Peter Frampton on the Joy of Guitar Playing, Developing His Style, and Recording With George Harrison

On 'Frampton Forgets the Words,' the rock icon lets his Les Paul do the talking.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In 2006, Peter Frampton’s keen desire to shine the primary spotlight on his guitar playing – and perhaps to put to rest the teen-idol stigma that had frustrated him since his 1976 blockbuster, Frampton Comes Alive! – was reciprocated with a Grammy Award for Best Instrumental Pop Performance.

The album was Fingerprints, a 14-track guitar tour de force that featured cool covers of songs like Soundgarden’s “Black Hole Sun,” along with funky, accomplished originals and guest appearances from Hank Marvin, Warren Haynes, Mike McCready, John Jorgenson, and a reunited Bill Wyman and Charlie Watts.

In the years since, Frampton has cut a slew of solid albums that speak to his legacy as both a pivotal jazz-inspired rock player who bucked the British blues boom and an open-minded elder statesman, as likely to champion Radiohead and Pearl Jam as Wes Montgomery and Kenny Burrell.

Indeed, it’s Radiohead’s thorny and lurching “Reckoner” that acts as the lead-off track on the Peter Frampton Band’s latest album, the instrumental covers collection aptly titled Frampton Forgets the Words.

Frampton and his band – keyboardist Rob Arthur, bassist Steve Mackey, guitarist Adam Lester, and drummer Dan Wojciechowski – perform a spectrum of his favorite soul and rock tunes, ranging from Sly & the Family Stone’s “If You Want Me to Stay” and George Harrison’s “Isn’t It a Pity” to David Bowie’s “Loving the Alien” and Lenny Kravitz’s “Are You Gonna Go My Way.”

In addition to the elegant melodic heads in each song, the far-reaching album finds the 71-year-old guitarist evoking a similar modal majesty in his solos as he did on Frampton Comes Alive! and Humble Pie’s 1971 classic Performance: Rockin’ the Fillmore, but with an arguably more mindful delivery.

Perhaps, Frampton says, the encroaching physical limitations from his 2018 diagnosis of Inclusion Body Myositis (IBM) has informed a certain savoring of each note.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

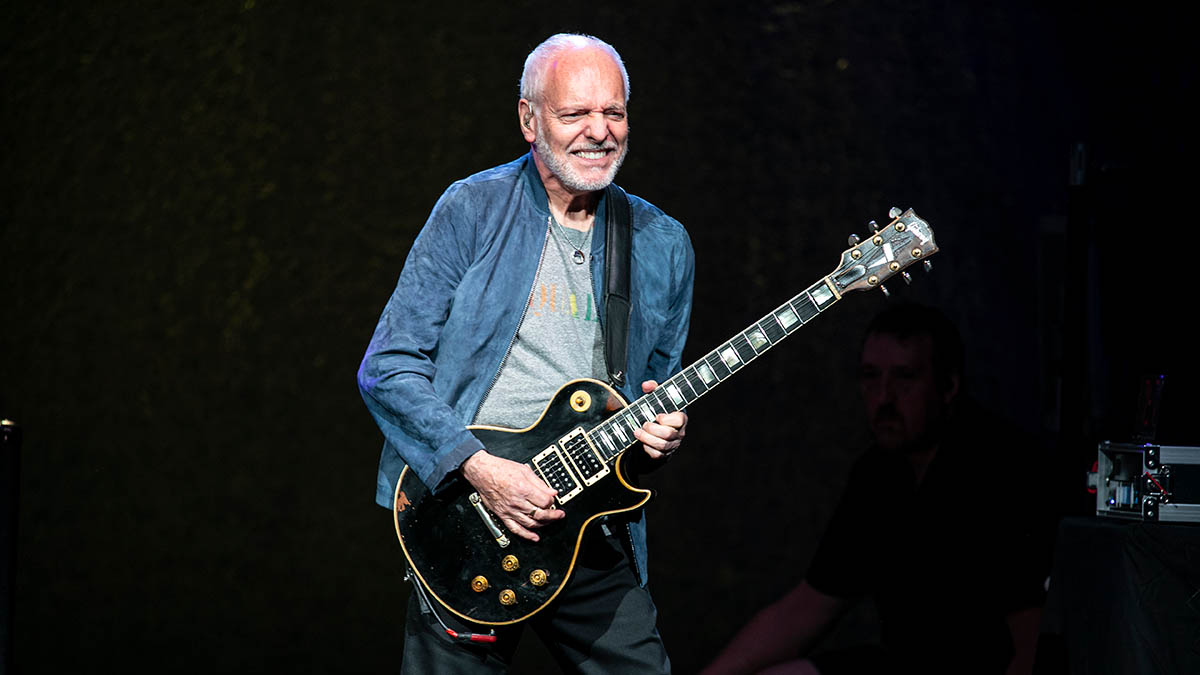

Following his diagnosis, Frampton set out in summer 2019 on what he billed as Finale: The Farewell Tour, where he skillfully, and with apparent joy, reached into his ample back pages, showering outdoor amphitheaters across the country with that roiling, Leslie-assisted churn on “It’s a Plain Shame” and “Doobie Wah,” and digging into the brisk, Les Paul–plus-Marshall bark of Humble Pie classics like “Four-Day Creep” and “I Don’t Need No Doctor.” But the sense that this really was his goodbye was a concerning one.

In conversation, Frampton remains upbeat, resilient, gracious and still allied with the same excitement that first stirred his desire to play as a kid, busking on the steps of Bromley Technical High School with a young David Bowie.

With the latest and most accurate signature version of his legendary, lost-and-found three-pickup 1954 Gibson Black Beauty – a.k.a. the Phenix – now in production at the Gibson factory in Nashville, Frampton, too, it seems, has once more risen to new heights and plumbed new depths as a player, producer, and performer.

As he wrote of his many ups and downs in his best-selling 2020 autobiography, Do You Feel Like I Do?, “I’ve been to the moon and back without a rocket. But I’ve always managed to stay optimistic. There’s always reason to hold out hope.”

I’m so fond of your phrasing and touch on this record. The vibrato is very careful and deliberate, and the tone feels really curated, as well. Is there wisdom coming to you as a player now that might not have been there 50 years ago when you played with Humble Pie?

It’s very hard to explain the things one does on a guitar, because I’ve been doing it for so long. I will say this: I do think that we are the sum of our years. We gain wisdom. I’ve been playing all my life. I’ve listened to many, many different players and many different pieces of music that I just love, and I will often sit down and play them note-for-note simply because I love them.

I so enjoy playing, as we all do as lifelong guitar players. Perhaps knowing now that I don’t have forever, I do believe it’s brought even more soul into my playing, if that makes sense

Now, what has perhaps played into this feeling you’re describing in my playing, along with having all these years of experience, is that, when I was diagnosed with IBM, my muscle disease, it was obviously a devastating diagnosis, knowing that one day certain muscles won’t work anymore, and those muscles are in my hands, which obviously I need as a guitar player.

I’d like to think that every time I play, I always put my heart and soul into it and play with a blank mind, if you will. I’ve done all the research, all the work required up until I get to that solo. So whatever it is I’m playing on guitar, I try to blank my mind out at that moment and just play and let it happen.

I do think that my predicament has brought out something else in my playing, yes, and I think it’s a feeling of... well, it’s both a happy and a sad thing. I so enjoy playing, as we all do as lifelong guitar players. Perhaps knowing now that I don’t have forever, I do believe it’s brought even more soul into my playing, if that makes sense.

Well, let me just confirm that there are some truly soulful moments on this record. Let’s talk for instance about your playing on the last song of the record, “Maybe,” originally performed by Alison Krauss, a fellow Nashvillian.

The reason I chose that song over many that I had on my wishlist was that my dear writing partner of many years, Gordon Kennedy, wrote that with Phil Madeira, who originally played it for Alison Krauss, and he sent their version of it to me shortly after it was recorded. It’s one of my all-time favorite songs, and you simply have to hear her sing it.

The reason I did “Isn’t It a Pity” goes back to the day in early 1970 when I went down to Abbey Road for the first time to play acoustic guitar on what would become George’s great classic, All Things Must Pass

As soon as we got our version mixed, the first thing I did was to send it to Alison because she inspired me so much with her voice on that track. If something gives me goose bumps – like I have right now just talking about Alison Krauss and this song – that’s what I want music to do for me.

This is also why I wanted to record a version of Jaco Pastorius’s “Dreamland.” Again, it’s one of my all-time favorite melodies, written by Jaco and the late Michel Colombier.

This was just a very gut-level thing: “I want to play this song – it’s calling to me.” I was at the very beginning of my exploration of Jaco’s melodic sense at that time, but I thought keyboardist Rob Arthur and I should give it a try.

We really just recorded it as an exercise, but we liked it so much that we decided to put the band on it as well. Again, this happened only because I wanted to play it as a personal tribute to Jaco and what he’s taught me. I love it when music happens like that.

In some ways, you’re revealing aspects of the tonalities of these songs by virtue of playing them as instrumentals – tonal qualities that maybe weren’t really magnified in the originals. A good example is George Harrison’s “Isn’t It a Pity.” The song has this very deliberate, mindful pace, and then there’s that G diminished chord – or one could hear it as a C-7b5 chord – and you just find so much space and color and melancholy there.

I’m not very well-versed in theory terms, but yeah, that particular chord is extremely important. In fact, somebody else in the band was playing it slightly differently than the original, and I said “No, that’s not it. That voicing changes the vibe of it.” I wanted that exact same feeling and mood.

Now, the reason I did “Isn’t It a Pity” goes back to the day in early 1970 when I went down to Abbey Road for the first time to play acoustic guitar on what would become George’s great classic, All Things Must Pass.

We recorded about six tracks over the course of 10 days or so. One morning, after a late tracking session, I walked into the control room and all the band were there, just starting to arrive, and George said to Phil Spector, “Play them ‘Isn’t It a Pity.’”

Well, the mix he played completely freaked me out. Every tape machine in the room was going, and the control room seemed like it was spinning. There was echo coming from who knows where and this huge swell of sound, though there’s probably only five people playing on the track.

It was so haunting. That chord is the one that triggers everything. It wouldn’t be anything if it weren’t for that one note change.

When I was studying your solos from Humble Pie, it was a great learning experience for me. [James Rotondi has been playing guitar for Jerry Shirley’s recent touring lineup under the Humble Pie banner, in tandem with former Bad Company guitarist Dave “Bucket” Colwell — Ed.]

You generally play “on the chord” inside a progression, but when you stretch out to play over vamps, what keeps coming up for many of us is the modal aspect of your playing. Along with partial chord rakes and arpeggios, we hear a lot of Dorian and Mixolydian mode in your playing. What was your “aha” moment with realizing what the elements were to creating your own style?

Well, I honestly don’t know what mode I’m in as a human being or a player. [laughs] Honestly, I’ve never known what mode I’m playing in. In fact, years ago, a dear friend of mine said, “You know you’re doing a Mixolydian mode here,” and I said, “What are you talking about?” And he sent me all the modes written out, and I realized, Oh, okay. That’s what they are, and I see why someone might interpret my playing along those lines. And then I put it down. I just don’t like to think too much about what I’m playing.

But I did have a big “aha” moment once, of the kind you’re describing. It was when Humble Pie recorded the Rock On album in 1971, and we did the song “Stone Cold Fever.”

I think I was out there with the guys for a few takes, and I’m playing my solo every take, and I’m going, Oh, gosh, I’m going to be worn out by the time I’m ready to do my solo overdub. So I stopped playing, and the three of them finished cutting the track.

We all came into the control room and listened to it. I listened to the guitar playing I’d done, especially the elongated solo part, the one I thought wasn’t even a keeper, and I got this great feeling. I said to myself, “I think I’ve just realized my own style; I think that all these years I’ve been listening to everyone and their mate play – and stealing things from them – are over.”

When this happens, suddenly, you can play the same lick as Eric Clapton and it doesn’t sound like Eric Clapton. You can play the same lick as Jeff Beck, but you’ll never sound like Jeff Beck again. From now on, you’re only going to sound like you.

Once you’ve learned all those things from other players, and then they settle in your subconscious, they’re in the library of information now, but that’s it. You’re the one in charge.

I realized at that moment, standing behind [producer] Glyn Johns as he played the track back with all the guys. That’s when I realized that I had achieved something that I’d always wanted to do.

I still had a long way to go, and I still feel like I have a long way to go. We’re never finished learning. But at that moment, I knew I was on the right track. I’d arrived at my unique voice on the instrument. All of a sudden, I had my style.”

- Peter Frampton Forgets the Words is out now via UMe.

- To make a donation to the Peter Frampton Myositis Research Fund, visit here

A former editor at Guitar Player and Guitar World, and an ex-member of Humble Pie, Mr. Bungle and French band AIR, author James Volpe Rotondi plays guitar for the acclaimed Led Zeppelin tribute, ZOSO, which The L.A. Times has called “head and shoulders above all other Led Zeppelin tribute bands.” Find JVR on Instagram at @james.volpe.rotondi, on the web at JVRonGTR.com, and look for upcoming tour dates at zosoontour.com