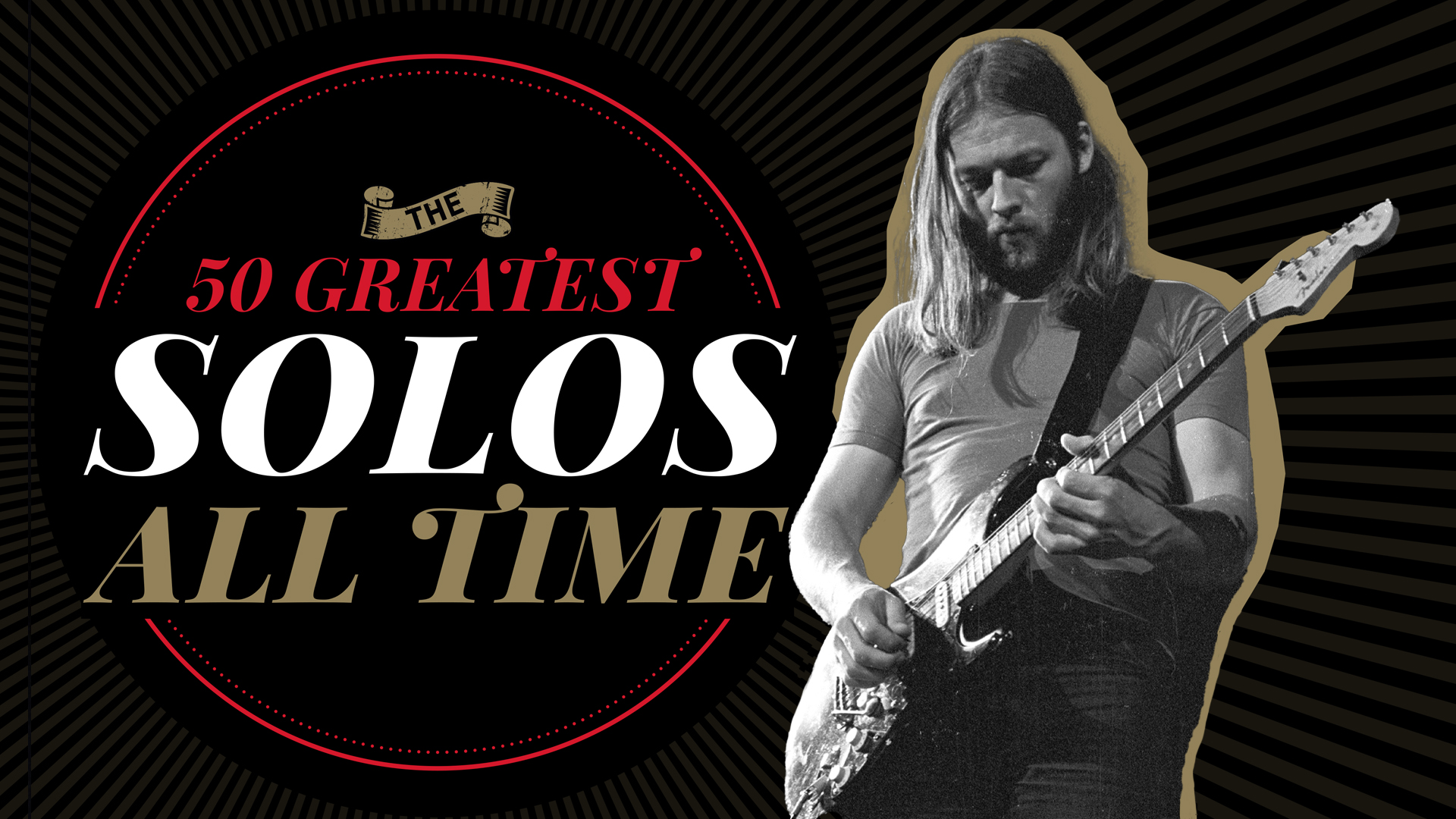

"They sort of appear as if they are out there in the air. The best ones do. But I don’t know how they get there." David Gilmour talks soloing in Guitar Player's guide to the Greatest Guitar Solos of All Time

Behold the genius of Gilmour, Jimmy Page, Jimi Hendrix, Eddie Van Halen, Brian May and many more — as voted by the readers of Guitar Player

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The thorny subject of the greatest guitar solo of all time has long been a fiercely contested debate, probably because every solo is different. How do you compare, say, “Comfortably Numb” with “Crazy Train,” or “Stairway to Heaven” with “Sultans of Swing”? It’s impossible. Still, public opinion ebbs and flows, and we wanted to find out which solos currently rank among our readers as the greatest of them all.

So we ran a poll on GuitarPlayer.com to find out and here we present the results. We’ll take a look at the stories behind the songs and find out just what made those lead guitar breaks so great through conversations with Brian May, Kirk Hammett, Michael Schenker and others.

20. Gary Moore | “Still Got the Blues”

GUITARIST: GARY MOORE (1990)

The definitive blues guitar ballad.

Presented as the title track from his 1990 album, this wistful tune in A minor became Gary Moore’s calling card fairly late in his career, when he reinvented himself as a blues artist. There’s a point in the solo where you can hear the Belfast great switch from the neck humbucker to the bridge on the 1959 Les Paul Standard he nicknamed Stripe and start deviating from its main theme, mainly sticking within the A minor pentatonic scale, with a few notes from the Aeolian and harmonic minor scales.

Moore was plugged into his prototype Marshall JTM-45 reissue head with one of the company’s newly designed Guv’nor distortion pedals out in front. More than 30 years later, this remains one of the most raw and expressive blues tracks, with Moore almost fighting his guitar at points, yet never failing to deliver the goods

19. Metallica | “Fade To Black”

GUITARIST: Kirk Hammett (1984)

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Metallica’s first ballad features some of Kirk’s most epic playing.

Recorded at Flemming Rasmussen’s Sweet Silence Studios in Copenhagen in February and March 1984, Ride the Lightning, Metallica’s sophomore album, was more progressive and stylistically greater in scope than the all-out thrash assault of their debut, Kill ’Em All. That change is evident on “Fade to Black,” which features acoustic guitars and a nonstandard structure more akin to the “Stairway to Heaven” school of songcraft. But it is the song’s timeless melodic solo that most vividly signals a stylistic shift in guitarist Kirk Hammett’s playing. And the signature element he employs for the last solo is arpeggios.

“I have been playing that song for so long now,” Kirk tells our sister publication Total Guitar. “For the very last solo, I know how I want to start it, but then I am in an area where I can improvise for 16, 18 or 24 bars, and then [drummer] Lars [Ulrich] will hit a certain fill, which means that it’s up and it’s time for the arpeggio part. And then I just slide right into those arpeggios.” And they are arpeggios played on two strings, Hammett specifies. “When guitar players first started incorporating arpeggios into their playing, before the whole Yngwie sweep-picking thing, arpeggios were played on two strings – not three or four strings,” he explains. “And that was what the vogue was at the time in the 1980s, so I have been playing those for a long time. I use my middle finger just to anchor my position on the neck.”

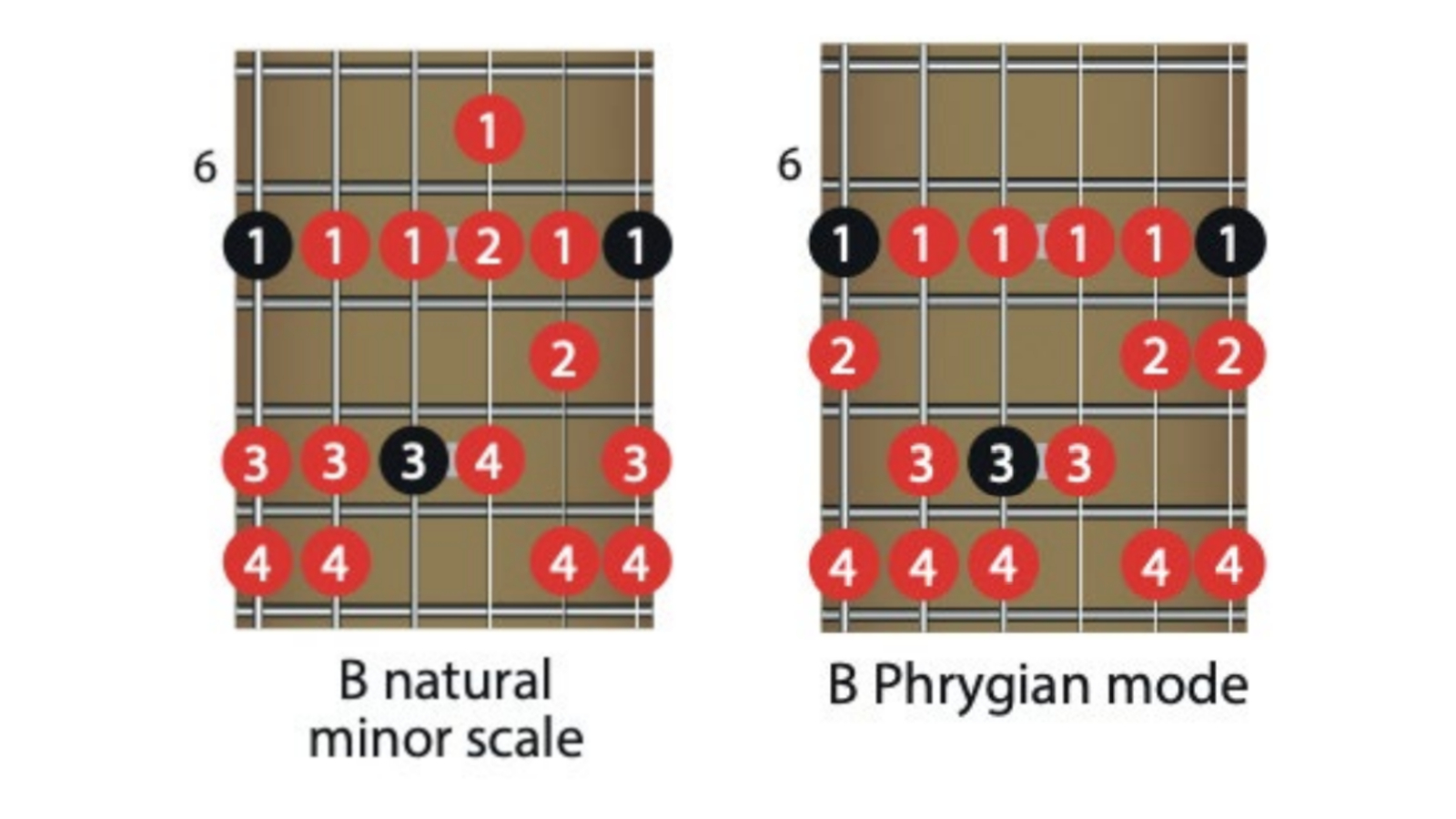

That’s a great tip from the man who plays the solos. But how should you tackle them yourself? First, there are two essential scales you’ll need to know: the B natural minor scale and the B Phrygian mode, both shown below. These cover you for the entire opening 30 bars, which, let’s face it, is a lot of music, so this is a good reason to learn a couple of shapes if ever there was one.

To make it simpler, most of your time is spent in the natural minor scale. Not until around bar 20 will you find yourself briefly landing on the C note, which appears in the Phrygian mode. The bottom line is that Hammett improvises this part of the solo live – and these are the shapes he uses.

Up next are those two-string arpeggio shapes, and they’re 16th notes – all of them! At 142 bpm, it’s pretty fast, but Hammett doesn’t pick every note, opting to use pull-offs to make those rapid licks easier. It’s definitely something to experiment with and if you’re still struggling, you could try adding in an occasional hammer‑on, too.

18. Steely Dan | “Kid Charlemagne”

GUITARIST: Larry Carlton (1976)

Messin’ with the “Kid.”

Steely Dan’s catalog is filled with remarkable guitar solos, but Larry Carlton’s brilliant work on The Royal Scam’s “Kid Charlemagne” remains the most celebrated. Carlton strings together a series of tasty phrases that follow the underlying chord changes with a blend of inside and outside playing that is technically mind bending and emotionally satisfying.

“I was pretty familiar with the tune, so I just improvised,” he tells Guitar Player. “People think I’m kidding when I say that, like I had worked the solo out beforehand, but I didn’t. It was straight improv, and it worked.” Very well, in fact. Perhaps more has been written about his solo than of the song itself.

Despite the acclaim, Carlton was, and remains, nonplussed. “When the record came out, there was a wonderful review of the tune in Billboard and they raved about the solo,” he says. “I put the record on and listened to it with my wife, and at the end of it I said, ‘I don’t know. It just sounds like me.’”

17. Cream | “Crossroads”

GUITARIST: Eric Clapton (1968)

The finest rock and roll cover of an acoustic blues song.

It started as a blues tune called “Cross Road Blues” by Robert Johnson and became one of the finest examples of natural ability, soulfulness and showmanship from a virtuosic 22-year-old guitarist named Eric Clapton. His reimagining of the song as “Crossroads” further cemented a legacy that by then had earned him the nickname God.

Famously recorded at San Francisco’s Fillmore West venue for supergroup Cream’s Wheels of Fire album, Clapton’s arrangement retains the soul and spirit of Johnson’s original but updates it for a contemporary audience raring to cut loose and be entertained by dazzlingly quick, passionate musicianship.

Remarkably, Clapton is no fan of the performance: He complains that the band lost the “one” in the first verse of his second solo break, thereby throwing off his phrasing. That’s perfectionism for you. For everyone else, this four-minute track remains a source of fascination more than 50 years on.

16. Eric Johnson | “Cliffs Of Dover”

GUITARIST: Eric Johnson (1990)

Heavenly tones from the Texan great.

This instrumental won Eric Johnson a Grammy for its exquisitely tasteful guitar playing and jaw-dropping tones. For the recordings, the Texan musician mainly stuck with his early ’60s ES-335, though he chose to use his 1964 “Virginia” Strat for the opening lead and parts of the main solo. The guitars were fed into a 100-watt Marshall Super Lead, with an Echoplex and BK Butler Tube Driver to help achieve those smooth, violin-like tones and warm sustain.

“I first heard him in 1986 on Live at Austin City Limits,” Joe Bonamassa told us in 2015. “It was ‘Cliffs of Dover,’ and it was just terrifyingly good guitar playing. I wasn’t even sure if it was real! Then I saw him live, and his tones were the best I’d ever heard. I wondered how this guy was getting all of these sounds out of his Strat. I’d never seen anybody have such a forward-thinking rig like that.”

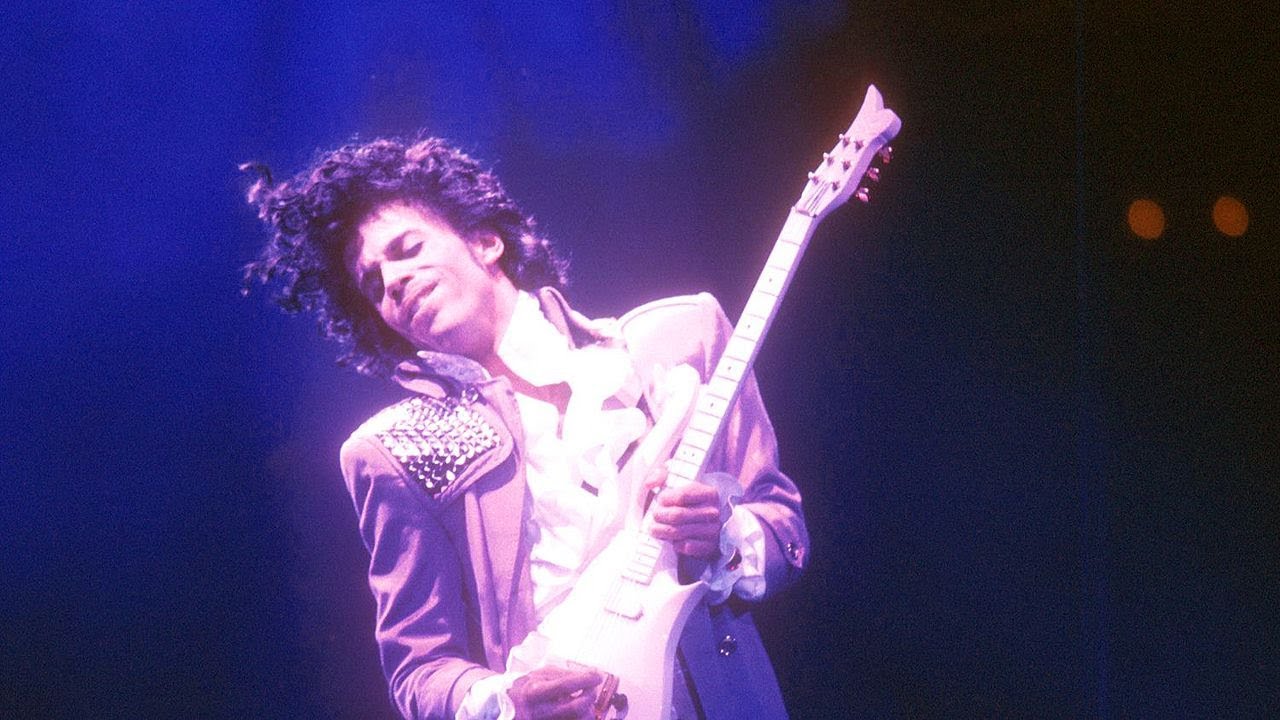

15. Prince | “Purple Rain”

GUITARIST: Prince (1984)

The Purple One’s defining guitar moment.

The epic outro to “Purple Rain” – which takes up nearly two thirds of the song itself – stands out as some of Prince’s finest work on the six-string, wailing away in G minor pentatonic and occasionally including some more modal notes, like the minor 6th. There’s also that repeating motif that dances around the 2nd and minor 3rd intervals.

It’s simple and effective, setting things up for the vocal melody that comes in toward the end. It’s not a busy solo by any means. Rather, the Purple One chose to leave a lot of space in between the lines he played and focus on big hooks instead of monster licks.

Prince would extend the solo for up to 15 minutes in live performance. While there are many great live renditions of this track, his half-time performance for 2007’s Super Bowl in Miami is the stuff of legend. Shredding alone onstage in the middle of a storm, Prince seemed to be living the moment for which this song was written.

14. Deep Purple | “Highway Star”

GUITARIST: Ritchie Blackmore (1972)

Race with devil on English highway.

“I wrote that out note for note about a week before we recorded it,” Ritchie Blackmore said of his remarkable and most definitely memorable solo to “Highway Star.” “And that is one of the only times I have ever done that. I wanted it to sound like someone driving in a fast car, for it to be one of those songs you would listen to while speeding. And I wanted a very definite Bach sound, which is why I wrote it out – and why I played those very rigid arpeggios across that very familiar Bach progression – D minor, G minor, C major, A major. I believe that I was the first person to do that so obviously on the guitar, and I believe that that’s why it stood out and why people have enjoyed it so much.

“Over the years, I’ve always played that solo note for note, but it just got faster and faster onstage because we would drink more and more whisky. [Keyboardist] Jon [Lord] would have to play his already difficult part faster and faster, and he would get very annoyed about it.”

13. Guns N’ Roses | “Sweet Child O’ Mine”

GUITARIST: Slash (1988)

A game of two halves.

Slash’s solo on this Guns N’ Roses breakthrough single is rock guitar at its finest. The first half is laid-back and modal, built around the Eb minor scale with a few major 7ths thrown in for a harmonic-minor flavor. The second half is much more aggressive and bluesy, and sticks mainly to position one of the pentatonic scale an octave up the neck in the same key. The bends feel that much wider and the vibrato more pronounced.

Slash plays the first section on the neck pickup for thickness and warmth before switching over to the bridge for more bite, with his Cry Baby engaged. Perhaps most impressive is his off-the-cuff sense of feel and how he strings it all together, which is the mark of any great guitar solo. Remarkably, although Slash’s riff was responsible for the song’s creation, he wasn’t fond of the song originally. “We were a pretty hard driving band, and that was sort of an uptempo ballady type of a thing,” he said. “So it’s grown on me over the years.”

12. Ozzy Osbourne | “Crazy Train”

GUITARIST: Randy Rhoads (1980)

Fretboard fireworks galore on Ozzy’s Blizzard of Ozz comeback.

The Double-O has often cited Randy Rhoads as the man who saved his career – and when you hear the solo on “Crazy Train,” you understand why. Although Rhoads’ classical- and modal-based approach was far from Tony Iommi’s blues leanings, he was, like Ozzy’s old bandmate, a true inventor.

There’s a section toward the end of this solo that actually sounds like a train squealing off the tracks, thanks to the use of a chromatically ascending trill that then descends in key. Rhoads concludes the solo with a fast-picked F# minor pentatonic phrase before a rapid Aeolian legato run ending with a big bend on the 19th fret.

The shredder performed the solo with his customized Jackson guitar through a Marshall and a couple of 4x12s while sitting in the control room. “We’d plug the guitar directly into the console,” recalls Blizzard of Ozz engineer Max Norman. “We’d preamp it in the console and send it down to the amp from there. That way we could control the amount of gain that hit the amp.”

11. Michael Jackson | “Beat It”

GUITARIST: Eddie Van Halen (1982)

Breathtaking results from an unlikely pairing.

Asked to contribute guitar to Michael Jackson’s Thriller album, Pete Townshend declined but offered a suggestion: How about Eddie Van Halen? Jackson and producer Quincy Jones thought that was a great idea, and got Ed onboard to play the solo to “Beat It.” But after hearing the part where he was asked to solo, the guitarist was unhappy with the chord changes and had the engineer edit the tape to create a new pattern that better suited what he had in mind.

Ed knew Jackson might be surprised and possibly unhappy with his executive decision. “So I warned him before he listened,” he told CNN in 2012. “I said, ‘Look, I changed the middle section of your song.’ Now in my mind, he’s either going to have his bodyguards kick me out for butchering his song, or he’s going to like it. And so he gave it a listen, and he turned to me and went, ‘Wow, thank you so much for having the passion to not just come in and blaze a solo but to actually care about the song and make it better.’” And he did it for free.

10. The Beatles | “While My Guitar Gently Weeps”

GUITARIST: Eric Clapton (1968)

An uncredited Slowhand makes a rare guest appearance with the Fab Four.

By 1968, George Harrison was penning compositions that rivaled those of his bandmates John Lennon and Paul McCartney. “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” was every bit as good as anything his musical partners wrote, but no one could get up the enthusiasm for it, so Harrison invited his pal Eric Clapton to play on the session, knowing it would put the Beatles on good behavior.

Using Harrison’s 1957 “Lucy” Gibson Les Paul through a Fender Deluxe amp, Clapton doesn’t so much mimic the haunting, aching main melody as he creates a harrowing song within a song. His descending bends and release notes, and that inimitable vibrato, are on full display and are appropriately tear-jerking, weaving a dramatic narrative that builds to a shattering climax.

9. Chicago | “25 OR 6 TO 4”

GUITARIST: Terry Kath (1969)

Wah-drenched ecstasy.

This magazine once described Terry Kath’s “25 or 6 to 4” solo as “Wes Montgomery meets Jimi Hendrix,” and it’s a fair point, as Kath was influenced first by jazz and, later, hard rock. As a founding member of the jazz-rock band Chicago, he held down guitar duties for the group until his tragic death from an accidentally self-inflicted gunshot wound in 1978.

Though his superb playing graced many tracks – notably “Introduction” and “Free Form Guitar,” both from the group’s 1969 debut, The Chicago Transit Authority – there’s no denying the power of his soloing on the group’s early hit “25 or 6 to 4.” Kath uses his wah generously to add emotion to his lines, giving them at times a frenetic despair.

Kath most likely played his Gibson SG Standard, as pictured on Chicago Transit Authority’s inner sleeve, using his favored string set, as revealed to GP: the high E string from a tenor set and a standard set for the rest, moved down one string (i.e. high E for the B string, B for the G string, and so on).

8. Lynyrd Skynyrd | “Free Bird”

GUITARIST: Allen Collins (1974)

The Bird is the word.

As it happens, the four-minute-and-24- second guitar solo that closes “Free Bird” was originally added to give singer Ronnie Van Zant a chance to rest his vocal cords during Lynyrd Skynyrd’s relentless performance schedule. At 143 bars long, the solo is far and away the most epic offering here (in fact, it’s 286 bars of recorded music because the whole thing is doubled).

The tune appeared on the group’s eponymous debut album in 1973, and guitarist Allen Collins delivered the lot on his 1964 Gibson Explorer. As Lynyrd Skynyrd’s Gary Rossington once told Guitar World, “The whole long jam was Allen Collins himself. He was bad. He was super bad! He was bad-to-the-bone bad. When we put the solo together, we liked the sound of the two guitars, and I could’ve gone out and played it with him. But the way he was doin’ it, he was just so hot! He just did it once and did it again, and it was done.”

7. Dire Straits | “Sultans Of Swing”

GUITARIST: Mark Knopfler

An understated guitar hero fingerpicks his way to glory.

Right when the world was crowning Eddie Van Halen the new King of Guitar, along came the rather unassuming Mark Knopfler – schooled in rockabilly, blues and jazz – who demonstrated that you didn’t need walls of distortion to turn heads.

Knopfler composed this pub-rock classic on a National steel guitar but thought it sounded “dull” – that is, until he picked up a Stratocaster, at which point the song “came alive.” Using nary a hint of grit on a Fender Twin, he fingerpicks not one but two standout solos.

The first features a lyrical section of elegant, Chet Atkins-style single-note and chordal bends that sigh and swoon with dreamy romanticism. In itself, that would be enough, but the outro solo is the real attention-grabber, on which Knopfler builds to a dazzling set of spitfire 16th-note arpeggios – cleanly played, precise and rousing every time you hear it.

6. The Jimi Hendrix Experience | “All Along The Watchtower”

GUITARIST: Jimi Hendrix (1968)

The greatest solo in a cover version.

This song tops any list of covers that are better than the original. Guitarists invariably refer to it as a Hendrix cover rather than a Bob Dylan original, proof of how much Hendrix made it his own. Jimi’s rhythm playing is astounding, both in the intro and in the deft chord/ melody work of the verses, and of course, there’s the small matter of four guitar solos to consider. The man many refer to as the best of all time makes the most of his Strat and Marshall rig here, but it’s his offering at the 2:20 mark that we’re interested in. Following an opening run of octaves, he gets into his stride with a typically blues-based minor pentatonic approach in C#.

At 2:32, the main solo explodes into a trademark combination of rhythm and lead, plus funky scratching on muted strings. It’s worth playing along with the scratches, trying to keep a loose wrist and consistent down-up strumming. Those few beats alone will teach you a lot about Jimi’s groove and feel.

To get the sound, select a bridge-position single-coil pickup, dial in delay at around 350ms, add compression for sustain and opt for a Vox wah pedal or something similar. You’ll hear the wind begin to howl.

5. Eagles | “Hotel California”

GUITARISTS: Don Felder & Joe Walsh (1977)

Those iconic twin-guitar harmony lines took the Eagles to new heights.

The title track from the Eagles’ fifth album, and without doubt the song the band will be most remembered for, “Hotel California” frequently tops greatest guitar solo polls. The solo begins at 4:20, forming an extended coda, over which guitarists Don Felder and Joe Walsh trade licks before joining together to play those iconic harmonized licks at 5:39.

As it turns out, those harmony lines work in a relatively simple fashion. Felder and Walsh play an arpeggio of every chord, and the harmony is created by one of the guitars always playing one note lower down in the chord. For example, the notes of the Bm chord are B, D and F#, so, if the higher guitar plays an F#, the lower guitar will play a D, and so on.

This nugget of information can take you a long way to mastering those descending arpeggios. We won’t go as far as to say you could easily work it out by ear, but if you know the chords to the song, it’s possible to jam along. And you can’t say that about many of the solos on this list!

4. Queen | “Bohemian Rhapsody”

GUITARIST: Brian May (1975)

It might just be the biggest rock song of all time.

Following Freddie Mercury’s 1991 death and a cameo moment in 1992’s Wayne’s World, “Bohemian Rhapsody” became a trigger point for a worldwide outpouring of affection and respect for Queen. Their renewed popularity would continue into the new millennium as Ben Elton’s We Will Rock You musical and the band’s discovery of a different way to exist behind frontman Adam Lambert brought their music to a new generation.

And “Bohemian Rhapsody”? Unsurprisingly, it’s Queen’s best-known song, and its brief nine-bar solo is a short and sweet musical interlude, bridging the verses to lead into what’s become known as the song’s “operatic section.” Those two words alone should warn you that this song shouldn’t work. There’s no chorus and, aside from two verses, no repetition. But of course it does work, and Brian May’s solo is the perfect melodic break.

His phrasing is loose and natural, moving across the backbeat rather than sticking to a rigidly timed grid. The fastest licks are expressive bursts, rather than repetitive noodling, and his articulate pre-bend and vibrato technique demonstrates his beautiful touch. Somehow, within the confines of the complex structure of “Bohemian Rhapsody,” this solo is made to order.

3. Led Zeppelin | “Stairway To Heaven”

GUITARIST: Jimmy Page (1971)

Heaven-sent soloing.

From the moment Jimmy Page plays the opening run on his ’59 Fender Telecaster, right through to the flurry of notes and the wailing bend that completes it, this is guitar-solo perfection – a masterpiece of composition. Rather than wander aimlessly, Page creates a song within a song.

The opening phrases set the scene, as he adds notes to the pentatonic scale to follow the song’s final chord progression. A rapid mid-solo repeating lick raises the bar before a game of question-and-answer with a haunting overdubbed guitar leads into that last flurry and bend. As we say, it’s all about the composition: licks that track the chord changes, the contour of the melody and the pacing of the widdly bits all take the listener on a journey.

Three takes were recorded (the other two allegedly still survive, presumably locked in a Led Zeppelin vault somewhere), all of them improvised, although Page has reportedly said that he had worked out the opening line. But while we’re all certainly curious to hear those solos, let’s face it: They’re not going to be any better than the one we’ve come to know and love all these years.

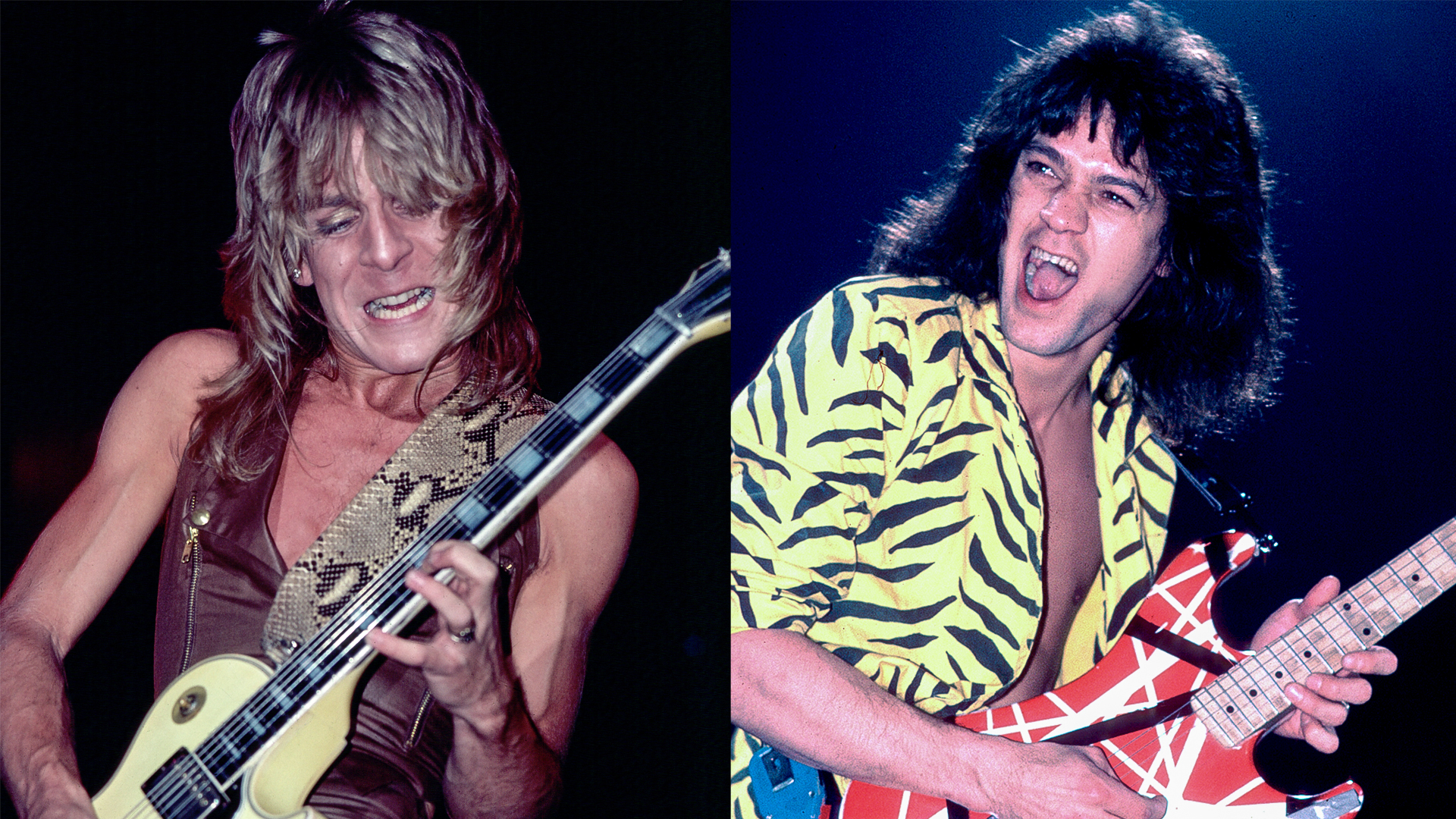

2. Van Halen | “Eruption”

GUITARIST: Eddie Van Halen (1978)

Eddie’s iconic solo that shook the world.

With its mix of fast legato hammer‑ons and pull-offs, pinched harmonics, whammy-bar dives and two-hand tapping, Eddie Van Halen’s mind-blowing instrumental guitar solo inspired a generation of guitar heroes. While the tapping gets the attention, his tone, blistering legato and creative note choices are all equally important. Amid all that virtuosity, Eddie still played with joyous rock and roll abandon.

Remarkably, Ed was never completely happy with the released recording. “I didn’t even play it right,” he told Guitar World. “There’s a mistake at the top end of it. Whenever I hear it, I always think, Man, I could’ve played it better.”

His admission aside, the track is a technical opus. The first eight bars are a bluesy affair, whose virtuoso legato licks perhaps recall the mojo of Jimmy Page’s breakdown solo in Led Zeppelin’s “Whole Lotta Love.” It’s a theme Eddie develops over the following eight bars, taking notes from the major and minor pentatonic scales to add chromatics.

His tapping finale is probably one of the least understood solo sections in rock history. Eddie’s taps are not always on the beat, which makes for tricky timing changes as he switches from tapping the first and fourth sextuplet notes to the third and sixth notes. From start to end, “Eruption” is a masterpiece that would take most guitarists a lifetime to perfect.

1. Pink Floyd | “Comfortably Numb”

GUITARIST: David Gilmour (1979)

Gilmour’s greatness comes through in waves.

In a 1992 interview with MTV’s Ray Cokes, Gilmour was asked what he thinks of Keith Richards’ theory that songs, lyrics and guitar solos are “just out there in the air and you sort of grab them.” Gilmour agreed. “I think he’s right. They sort of appear as if they are out there in the air. But I don’t know how they get there.” But the best ones he said, just happen. “The best ones do, but often you work very hard and struggle over them.”

Gilmour's two "Comfortably Numb" solos are certainly among his best, and it’s easy to understand why our readers voted his efforts to be the number-one pick in our poll. But the real question is, which of those two solos qualifies for inclusion? Whichever way you go — and granted, most fans prefer the first solo to the second — there's certainly plenty to justify the song's position at the top.

The tone is legendary. Gilmour’s signal chain consisted of his iconic black Strat, then featuring a DiMarzio FS-1 bridge pickup, into a HiWatt DR103, with the essential EHX Ram’s Head Big Muff pedal. The FS-1’s fatness and the Big Muff’s smoothness leave no hint of the harsh treble that can plague Strats. With some extra help from an MXR Dyna Comp, Gilmour had so much sustain that he could hold notes as long as he wanted. As in his live rig, he combined a WEM 4x12 cab with a Yamaha rotary speaker lower in the mix, to add subtle modulation. The epic delay was added in the mix.

The first solo, in D major, uses the Strat’s neck and bridge pickups together, permitted by a custom switching arrangement. His phrasing here is the more unconventional of the two, with arpeggios and sliding passages. Gilmour’s use of the bar for vibrato – aided by its shortened tremolo arm – again distinguishes him from typical bluesers, inspiring many a fusion player in the process. He rakes into the beginning of many of the phrases, similar to Brian May, extracting all the excitement he can from every note.

By comparison, the outro solo’s licks are more standard, with phrases similar to Hendrix’s. The passages at 4:57 and 5:12 could be from “All Along the Watchtower” or “Foxey Lady,” but in this epic track few listeners would make the connection. It sounds both masterful and improvised at the same time. Gilmour has explained he created this impression by recording five or six takes and compiling the finished solo from the best bits of each. The result is stunningly well written, with a combination of repetition and development that keeps the excitement building for two minutes. The Hendrix-style blues lick returns at 5:27, longer and more intricate than before. The aggressive double-stops first appear at 5:15, and by 5:35 he has turned that idea into a motif.

For the climax, Gilmour shoots up an octave just when it seems he’s wrung every inch of expression from his maple neck. He descends back down the neck, incorporating one of his spectacular three-fret bends on the way, and finishes with another take on that double stop motif. It has all the excitement of an improvised performance, and all the structure of a careful composition.

Both solos share brilliant rhythmic awareness. Gilmour uses triplets, sextuplets, 16th and 32nd notes freely, within the same phrase. And check out the effect at 5:10 when he plays a lick in 16th notes and then immediately repeats and expands in sextuplets. A good solo can have great tone, rhythms, melody or expression, but only a work of rare brilliance features them all to this degree.

Guitar Player is the world’s most comprehensive, trusted and insightful guitar publication for passionate guitarists and active musicians of all ages. Guitar Player magazine is published 13 times a year in print and digital formats. The magazine was established in 1967 and is the world's oldest guitar magazine. When "Guitar Player Staff" is credited as the author, it's usually because more than one author on the team has created the story.

![Gary Moore - Still Got The Blues [HD] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/8HgpUuItyZE/maxresdefault.jpg)