Celebrating 50 Years of Humble Pie’s ’Performance: Rockin’ the Fillmore’

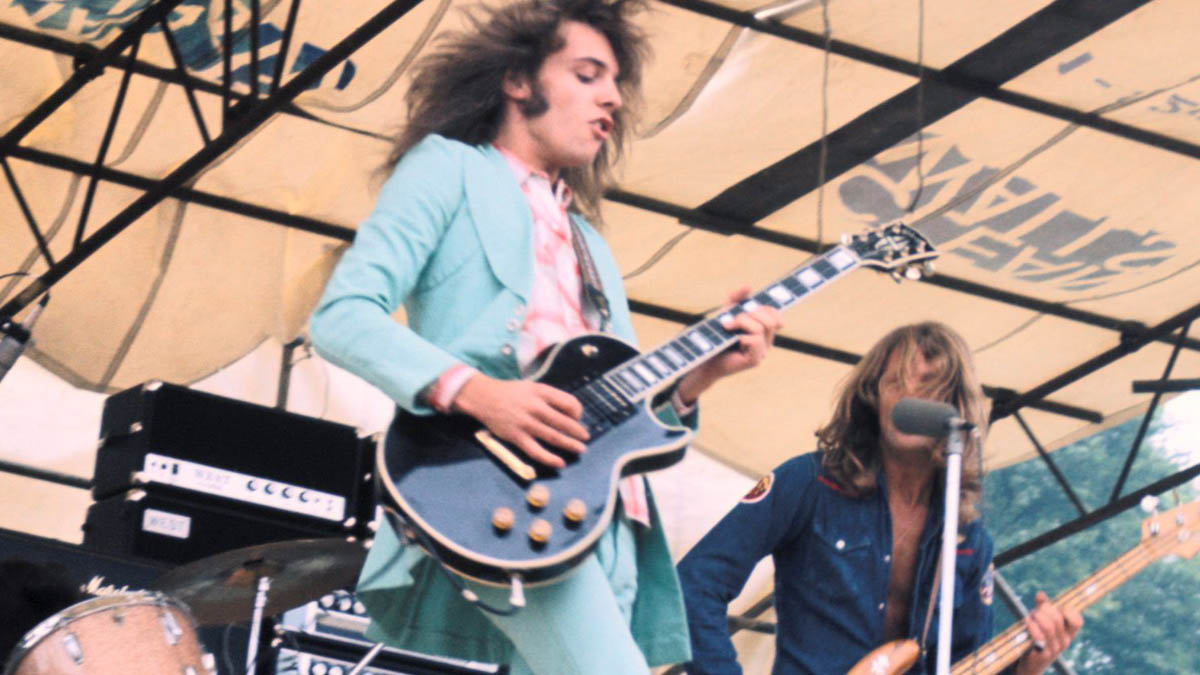

Peter Frampton's last act on record with the band set a new standard for the live rock album.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Peter Frampton's final recording with Humble Pie was, by some irony, the band’s most successful, and is widely acknowledged as one of the most influential live albums of the decade.

Culled from four sets recorded on May 28 and 29, 1971, at New York City’s Fillmore East, Performance: Rockin’ the Fillmore was released that November as a double-album set. Humble Pie were second on the bill, after Fanny and before headliner Lee Michaels, a fact hardly anyone seems to remember, so great was the album’s impact on rock history.

Among the artists who have felt its influence were the Van Halen brothers, Aerosmith, Kiss, Quiet Riot, Skid Row, and other acts ranging from Tesla to the Black Crowes to Rival Sons, and beyond.

There were several reasons for that explosive impact: the lengthy but gripping improvs, the deep fatback grooves and monster fills by drummer Jerry Shirley and bassist Greg Ridley, the outrageous charisma of the late singer and rhythm guitarist Steve Marriott, and, surely, the massive guitar orchestra pouring out of Frampton and Marriott’s 4x12 cabs, a sound which presaged the so-called “brown” sound by a good seven years.

“So many players have asked me what the setup was for those performances,” Frampton says, “and I have to tell you, it was so simple. It was just a 100-watt Marshall plugged into a 4x12 Marshall slant cabinet, and a 50-watt Marshall into a 4x12 slant cabinet, with the two amps connected together. And I plugged my Les Paul Custom into that.

“That’s it. That’s all there was. I used my volume pot on my guitar to turn down during the vocal parts, and I knew that my max throw on it was solo level. No echo, no delay, no boost. If there was any reverb or delay effect to speak of, it was just the amazing acoustics in the old Fillmore East.”

Indeed, that natural crowd and room ambiance – picked up wisely by engineer Eddie Kramer on left, center, and right room mics – is one big reason why so many classic live albums were recorded there, including Jimi Hendrix’s Band of Gypsys and the Allman Brothers' At Fillmore East, among others.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

And Frampton is not the only guitarist on the album with a stupendous sound. Marriott’s single-pickup Epiphone Coronet, strung impossibly with .012s and driving a Marshall amp rig nearly identical to Frampton’s, positively roars. And even given Frampton’s quicksilver modal runs, it’s Marriott’s stinging Chicago blues licks, which he liberally injects into his raucous, sing-rapping stage banter, that very nearly steal the show.

“I was a huge admirer of Steve’s playing from the first time I saw him play with the Small Faces,” Frampton says. “He’s always voted right up there as one of the all-time greatest voices, but he’s sorely underrated as a guitar player.”

Indeed. Listen to the nearly 30-minute version of Dr. John’s “I Walk on Gilded Splinters,” or the epic prog-blues of “Rollin’ Stone,” and you’ll hear two guitarists working in uncanny tandem, even as Frampton blends dorian/blues licks (“I Don’t Need No Doctor”), Aeolian runs (“Stone Cold Fever”), and Mixolydian lines (“I’m Ready”), along with crisp arpeggios and swinging major and minor pentatonic licks (“Hallelujah, I Love Her So”).

Meanwhile, Marriott charges at ferocious five chords, swooping minor-to-major-third blues hammers and trills, and savvy minor-seventh chord comping.

The alchemy between the two players on Fillmore created a new paradigm for rock guitar, one where jazz modality and blues grit could combine for blissful moments of twin-guitar harmony, flashes of surprising counterpoint, and even stark contrast.

“Steve was great at working out double solos with me,” echoes Frampton, “until we’d really sound like one big guitar. I just learned so much from Steve’s attack and his conviction on the instrument.”

A former editor at Guitar Player and Guitar World, and an ex-member of Humble Pie, Mr. Bungle and French band AIR, author James Volpe Rotondi plays guitar for the acclaimed Led Zeppelin tribute, ZOSO, which The L.A. Times has called “head and shoulders above all other Led Zeppelin tribute bands.” Find JVR on Instagram at @james.volpe.rotondi, on the web at JVRonGTR.com, and look for upcoming tour dates at zosoontour.com