“It’s the most amazing guitar. I’ve used it on nearly every single record.” Bill Wyman on the $15 bass guitar that powered the Rolling Stones’ classic hits — and became a priceless piece of rock and roll history

Long before stadium tours and Platinum sales, a cheap Dallas Tuxedo was the bassist’s secret studio weapon

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The Rolling Stones built their legend on hit records that earned millions. Yet the bass heard on nearly every album they cut with Bill Wyman began life as a flimsy, bargain-bin instrument he bought in 1961 for the equivalent of $15.

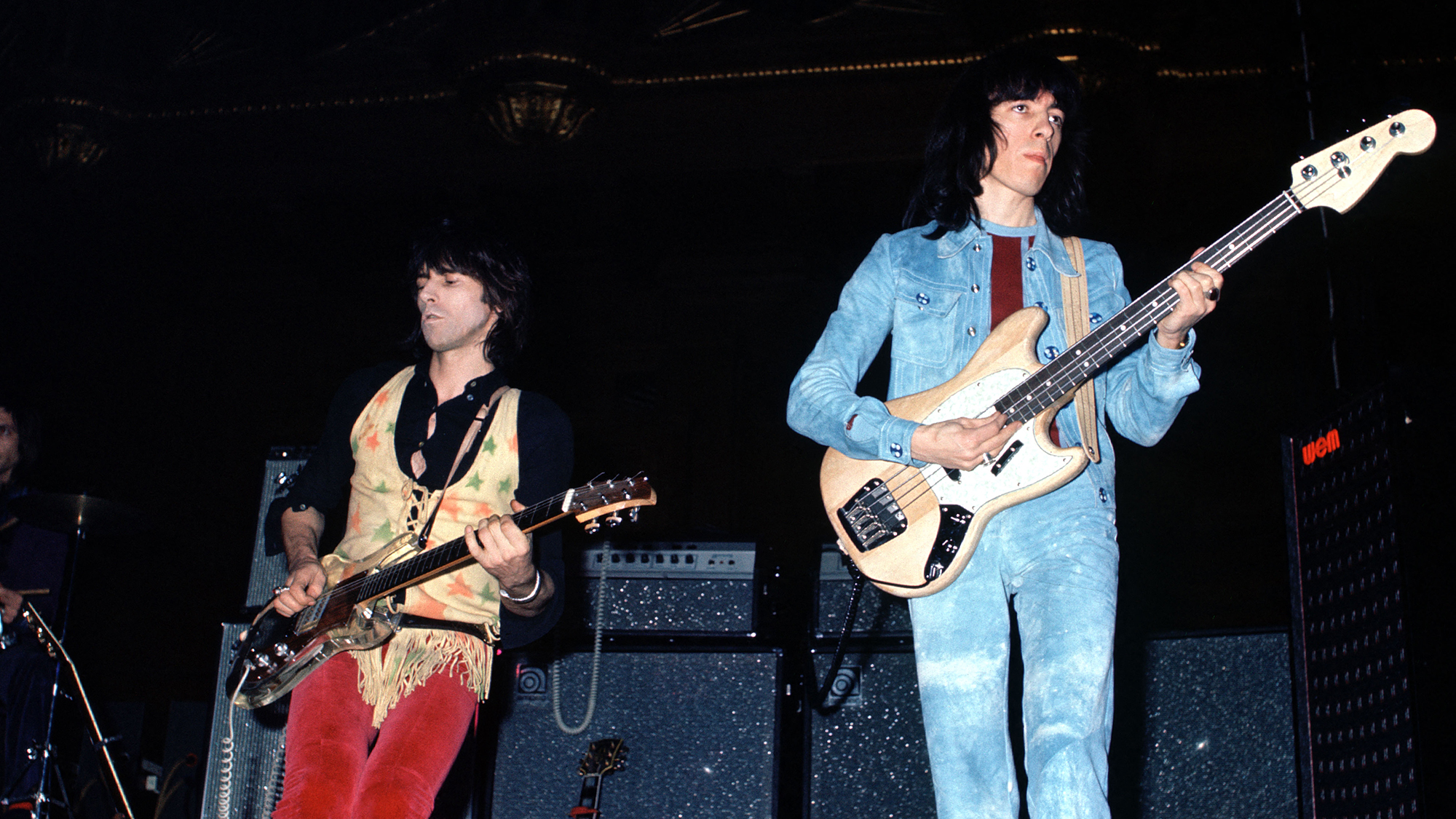

Wyman cycled through an array of basses during his tenure with the Rolling Stones, from December 1962 to January 1993. Fans saw him play Voxes, Gibsons and Fenders onstage.

But in the studio, he repeatedly reached for the same unlikely weapon: the cheap Dallas Tuxedo that cost him about a week’s pay.

Article continues belowIt was, in fact, his very first bass. Wyman had started as a guitarist, galvanized, like so many young U.K. players, by the acoustic-driven songs of skiffle king Lonnie Donegan.

“Lonnie Donegan was doing really well playing three-chord folk songs and old blues tunes. It seemed pretty simple,” Wyman told Guitar Player. “So I got a few guys together and we tried it.”

Their group, the Cliftons, played in London before the blues boom hit.

“I was playing guitar,” he says. “I wasn't interested in the bass until it became necessary for the band. I think a lot of bass players have started that way.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Lacking a proper bass, he simply tuned his guitar down seven frets at first. “It seemed like they couldn't go any lower without the strings getting too soggy to play,” he explained.

But hearing the full power of an electrified bass guitar was an epiphany. At a dance hall show by British pop outfit the Barron Knights, Wyman encountered the full force of an electrified bass for the first time.

“I remember walking from the stairway and through the door and being floored, just rooted to the spot, by this amazing sound,” he said. “It took me a moment to realize that it was the sound of the electric bass, and I was just thunderstruck by it.

“I thought, Well, I've got to get a bass, because this is where it's at. I could see the difference immediately.”

There was just one problem: money.

“When I went looking I found out that basses were something like 115 pounds,” he recalled. “I didn't have money like that. I was earning about eight pounds a week then and about to get married.”

It was a mess. The tuners were really bad, and the strings went straight over this solid piece of thing for a bridge. But it was a bass, and it was in my price range.”

— Bill Wyman

Salvation came via his drummer in the Cliftons, who tipped him off to a Dallas Tuxedo being sold for £8 — roughly $15 at the time.

“So we went and looked at it and, sure enough, it was a mess,” Wyman said. “It had a thin, flat body with one pickup. The body was big, but it had an incredibly thin neck. The tuners were really bad, and the strings went straight over this solid piece of thing for a bridge and through a hole and hooked on the back. It was also a horrible brown color.

“But it was a bass, and it was in my price range, so we scraped half of the money together and promised him the other half later.”

Before it was even paid off, Wyman began rebuilding it. One of the first bass guitars manufactured in England, the Tuxedo featured a Les Paul–style cutaway body and a short 30.5-inch scale. Combined with its slim neck, it suited Wyman’s small hands perfectly, but he decided to reshape the oversized body into something sleeker, with short horns inspired by Gibson designs.

There was like two or three extra inches around the edge, and I went down the road to my uncle's house and cut it out with his saw.”

— Bill Wyman

Armed with a cardboard template cut to the desired shape, he marked out the new curves on the body. “There was like two or three extra inches around the edge, and I went down the road to my uncle's house and cut it out with his saw.”

The glued-on frets were another liability — they buzzed badly — so he yanked them out and left them off. Though he’d never played fretless,“I figured I'd still have the lines in the fingerboard to go by if I took the frets out,” he said.

After sanding and refinishing the body, installing a Baldwin pickup and stringing it with Framus bass strings, he plugged into his “eight-watt Watkins” amp.

“It sounded fantastic,” he recalled.

Ironically, the modified Tuxedo wasn’t the bass he brought to his December 1962 audition for the Stones. At the time, he was playing a Vox Phantom through a Vox AC30 combo. Wyman later joked that the band was more impressed by the amplifier than the bassist.

“They thought, ‘Oh, really good amp; bass player's nothing special, but we'll keep him so we can use the amp.’ That was the general opinion, I have since learned. You know, they are real con artists, that lot.”

Within a month, though, he was back with the Dallas.

“It just had a sound that couldn't be beat.”

As the Stones’ fame escalated, the instrument became too valuable — and too vulnerable — for touring. “After a while I got really scared to take it on the road because I was afraid it would get stolen. That happened a lot in those days, with the kids pouring onstage and all that.”

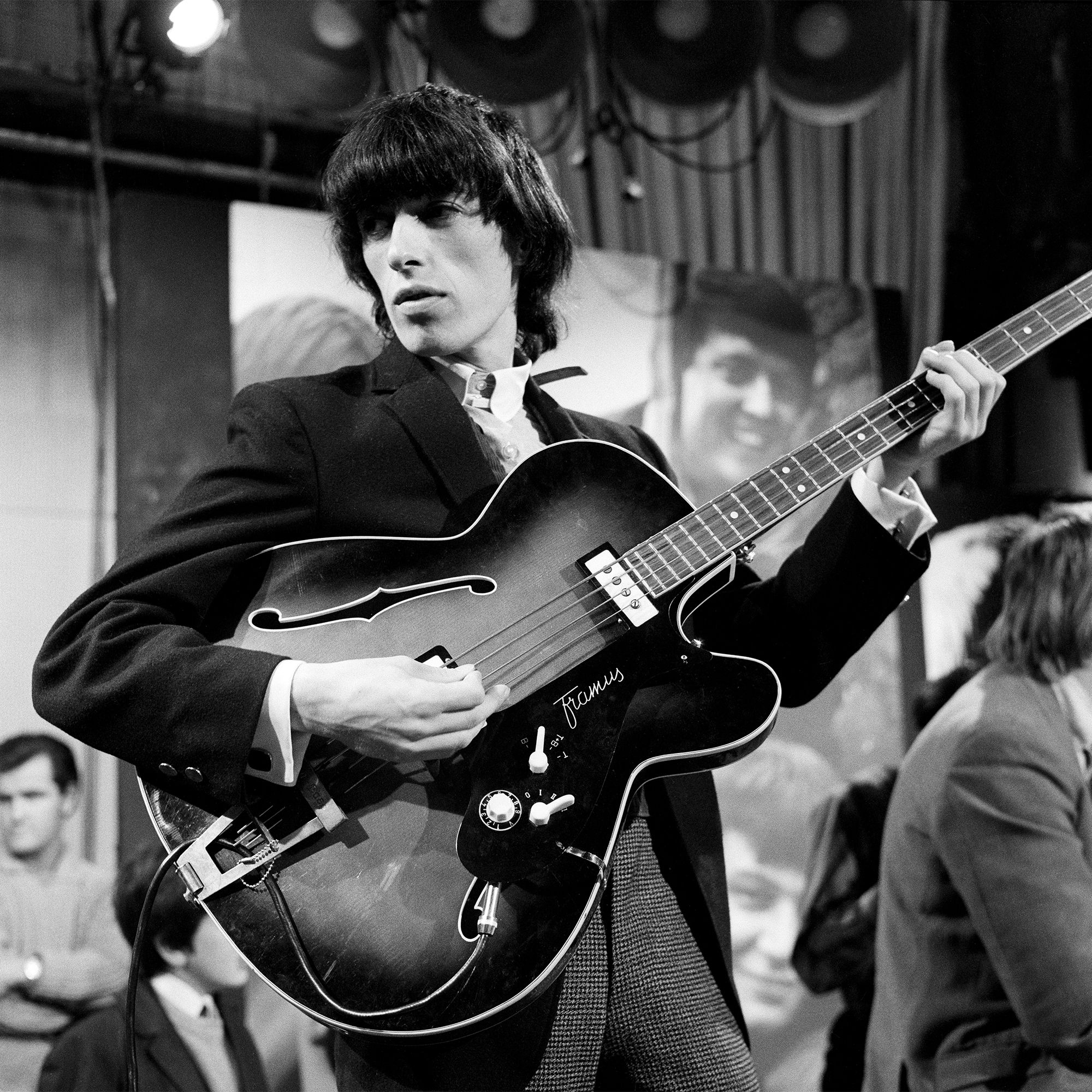

Though it occasionally surfaced on television — including at the Stone’ 1965 appearance on Top of the Pops where they mimed to their hit “The Last Time” — the Tuxedo largely retreated into the studio. There, it became Wyman’s secret weapon.

“I've used it on nearly every single record with the exception of the Some Girls album,” he told us in 1978. “I still use it even today for recording certain songs, because the sound is so pure and deep and rich.”

When pressed for specific examples, Wyman cited two tracks from 1971’s Sticky Fingers: “I Got the Blues” and “Sister Morphine.”

“‘I Got the Blues’ was probably one of the best songs I ever did with that one,” he said. “‘Sister Morphine,’ from the same LP, is another — a lot of the slow, bluesy things, the ballady things, songs where I wanted it to sound like a string bass. I can sort of slide on it because there are no frets, and I can almost get a little bit of that slap sound playing it with the thumb. I play every other bass with a pick, but I use my thumb on that one.

“It's the most amazing guitar. Everybody that tries it is flipped out.”

The $15 bass that underpinned a rock and roll empire sat behind glass at Wyman’s Sticky Fingers restaurant in central London until its closure in 2021. Wherever it is now, it remains a priceless piece of gear that helped shape one of the greatest — and most lucrative — music catalogs in rock history.

Christopher Scapelliti is editor-in-chief of GuitarPlayer.com and the former editor of Guitar Player, the world’s longest-running guitar magazine, founded in 1967. In his extensive career, he has authored in-depth interviews with such guitarists as Pete Townshend, Slash, Billy Corgan, Jack White, Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren, and audio professionals including Beatles engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott. He is the co-author of Guitar Aficionado: The Collections: The Most Famous, Rare, and Valuable Guitars in the World, a founding editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine, and a former editor with Guitar World, Guitar for the Practicing Musician and Maximum Guitar. Apart from guitars, he maintains a collection of more than 30 vintage analog synthesizers.