“We had to tell her that the console had quit. They didn't like that at all.” Never mind Keith Richards and the Rolling Stones. Here's how Grady Martin, Nancy Sinatra and Ann-Margret helped the fuzz pedal become every guitarist's favorite effect

Between the effect's creation and its development as a guitar pedal, interest was kept alive by a trio of fuzz-loving musicians

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The story behind the fuzz pedal’s creation is well known to most guitarists, but it goes a little something like this. The effect was born on July 12, 1960, while country superstar Marty Robbins was cutting the song “Don’t Worry” at Bradley Film & Recording Studios in Nashville, better known as the Quonset Hut. Hired for the session was guitarist Grady Martin, who brought along his Danelectro UB-2 six-string bass guitar.

Studio house engineer Glenn Snoddy was running the board, a newly installed custom-built recording console featuring Langevin 116 tube amplifiers. Martin’s guitar, used for the song’s solo, was being sent directly into the console, rather than through an amp.

To everyone’s surprise, when Snoddy played back the take, Martin’s six-string bass sounded like a swarm of bees.

In a 2014 interview with the National Association of Music Merchants (NAMM)’s Oral History Program, Snoddy put the problem down to one of the board’s 35 output transformers.

“Prior to making the transformers, they misjudged the windings somehow or other, and there were 250 volts going through the winding instead of the transformers,” he said. “And one malfunctioned at the exact time that Grady was playing his guitar solo through it and it caused this sound, which we called later a fuzz tone sound.”

According to Snoddy, it was Martin who suggested they keep it.

“Grady said, ‘Why don’t we just use that on this record?’” the engineer recalled in the 2010 book How Does It Sound Now? Legendary Engineers and Vintage Gear.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Martin’s advice was well taken. Released in February 1961, some six months after it was recorded, “Don’t Worry” became Robbins’ seventh number one on the country chart, and crossed over to the pop chart, where it peaked at number three.

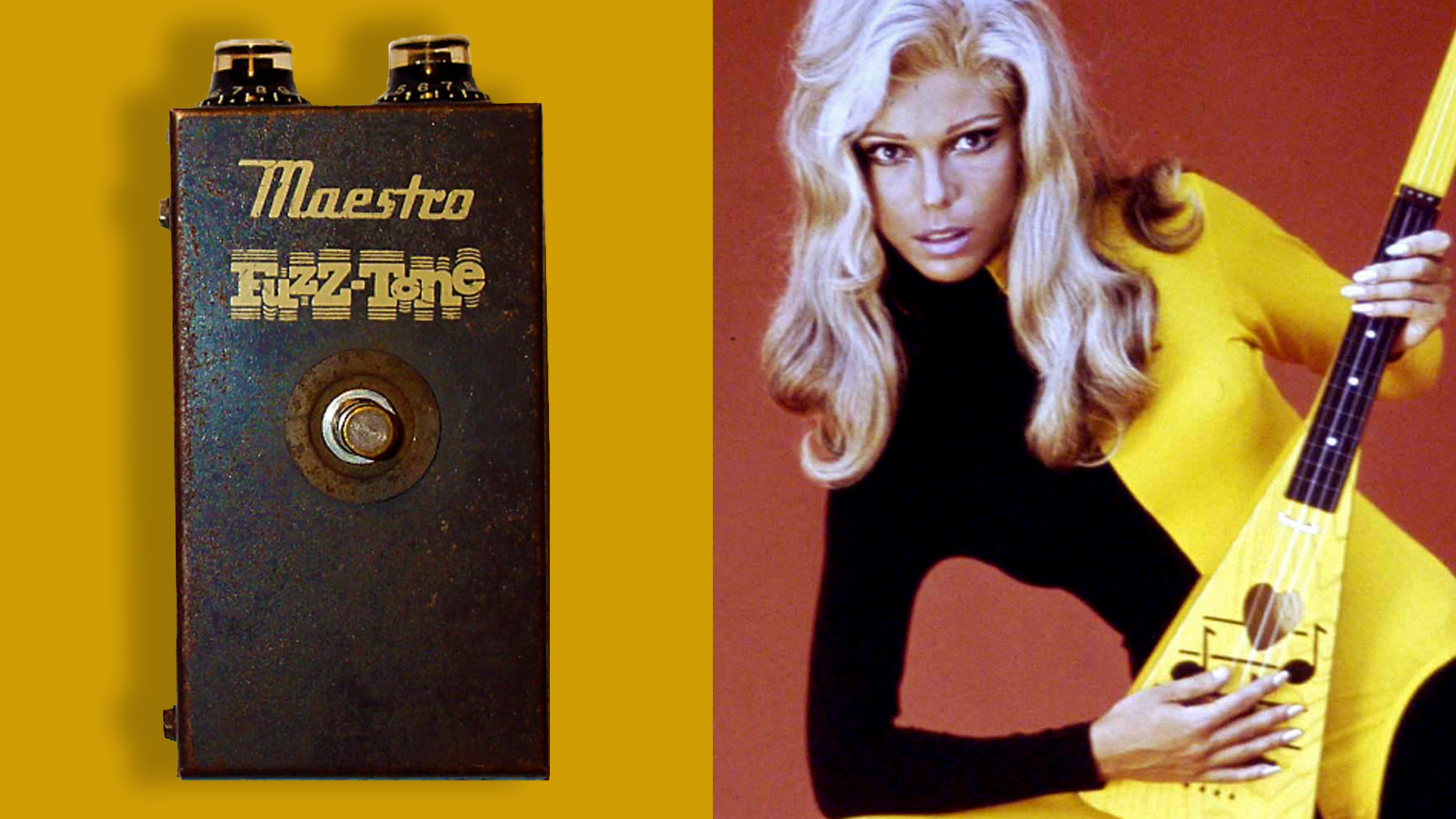

But before that happened, Snoddy’s fuzz circuit had died, taking with it that magic sound. By then, artists were calling the Quonset Hut to ask if they could get the fuzz tone on their recordings. Snoddy decided to replicate the circuit in a pedal format with an old friend, engineer Revis Hobbs. Together the pair set to work on a circuit design using transistors, and re-created the fuzz sound by clipping the signal’s sine wave to a square wave.

“I got some transistors, and we rigged up a thing, and we eventually sold it to Gibson,” he recalled

Gibson introduced the Maestro FZ-1 Fuzz-Tone the following year, in 1962. Although the pedal initially met with a muted public response, it finally took off in 1965 after Keith Richards used an FZ-1 to record his lead riff on the Rolling Stones hit “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction.” Ever since, fuzz has been an essential part of the electric guitar tone arsenal.

I got some transistors, and we rigged up a thing, and we eventually sold it to Gibson."

— Glenn Snoddy

But between Snoddy’s circuit failing and the birth of the FZ-1 are at least three recording artists who helped maintain interest in the effect, all of which helped launch it to its rightful place as an essential pedal in guitarists’ rigs.

The first is the man behind the six-string bass guitar on that transformational session: Grady Martin. As an established Nashville player, Martin knew a thing about making hit records. By 1961, he’d already enjoyed a long career as one of country music’s most in-demand guitarists and become a member of the Nashville A-Team, who, like their counterparts in L.A., the Wrecking Crew, would define the sound of numerous records, including Marty Robbins’ 1959 hit “El Paso.”

Martin liked the sound of Snoddy’s failing circuit so much that he made at least two other fuzz-guitar songs with it. “Tippin’ In” and “The Fuzz,” both instrumentals, were recorded on January 12, 1961 and issued together as a single that same month — before the February release of “Don’t Worry.” Neither was a hit for Martin, but “The Fuzz” likely sealed the deal when it came to the effect’s name.

Martin’s adoption of the fuzz effect didn’t go unnoticed by Snoddy, who appreciated the guitarist’s keen ear for sound. Unfortunately, the circuit was dead by the time those sides were out and “Don’t Worry” was climbing the charts.

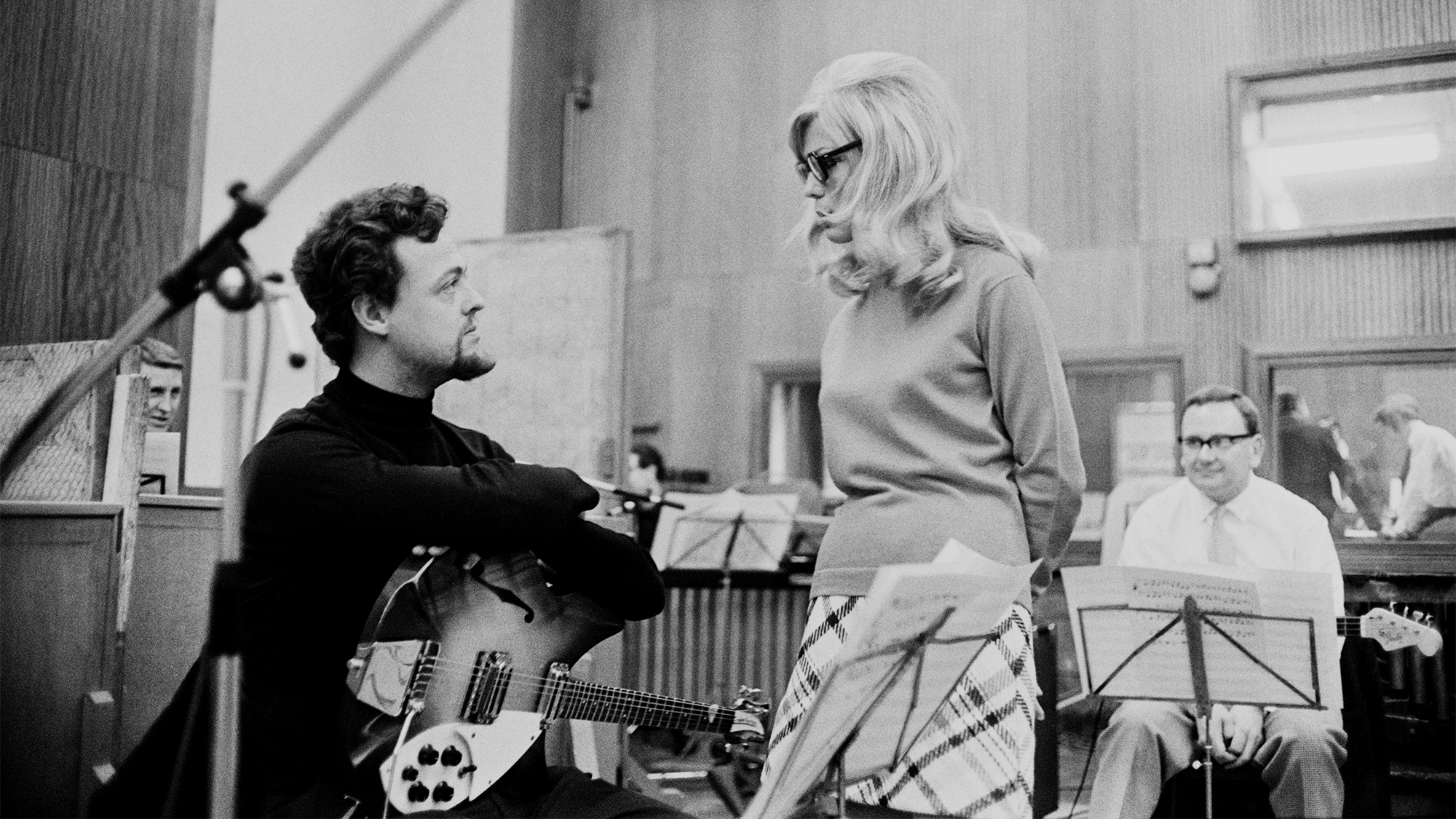

What pushed Snoddy to re-create the effect in a pedal? He said the final straw was when Bradley had to turn away Nancy Sinatra when she came looking to use the sound on her next record.

"We had an artist, Nancy Sinatra, that called and wanted to come in and make a record,” the engineer explained. “When she got there, we had to tell her that the console that was causing that sound, the amplifier, had quit, and we couldn't do it anymore.

“They didn't like that at all,” he said with a laugh. “I told [Quonset Hut owner and producer] Harold Bradley that I'd have to see if I could make one and get it going."

So is Nancy Sinatra the mother of the fuzz pedal? It’s a little hard to imagine the young singer was interested in Snoddy’s fuzz sound. Consider that, in 1961, Sinatra was just launching her career as a teenybopper singer of saccharine love songs that often featured orchestrations, not fuzzed-out guitars. Her confidently sassy breakthrough success “These Boots Are Made for Walkin’” was still four years away.

What's more, Sinatra was recording for her father’s new label, Reprise, located in Los Angeles. Frank Sinatra had recorded his own early Reprise sides in L.A., at United Recorders. Why would Nancy look to record in Nashville? And would a raunchy guitar sound really be in keeping with the sweet-girl image she was cultivating in 1961?

Whatever the case, let's take Snoddy at his word; Sinatra, after all, would have had license to record wherever she damn well pleased. But note that she didn’t cut a song with fuzz guitar until her 1967 hit, “You Only Live Twice,” the theme from the James Bond film of the same name.

But another dusky-voiced young singer getting a start on her career did use the fuzz effect on a single in 1961. What’s more, she did it in Nashville, just a few months after “Don’t Worry” ‘came out.

Ann-Margret was just 20 years old and on her way to a successful career as a vocalist and movie actress when she released her first single for RCA Victor, the heartfelt “Lost Love,” early that year. Soon after, she followed it up with the very fuzzy — and more adult — “I Just Don’t Understand.”

Recorded at RCA Victor Studio B, Nashville on May 9, 1961, and produced by Chet Atkins, “I Just Don’t Understand” features Billy Strange on electric fuzz guitar. Strange, who would go on to record for the Beach Boys as part of the Wrecking Crew, reportedly had his guitar tone altered by overdriving the input preamp on a channel of the recording console. (He would even go on to record his own version of the Stones’ “Satisfaction.”)

“I Just Don't Understand" was a hit for Ann-Margret, reaching 17 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart in 1961 and furthering fuzz guitar’s insinuation into the American psyche.

To be clear, there’s little chance Snoddy misremembered Ann-Margret as Nancy Sinatra. As an RCA Victor artist, she was unlikely to record in a rival studio like the Quonset Hut, which catered largely to artists on Decca, MGM and Columbia, the latter of which bought the studio from Bradley in 1962.

But Ann-Margret’s chart success says something about the popularity of fuzz in 1961, before the development of the Fuzz-Tone. Had Snoddy not put the sound in a box, chances are someone else would have.

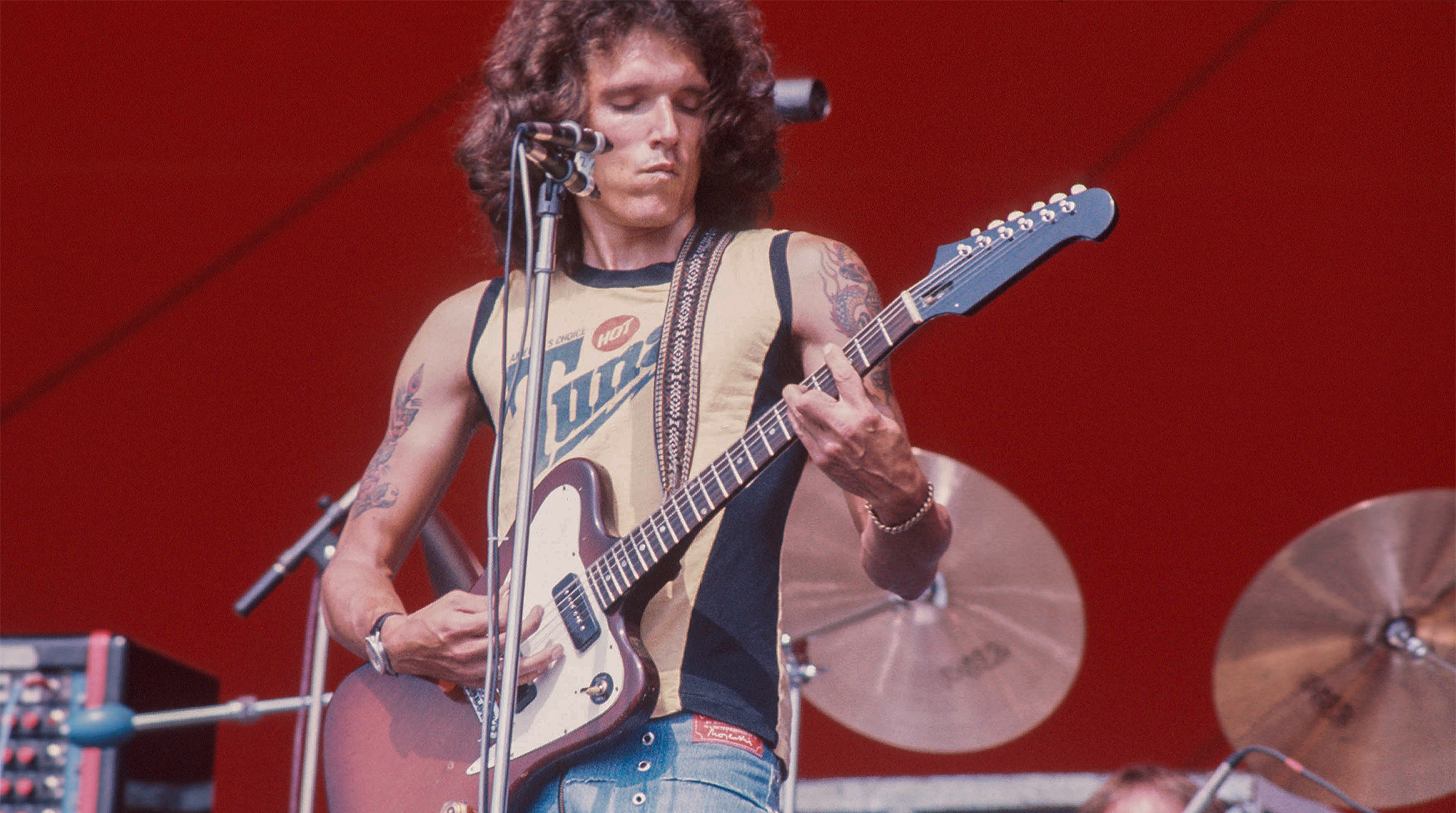

As for Grady Martin, he continued to use the fuzz effect well after Snoddy’s circuit kicked the bucket, creating a quartet of sides that slot neatly into the garage-rock genre.

In February 1962, Martin used fuzz on both sides of his single “Twist and Turn”/“Good Good Good,” released in April 1962. He employed it as well on two other songs cut at this session: “Ramblin’ Rose” and “Big Bad Guitar,” both included on the 1963 album That Good Grady, cut with the Slewfoot Five.

Two years later, those same two recordings would be reissued with vocal overdubs and credited to Beauregard and the Tuffs. No doubt it was this raucous cut of “Ramblin’ Rose” that inspired the MC5’s version from their 1969 album, Kick Out the Jams, which in turned launched a new wave of garage rock that gave birth to punk.

Given that Snoddy’s circuit was long gone by the time Grady cut those sides, it’s anybody’s guess how he achieved his fuzz effect. But it wouldn’t be a surprise if he used the FZ-1.

Christopher Scapelliti is editor-in-chief of GuitarPlayer.com and the former editor of Guitar Player, the world’s longest-running guitar magazine, founded in 1967. In his extensive career, he has authored in-depth interviews with such guitarists as Pete Townshend, Slash, Billy Corgan, Jack White, Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren, and audio professionals including Beatles engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott. He is the co-author of Guitar Aficionado: The Collections: The Most Famous, Rare, and Valuable Guitars in the World, a founding editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine, and a former editor with Guitar World, Guitar for the Practicing Musician and Maximum Guitar. Apart from guitars, he maintains a collection of more than 30 vintage analog synthesizers.