“I Didn’t Just Want to Be a Strummer”: How Jeff Beck Became a Guitar Hero

From Cliff Gallup to Buddy Guy, the roots of Jeff Beck’s guitar journey are planted in the fertile post-war guitar boom

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

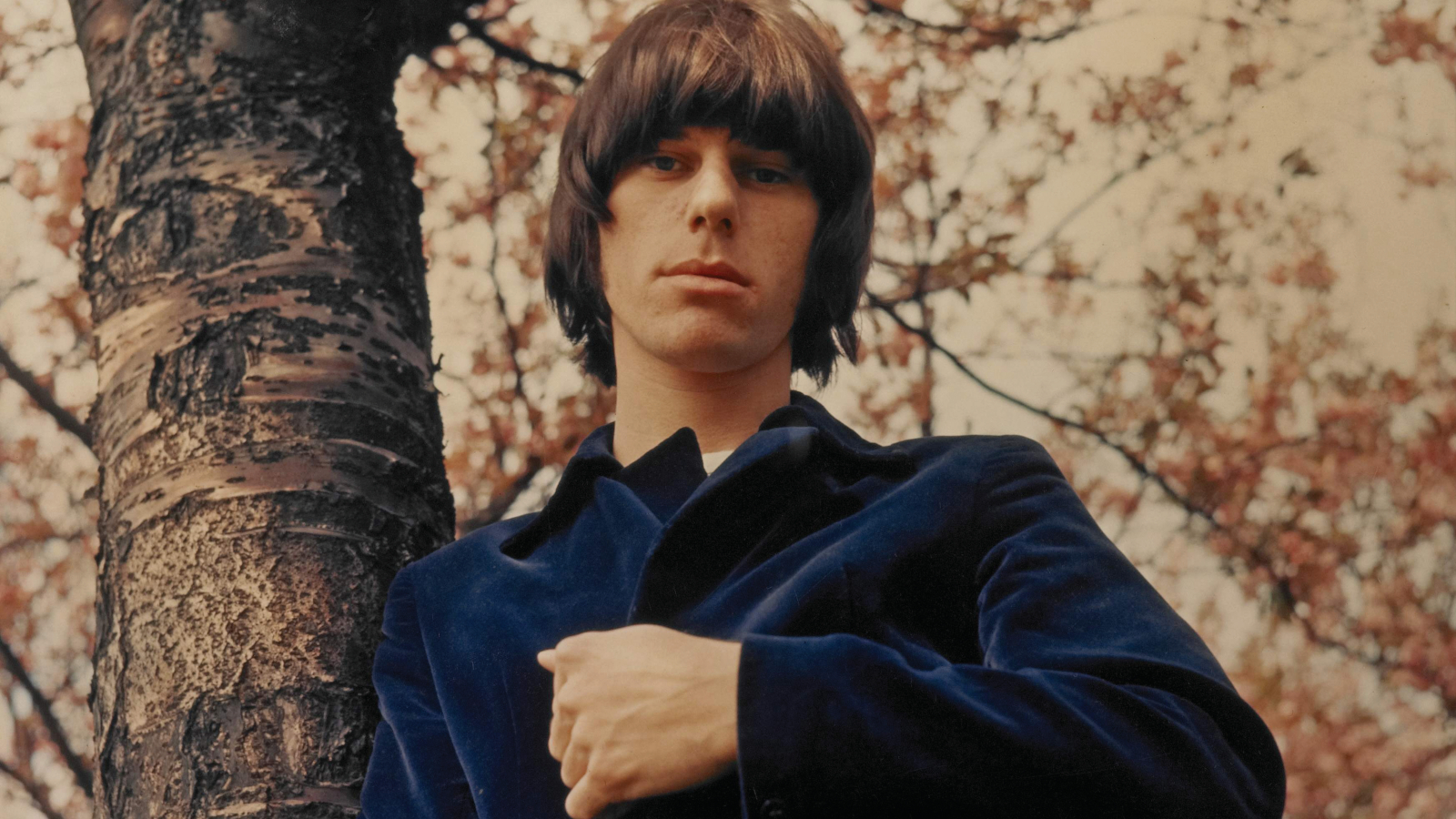

When asked in 2018 why he thought the 1960s created so many great blues guitarists – including himself, Eric Clapton and Jimmy Page – Jeff Beck had a ready response that reached high, deep and wide.

“We were down on our luck until the blues arrived,” he replied. “And it became natural music for us. We became disciples. We had to discover more. Anyone who ever had the slightest fascination with music had to find out what that sound was and where it came from. Me, Eric and Jimmy Page were stricken to the soul. We were obsessed. Thank God we were.”

For Jeff Beck, the blues was just one part of a lifelong journey that encompassed rock and roll, fusion, soul, instrumental and electronica.

The people next-door-but-one had a zither, and that was actually the first stringed instrument that I touched

Jeff Beck

Deeply curious, innately inventive, he followed his muse where it led him. The first stringed instrument to arouse his interest was the zither, as heard in the theme song for the 1949 British film noir The Third Man. Anton Karas’s haunting title composition was an international hit that year, a tune that rang in his five-year-old ears.

“The people next-door-but-one had a zither, and that was actually the first stringed instrument that I touched,” Beck revealed to Jamie Crompton in Guitarist’s 2009 cover story. “There’s a scoop for you.”

It was shortly afterward, at the age of six, that he first heard the electric guitar. Les Paul and Mary Ford’s 1951 hit “How High the Moon” was playing on the radio, and Paul’s layered guitars, slathered with slapback echo, caught his ears. “What’s that sound?” he asked his mother. “An electric guitar,” she replied. From that point on, he was all in.

Years later, “The Third Man Theme” would be the first thing Beck attempted to pick out when he played a guitar. But it took years before he actually had the instrument in his hands. “My mum wanted me to learn piano, as learning the guitar was just not done,” Beck said. “I used to spend the money for piano class on model airplanes and mark my own books to make it look like I was going to lessons.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

'The Third Man Theme' would be the first thing Beck attempted to pick out when he played a guitar

With the help of an uncle he tried his hand at violin, but his efforts were no better. “It sounded so murderous that he switched me to cello, which is an instrument that I love,” Beck revealed. “I started plucking it because I didn’t get on with bowing, and he just stopped me and said, ‘Get out.’ No patience at all.”

Beck’s fascination with guitar – like that of all guitarists born toward the end of World War II – follows the instrument’s arc in popular culture. He was born Geoffrey Arnold Beck on June 24, 1944, to Arnold and Ethel Beck. The family lived at 206 Demesne Road, Wallington, some 10 miles south of London. He had one sister, Annetta, born some four years before. Music was a big feature of their house. Ethel played piano, and her baby grand was displayed in the family’s living room. “My mum played beautifully,” Beck told Guitarist.

As he could best remember, his first experience with guitar took place around the age of 12 or 13, in 1956 or 1957. “I was at a friend’s house who was slightly spoiled,” he told Crompton. “He had a record player, a tape recorder, a guitar – all the toys.” The guitar was unloved, evident by the absence of several strings. “I started playing around with it and he said, ‘Do you wanna borrow it?’ I said, ‘Yes please!’

I remember carrying it home in the rain and taking my coat off to wrap around it to protect it. Right then, I felt a kind of protective thing towards the guitar.” With no access to guitar strings, Beck replaced the missing ones with the control-line wire from a motorized model airplane, “the kind that made the model fly round in circles,” he said.

It was the 1957 comedy musical film 'The Girl Can’t Help It' that made the strongest impression on him

While his parents tried to direct their son’s interests to Andrés Segovia and Django Reinhardt, Beck was, like most kids his age, drawn to the emerging strains of rock and roll. Between his sister’s growing record collection and the nightly pop broadcasts on Radio Luxembourg, he developed an aficionado’s appreciation for the raft of guitar players in that early rock and roll era.

But it was the 1957 comedy musical film The Girl Can’t Help It that made the strongest impression on him. The movie featured cameos by Little Richard, Eddie Cochran, Fats Domino and the Platters. But it was Gene Vincent and the Blue Caps’ mimed performance of their hit “Be-Bop-a-Lula” that most deeply affected Beck. In particular, he was taken by the playing of Vincent’s guitarist, Cliff Gallup.

Though he had left Vincent by the time the film was released, Gallup cut some 35 sides with the singer, and Beck quickly set about finding every one of them. “I knew then that I wanted to play the lead guitar breaks,” Beck said, “the fiery stuff like Cliff Gallup. I didn’t just want to be a strummer.”

While Gallup influenced his interest in the guitar as a lead instrument, Buddy Holly helped him set his eyes on owning a Fender Stratocaster. Fenders were not available in England, and Beck couldn’t have afforded one anyway. So he enlisted his neighbor, a handyman named Jack, to build him a Strat copy for five pounds. Neither Beck nor Jack knew anything about scale lengths or fret placements, which were crudely approximated.

By the middle of 1960, Beck was finally in possession of a proper guitar, a Guyatone LG-50

The results were far from perfect, but the instrument intonated well enough when capoed at the fifth fret, and Beck learned he could bend any flat notes to pitch – shades of things to come.

He had yet to pay Jack when he gave his first performance at a local youth club with another boy playing a cello as a substitute for a stand-up bass. Their appearance went over well and even got a positive mention in the local paper. But Jack was in the audience and sore about the money he was owed. “[He] made a complete twat out of me by telling everyone that I hadn’t paid him for it,” Beck recalled. “Five quid! I’d just been the belle of the ball and he said, ‘Right, I’m going to tell you all about your mate Jeff – you owe me five quid, ya cheapskate bastard!’ I thought, Right, for that, you won’t get the money!”

By the middle of 1960, Beck was finally in possession of a proper guitar, a Guyatone LG-50, and playing in his first band, having joined the Bandits, an instrumental act that was supporting Elvis Presley and Gene Vincent impersonators on a U.K. summer tour. “I was speaking to Hank Marvin about this recently and he played a similar one,” Beck told Guitarist in 2009. It had purfling around the body and a maple veneer, so it wasn’t such a bad old thing. It was about 25 pounds. Proper money when you haven’t got 25 pence!”

By this point, Beck, all of 16, had begun to attend Wimbledon College, an art school similar to those that became destinations for John Lennon, Pete Townshend, David Bowie and other musicians attempting to delay their entry into working-class society. “They had good meals” was about all Beck could say about his time there.

Beck showed up with his latest acquisition: a Burns Vibra-Artiste with a translucent cherry red finish and three Trisonic pickups

His true desire was to land a spot performing with a working band. The Deltones were a semi-pro local covers band, with players in their 20s, slightly older than Beck. He liked their sound and, as it happened, had known their guitarist Ian Duncombe, who, like Beck, was a Cliff Gallup disciple. Beck began sitting in on rehearsals and, when Duncombe announced he was leaving, asked to take his spot. An audition was arranged at which Beck showed up with his latest acquisition: a Burns Vibra-Artiste with a translucent cherry red finish and three Trisonic pickups – although Beck recalled the guitar as having “about six pickups and a hundred knobs on it. I never knew what any of them did.”

Beck won the audition, but that wasn’t enough for him. He insisted that his longtime friend John Owen accompany him on rhythm guitar. Either due to Beck’s talents or the Deltones’ lack of options, they agreed to the arrangement. As it happened, Owen had a white Fender Telecaster, and Beck managed to convince him to swap, as the Tele would be a more appropriate lead instrument. It worked, for a time, but when Owen reclaimed the guitar, Beck was stuck again with his Burns.

But with Fender guitars now available in England, he set his sights on owning one. “Me and a friend got a train and a bus up to London from Croydon and we asked a porter where all the guitars were,” he recalled.

After a while we went in, and I said, ‘I’d like to try the Fender Stratocaster please,’

Jeff Beck

“He happened to know and said Charing Cross Road, so we jumped on a bus, ran upstairs and looked out the window for guitar stores. My mate suddenly said, ‘Oh my God!’ We belted down the stairs, stumbling over one another, ran in front of all the traffic and there we found a Tele and a Strat in the window of Jennings Musical Instruments,” he said, referring to the original Vox Amplifier Shop, at 100 Charing Cross Road. “We stood there motionless, salivating, for at least five minutes and my mate said, ‘Shall we go in?’ I said, ‘No, no we can’t go in!’ We were completely freaked out.

“After a while we went in, and I said, ‘I’d like to try the Fender Stratocaster please,’ and the guy said, ‘Yes gentlemen, certainly, sir, you are intending to buy it, are you?’ We didn’t have a pot to piss in but we said, ‘Yeah, yeah.’

“Another shop in Charing Cross Road we used to bug was called Lew Davis. There we discovered a slap-back echo device” – most likely a Binson Echorec – “and we were in heaven. We made friends with a sales guy who used to let us play any guitar in the shop. He was great, he’d leave us alone and say, ‘Just don’t nick anything! We never did, and they couldn’t get rid of us.’ Then some 15-year-old kid would come in and his dad would buy him a Strat outright for cash. Case and all! Strap, strings, pick… We’d sit there scowling.”

Determined to get a Strat for himself, Beck appealed to his mother for the £147 required. She agreed to pay a deposit, allowing him to take possession of the instrument on credit. Now duly in debt, Beck quit art school to become a full-time working musician.

Determined to get a Strat for himself, Beck appealed to his mother for the £147 required

On May 22, 1961, he left Wimbledon College just in time for the Deltones to splinter. He briefly worked with Gene Vincent imitator Gordon Paterson, who performed under the nom de plume Cal Danger, and joined Deltones singer Johnny Del in his new group, the Crescents. But musically he was rudderless.

He found a direction in 1963 courtesy of a friend, Ian Stewart. A pianist, Stewart was a founding member of the Rolling Stones, who had become stars of London’s Marquee Club, in Oxford Street. Since 1962, the venue had been the home of Blues Incorporated, the seminal blues act founded by Alexis Korner and Cyril Davies, who brought the songs and sounds of the Mississippi Delta to England.

Stewart loaned Beck a cartload of blues albums, including Folk Festival of the Blues, a compendium of Chicago’s electric blues scene that featured key figures like Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Sonny Boy Williamson and Buddy Guy. “I just wore out the album,” Beck said. He was particularly moved by Guy’s prowess on his Fender Strat. “It was total manic abandon that broke all the boundaries. Long, developing solos, just the opposite of all the pop stuff at the time.”

As he’d done with Cliff Gallup, Beck made exhaustive work studying the electric blues guitar greats, developing new skills and techniques. He put together the Nightshift, a blues act that played some of the music’s hot spots, including Eel Pie Island – a former trad-jazz spot that had shifted its musical affiliation with the emerging blues boom – and was even contacted by John Mayall as he was putting together the Bluesbreakers. In the end, Beck ended up with the Tridents, a blues act led by brothers John and Paul Lucas and which the Nightshift had supported at Eel Pie Island.

There wasn’t an ounce of musical sense to it, but they loved it because it was different

Jeff Beck

As a document of this period, the Tridents’ 1964 live Eel Pie recording of “Nursery Rhyme,” from the 1991 Beckology compilation, reveals the guitarist’s gifts with hammer-ons and pull-offs, trills,

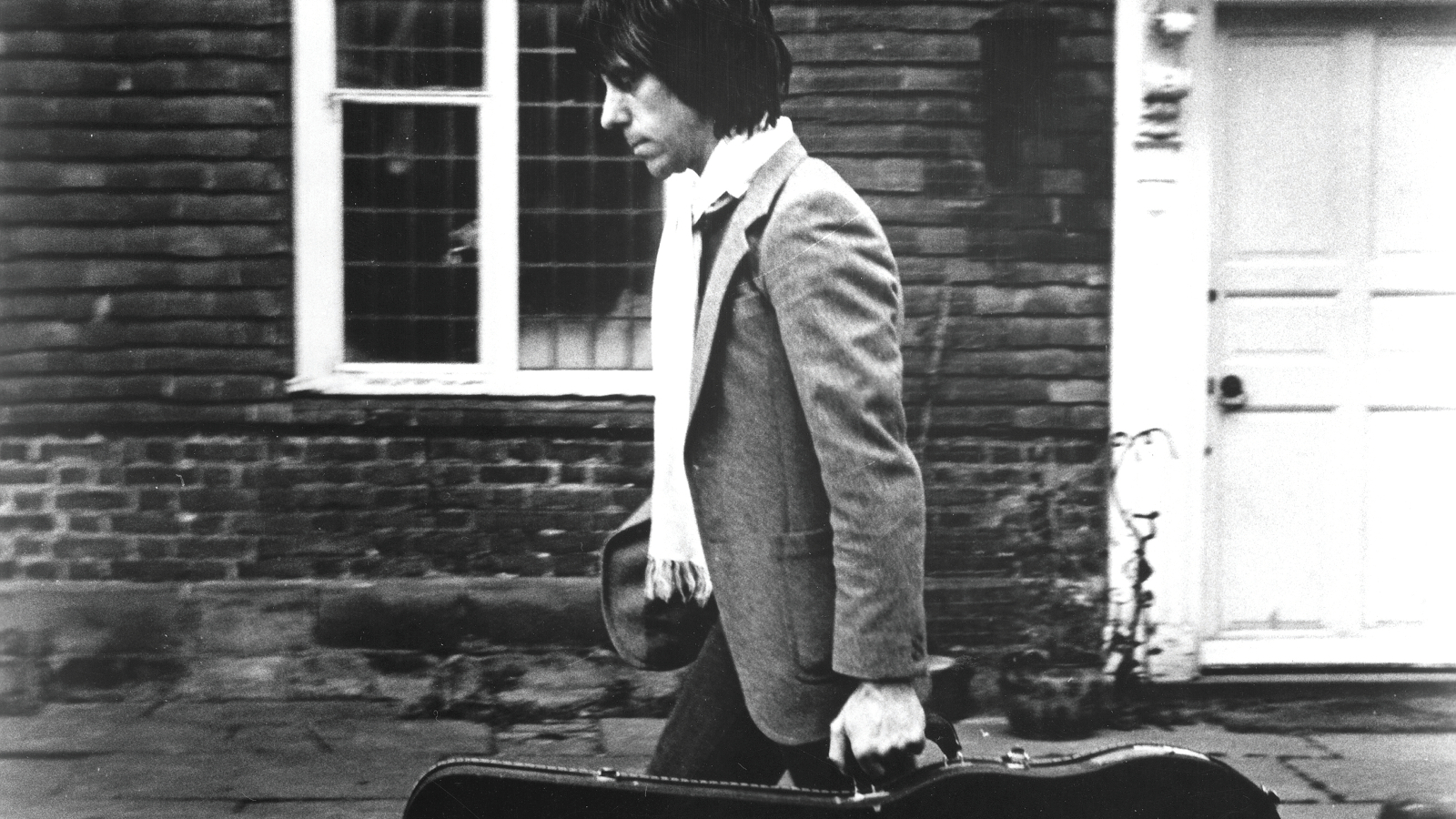

It was September 1964, and it’s here that Jeff Beck the guitar hero begins to emerge. By this point he was playing a white Fender Telecaster through a Vox AC30 Top Boost, supplemented by a Binson Echorec, which he used to create spontaneous freak-outs, as well as an early homemade fuzz box.

“There wasn’t an ounce of musical sense to it,” he said in the liner notes, “but they loved it because it was different.”

It was a lesson that would serve him well for years to come.

Christopher Scapelliti is editor-in-chief of GuitarPlayer.com and the former editor of Guitar Player, the world’s longest-running guitar magazine, founded in 1967. In his extensive career, he has authored in-depth interviews with such guitarists as Pete Townshend, Slash, Billy Corgan, Jack White, Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren, and audio professionals including Beatles engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott. He is the co-author of Guitar Aficionado: The Collections: The Most Famous, Rare, and Valuable Guitars in the World, a founding editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine, and a former editor with Guitar World, Guitar for the Practicing Musician and Maximum Guitar. Apart from guitars, he maintains a collection of more than 30 vintage analog synthesizers.