"I Was Set Free": Humble Pie Guitarist Clem Clempson Talks Lighting up One of the 1970s’ Hottest Rock Albums: ‘Smokin’’

How Humble Pie was reignited after Peter Frampton's sudden departure

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

After several well-received U.S. tours, a striking self-titled A&M debut in 1970 and the critically acclaimed Rock On album in early 1971, British quartet Humble Pie were still largely an opening band in the U.S., with only a relatively modest following back in their native England in fall 1971.

Still, expectations – and record company advances – were high. But despite being among the first bands ever dubbed a “supergroup” by the British press – owing to a lineup that included both the great singer/guitarist Steve Marriott of the Small Faces and a young phenom guitarist named Peter Frampton from a band called the Herd – Humble Pie were commercial underachievers.

That all changed with a concert they recorded with engineer Eddie Kramer at the Fillmore East in New York City.

Article continues belowThe resulting album, 1971’s Performance: Rockin’ the Fillmore – with its titanic highlights, including the proto-punk of “I Don’t Need No Doctor” and the OG stoner anthem “Stone Cold Fever” – catapulted Humble Pie into what the band’s friend David Gilmour once described as “the superleagues.”

Lengthy cuts like “Four-Day Creep” and a cover of Ray Charles’ “Hallelujah I Love Her So” featured Frampton’s flights of futuristic modal-blues soloing, Marriott’s braying, stratospheric voice, and the R&B-informed rock rhythm section of drummer Jerry Shirley and ex-Spooky Tooth bassist Greg Ridley.

Performance: Rockin’ the Fillmore was quickly certified Gold and acted as an instant coronation. Then came the beheading. Before Performance was even released, Frampton quit the band to pursue a solo career.

It was rather sudden, but very welcome... the last few months of Colosseum had been somewhat frustrating and sort of restrictive for me

Clem Clempson

Meanwhile, guitarist David “Clem” Clempson, who already had an enviable career under his belt with the brash, youthful British blues-rock band Bakerloo, was having doubts about his current band, British jazz-rock juggernaut Colosseum, an artful and innovative quintet that featured notable names like singer Chris Farlowe, drummer Jon Hiseman, bassist Mark Clarke and a gifted saxophone player (soon to be a prog legend) with the rather Dickensian name of Dick Heckstall-Smith.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

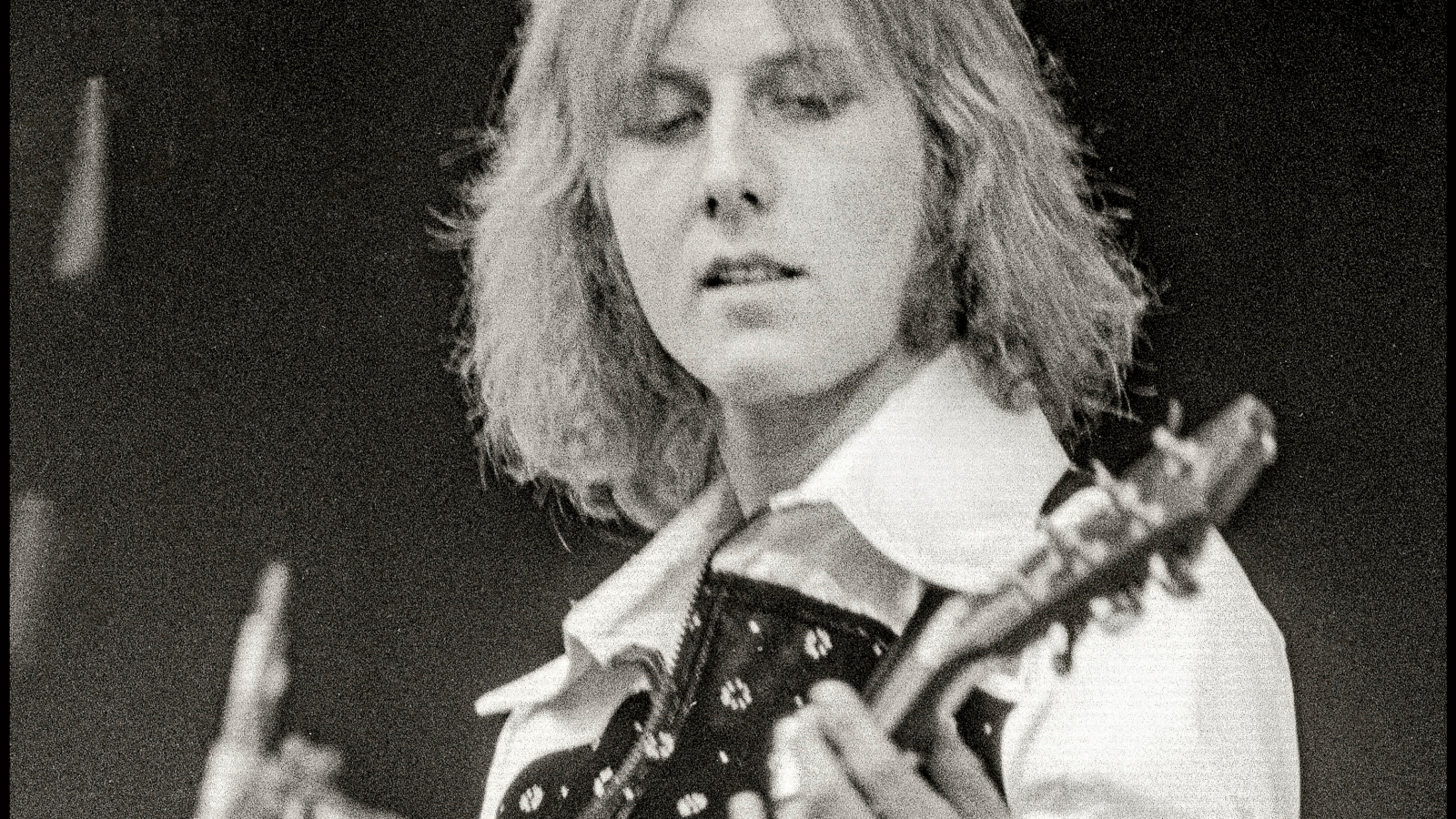

Receiving a call from Steve Marriott to “come down to Olympic Studios and audition for the band,” Clempson arrived only to find himself at a full-on press conference to announce that he would be joining Humble Pie as their new lead guitarist.

“It was rather sudden, but very welcome,” Clempson, now 73, says with a laugh. Although he would later continue to work with Colosseum, as well as with Jack Bruce, B.B. King, Jeff Beck, Andrew Lloyd-Webber and others, “the last few months of Colosseum had been somewhat frustrating and sort of restrictive for me,” he says.

“We would work for literally days on just a vocal harmony part, or a particular unison line. It got to a point where I really couldn’t take it anymore. So when I got the call from Steve Marriott to audition for Humble Pie, I was quite eager.

“That was the most refreshing thing about Humble Pie, that it was all so much more immediate. I was set free in a way. I could finally just wail. And that’s all I wanted to do!”

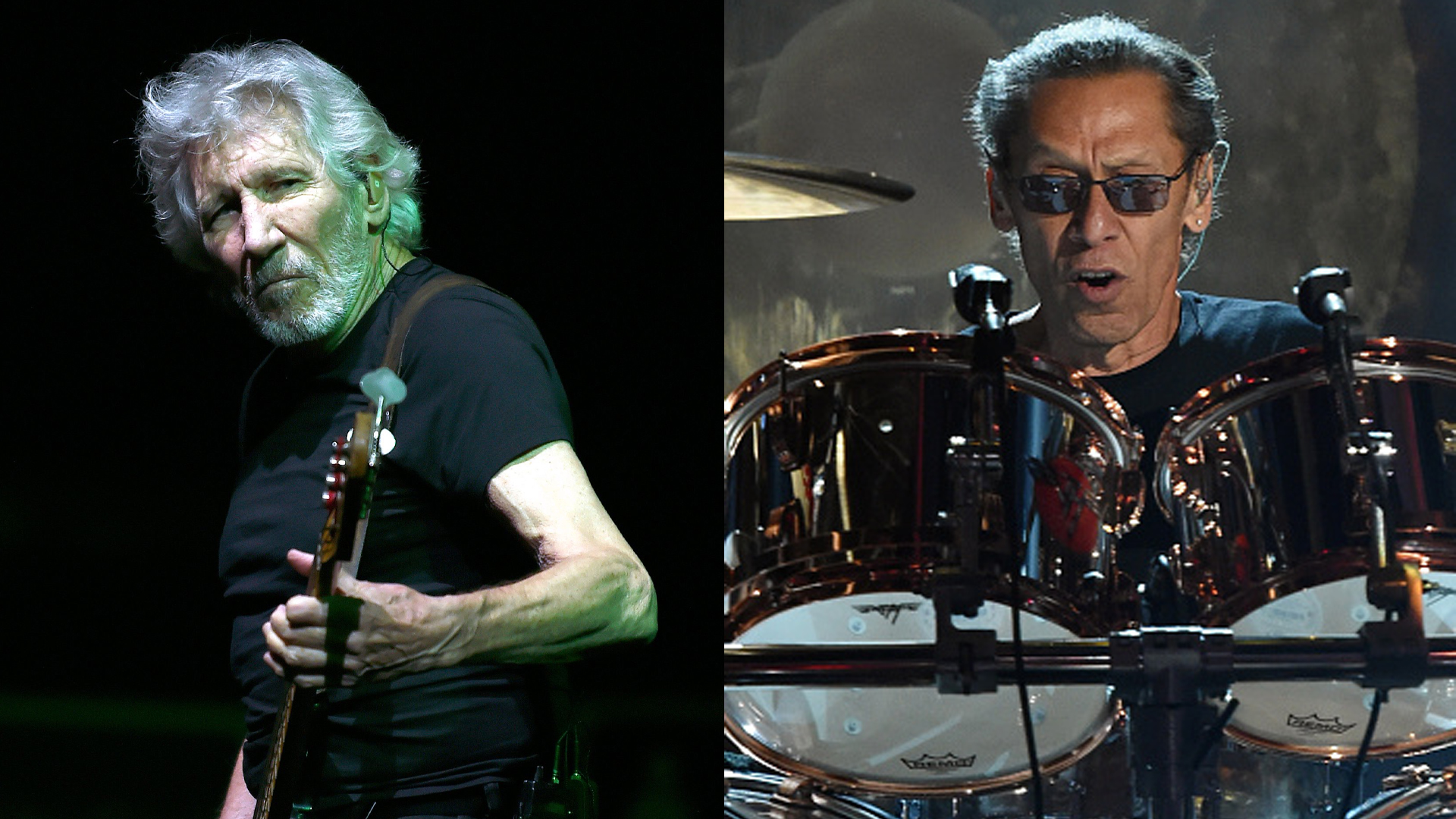

Clempson’s approach to the guitar had an immediate and significant effect on Humble Pie’s music. “We didn’t see Peter quitting the band coming at all,” Jerry Shirley recalls. “But after Peter left, Humble Pie made a conscious decision to sort of rein in the longer solos, partly because that was very much Peter’s signature. So mostly the live solos became much more compact.”

After Peter [Frampton] left, Humble Pie made a conscious decision to sort of rein in the longer solos

Jerry Shirley

The main difference between Frampton’s and Clempson’s styles, Shirley says, is that “Peter leaned a bit toward chromaticism, because of his jazz background, and Clem leaned more toward the blues vocabulary. But they’re very similar in that they’re both such devoted players. The guitar is everything to both of them.”

“Peter obviously loved Wes Montgomery and Kenny Burrell, and players like that,” Clempson notes, “but still, I always figured he learned like I did, like we all did back then: by copying the things that he liked and absorbing those into his own choices.

“I think Peter just finds nice notes to play over any given chord that he’s playing over, though his note choices are slightly different from the sorts of things that I like to do. I never actually learned the major or minor pentatonic scale on guitar.

“This is partly due to the fact that I’d already had a whole education in classical piano. So when I took up the guitar, I knew all my scales and chords on the piano, and I just sort of discovered where those same notes and chords were on the fretboard, but without ever even looking at a scale diagram or anything like that.

“I learned the chord shapes, of course, but it was years before I ever practiced a scale or an arpeggio.”

Jumping straight into Olympic Studios’ Studio One, the revitalized quartet quickly knocked out Fillmore’s funky and fantastic follow-up – and eventually the band’s biggest-selling album: 1972’s Smokin’, which, 50 years on, forms the thematic centerpiece of the just-released, freshly remastered, and royally rocking eight-CD collection Humble Pie: The A&M 1970–1975 Limited Edition Boxset.

There was never more than one or two takes of anything

Alan O’Duffy, producer

The long-player was recorded and mixed by lauded producer Alan O’Duffy, who’d just stunned the world of both rock and musical theater with his pioneering work on the Jesus Christ Superstar cast album.

“Humble Pie was so competent and powerful at that time,” recalls O’Duffy, who enjoyed the able engineering assistance of the late Keith Harwood, of Led Zeppelin, Bowie and Rolling Stones fame.

“There was never more than one or two takes of anything. There was never that thing of, ‘I want to replace my guitar part,’ or ‘I didn’t like the hi-hat feel on that. Can I replace the hi-hat?’ It was just knock it out, no bullshit, end of story.”

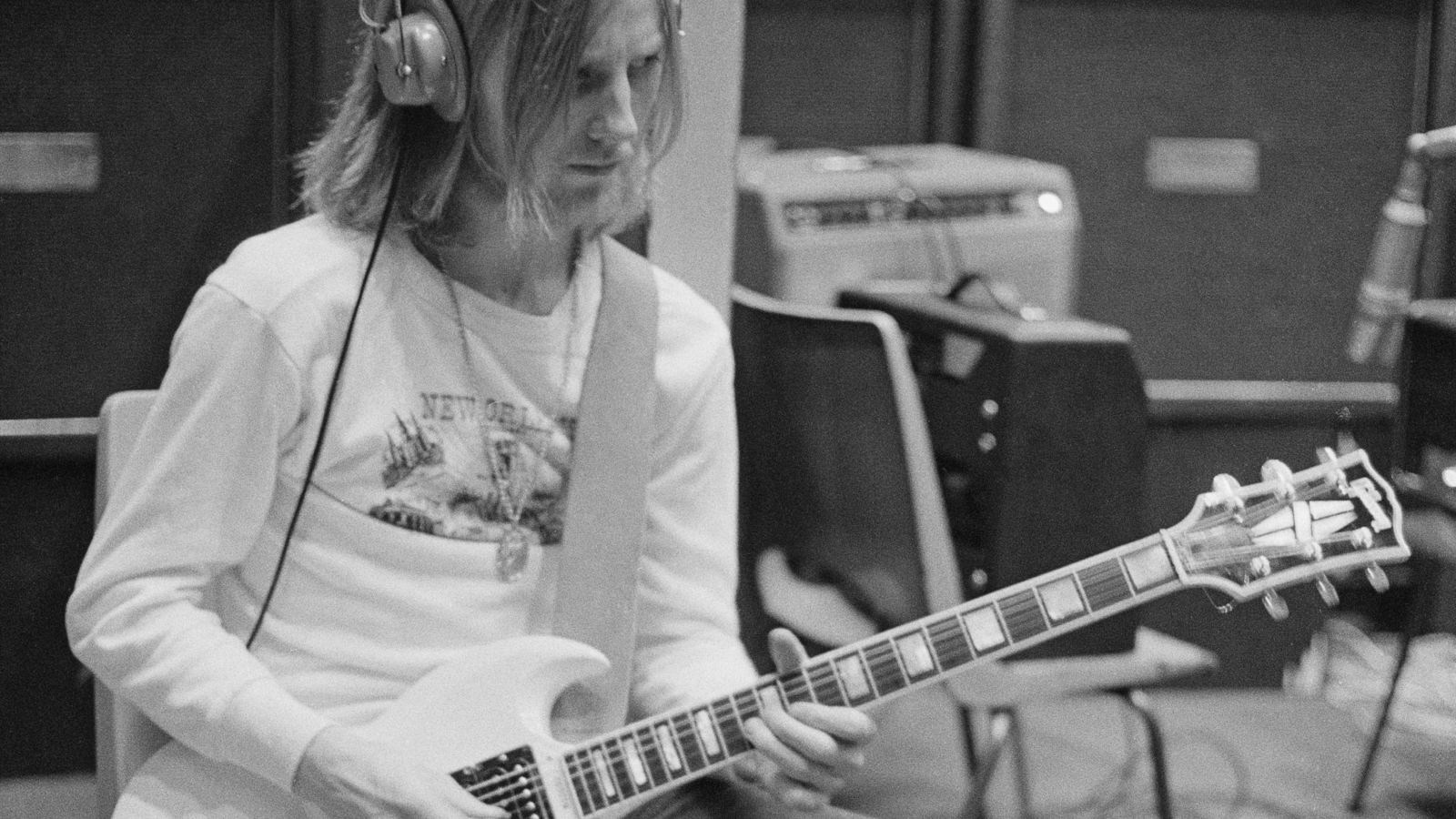

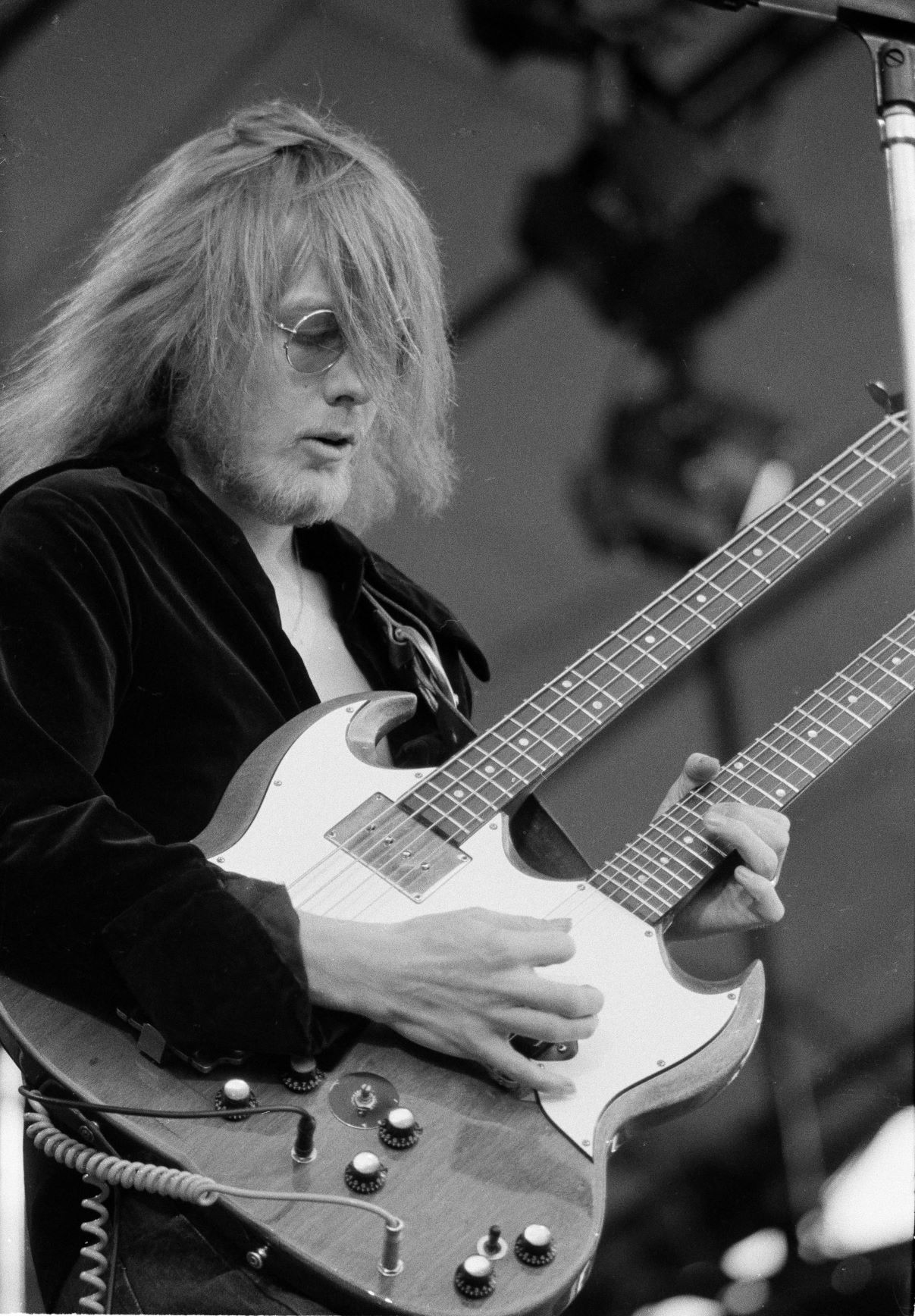

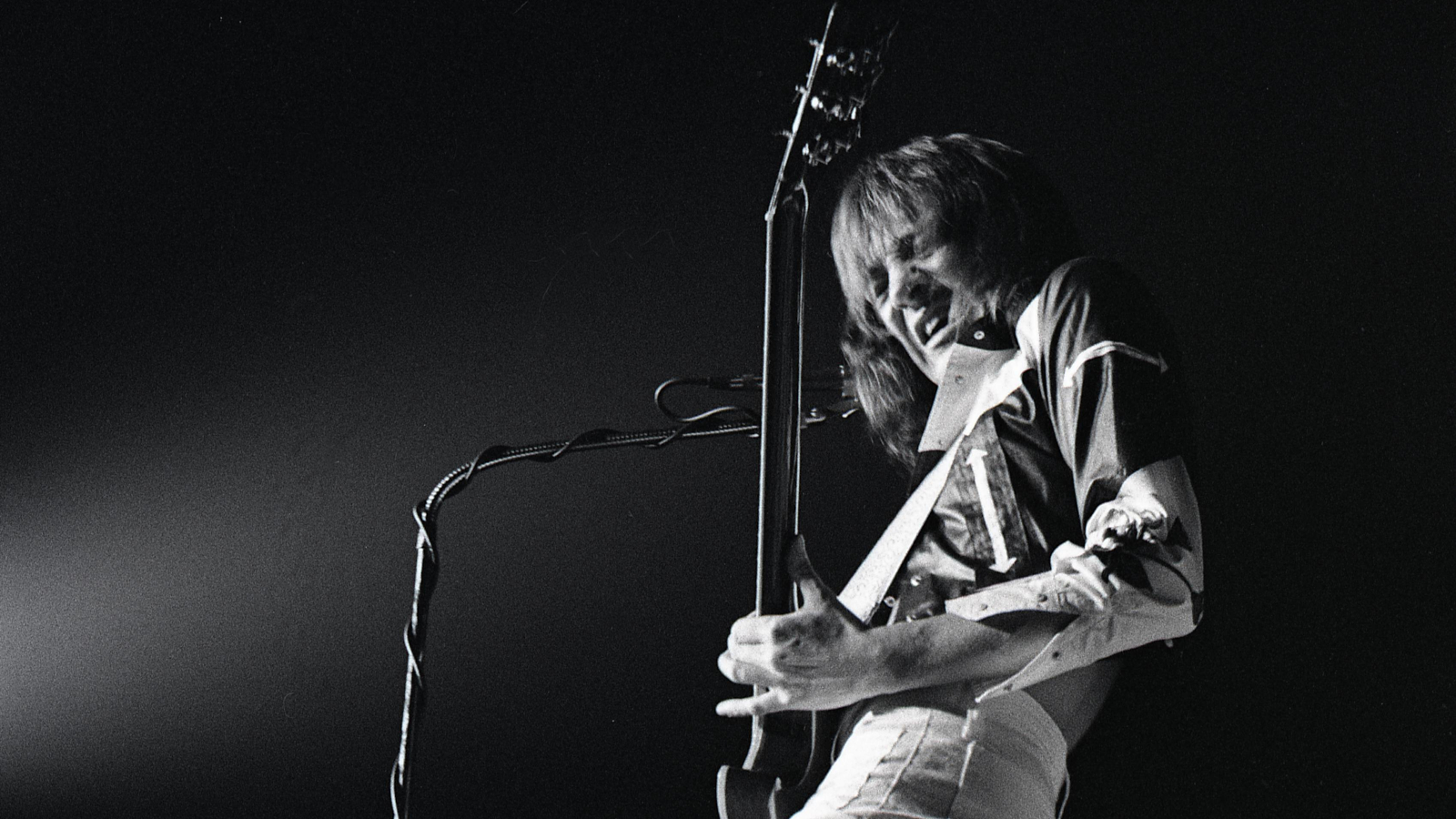

From the first session, the band’s fresh alchemy completely clicked. Performed with a white, three-pickup Gibson SG Custom and his favorite 1958 Gibson Les Paul goldtop, Clempson’s wicked wah-wah tones and adroitly musical, progressive blues filigrees and solos slotted in perfectly with multitasker Marriott’s dynamic Hammond organ chords, rocking Epiphone Dwight and Coronet rhythms, and sky-searing vocal bursts.

With the more stripped-down Ridley/Shirley rhythm axis heating up the grooves, tracks like “Hot & Nasty,” “The Fixer” and the perennial “30 Days in the Hole” still positively smoke with a pungent whiff of the fiery, fun, funky fumes emanating from Olympic’s storied tracking room.

“The great thing for me, as well, is that no one ever suggested anything about what I should play,” Clempson remembers. “When I came into the band, they were already rehearsing quite a bit of the new material – all the things that would end up on Smokin’, like ‘The Fixer,’ ‘30 Days in the Hole,’ ‘Sweet Peace and Time,’ ‘C’mon Everybody’ – all these great riffs and ideas, with an eye to getting into the studio as soon as possible to record them.

No one ever suggested anything about what I should play

Clem Clempson

“So all I really had to do was to find parts that would fit well over what they were already doing. Sometimes I’d play the main riff in unison with Steve; other times I’d play a harmony part, or take a lead.

“When it came time to tour and approach the material they had already done – the fan favorites like ‘I Don’t Need No Doctor’ and ‘Four-Day Creep,’ – I approached them in the same way: try to understand what Steve was doing with the riffs and lines, and decide what I’d like to do over it.

“Now, I had, of course, heard the Rockin’ the Fillmore album, and I knew there were certain things I should definitely nail as is – Peter’s harmony line over the opening riff to ‘Four-Day Creep,’ for instance. I had to do that verbatim, of course.

“In fact, there were plenty of Pete’s great lines and parts that I wanted to cop. But when it came to the soloing and improvised parts, I just wanted to do it my way, which felt more honest.”

As O’Duffy recalls, the band set up in Olympic’s Studio One main room very close together, with only four-foot-high baffles to separate their equipment. “Basically, Jerry’s drums were in the middle of the floor, and then Greg Ridley’s bass amps would be to the right and nearest to the drums.

“There’d be Clem on the right, and Steve on the left. The guys would all have headphones on, and Steve would maybe have a mic if he wanted to do some scratch vocals. And while we did use baffles, we didn’t get too hung up about a bit of bleed. A bit of Clem’s guitar in the drum mics? Big deal.”

None of those solos were more than two takes

Clem Clempson

O’Duffy – who when mixing panned Clempson’s Marshall JMP Super Lead 100 to the right and Marriott’s Marshall JMP Super PA 100-watt tube amps to the left – recalls using Neumann KM56 and AKG C451 mics on Clempson’s Marshall cabs, with an attenuation of about -20dB, as the amps were run “quite hot.”

“None of those solos were more than two takes,” Clempson says. “I especially remember the recording of ‘Hot & Nasty.’ That was just such a special evening. We started with this jam, just having fun, but it had a great groove.

“We played it through, and then Steve knocked out a few lyrics and put a vocal on it. Done. But then Stephen Stills suddenly appeared from nowhere and came up with this great backing vocal line to put over it: ‘Do you get the message?’ He said, ‘Do you mind if I put it on the track?’ So off he went to the live room and put that down, and it was amazing.

“This is what being in the studio is supposed to be like, really,” Clempson continues. “And it led to one of the best recordings I’ve ever been a part of. That’s as good an example of the camaraderie in the band as anything I can think of.

“We were very close then, having a lot of fun, really giving it one, and I think that really comes through on the record. We weren’t trying to conquer the world or anything. It was just about the joy of doing it.

“Look, it’s a well-known story how things started to go downhill after a while, but for those first 18 months or so that I was in the band, we loved being together, and there was such a great feeling among us all.

We were very close then, having a lot of fun, really giving it one, and I think that really comes through on the record

Clem Clempson

“I suppose that’s the most heartbreaking thing about what happened later: knowing what we’d lost.”

While both Clempson’s and Marriott’s interlocking leads are utterly wicked throughout, the jagged, righteous rhythms on album tracks like “Road Runner’s ‘G’ Jam” and “Sweet Peace and Time” equally run the show – big, fat Marshall tones that burst with mojo.

“My rhythm playing improved quite a lot by joining Humble Pie and working with Steve,” Clempson maintains. “He was an absolutely fantastic rhythm player. Even apart from his big power chords, which were magnificent, even playing a Strat through a clean amp, he would find so many lovely little licks.

“One Humble Pie song I enjoy listening back to is ‘Black Coffee’ [from 1973’s Eat It, the follow-up to Smokin’].

"I’m playing that sort of boogie figure on the bottom two strings, and the slide guitar as well, but Steve came up with these little clean soul music licks over that on the top three strings that are just so tasteful and have so much personality.”

Marriott, as Jerry Shirley explains, continued to be an ardent student of the guitar throughout his life, which was cut short in 1991 in a tragic house fire. (Watch this stunning version of “Five Long Years” for a taste of his Chicago Blues prowess.)

“There was this fascinating guy out of Chicago,” Shirley explains, “an amazing artist and a guitar player named Bob Novak. They called him Bumble Bee Bob. [Novak died in 2015 at the age of 83.] Bob had learned blues guitar and harmonica straight from a lot of the great bluesmen in Chicago – Otis Rush, Albert King, Muddy Waters… guys like that.

“He knew exactly how they played all those licks. He was a friend of the band from the very early days, and he used to come over to England and stay with Steve for weeks at a time, and the two of them would sit down with their guitars and Bob would show Steve exactly how those guys fretted and nuanced all those licks.

“Steve was in awe of Bob, and as Steve already had great vibrato and was a great player to begin with, it took his playing to a whole new level. And this was eight years after Humble Pie.”

Steve [Marriott] turned me on to so much music that I never knew existed

Clem Clempson

Marriott’s influence on Clempson didn’t stop with blues-and-rhythm licks. “Steve turned me on to so much music that I never knew existed, like the Staples Singers,” Clempson says. “Ever since I met him, Mavis Staples has been my all-time favorite female singer.

“And when he turned me on to [acoustic guitar giant] Leo Kottke, I thought, How can one person possibly be doing all that? Because of him, I had to buy a Martin and begin learning how to fingerpick properly.”

Likewise, it was when Marriott asked Clempson to play slide on Smokin’ that bottleneck became an integral part of his palette.

“All these things are what allowed me to have a really successful career in the session world when I decided I didn’t want to be on the road quite so much anymore,” Clempson insists. “I had built quite an extensive vocabulary by then, and a lot of that came from joining Humble Pie.”

In fact, if there’s any advice Clempson says he would offer to young players who want to improve their vocabularies and up their game, it’s that same open-minded approach.

“Explore more styles of music than just the one you mostly gravitate to, and do more than just play solos,” he stresses. “Early on, I missed out on a lot of great rhythm playing that I didn’t ever think to listen to carefully.

Explore more styles of music than just the one you mostly gravitate to, and do more than just play solos

Clem Clempson

“I only wanted to listen to B.B. King, Buddy Guy, Jeff Beck and Peter Green. I wanted to hear the great soloists, and that’s what I wanted to do myself. Sure, I was aware of people like [Howlin’ Wolf ’s] Hubert Sumlin, but I never really took close notice of exactly what he was doing.

“If I listened to a Buddy Guy record, I’d really only focus on the lead guitar and not on the rest of the instruments, especially the rhythm players. Go listen to all those fantastic Tamla/Motown rhythm guitarists, for example. How the hell did I not notice how great that was?”

Listening back to Smokin’ after 50 years, engineer/mixer O’Duffy knows exactly how great Humble Pie were, and he’s not afraid to put a bow on it. “The Humble Pie guys were the genuine article,” he says.

“Humble Pie were playing with their hearts. They weren’t playing ‘Let’s pretend we’re a rock band’ or ‘Let’s pretend we’re a soul band.’ There are other bands that I can name who would’ve been equally clever playing a bossa nova or a samba or a pop record. Humble Pie were playing the thing itself, not a version of that thing.

“I feel privileged to have lived at a time when these people were on earth and were in our circle, and we had the pleasure of working together and making something truly beautiful.

“I’m still proud. It’s 50 years ago, and I’m a proud man listening back to ‘The Fixer’ and ‘Hot N’ Nasty’ and ‘Sweet Peace and Time.’ It all still sounds spectacular.”

Browse the Humble Pie catalog here.

A former editor at Guitar Player and Guitar World, and an ex-member of Humble Pie, Mr. Bungle and French band AIR, author James Volpe Rotondi plays guitar for the acclaimed Led Zeppelin tribute, ZOSO, which The L.A. Times has called “head and shoulders above all other Led Zeppelin tribute bands.” Find JVR on Instagram at @james.volpe.rotondi, on the web at JVRonGTR.com, and look for upcoming tour dates at zosoontour.com