Need to Add Some Spice to Your Melodies and Solos? This Lesson on Chromaticism Will Give You Food for Thought

Learn how to use non-diatonic “outside” notes for tastier licks in jazz and other styles.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

As we improvise or compose melodies, we learn that repeating and developing a motif, or phrasing idea, can lend structural cohesion to the music and help it “make sense.” It also can have the benefit of grouping notes into easily workable chunks.

How we use scales to create these usable melodic fragments is a pretty wide-open topic. To the ear, playing the notes of the underlying chords, using arpeggios, will always sound correct and pleasing, and regardless of where you start within the framework of the key, your ear should guide you to those correct sounds, with the related scales tones serving as transitional “fill.”

For example, if we’re in the key of C major, and the chord of the moment is Dm, playing a simple ascending fragment of the C major scale (C, D, E, F, G, A, B) starting on D renders the sound of the Dorian mode (D, E, F, G, A, B, C), which neatly agrees with the Dm chord and touches upon its structural notes – D, F and A.

And if we move on to a G chord and continue to play within the C major scale, starting on G, that gives us the G Mixolydian mode (G, A, B, C, D, E, F) and the chord tones of G – G, B and D – which makes the note choices sound correct.

This kind of methodical, diatonic (scale-based), “hit-the-right-notes” approach is all well and good, in terms of learning how to avoid stepping on harmonic-melodic landmines and hitting “bad” notes, but without any daring detours taken, it can make for a rather bland and “safe”-sounding melody that isn’t very dramatic or compelling.

One effective way to color and spice-up a melody to make it more interesting is to incorporate chromaticism, which refers to the use of non-diatonic tones from the 12-tone chromatic scale that are outside of the key you’re in.

A lot of improvisational studies in jazz education curricula teach you how to use all the notes in the chromatic palette and, in effect, make them all sound musically justified, usually through resolution, using the conceptual tactic of tension and release.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Oftentimes a resolution is effectively achieved by moving from a chromatic, or “outside,” note to a neighboring chord tone or related scale tone, as the ear ultimately gravitates toward pleasing, consonant sounds for a final or conclusive-sounding cadence.

In this lesson, we’ll present some effective and useful options for injecting chromatic notes into otherwise diatonic lines, using motifs based on a foundational interval pattern, which will serve as our working template.

BROKEN THIRDS

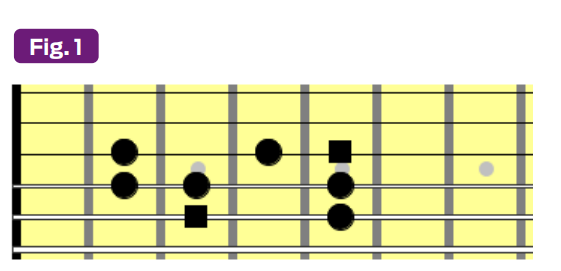

Fig. 1 illustrates a one-octave fingering pattern and fretboard shape for the C major scale in 2nd position, which we will use as a starting point.

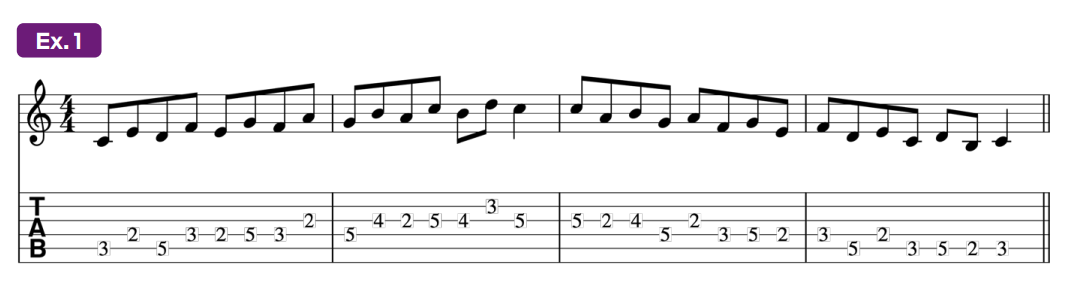

Ex. 1 shows the scale played in what’s called a “broken-3rds” melodic pattern of eighth notes that groups the notes into pairs, or two-note “cells,” and follows a climbing pattern that goes up two scale degrees – what’s known as a 3rd interval, which can be either major (two whole steps) or minor (one and one half steps) – then drops back down one scale degree – what’s known as a 2nd, which can be either major (one whole step) or minor (one half step) – before ascending another 3rd, ultimately rising through the scale.

In bar 3, after reaching the octave C root note, the cell pattern reverses, and a cascading melodic contour unfolds, with the notes now going down a 3rd, up a 2nd, down a 3rd, up a 2nd, etc., which brings us back to our starting low C note.

Notice that the exercise adds one higher note (D) and one lower note (B) to the shape shown in Fig. 1. This is done for the sake of making the line sound melodically complete.

Adding chromaticism to a line like this can generate melodic momentum and drive and make it sound more intriguing. So let’s take this C major scale broken-3rds pattern and look at some ways to spice it up, or jazz it up, by applying targeted chromaticism.

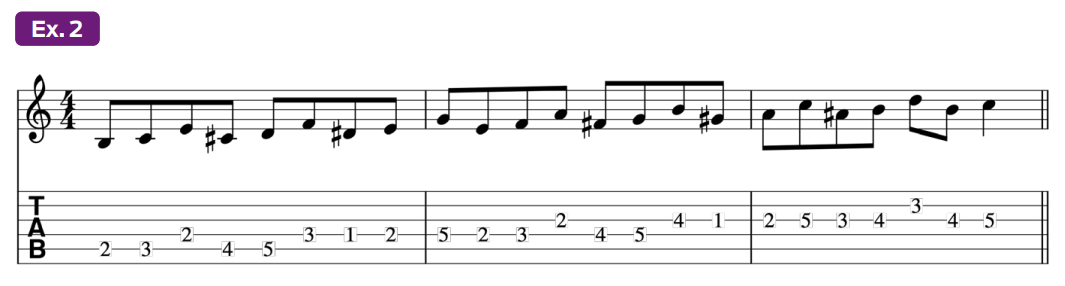

Ex. 2 adds a chromatic “lower neighbor” approach tone to each cell that leads up to the first note and injects a moment of tension and release.

Notice that, in doing this, we’ve also expanded each cell to three notes.

Since we’re still playing eighth notes, this creates an interesting rhythmic twist, as we now have a “threes-on-twos” syncopation pattern within the melodic contour, with shifting accents and the chromatic notes falling on varying beats and upbeats throughout the three-bar phrase.

Ex. 3 applies the same approach to the descending part of our original broken-3rds pattern from Ex. 1, again leading into each cell from a half-step below and creating an interesting rhythmic syncopation to go with the chromatic tension and release.

Notice that we now have a repeated note in two spots, the E in bar 2 and the low B in bar 3.

Also, due to the different melodic contour here, the chromatic notes function as passing tones.

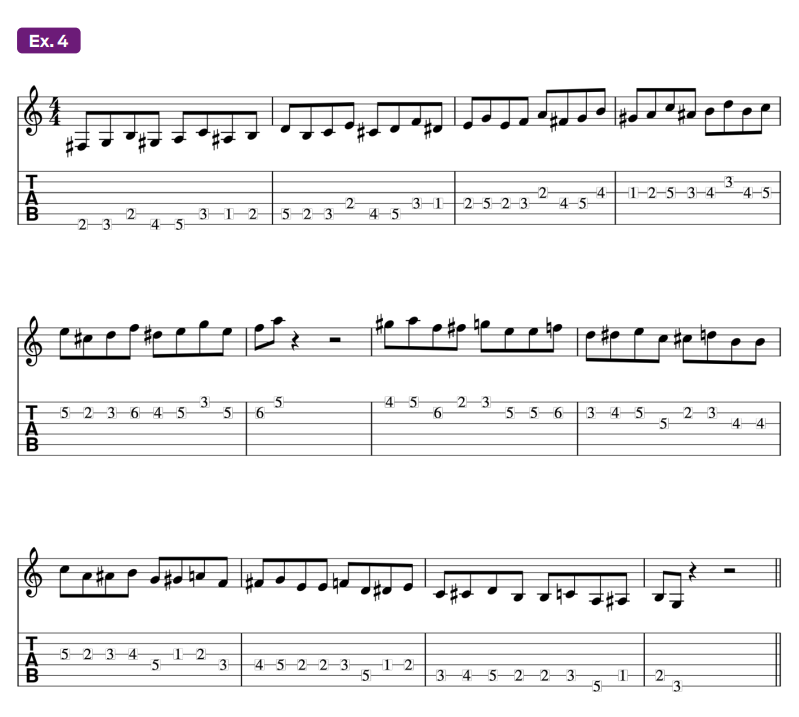

Now, if we expand our foundational 2nd-position C major scale fretboard pattern to include all six strings, we get the larger note set and shape illustrated in Ex. 4, which now spans over two octaves, from a low G note to a high A.

This pattern may also be thought of as the relative G Mixolydian mode, or, for that matter, any of the seven modes of the C major scale: C Ionian, D Dorian, E Phrygian, F Lydian, G Mixolydian, A Aeolian and B Locrian.

Fig. 2 shows the adding-lower-chromatic-neighbors device from Examples 3 and 4 now applied to our expanded six-string fretboard shape, both ascending and descending.

Notice how, in bars 1–6, the chromatic pitches function as approach tones, and in bars 7–12 they serve as passing tones.

Taking the concept a bit further, we can create a three-note cell in which the third note reiterates the first.

Ex. 5 illustrates this idea, applied to the basic C-major-scale-in-3rds pattern from Ex. 1.

Notice that the rhythmic motif for each cell is now two eighth notes and a quarter note.

If we were to connect the starting notes of these three-note cells with chromatic pitches, it would certainly add interest to the above line, as demonstrated in Ex. 6.

Because the structure of the major scale includes some whole steps (two frets) and half steps (one fret) between adjacent notes, there are two techniques required to accomplish the chromatic connection.

The majority of cells are connected by a chromatic passing tone: C - C # - D, D - D # - E.

Others, namely the ones beginning on F and C, are approached by a chromatic pitch one half step above the targeted scale tone, followed by the diatonic pitch one half-step below.

This is an example of an interesting melodic device known as chromatic enclosure, which has been widely used in classical music since the mid-19th century.

That usage then influenced the vocabulary of jazz guitar.

Ex. 7 replaces the eighth rests from the previous line with the missing second note of each three-note group from Ex. 5, keeping the chromaticism intact.

Ex. 8 applies the same device to a descending pattern, with descending chromatic passing tones now used.

We can replace the rests from the previous example with the second note of each three-note group, from bars 5-8 of Ex. 5, keeping the chromaticism intact, as demonstrated in Ex. 9.

PLAYING OVER CHORD CHANGES

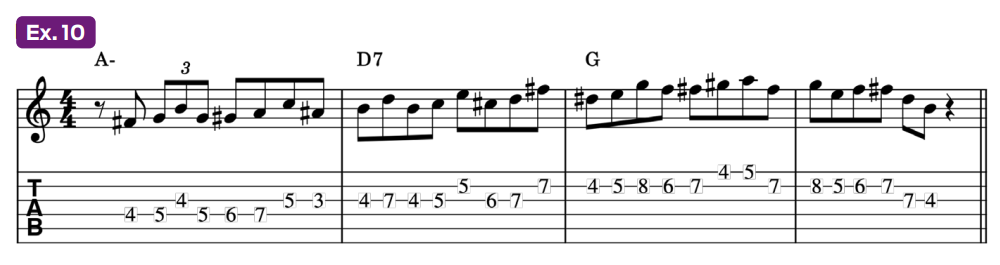

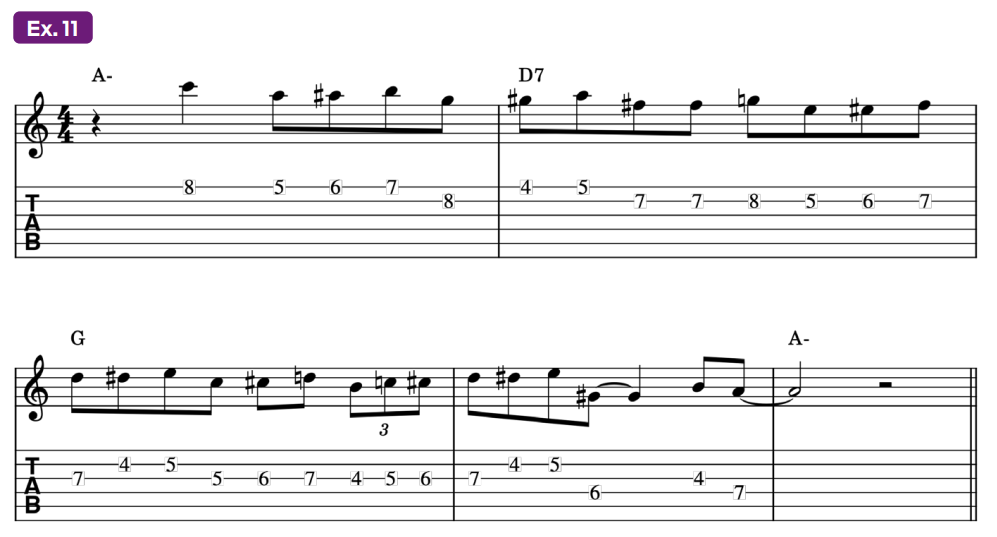

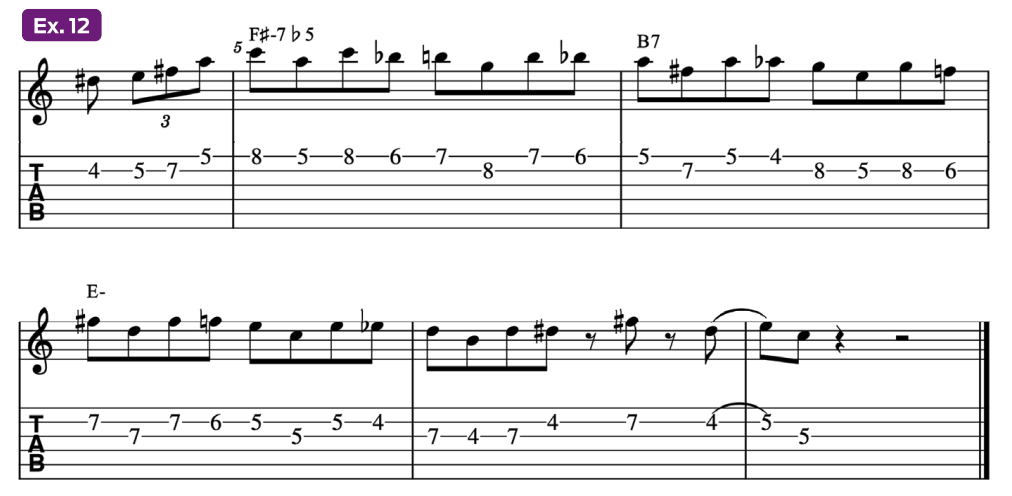

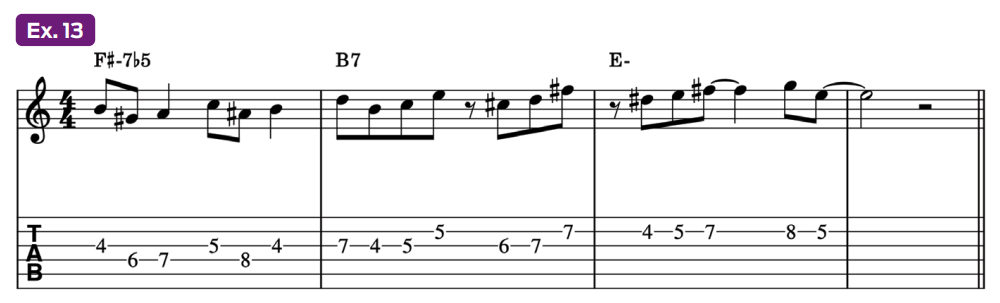

Our next group of examples demonstrate how to apply these chromatic devices – approach tones, passing tones and enclosure – to changing chords, using parts of the chord progression to the jazz standard “Autumn Leaves.”

The first two examples are in the key of G major and follow a ii - V - I progression (Am7 - D7 - G).

The final two examples are played in the relative minor key of E minor (per the tune’s bridge section) and follow a ii - V - i progression in that key (F# m7 b5 - B7 - Em).

In Ex. 10, the first three bars utilize ascending elements from the basic concepts introduced in Examples 2 and 7, with some jazzy phrasing added (note the use of the eighth-note triplet in bar 1).

Ex. 11 is a descending phrase similar in construction to Ex. 3...

...and the descending E minor phrase in Ex. 12 applies the concept from Ex. 9.

Finally, the line in Ex. 13 takes the phrasing pattern from Ex. 2 and adds some interesting variation, by rhythmically displacing the three-note cell, so that the notes fall on different parts of the beat (beginning with the fourth note in bar 2).

We hope these chromatic concepts have given you some useful musical food for thought.

Apply them to your own single-note lines and see what kinds of interesting variations you can come up with, using your ears to guide you.