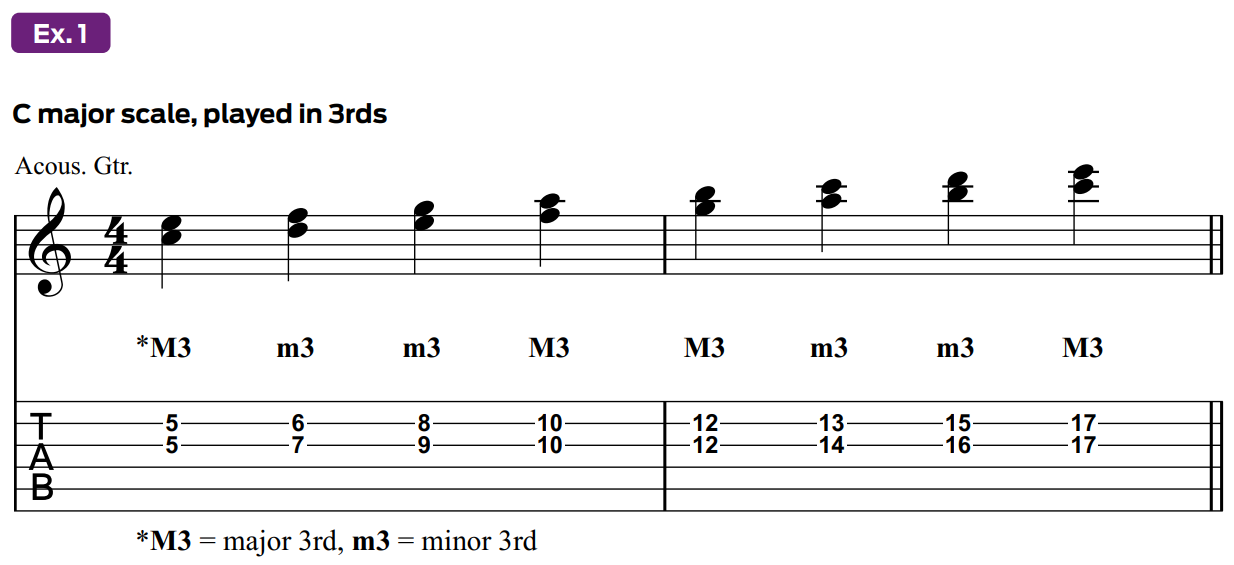

Now let’s create some lead harmonies. The most common musical intervals Scholz employed to create his harmonies – two or more notes played simultaneously – are the major and minor 3rd (two steps, and one and one half steps, respectively).

On the guitar, a major 3rd is the span of four frets on a given string, and a minor 3rd is three frets. So, for example, to create a major 3rd, you can play the note C on the G string’s 5th fret, followed by the E at the 9th fret.

To play and hear the notes simultaneously, move the E over to the B string’s 5th fret.

Ex. 1 shows the C major scale harmonized up the neck on the G and B strings in 3rds, as they occur diatonically, meaning within the scale. Note the pattern of major and minor 3rds, which is the same in every key.

Unfortunately, playing 3rds this way, on one guitar, with our heavily overdriven tone, will sound quite muddy, due to the interaction and interference among all the prominent harmonics.

The key to getting that crisp, clear Boston harmony-leads sound is to layer two independent single-note lines, each recorded on a separate track.

As an alternative, you can record the lower line and play the higher line along with it on playback, or vice versa. Separating the parts like this will eliminate the muddiness, allowing each guitar to “speak” clearly.

It’s interesting to note here that Scholz even recorded amplifier feedback in harmony.

If you’re not familiar with your major and minor scales, now would be a good time to brush up, so that you’ll be adept at visualizing intervals on the fretboard.

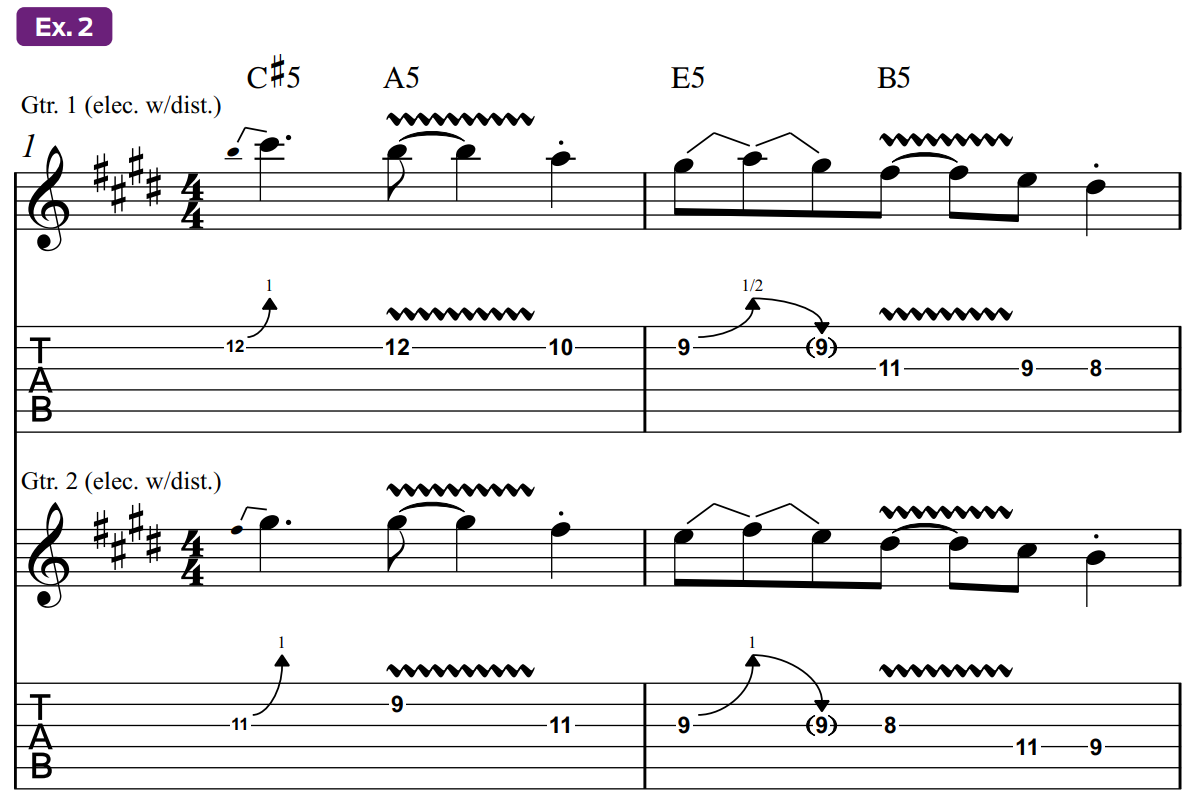

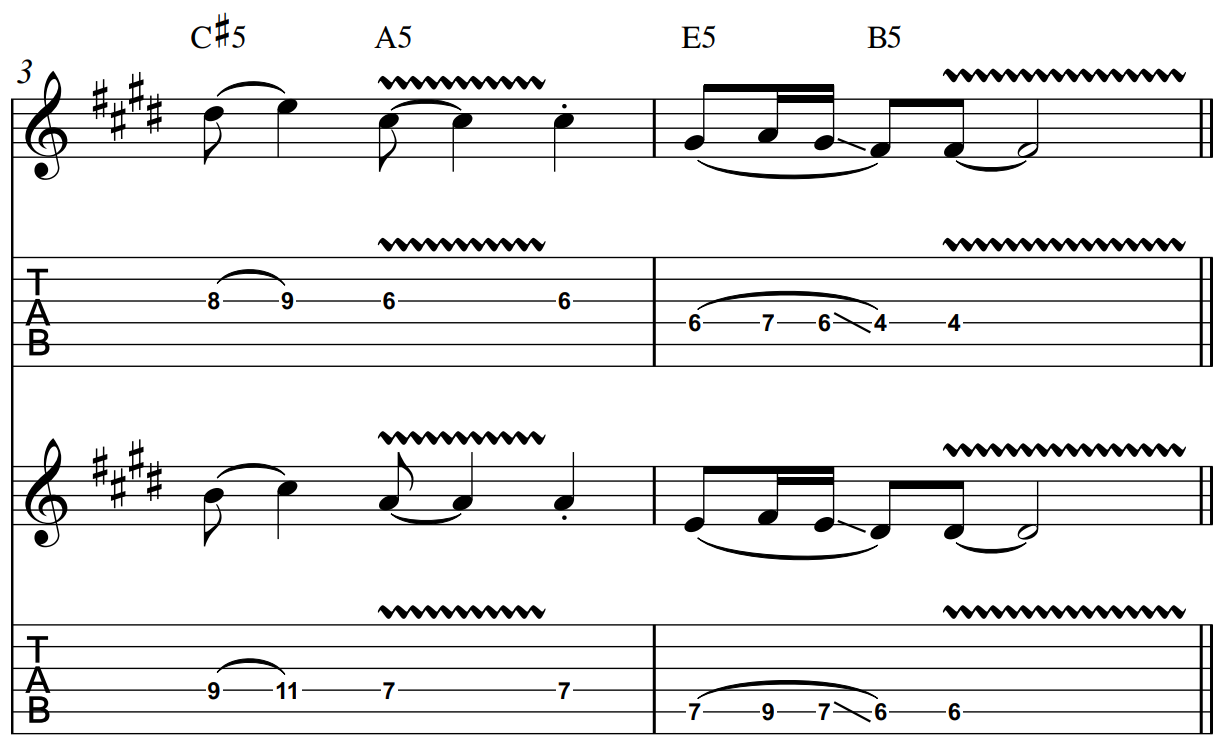

Inspired by Scholz’s composing and arranging in the classic track “Peace of Mind” (Boston), Ex. 2 emulates his approach to crafting ultra-melodic harmony-lead guitar hooks, here using notes from the C# natural minor scale (C#, D#, E, F#, G#, A, B), which is made up of the same seven notes as the E major scale (E, F#, G#, A, B, C#, D#).

Scholz’s playing style and touch also directly contribute to the unique quality of his melodies. Most noticeably, it’s his use of a smooth and distinctively wide finger vibrato, particularly used in combination with bent notes.

This bend vibrato technique, as it’s known, is a challenging skill that takes a bit of practice to refine. I’ve found the traditional rock-style fret-hand grip yields the best results. To perform it, hook your thumb over the top side of the fretboard, creating a fulcrum with the area between your thumb and index finger as it cradles the back of the neck.

Finally, the movement for both your bends and vibrato should come from turning your wrist, rather than pushing with your fingers, as this won’t provide as much strength and control.

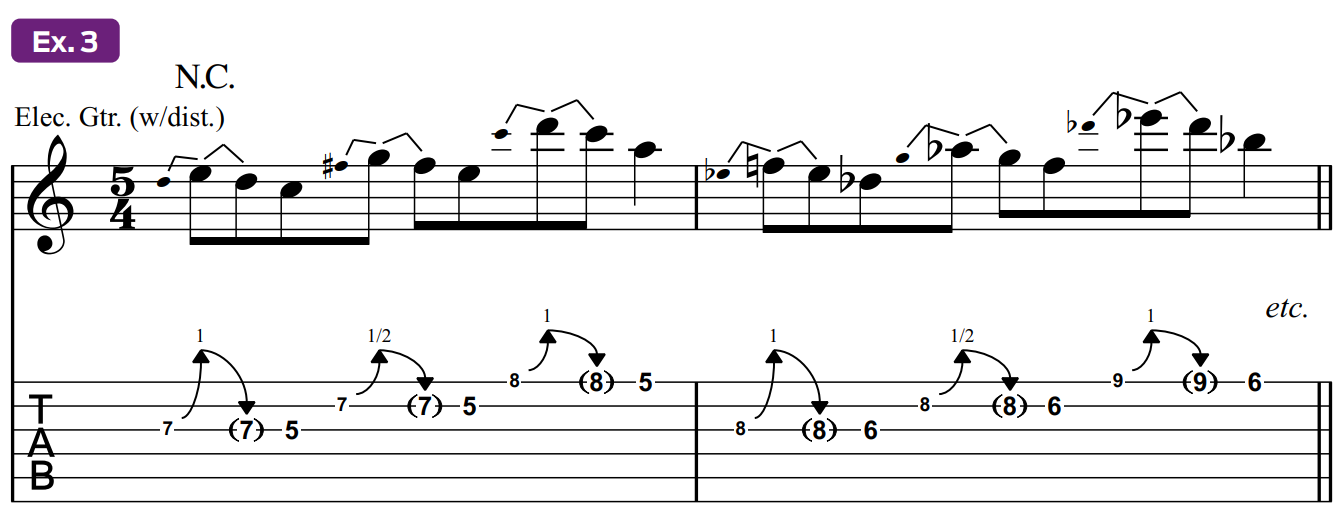

Ex. 3 offers a simple bending workout. First, focus on making sure your bends are in tune. The most accurate way to check a bent note’s intonation is with an electronic tuner. You can, of course, use your ears: Bend a note, say, up a whole step, which is the equivalent rise in pitch of two frets, then check it against the identical unbent note two frets higher on the same string.

However, using a tuner will simultaneously train your fret hand to feel precisely how far you’ll need to bend and your ears to recognize when each bend is spot on.

Also bear in mind that the amount of tension varies from string to string and in different positions. For example, bending down near the nut feels tighter than bending near the 12th fret, so you’ll need to adjust your touch in each case. Once your bends are consistently in tune, work on adding some vibrato.

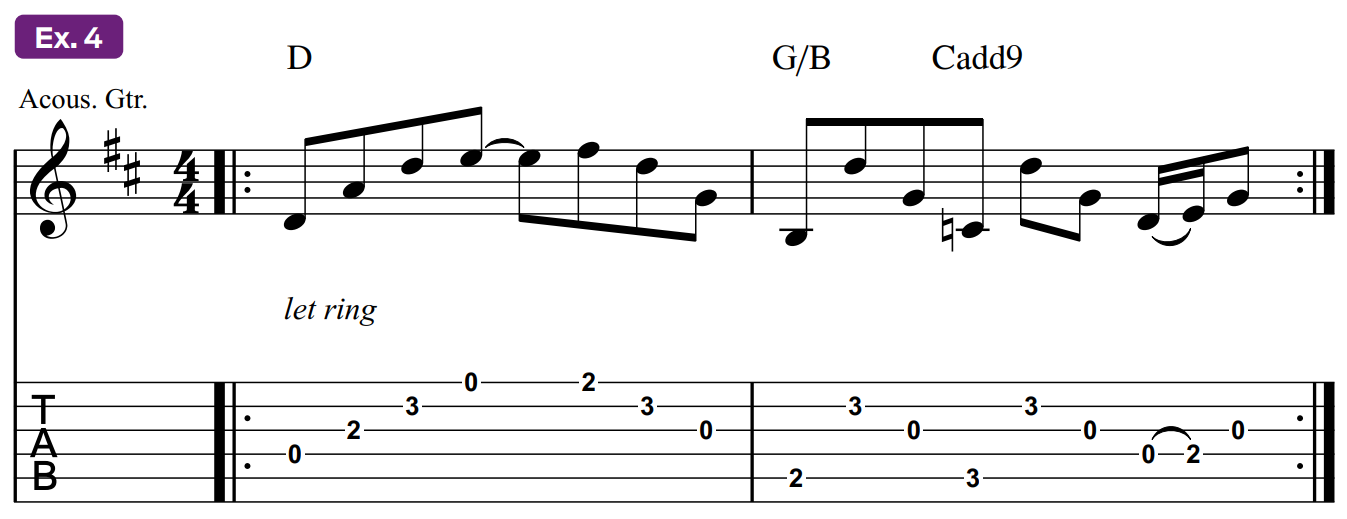

Next, let’s explore Scholz’s rhythm guitar style with some melodically arpeggiated chords inspired by another classic, “More Than a Feeling,” also from Boston (Ex. 4). This type of ringing figure is ideally suited for either acoustic guitar, or a clean-tone electric with a little chorus added.

Scholz would sometimes present a rhythm part on acoustic guitar, only to later duplicate it on overdriven electric, for tonal variety and excitement. For example, check out the 3:22 and 6:57 marks in “Foreplay/Long Time” from Boston.

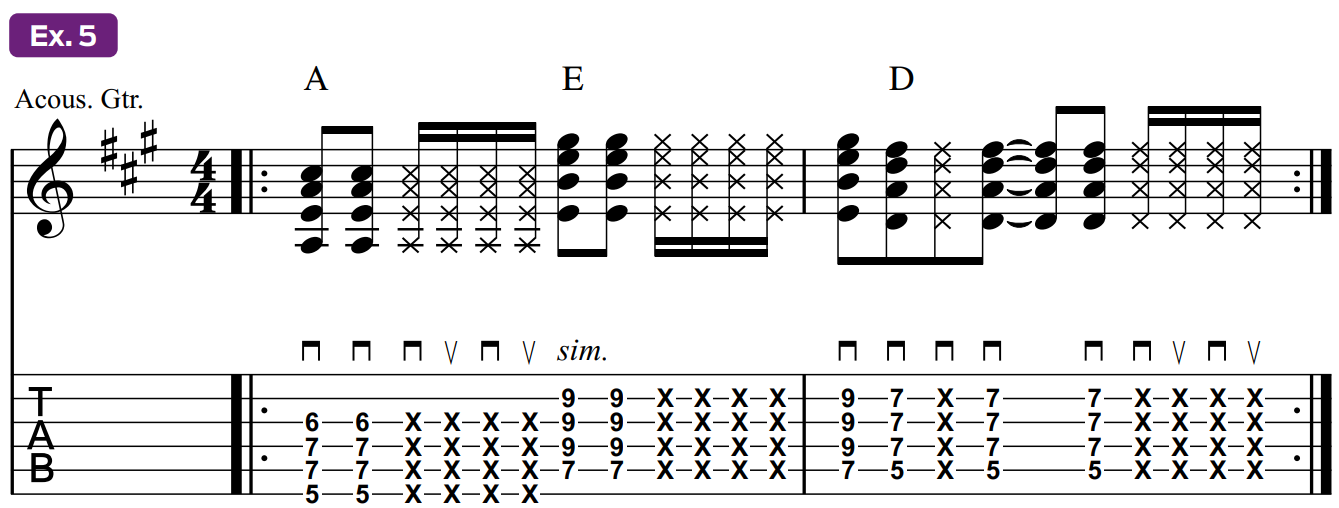

Ex. 5 is inspired by this classic opus. To perform the pitchless percussive strums (indicated by Xs in the notation), relax your fret hand’s grip on the chord shape, just enough so that the strings break contact with the frets, but without letting go of the strings. Then strum them. This is a key element of Scholz’s rhythm guitar style.

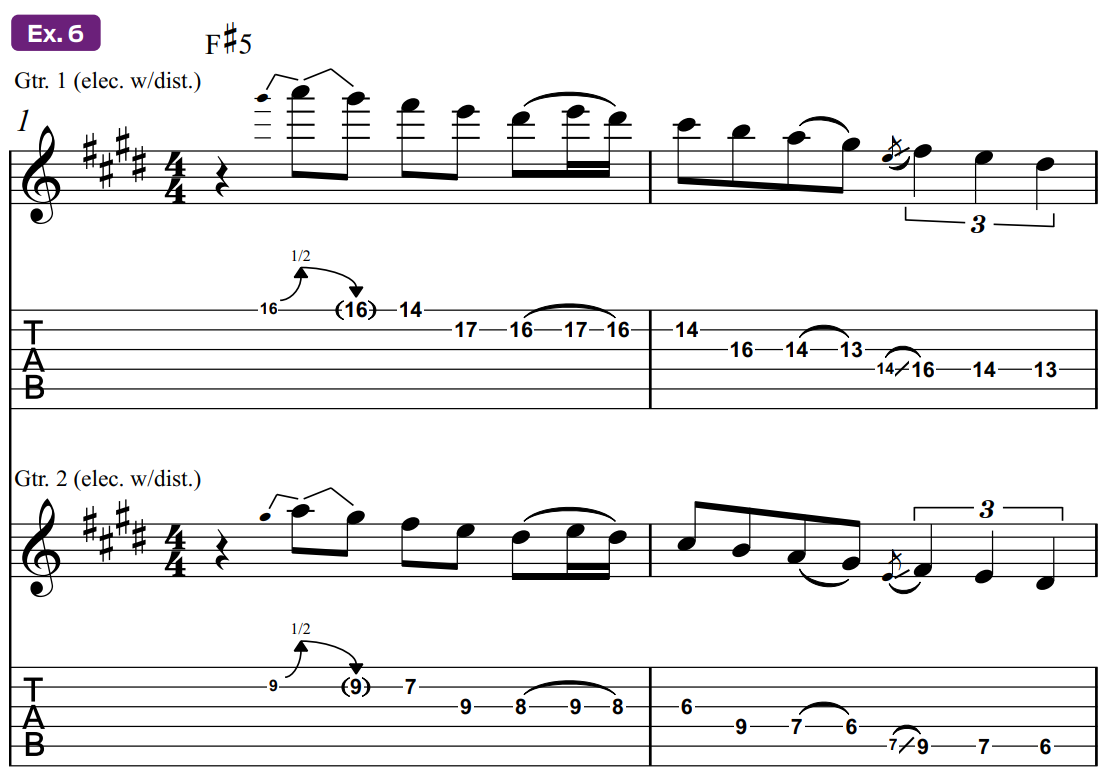

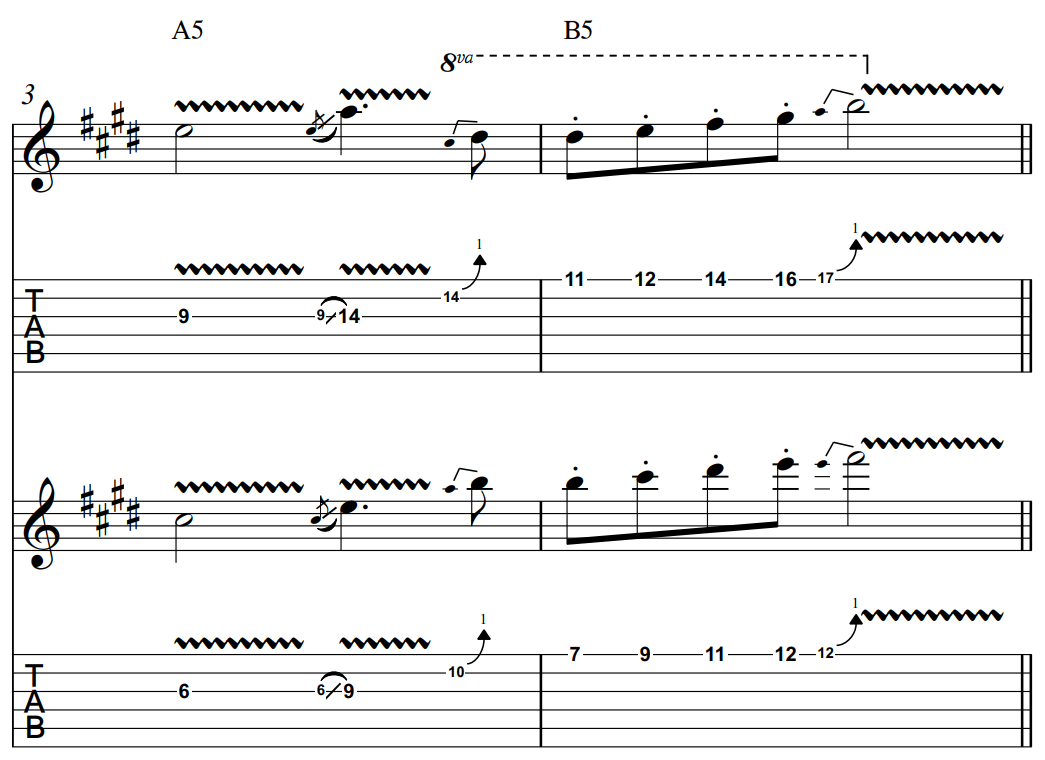

Scholz also employed his harmony guitar approach quite creatively in his solos. Inspired by his lead work in “Something About You” (Boston), Ex. 6 demonstrates how this arranging approach enabled the guitarist to achieve dramatic melodic crescendos.

Notice how the notes in the two parts are simply doubled an octave apart during the first two bars then switch to a climbing harmony of diatonic 3rds in bars 3 and 4, culminating with wailing, synchronized high bends and vibratos.

Since Don’t Look Back, Boston fans have had to wait roughly a decade between album releases, either due to legal battles or Scholz’s perfectionism.

The subsequent four records, from 1986’s Third Stage to 2013’s Life, Love and Hope, have seen Scholz pursue his twin-guitar harmony approach with less frequency, but his ability to write memorable guitar melodies endures, as does his signature Rockman sound.

Have a question or comment about this month’s lesson? Feel free to reach out to Jeff Jacobson on Twitter @jjmusicmentor or at jeffjacobson.net. Jeff offers private guitar and songwriting lessons virtually.

Jeff Jacobson is a guitarist, songwriter and veteran music transcriber, with hundreds of published credits. For information on virtual guitar and songwriting lessons or custom transcriptions, reach out to Jeff on Twitter @jeffjacobsonmusic or visit jeffjacobson.net.