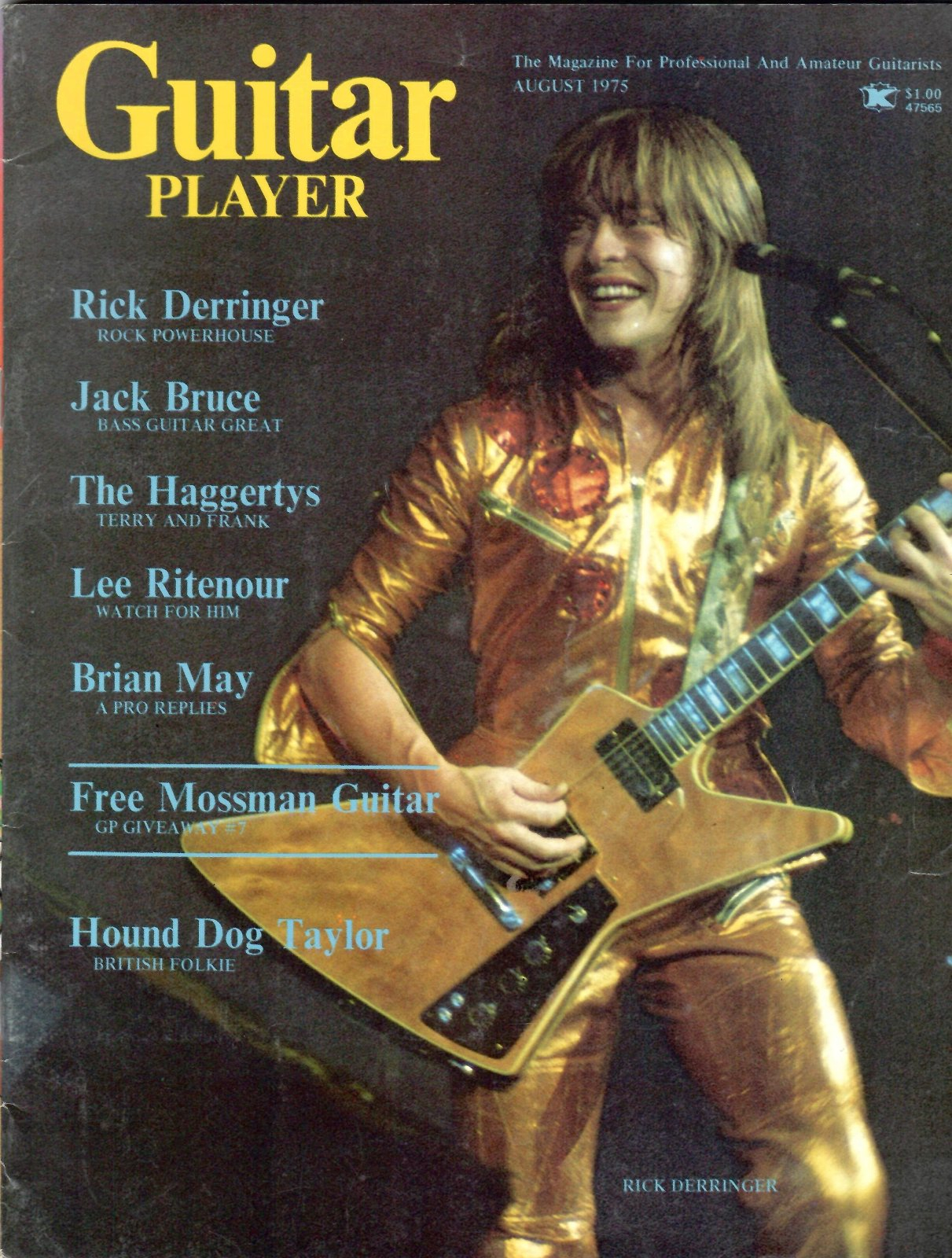

“If You Want to Play Guitar, It Isn’t Something That Comes Overnight”: A 27-Year-Old Rick Derringer Details His Gear, Technique and Outlook in This Savvy Interview From the ‘GP’ Vault

“My personal goal is just to make the next thirty years, or the next fifty,” Rick Derringer told ‘Guitar Player’ in 1975

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Little nine-year-old Rick Zehringer, with wide lapels, slicked-back hair, and a bow tie, staring out of some mirror of the past facing his own future, would have been hard put to recognize the form he’s taken today as Rick Derringer – rock guitarist, songwriter, and producer for himself as well as for such luminaries as Johnny and Edgar Winter, the Osmond Brothers, Richie Havens, Steely Dan, Todd Rundgren, and even Alice Cooper. Squinting wouldn’t help young Zehringer recognize his new form. Little in his life is the same.

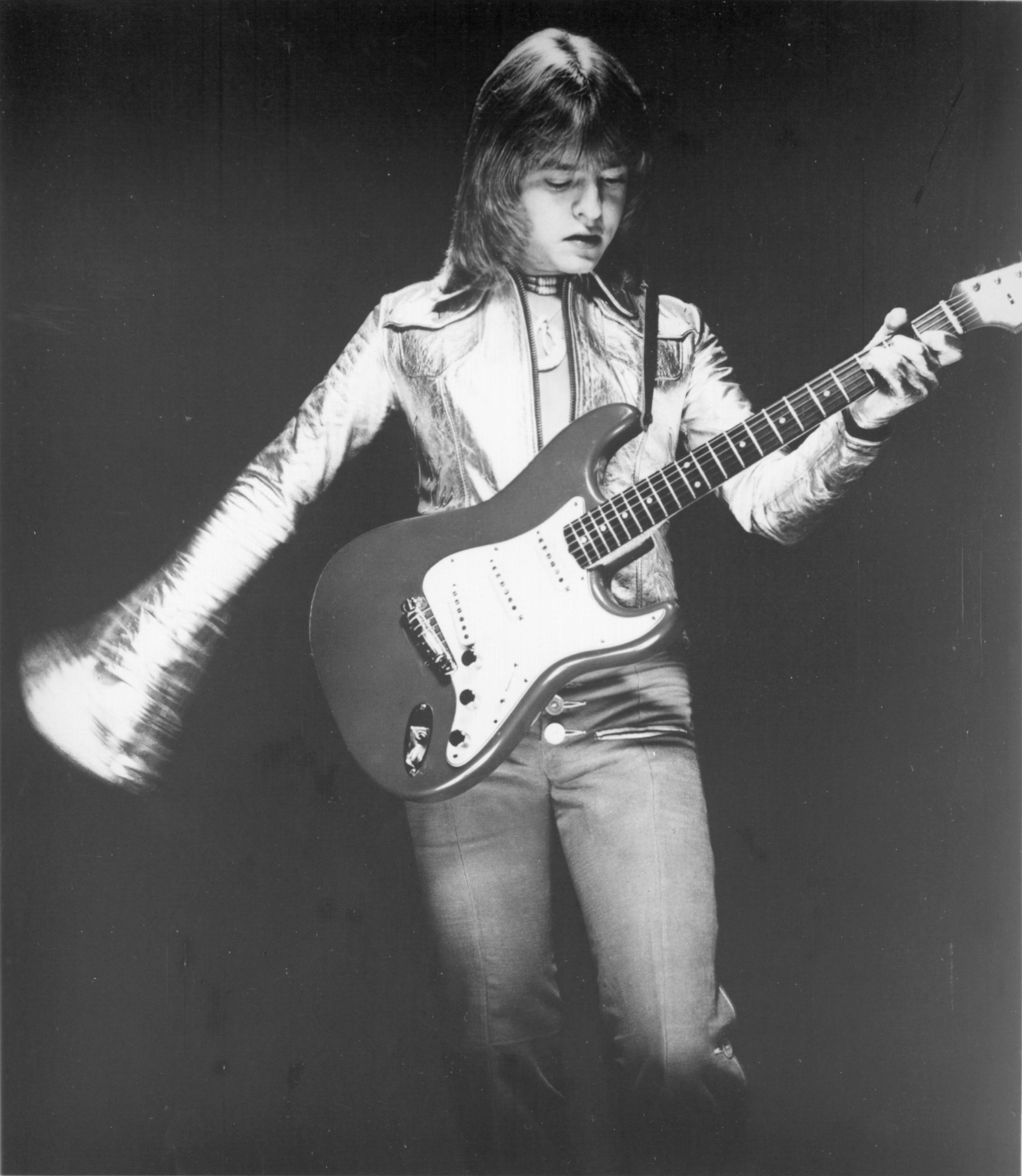

His audiences, for example. Rick, at nine, was strumming country-western ditties for the dozing town fathers of Fort Recovery, Ohio at their Kiwanis and Rotary Club luncheons. Today, nearly two decades later (he’s pushing 28 now), Derringer’s electrifying the whole world’s sons and daughters that storm the stages of rock and roll halls everywhere he goes.

Instruments, too, have come and gone. He’s owned everything from a three-pickup white Supro (“Now, that was a hot looking guitar!”) to a rare Explorer, which is the visual counterpart of the custom instrument he now uses on stage.

Today Derringer can hardly recall the titles from his parents’ large record collection, which he describes as “a lot of country-western records, just a lot of Fifties kind of music, not too much rock,” though the name Spike Jones sticks in his head. “Find all those old records,” he says, “and re-release them, and he’d probably be bigger than Frank Zappa. He’s funnier, more innocent.”

His influences have changed, as well. His first was an uncle in Michigan who played in bars - “a real vague kind of music, more in a real musical way than people learn how to play nowadays.” Rick’s musical drive was encouraged by his parents, who were willing to take him into bars to listen to the local guitarists. Today, though his primary interest is rock and roll, he tries to catch as many different kinds of acts as possible, including jazz, when it’s possible for him to track down such performers.

Perhaps this avidness is Rick’s most noticeably consistent quality. He’s always learned from everyone he could. “Every time I’d meet a guitar player,” he recalls, “I’d get him to show me something.” He took lessons from piano teachers, learned to read music (“not fantastically, but enough to get by”), and began buying records, more Top 40 than rhythm and blues (that came in later), since Top 40 was all that was on the radio. “And that, in the Midwest,” Derringer explains, “was a real mixture of Jerry Lee Lewis and ‘Pink Shoe Laces’ – it was all real commercial.”

When he was fifteen, he moved to Union City, Indiana, and expanded his musical skills by learning snare drums, tympani, and bass, while he was playing rhythm guitar in the high school swing band, which performed all the old, big band standards. During this time, the McCoys was formed, a trio that went through numerous changes of its own, alternately known as the McCoys, the Rick Z. Combo, Rick and the Raiders, and back again to the McCoys. One song, “Hang On Sloopy,” catapulted the group to fame (within a month after release, it was number one in almost every country in the world).

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

An up-and-down career kept the McCoys visible but a bit seasick, until Steve Paul made them house band for his club (the Scene), and the back-up band for Johnny Winter. To avoid further mispronunciation, misspelling, and misplacement, Zehringer changed his professional name to Derringer on the Johnny Winter And album. It’s stuck throughout his subsequent work with Edgar Winter, and is the name that appears on his own solo albums, the latest of which is Spring Fever (Blue Sky, PZ 33423).

What were your first guitars?

When I was about five years old I got a Stella acoustic guitar as a kind of a toy. I didn’t know that you could make music with it because I wasn’t really interested in it too much. My brother and I used to play with it a lot and paint our names on it, like country-western guys did. I must have been about eight when we finally culminated our whole experience with it by just crushing it and stomping on it, and breaking it into shreds. [laughs]

Right after that I realized that my uncle was a guitarist, and I got interested in playing the guitar myself. Then, for my ninth birthday, I got what I really consider my first guitar – a Harmony-ish kind of guitar. It didn’t really have a brand name on it, but it was an electric, one pickup, gold-painted guitar. [laughs]

And at the same time, I got a sleazy Gibson amp – I think it had one 12” speaker in it, an alligator kind of top, dark brown, and a tan bottom that had what’s called “aircraft covering.” Pretty good amp; I liked it. But it was great, because most parents, especially at that time before guitars were fads, for sure wouldn’t go out and get a brand-new electric guitar and electric amp.

I went through a lot of guitars. After I got that guitar, I learned everything I could about it. From then on, I was always trying to get a better guitar. I’ve always been a collector; zillions of guitars.

How is it that you got so turned-on to the guitar at age nine?

I’ve tried to figure that out a million times, but I can’t. All I know is one day I said, “Boy, what I want to do is play the guitar,” and my parents got it, and it was like total “into-it-ness.” Just instantaneous. That’s all I did.

Where did you get those first licks, off records?

Not at all. When I first started, I didn’t know you were supposed to learn specific licks. I didn’t know anything about that kind of stuff. I was just into learning how to play the guitar. It wasn’t a fad thing at all. In fact, it was very seldom heard as a solo instrument when I was nine. Electric guitars were just starting to become more of an “in” thing in rock and roll.

On the same day I got the guitar, my dad found out that a mechanic named Gene Fiely at Ford Garage in Fort Recovery, Ohio, where I lived at that time, played guitar. Gene was just exactly the way you’d picture a mechanic to be: Great, big, almost seven foot tall – great big huge guy with pock marks all over his face, but just the kindest, most gentle, jolly kind of great mechanic all the time. Dirt all over everywhere, in work clothes.

I went down to Gene Fiely's house and said, “I just got this guitar, and I know you don’t know me, but could you show me something on it?” So he showed me a big open G chord, and a D chord, showed me some ways to use them, some country song or something. I went home and played those chords, probably a thousand times at least that night, and went right back the next day to try to learn more. That’s basically how I got started, just learning chords.

Were there any musicians in your family?

I learned a lot from my uncle. But his style of playing was more of an old-fashioned chord style. He showed me whole songs, like “Liebestraum,” “Bye Bye Blues,” “Caravan,” and “Steel Guitar Rag.” But all those songs were never one-note things, like the vogue today. They were always chord songs, and so when I learned, I was always, for years and years, a kind of chord guitar player.

Once in a while a guitarist has to play a solo, but soloing was not why I got involved. It was to be a part of music. And that meant playing rhythm and chords, and I really considered myself – till now even – a rhythm guitar player.

What’s your studio and stage setup?

On stage, I use an Ampeg SVT amp with two four-twelve bottoms and Altec speakers.

Where do you set the tone and volume?

Volume about two o’clock. Tone: The treble with ultra-high on at about three-thirty, mid-range control in the middle position at twelve-thirty, and the bass control in the flat position at three o’clock. That won’t work for all guitars, because my guitar is a little brighter and a little louder than most.

What guitars are you using?

The ones I’m using on stage are made by Charlie LoBue at Guitar Lab [206 Thompson St., New York, NY].

I really considered myself – till now even – a rhythm guitar player

Rick Derringer

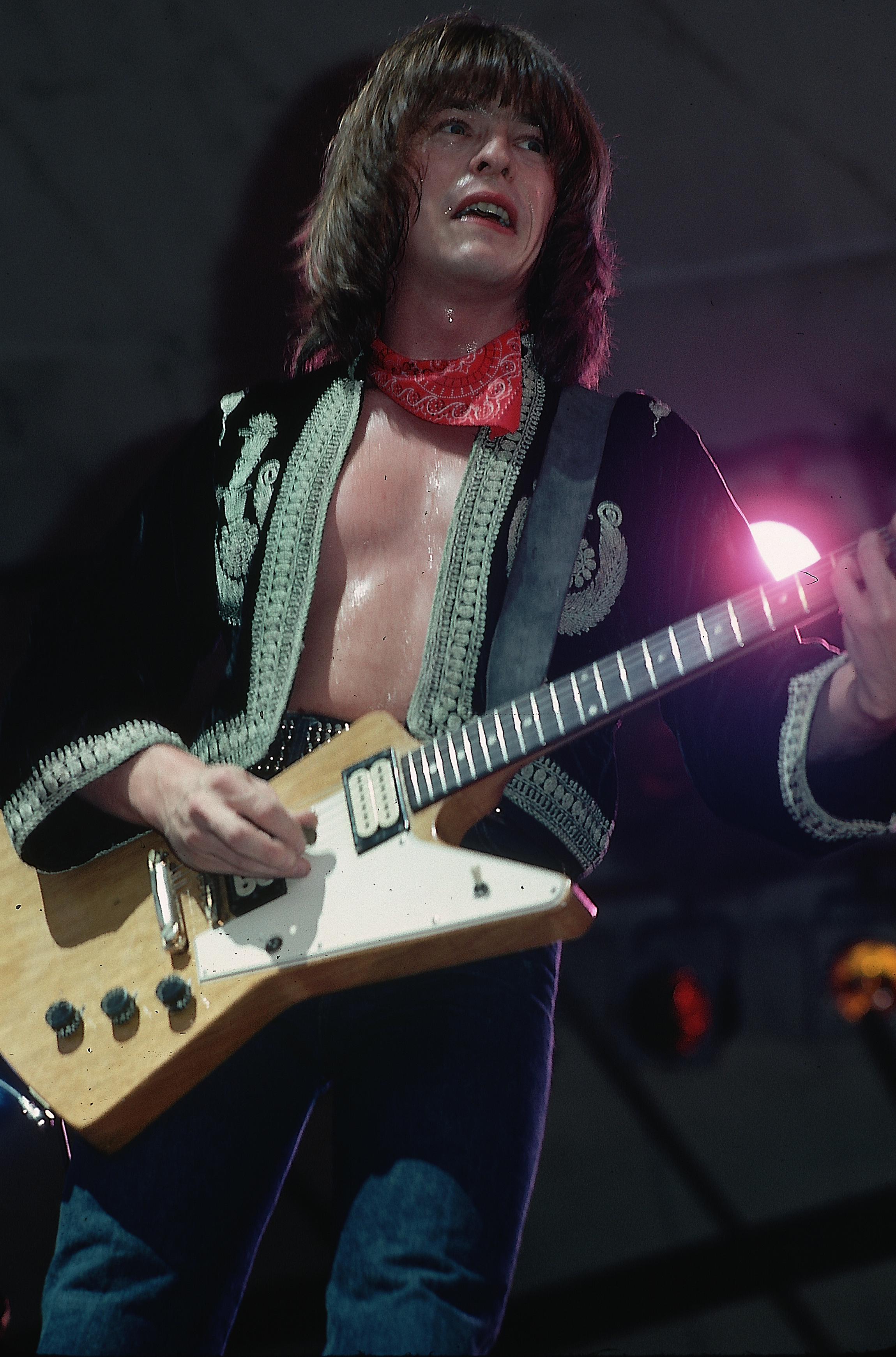

I didn’t want to take the chance of getting my real Explorer stolen, so I asked Charlie to make one that was similar, hopefully even a little better. So an Explorer copy it’s not. An Explorer body style is what it is. It’s got 22 frets joining the body at the 19th, and Gibson Schaller machine heads. In other words, styled after Schallers, but Gibson made them.

And it uses humbucking pickups, which are like the Explorer’s, but these are old ones. In this case, they’re rewound with a little better gauge copper wire and supposedly a little better magnet. And then all twelve poles are bored out, and screws are inserted so that they can be raised as high to the strings as possible. That creates a real loud, good-sounding guitar.

It’s also got some binding where Explorers didn’t, and it’s made out of birch, which is a real hard, heavy wood, so it had to be a little smaller than the Explorer in thickness, but it’s got a little more treble.

This guitar’s also different because it has a Schaller bridge, which offers more travel for adjusting the intonation. I believe in keeping that intonation adjusted. I adjust it every time I change the strings, or at least I check it.

The controls happen real quick on this instrument, and it has more treble than any other Gibson I ever had. But at the same time you get more bass and more output from the hole right here [points at output plug]: A loud guitar, in other words.

Where do you put the guitar’s controls?

I have a certain place I start, but I only use this as a starting reference, so it doesn’t really pay to say what those numbers are. But usually I start out with full treble – the guitar I use on stage only has one tone control – and the two volume controls both on.

How do you record the guitar?

Usually an amp is the only way to go. Very rarely, I put it through the board for some special sound. I have a definite feeling about that. It doesn’t sound good to me through the board, unless it’s an acoustic instrument which sounds great through a mike only.

Do you write music out with chord symbols and music paper?

No, I have it easy. I just write down the words, and I remember everything else.

Is it difficult for you to relate to the acoustic guitar?

I don’t feel that learning how to play electric limits you from knowing how to play an acoustic guitar. To me, it’s a joke. There’s no comparison. I’ve always played guitar, the same guitar as an acoustic guitar; electric requires all the same skill, maybe more.

What method do you use to tune?

I use those electric tuners to get close, and then I tune with my ear, using various methods: Chords, harmonics, the old [plays E, A, D, G, B, E] guitar book method, just anything I can do to make sure it’s in tune. It’s all real important.

It’s real important to be able to play in tune all over the instrument, and intonation plays a large part in that

Rick Derringer

The guitar’s a strange instrument in that the height of the nut makes it play out of tune at the first fret, but if the intonation is adjusted exactly properly on the G string, for instance, it will play sharp at the A note. Almost nothing you can do about it. So, in order to make it play as in tune as possible all over the place, I found that I have to compensate a little bit make the G string just a little flatter intonation-wise than is perfect so the A won’t be too far sharp, and so that my D won’t be too flat – and that’s just the G string! [laughs]

To me it’s real important to be able to play in tune all over the instrument, and intonation plays a large part in that, the height of the strings and of the nut has something to do with it – all those things are real important. Because I like to have a guitar feel exactly the same all the way up, I have the nut maybe a touch higher than some people would. The action’s set up so that everything can sit on the body, and you’ll be in business.

That also helps these pickups do their job. It’s loud; this particular guitar [his stage guitar] is more of an “in-person” guitar just because it’s designed to get the most out of personal appearances.

What sort of strings are you using?

Ernie Ball Super Slinkies with an unwound third.

Any fret work done?

Yeah, I like big frets better than the little ones because they allow me to hold onto the strings if you bend them. On Fretless Wonder-style guitars, you can slide up and down the guitar, and play real fast, and all that fantastic stuff, but if you go to bend a string it’s a simple law: If you press on a thin string with a finger and nothing to bridge that string between, when it gets to where it pulls, it’s going to slide right out from under your finger.

So, if you give two poles – which is what the frets are – a little more height, that offers somewhere for the string to go in your finger – pushes the string into your finger and enables you to hold onto it, so that you can stretch it real far and real easy. It never slides out from under your fingers.

How often do you change your strings?

About every three shows, on the road. In the studio a string will last longer.

Do you ever use anything else on stage?

I have a real Explorer, and that’s a nice sounding guitar, and I have a Les Paul that I like a lot. It’s about a ’58 Sunburst, with all white humbuckers. Pretty one, not modified in any way. It’s got big frets on it. I’ve got these frets on everything.

I learn solos note-for-note from records, and because of that I learn plenty of licks. I just try to use everything that I’ve heard

Rick Derringer

I have a Gibson 355. It’s about a ’58, or ’59. Big frets come on those guitars naturally. [laughs] I have another guitar by Charlie LoBue that’s a Honduras mahogany version with no binding. It sounds a little more like a Les Paul, and it might be a little more ideally suited to the studio, even though it’s not quite as good as the other for the stage.

I have a Strat that I use in the studio, usually for a specific kind of Stratocaster-sounding thing.

Do you practice systematically?

Yeah, all kinds of stuff: Chromatic scales, a regular major scale, a whole-tone fifth scale, and just stuff to keep my fingers moving and loose, so they don’t freeze up on me.

Of course, a lot of times I learn solos note-for-note from records, and because of that I learn plenty of licks. I just try to use everything that I’ve heard, to come up with music that fits whatever I’m playing.

Do you ever work for an improvisational feel during performance?

A lot. But I feel that people would like to hear some solos like they hear them on the radio, so I just play the solos from hits exactly like they were, though I do try to play them as good as they can be played every night. Other than those few songs, when it comes to a solo, that is an improvisational section.

Where do you get your licks?

Probably it started out from chords – knowing a combination of those structures and patterns, then growing into scales, and then into a more correct knowledge of musical theory. I try all the time to go toward being totally fluent.

In other words, some people can create exactly what comes into their minds instantaneously with their voice. In my mind, the ideal point to get to on the guitar is where you don’t have to think about scales, keys, notes, harmonic structures, none of that stuff. You can just play music fluently. It’s a hard place to come to, but that’s what I’m trying to do.

Did you ever sit down and actually study theory?

Not too much. It always seemed like too much work for me. My teachers were usually piano teachers, and they really didn’t know much.

Did you listen to anyone in particular to learn?

Everyone in particular. Always, always. Every time I listen to a guitar, I’m in there listening for something that I’ll want to remember and play myself, or I’m listening for something that I’ll want to forget and stop playing.

What about your pick?

Right now I’m using these heavy, triangular-shaped ones made by Pastore [507 32nd St., Union City, NJ 07087]. On stage, for that extra rock and roll flair, I keep “zizzing” my strings with my pick [moves pick up neck from tailpiece towards nut]; and since the strings are rough, every time you ziz one real hard you grind down that pick, and the next time you start to play, it will actually catch and hold onto the string. So I just toss them out into the audience.

I have this piece of tape going clear across the top of my amp with these picks all lined up. [laughs] So it’s real slick: I can just toss one out there, reach over, and grab another one instantaneously.

Every time I listen to a guitar, I’m in there listening for something that I’ll want to remember and play myself,

Rick Derringer

How many do you use a night?

Ten or fifteen sometimes. At home or in the studio, unless I want to add one of those rock and roll zings – I don’t use as many. I can use one for a long time, as a matter of fact. At home and in the studio, I have favorite picks without the ziz marks in them, though they’ve been carefully crunched up by my teeth, [laughs] so that they have a rough edge that has been acquired over a long period of time, but that will not catch the string, and that also enables me to hold onto them a little better. They’re so carefully roughed, that sometimes if you use the wrong end, they give a real nice rough sound.

How do you hold your pick?

Thumb and first finger. The way they show you in the books. If I’m not on stage, I keep my hand on the bridge, so I can mute when I want real good control. On stage, when I want to be more of a showman than a guitarist, and I’m doing those Pete Townshend arm flails, my arm doesn’t actually rest on anything as much. But there is something to be gained by that, too. You can go faster.

Are you alternating your picking up and down?

Yeah, but not always anything. Not ever any kind of absolute. Always just whatever gets the sound that I’m particularly wanting to get at that time. And the sounds I want vary. Pick up on a string, it gives you a sound. You pick down, it gives you a sound. Play high, it’s a sound; play near the bridge, it’s another sound. There are a zillion different things. You can add all three fingers plus the pick. Really, “anything goes” is the way I play.

What about your left hand?

I use all four fingers – thumb, when it’s necessary, because lots of chords involve the thumb. I read a lot of times that you’re not supposed to use your thumb, but I feel that anything goes. Use your fingers for anything you need at all times.

I started out barely using my little finger at all, but eventually I got to the point where I had to start using my little finger more because I could play better using it.

You play slide?

Yeah, I play in standard open E tuning just like an open E chord. I use a metal bar on my little finger so I can play with my other fingers. I used to get them made at a plumbing shop because that was a heavier bar, and I could get exactly the size I wanted for my finger and have it polished down real nice. But they either always get lost or stolen, so right now I’m just using a bar like you get in a music store. Since they’re a little big for my finger, I put masking tape in the inside, so that it’s actually kind of form-fitted inside and allows my finger to bend a little.

Johnny [Winter] showed me a lot. To me, he’s one of the best exponents of the slide guitar. I played it a lot in the McCoys when we were travelling. One time, in fact, Johnny and I were with Duane Allman. I didn’t feel much a part of it. I felt, “Here I am, a young kid playing with these guys that have been into country blues all their lives,” but I was having fun playing along.

I play in standard open E tuning just like an open E chord. I use a metal bar on my little finger so I can play with my other fingers

Rick Derringer

At one point Duane said, “By the way, I’ve been meaning to tell you. I came down when you were at the Image in Miami, and you were playing slide guitar on some song. I just wanted to tell you that you were the person at that time that made me think, ‘Wow, it’s amazing; that slide can make some real good rockin’ music.”

I thought this guy’d been interested in it all his life. But he said that I was one of the people who made him become more involved in slide guitar. I only used it on one lousy song, and here Duane is telling me all this, and he becomes real famous for slide guitar. It was great; I loved it.

How do you get your vibrato?

Where I was from and the music I played, people didn’t know much about bending strings. I hadn’t heard anything about Django Reinhardt records where he was bending them, so I just didn’t know anything about it, never learned about it. But eventually I learned, and realized that you could also do vibrato.

It was really hard for me to develop vibrato, because I’d never done it. Kids nowadays, that’s all they’ve heard. They pick up the guitar, and say, “I can’t play it, but I can try that vibrato,” so they know it from the beginning.

For a while, my vibrato was too fast. It’s hard to slow it down. I do it all different, never with the little finger. Always one of the first three. I bend down only if I’m playing one of the low strings, where I would run out of neck if I bent up.

What sort of pedals and devices do you use?

On stage, I use a Vox wah-wah and MXR Phaser. That’s it. In the studio, anything that I can find, and everything that I like. I go up to Manny’s [I56 W. 48th St., New York, NY I 0036] and find all the new gadgets and gimmicks for guitar. I try to discover one that sounds cool that maybe people haven’t heard much.

I like to try out all those things: Doublers, phasers, Leslie simulators, Tone Benders, and octave devices, and all those things with synthesizers. I have a Mu-Tron at home, speakers in bags. The one I have right now is the one that’s advertised as the [Heil] Joe Walsh talk box. I’ve used that on some of my records. As a matter of fact, I’ve used Joe Walsh’s. He loaned me his. It’s homemade, not one of those manufactured ones.

What other instruments are you playing?

I really enjoy playing bass. I see it as a totally separate instrument. I really like to keep it from sounding like a guitar as much as possible. To me, that’s the challenge: Playing it like a bass rather than a guitar. And it’s fun to do.

Do you ever just step on a pedal to beef up a solo?

I try not to, ever. I try not to feel like I’m playing less than inspired, though to me it’s kind of an ideology that you can never really truly play inspired, because a musician is a human being playing something that comes from somewhere.

Inspiration is the idea we like to work towards, so I’m always trying to play at my utmost and as inspired as possible. That’s the whole challenge in being a guitar player

Rick Derringer

But inspiration is the idea we like to work towards, so I’m always trying to play at my utmost and as inspired as possible. That’s the whole challenge in being a guitar player. Every time I play on stage or on records or just fooling around, I’m trying to play and learn and do it well, be happy about it, have fun doing it, and not ever feel bored or like it’s a job, or staid, or any of those kind of words.

Do you think you’ll be playing guitar thirty years from now?

My personal goal is just to make the next thirty years, or the next fifty or ninety years, and to make them as long and as happy as possible along the way. I like to play the guitar. I’d like to continue doing that as long as I can.

I admire people like Picasso especially, because he’s a man who was really doing something he liked all his life, and even though he must have had hard times like everybody, he stayed very active, stayed very free and happy and with a youthful spirit, enjoying life as much as possible till the day he died.

And that’s the kind of person I’d like to be. I’d play the guitar; I’d like to keep learning and working at it and doing as well as I can forever, with the same kind of youthful spirit about it and energy and enthusiasm that I had the day I got my first instrument.

Was there an abrupt change in your musical growth after “Hang On Sloopy,” when you started touring?

No, in fact I think touring is one of the ways you actually get better at playing the guitar – at least with me. Before “Hang On Sloopy,” there was always the temptation to play music that didn’t really develop me or my dexterity as a musician.

At home, I have a tendency to play real simple music or just music that I like that I may have played before many times, not necessarily trying to get a lot better or improve my dexterity. But on the road, it’s a different kind of thing. You’re on stage trying to impress people as well as play good music.

Every time I go out on the road, I feel that my dexterity improves a lot, and as a result my way of thinking about music is improved, because whatever comes into my head as a human being I feel other humans would like. It’s much easier for me to get that out and get to those other human beings because my dexterity has improved.

If you want to be a guitarist, it takes a long time and a lot of work

Rick Derringer

I look at playing on the road as real good practice. Even though I might only pick up the guitar a couple of times a day for ten minutes each time, that night I’m going to have to go out for an hour and a half and play real good.

My whole way of playing on stage is trying to play better than I did the night before. If you’ve done a song enough times so that you don’t have to worry about remembering it, a framework is established, and you can just use that song as a vehicle to create, because you’re playing something you know so well that you have the time to consider new things to do with it.

Do you have advice for guitarists just starting out?

If you want to play guitar, it isn’t something that comes overnight. We’ve been talking about nineteen years of a whole lot of different stuff, and I’m still trying to get better and explore new regions that I hadn’t even thought about. It’s not something where you just pick up a guitar and think, “Well, I’ll just learn six solos, and I’ll know six songs.” You can do that, but that doesn’t necessarily make you a guitarist. It makes you a guy that can play six solos. But if you want to be a guitarist, it takes a long time and a lot of work.

Guitar Player is the world’s most comprehensive, trusted and insightful guitar publication for passionate guitarists and active musicians of all ages. Guitar Player magazine is published 13 times a year in print and digital formats. The magazine was established in 1967 and is the world's oldest guitar magazine. When "Guitar Player Staff" is credited as the author, it's usually because more than one author on the team has created the story.