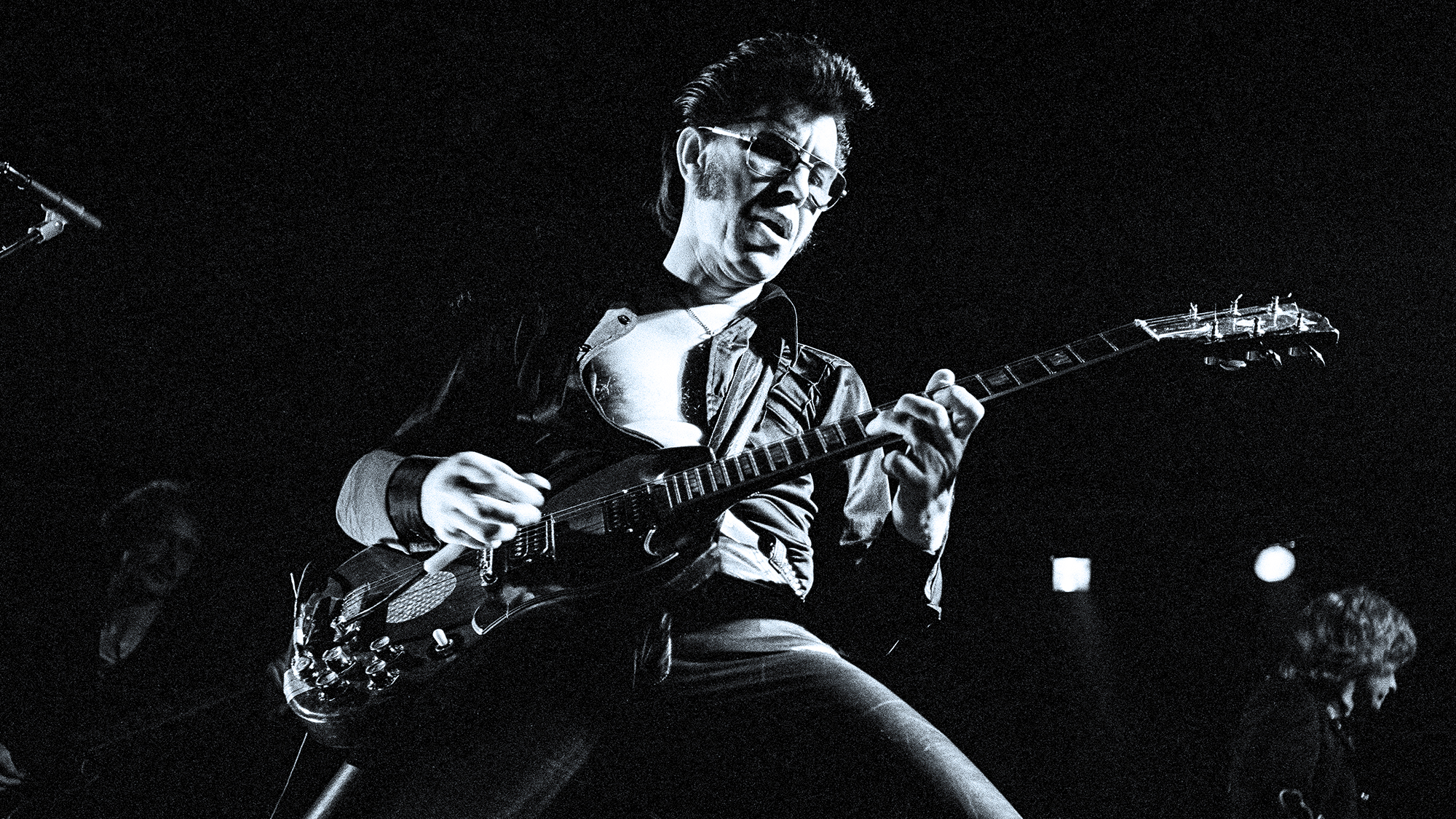

“We got the song in three takes, on one track, for 57 bucks. Isn’t God wonderful?” Guitar legend Link Wray on the hit that introduced distortion to rock and roll, inspired Jimmy Page to play guitar — and caused public outrage

Behind the 1958 guitar instrumental that changed rock and roll’s sonic landscape forever

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

When Link Wray recorded “Rumble” in early 1958, most rock-and-roll guitarists were doing everything they could to avoid distortion. Wray did the opposite, unabashedly leaning into it and, in the process, creating rock and roll’s seminal distorted-guitar instrumental. Unlike any song before it — and like few since — “Rumble” captured the raw essence of adolescence. It was the perfect soundtrack for a ballroom brawl or a backseat bump.

Wray’s ambitions for a singing career had nearly been derailed when he contracted tuberculosis. He spent a year in the hospital and had one lung removed. Though he eventually developed a distinctive, rough-edged vocal style, in the months that followed he focused on his guitar playing. It was during that period, one night at a sock hop, that he spontaneously wrote “Rumble.”

Wray’s use of distortion, his primitive energy, and his do-it-yourself ethic inspired countless guitarists. His legacy stretches from ’60s British rock — Dave Davies followed Wray’s DIY path to distortion on early Kinks hits — through ’70s punk and metal, into ’80s thrash and hardcore, and on to ’90s grunge. Along the way, distortion became available as a pedal effect, putting it within reach of every young rebel eager to follow in Wray’s footsteps.

When Guitar Player caught up with Wray for a November 1993 interview, he was 64 and living in Denmark with his 39-year-old wife, Olive Julie, and their 10-year-old son, Oliver. He had just released Indian Child, his first “commercial” effort in more than a decade. While the album had come out in the U.S., Rhino’s recent compilation Rumble! The Best of Link Wray provided the perfect excuse to have Wray revisit how his journey with distortion began in the 1950s.

“Back in the old days, the good guitars were too clean in sound,” Wray explained. “I was trying to find some off-brand guitar.” He recorded “Raw-Hide,” his second single, released in January 1959, with a Danelectro electric. “I ordered it out of a catalog for 60, 70 bucks. They sent me this longhorn guitar with mandolin pickups and more frets than a normal guitar. I ordered three or four of them.”

His love of distortion, it turned out, came from a simple need to be heard.

“When I was trying to get my music happening back in the ’40s, I was backing up all the cowboy stars like Lash LaRue, Wild Bill Elliott, and Sunset Carson. I played through these Sears and Roebuck amplifiers. They would burn up on me because I wanted to turn them up to 10.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

My brother said, ‘You’re crazy, Link.’ I said, ‘I’m not crazy. I just want to hear myself.’”

— Link Wray

”I bought four of them and hooked them all together. My brother said, ‘You’re crazy, Link.’ I said, ‘I’m not crazy. I just want to hear myself.’”

Wray’s brother Vernon was a recording artist himself, scoring a hit with “Remember You’re Mine,” released on the Cameo-Parkway label. The song was written by Cal Mann, who also penned Elvis Presley’s “Teddy Bear.”

“Bernie Lowe, who owned Cameo-Parkway, wanted Vernon to change his name,” Link recalled. “He said, ‘What are you going to change it to?’ Bernie said, ‘Instead of Vernon Wray, let’s call you Ray Vernon.’ So he changed it backwards. Ray wrote a song on the flip side called ‘Evil Angel.’”

As Wray tells it, “Remember You’re Mine” never stood a chance. Pat Boone, the clean-cut version of Elvis Presley, covered it three days after its release and took it to number one.

“He was covering everybody in those days. It killed my brother as an artist.

“Later on, God gave me ‘Rumble.’ I said, ‘Ray, let’s see Pat Boone cover this motherfucker!’”

That gift, Wray said, arrived at a teen dance party where Link Wray & His Wray Men were on the bill.

“I was playing record hops with Milt Grant in Fredericksburg, Virginia. He was the big disc jockey there — like a Dick Clark, but local to the Washington, D.C., and Maryland area.

God gave me ‘Rumble.’ I said, ‘Let’s see Pat Boone cover this motherfucker!’”

— Link Wray

“Milt says [in a low voice], ‘Link, play “The Stroll.”’”

“The Stroll,” a 1957 hit by the Diamonds, was accompanied by a slow line dance of the same name.

“The Diamonds, who had the number-one hit, were going to dance the Stroll while I tried to play jive,” Wray said. “I told him, ‘I don’t know the fuckin’ Stroll!’ My brother Doug said, ‘I know the Stroll beat. Just start playing something on the guitar.’

“So God zapped it. I just started playing it.”

The sound that night, Wray recalled, was cataclysmic.

“Ray had stuck the microphone in front of the amplifier, and it was just pouncing all over the place. The kids were going wild. Nobody put microphones in front of amplifiers in those days.”

Built from just three power chords, the improvised tune was such a hit that the crowd reportedly demanded it be played four times that night. Grant financed a studio recording on the condition that he receive a songwriting credit alongside Wray.

But once in the studio, Wray couldn’t recreate the sound he’d unleashed in Fredericksburg — which led to one of rock’s most infamous acts of sabotage.

Ray said, ‘You’re just screwing up your amplifier.’ I said, ‘Who cares as long as we get a fuckin’ sound, man!’”

— Link Wray

“When we went to record ‘Rumble,’ I didn’t get that live sound. It was too clean. In Fredericksburg, those Sears and Roebuck amplifiers were jumping up and down, burning up with sound.

“Ray said, ‘What are we going to do about it?’ I said, ‘I’m going to fuck with the amplifier like it was fucking up at the live gig.’”

Armed with a pen, Wray punched holes in the tweeters of his Premier amplifier.

“Ray said, ‘You’re just screwing up your amplifier.’ I said, ‘Who cares as long as we get a fuckin’ sound, man!’”

His gamble paid off.

“I started playing and got that distorted sound, plus the tremolo — ‘chik, chik, chik, chik.’ We got the song in three takes, on one track, for 57 bucks.” Wray laughed. “Isn’t that amazing? Isn’t God wonderful?”

“Rumble” went on to light the way for generations of guitarists, including Jimmy Page. “The first time I heard ‘The Rumble,’” Page said in the 2008 documentary It Might Get Loud, “it had such profound attitude.” Pete Townshend wrote in the liner notes for 1974’s The Link Wray Rumble that the song inspired him to play guitar. Bob Dylan was so taken with it that he opened four shows during his 2005 Brixton Academy residency with “Rumble,” calling it the greatest instrumental of all time.

I recorded it three months after I had my lung taken out. It was a four-million seller. So yeah, I think God loves rock and roll.”

— Link Wray

The song’s sense of menace nearly kept it from being released at all. Archie Bleyer, owner of Cadence Records, hated it and initially refused to put it out until his teenage stepdaughter convinced him otherwise. Phil Everly of the Everly Brothers, a Cadence act at the time, suggested calling it “Rumble,” since the sound reminded him of a street-gang fight.

Between its music and name, “Rumble” proved too dangerous for some radio stations, which banned it, keeping the song from climbing higher than number 11 on the charts.

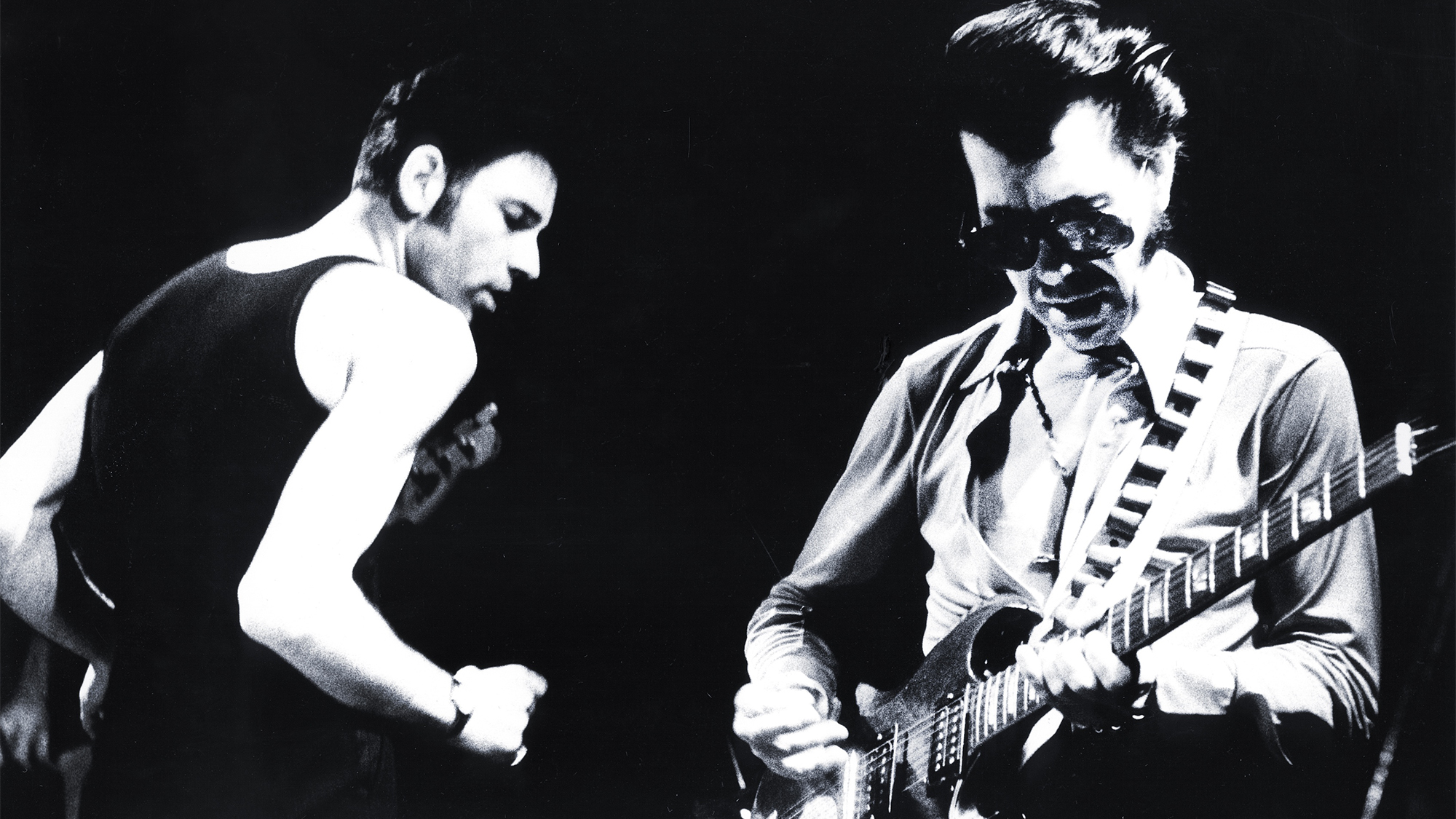

Even so, Wray — who would go on to perform with rockabilly revivalist Robert Gordon in the 1970s — built an entire career around it, rerecording “Rumble” in the 1960s and collecting royalties from covers by everyone from surf-rockers the Trashmen to jazz guitarist Bill Frisell.

Wray gave all credit to God.

“My 10-year-old son says, ‘Daddy, you’re very spiritual.’ He asked me, ‘Daddy, does God love rock and roll?’ You know, because some churches say rock and roll is evil.

“I said, ‘Well, honey, he pulled me out of the death house and gave me “Rumble.” I recorded it three months after I had my lung taken out. It was a four-million seller.’ So I said, ‘Yeah — I think God loves rock and roll.’”

- Christopher ScapellitiGuitarPlayer.com editor-in-chief

![Link Wray - Rumble [HQ - Best Version] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/ucTg6rZJCu4/maxresdefault.jpg)