All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

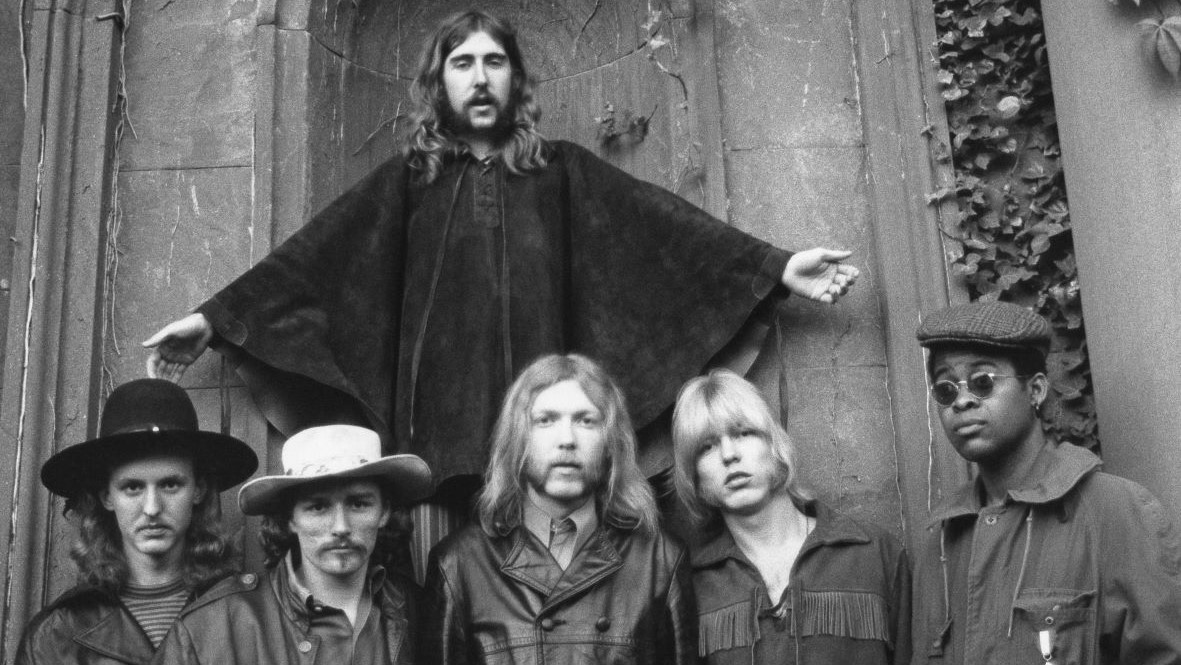

The Allman Brothers Band’s 1971 double album At Fillmore East is often and rightly proclaimed rock’s greatest live release. Fifty years on, it still sounds fresh, inspired and utterly original. It is the gold standard of blues-based rock and roll, but it’s easy to lose sight of what a radical album At Fillmore East really was.

It took a lot of guts for the Allmans and their record label to release a two-LP live album as their third release. After all, when it came out in July 1971, the band was something of a commercial flop.

Although they drew raves for their marathon live shows that combined the Grateful Dead’s go-anywhere jam ethos with a far superior musical precision, their first two releases caused barely a ripple in the marketplace. The band’s self-titled 1969 debut sold fewer than 35,000 copies, and the following year’s Idlewild South did only marginally better despite two singles, “Midnight Rider” and “Revival.” The band struggled to understand why.

Article continues belowWhen the first record came out at number 200 with an anchor and dropped off the face of the earth, my brother and I did not get discouraged.

Gregg Allman

“When the first record came out at number 200 with an anchor and dropped off the face of the earth, my brother and I did not get discouraged,” Gregg Allman recalled, a few years before his death in 2017. “But I thought Idlewild South was a much better record, and when that died on the vine, I thought, Damn, maybe we were wrong about this group.”

But the lackluster sales didn’t match the increasingly large and rabid crowds the band drew on its relentlessly paced tours. Fans loved the Allman Brothers’ rare combination of blues, jazz, rock and country, and their willingness to play until somebody pulled the plug. Finally, it dawned on the band and its management that a live album was the only way to capture the group’s real essence.

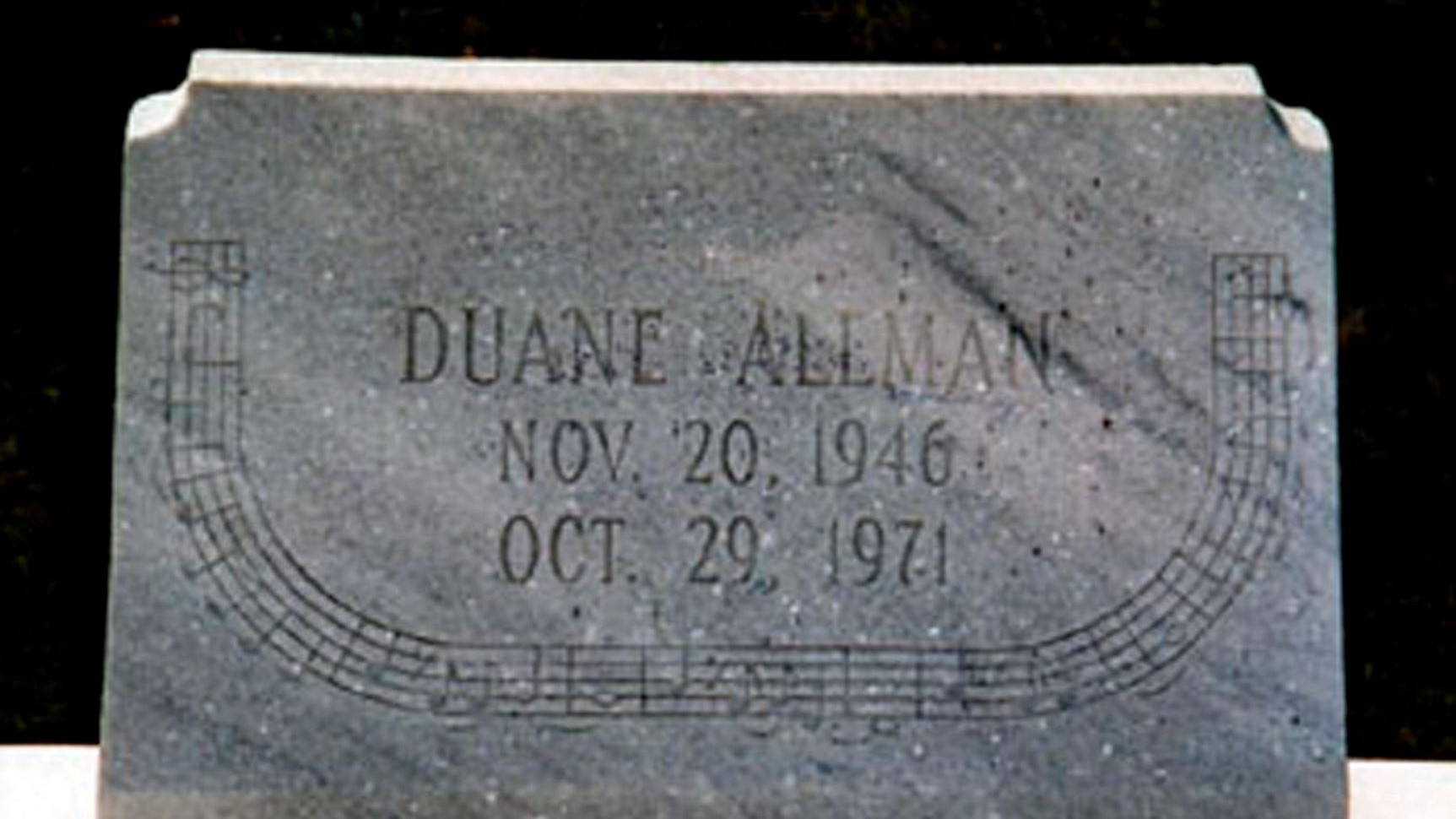

What resulted was a recording of two shows at New York City’s famed Fillmore East, an album that still stands as a testament to a great band at the peak of its power. Sadly, it would prove to be the final record completed by guitarist Duane Allman, who died shortly after its release. As such, it has become an epitaph for both him and the Allman Brothers Band 'Mark 1'.

The Allmans have always had a perpetual swing sensation that is unique in rock. They swing like they’re playing jazz...

Tom Dowd

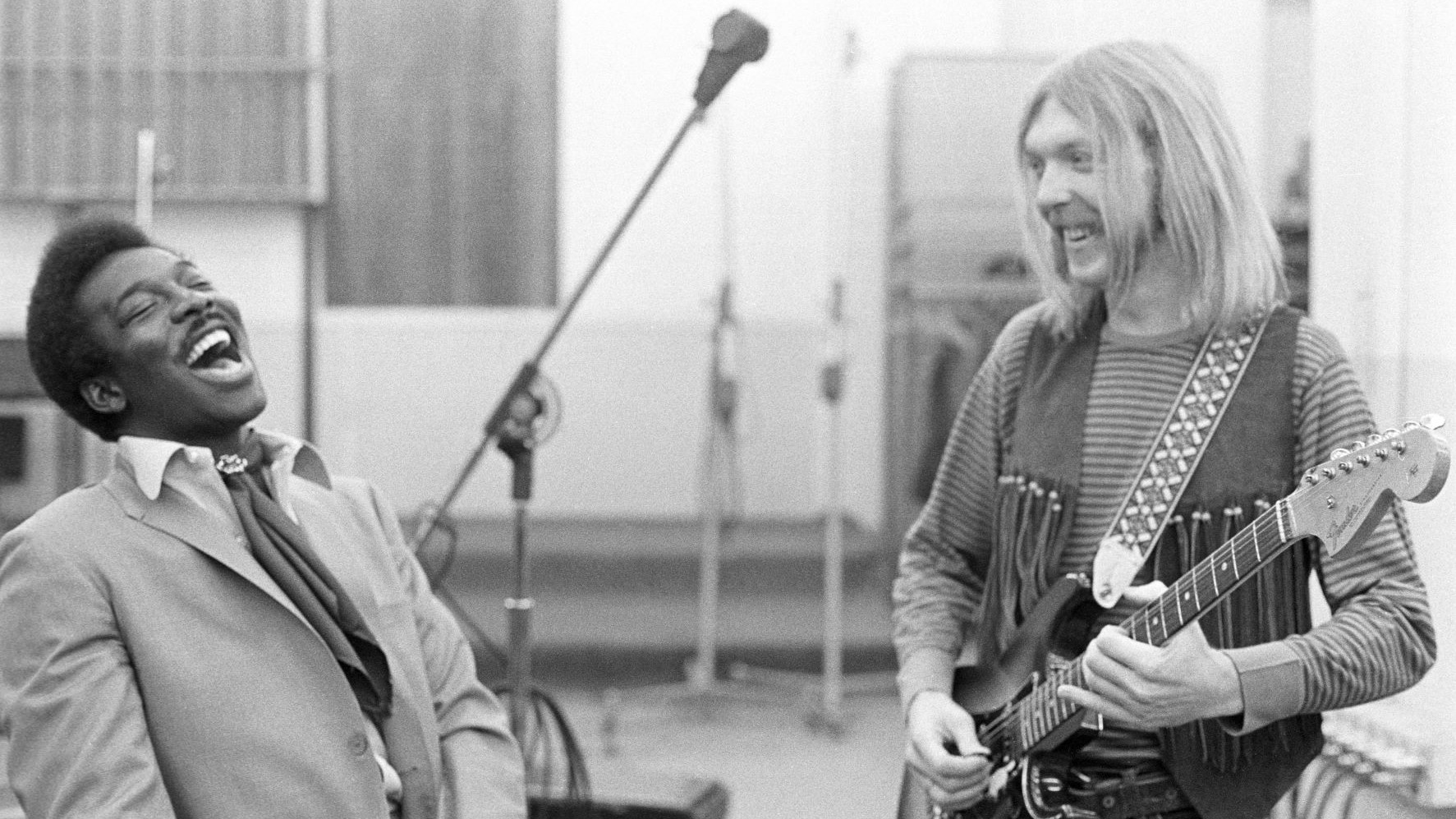

“That album captured the band in all their glory,” producer Tom Dowd said in a 1998 interview. Dowd, who died in 2002, was behind the boards for nearly a dozen Allman Brothers albums, including At Fillmore East, and worked with everyone from John Coltrane and Ray Charles to Cream and Lynyrd Skynyrd. “The Allmans have always had a perpetual swing sensation that is unique in rock. They swing like they’re playing jazz when they play things that are tangential to the blues, and even when they play heavy rock. They’re never vertical but always going forward, and it’s always a groove.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

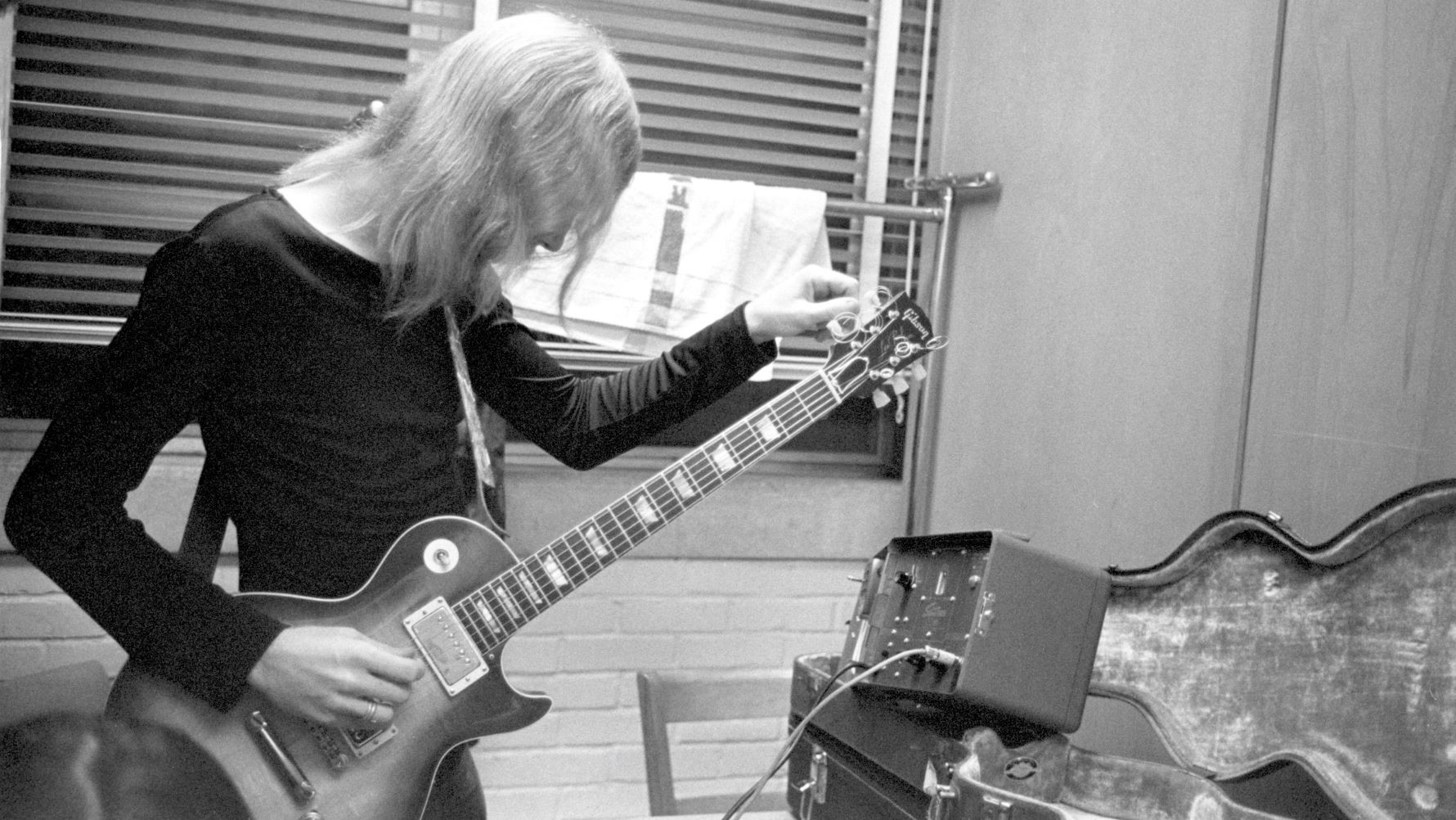

Certainly, the improvisation and length of the tunes on At Fillmore East was more similar to jazz than rock, with just seven songs spread over four vinyl sides, capturing the Allmans in all their bluesy, sonic fury. “You Don’t Love Me” and “Whipping Post” both occupied full album sides, while “In Memory of Elizabeth Reed” clocked in at 13 minutes. Still, from the clarion slide guitar of “Statesboro Blues” that opens the album to the booming timpani roll of “Whipping Post” that closes it, there is nary a wasted note in the 78 minutes of Fillmore’s music.

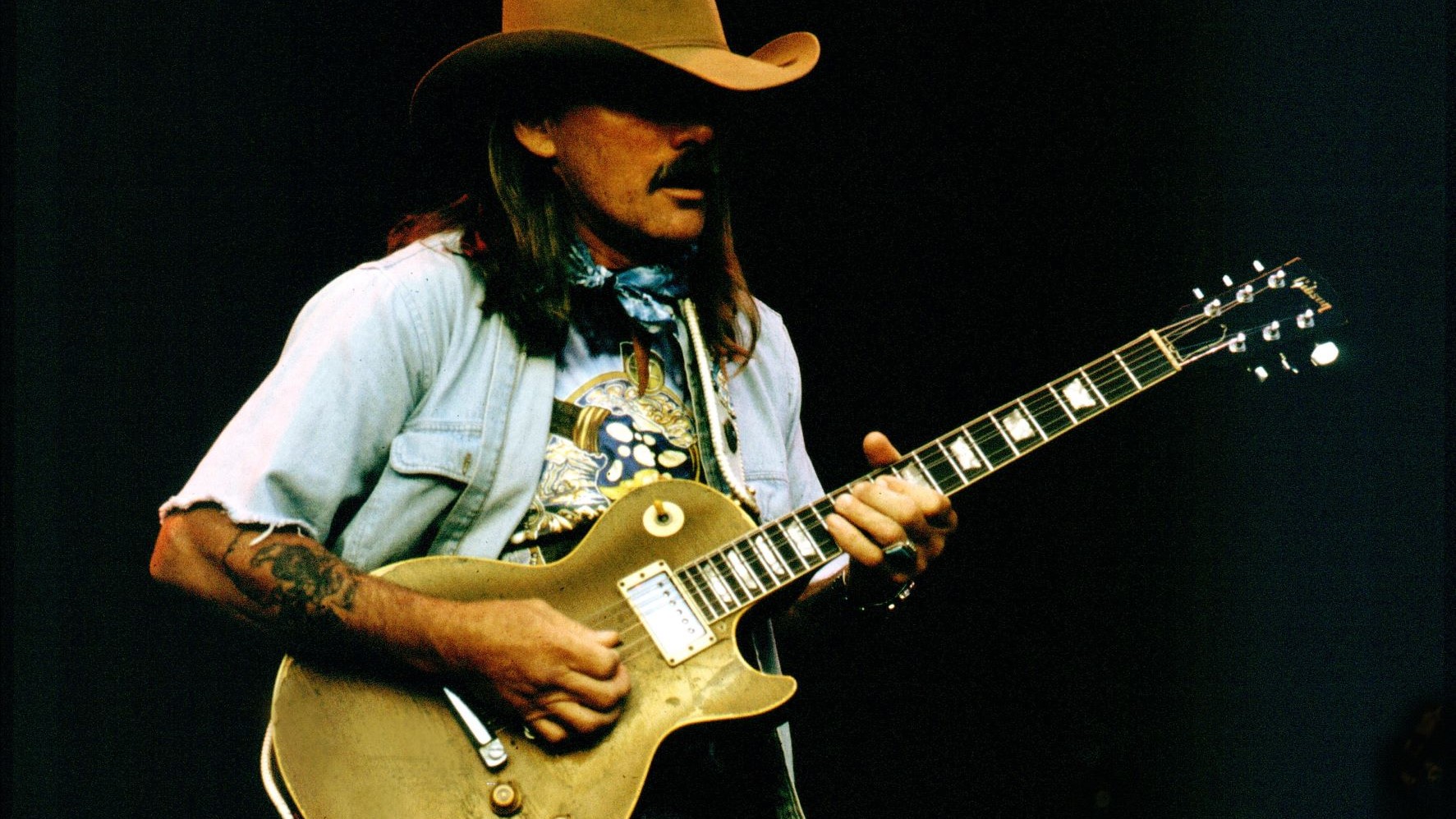

Propelled upward and onward by bassist Berry Oakley, whose free-range style uniquely roamed the middle of the band’s sound, and the rhythmic onslaught of double drummers Jaimoe and the late Butch Trucks, the group seemed ready to blast off in any direction at any time. Dickey Betts and Duane Allman spurred each other on to new heights of fretboard ferocity and creativity while pioneering guitar harmonies. Gregg Allman’s authentic blues singing and surging organ vamps kept even the most ambitious jams firmly rooted to terra firma.

There’s nothing too complicated about what makes 'Fillmore' a great album.

Dickey Betts

“There’s nothing too complicated about what makes Fillmore a great album,” Betts offers. “The thing is, we were a hell of a band and we just got a good recording that captured what we sounded like.” Adds Jaimoe, “Fillmore was both a particularly great performance and a typical night.”

To truly understand the album, it helps to recognize just how hungry and desperate the band was at the time of its release. Then-manager and Capricorn Records president Phil Walden readily admitted he had begun to consider cashing in his chips and cutting his losses.

“It seemed like I had just been wrong and that they were never going to catch on,” Walden, who died in 2006, said in a 1990 interview. “People just didn’t grasp what the Allmans were all about musically or any other way. But they kept touring, state by state, city by city, going across the country, establishing themselves as the best live band around, and building a base.”

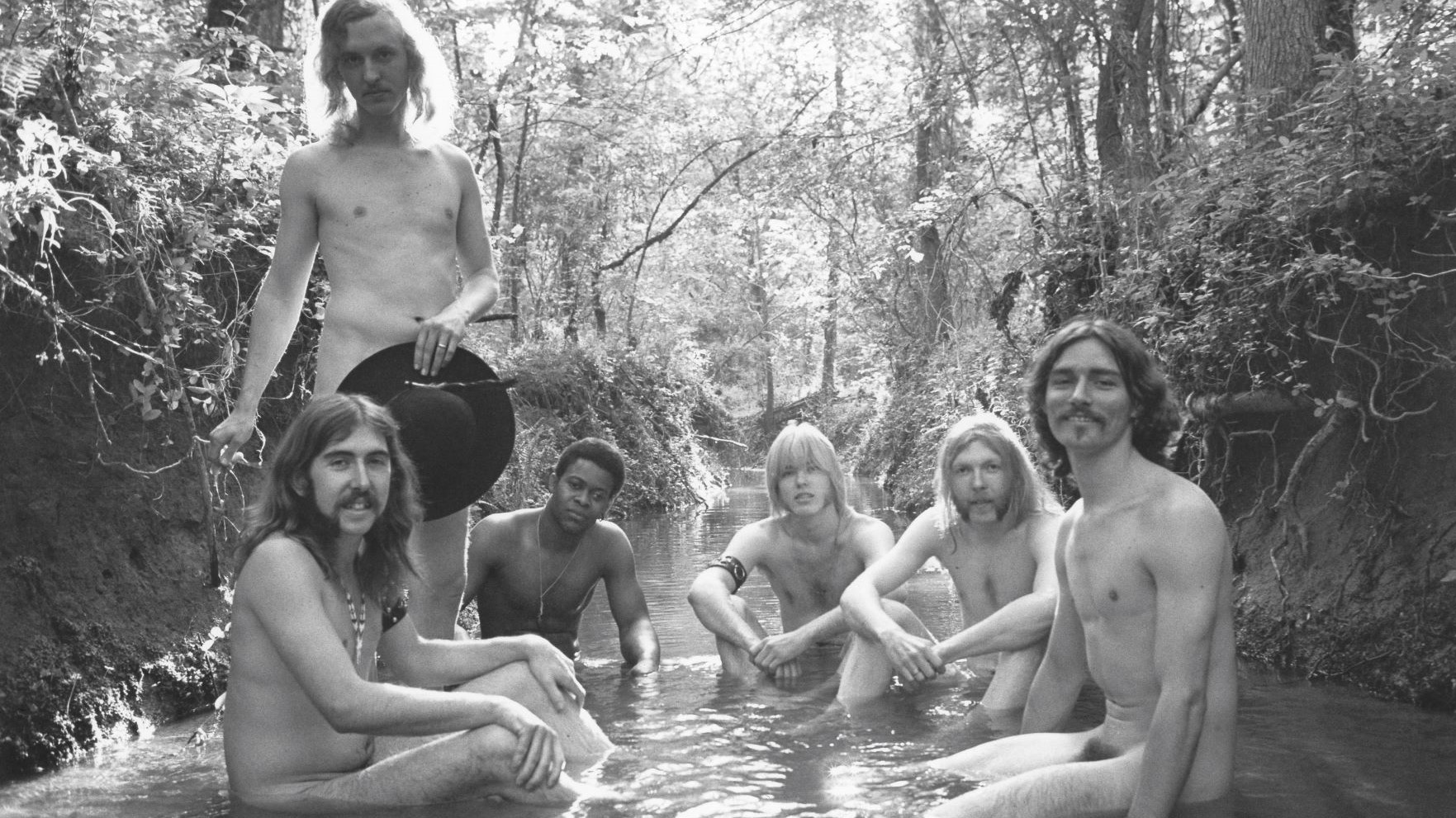

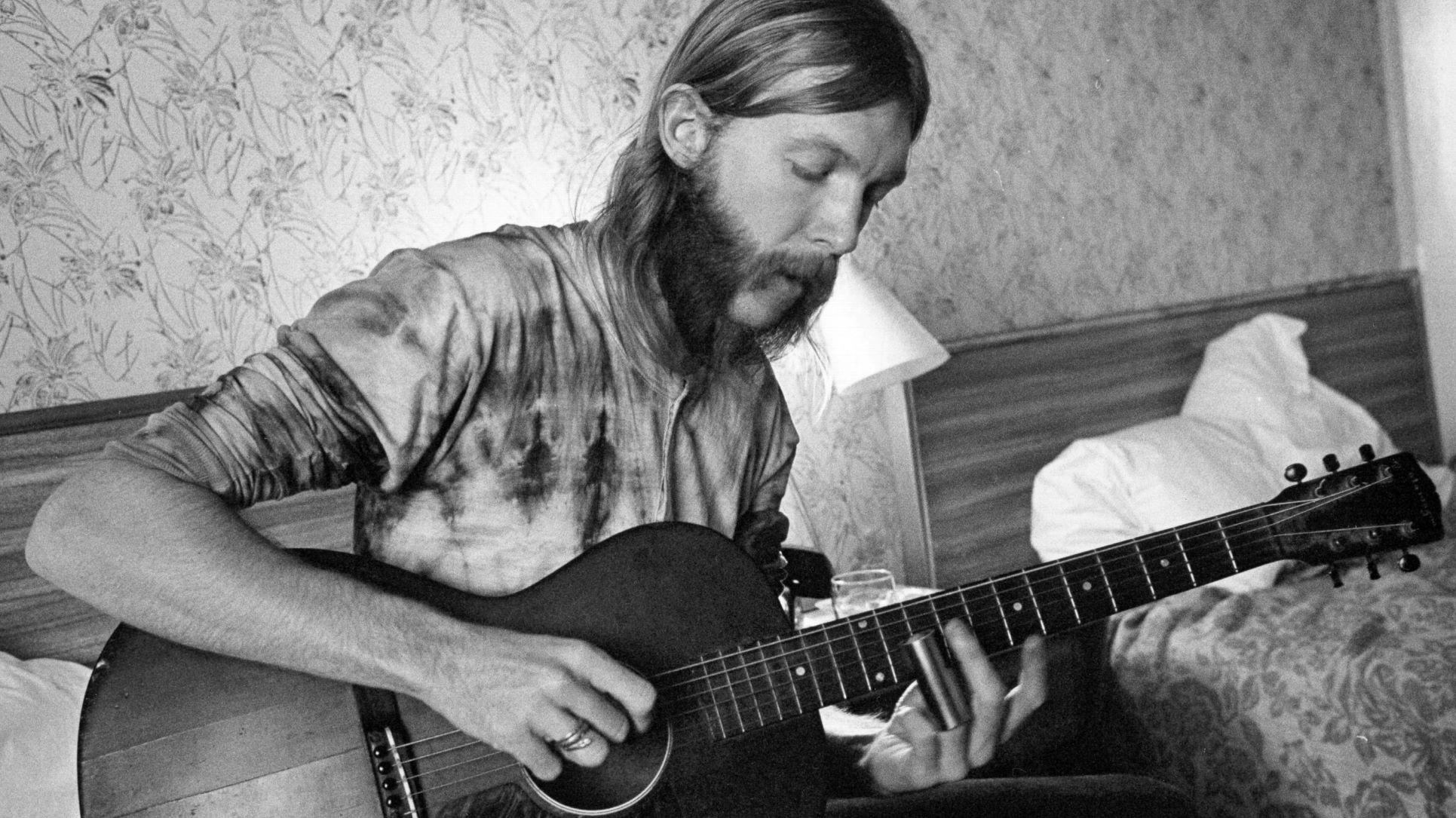

Gregg Allman said the band played more than 300 nights in 1970, traveling most of the off days, a claim that seems only a slight exaggeration. As they continued to crisscross the country, jammed together in first a Ford Econoline van and then a Winnebago, their sound evolved and deepened. It’s a process well known to the hardcore tape traders who exchange copies of these shows like so many pieces of holy grail. But there was a price to pay. “That kind of schedule puts a lot of wear and tear on your ass,” Allman said.

They kept touring, state by state, city by city, going across the country, establishing themselves as the best live band around, and building a base.

Phil Walden

Recalls booking agent Jonny Podell, “I started booking the band in June 1969. Phil Walden said, ‘Get them dates. I don’t care if it’s Portland, Oregon, on Monday and Portland, Maine, on Tuesday.’ I tried to do a little better, but that’s what we did, and they never complained. This was run like a machine, like a military unit. There were six in the band, and management provided them with first five, then six crew, making maybe $100 a night, which was pretty unusual for the time and really quite extravagant.”

The first two weeks of September 1971, just after At Fillmore East was released, provide a snapshot of the band’s grueling schedule. The Allmans played Montreal on September 3 and Miami the following night. They had five days off, during which they went into Miami’s Criteria Studios with Dowd and laid down the first tracks for Betts’ “Blue Sky,” which would appear on their next studio album, Eat a Peach. They then played September 10 in Passaic, New Jersey, the following night in Clemson, South Carolina, and the night after that in Shippensburg, Pennsylvania. The band then had three days off and played September 16 in New Orleans.

“Don’t ask me how we did it, because I don’t know,” the band’s onetime tour manager Willie Perkins offered. “My own naïveté probably helped me, because we just did what was asked and made the gigs that were booked. But God! We used to call them ‘dartboard tours,’ because it seemed like someone had made the bookings by throwing darts at a map. We were zigzagging everywhere.”

We simply realized that we were a better live band than studio outfit...

Gregg Allman

With all that hard touring paying off and their fan base steadily growing by word of mouth, the band decided that it needed to capitalize on its concert success. The solution became apparent: Record a live album.

“We simply realized that we were a better live band than studio outfit because we were always ready to experiment – offstage as well as on, I may add,” Gregg explained. “And the audience was a big part of what we did up there, which is something that couldn’t be duplicated in a studio. A light bulb finally went off: We need to make a live album.”

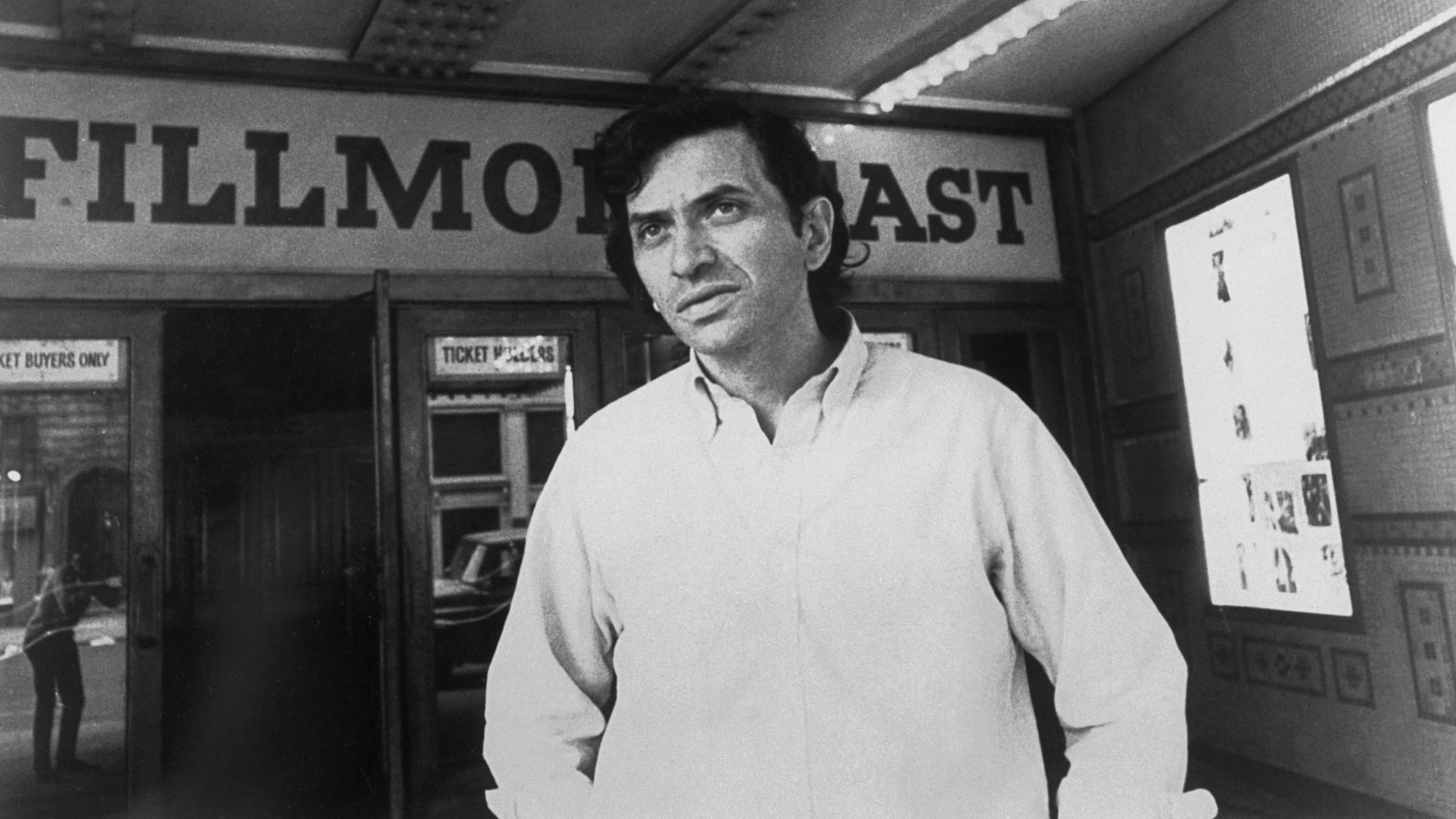

Once the decision to record live was made – not an obvious choice in 1971, when live rock albums were still in their infancy – the choice of venue was simple. Promoter Bill Graham was an early and important supporter of the band, booking the Allmans repeatedly in his bicoastal rock emporiums, the Fillmores East, in New York, and the Fillmore West, in San Francisco, where they established themselves as an elite band.

The Allman Brothers Band had made their Fillmore debut on December 26, 1969, opening for Blood, Sweat & Tears for three nights. Graham promised he would have them back soon and often, paired with more appropriate acts. Two weeks later, they opened four shows for Buddy Guy and B.B. King at the Fillmore West. The following month they were back in New York for three nights with the Grateful Dead. These shows were crucial in establishing the band and exposing it to a wider and more sympathetic audience.

Something particularly special was happening between the Allman Brothers and fans in New York, which remained their most supportive audience throughout their career (they played their final show there, at the Beacon Theatre, on October 28, 2014). In those dark ages of rock promotion, the Fillmores were a significant step above all other venues.

[Bill] Graham would gamble on acts... and he had taken a chance on the Brothers, which everyone appreciated and remembered.

Willie Perkins

“The Fillmores were so professionally run, compared to anything else at the time,” Perkins says. “And Graham would gamble on acts, bringing in jazz and blues and the Trinidad/Tripoli String Band, and he had taken a chance on the Brothers, which everyone appreciated and remembered. He never paid anyone top dollar at the Fillmore. A lot of bands went off to other promoters as a result, and Bill would feel like they had turned their back on him. But we loved playing there.”

“New York crowds have always been great,” says Betts, who parted ways with the Allman Brothers in 2000. “But what made the Fillmore a special place was Bill Graham. He was the best promoter rock has ever had, and you could feel his influence in every single little thing at the Fillmore.”

“He called a spade a spade – and not necessarily in a loving way,” Allman added. “Mr. Graham was a stern man, the most tell-it-like-it-is person I have ever met, and at first it was off-putting. But he was the most fair person, too, and after knowing him for while, you realized that this guy, unlike most of the other fuckers out there, was on the straight and narrow.”

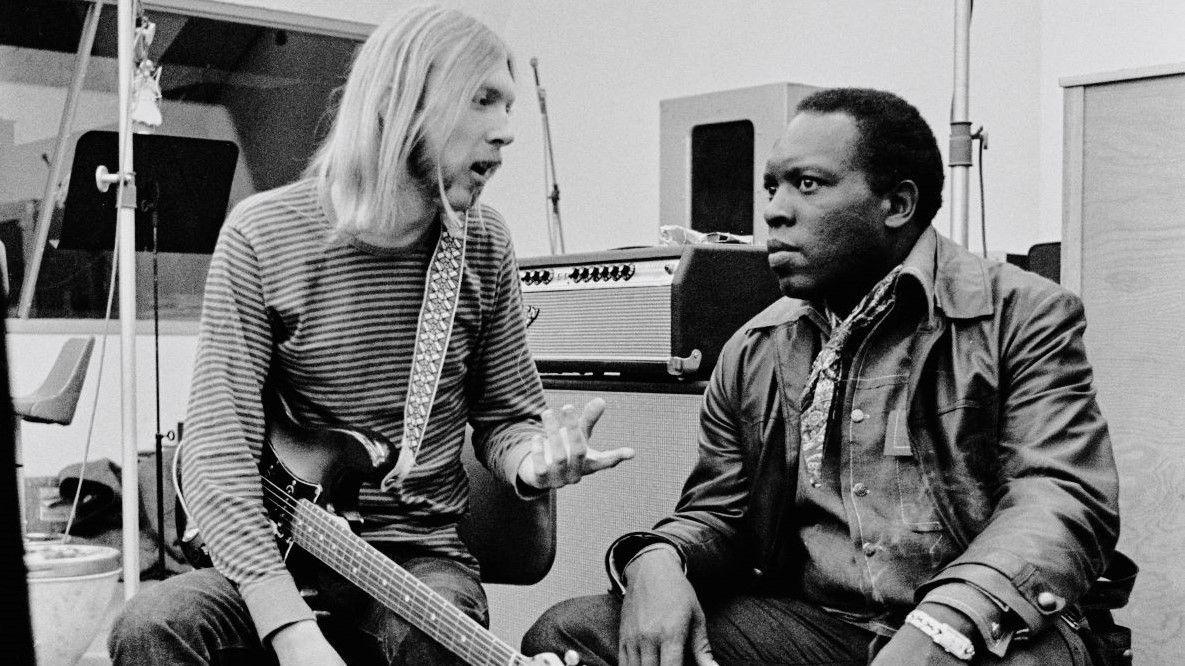

To cut the album, the band was booked into the Fillmore for three nights – March 11, 12 and 13, 1971 – as the middle act between opener Elvin Bishop and headliner Johnny Winter. The label and the band both wanted Dowd to produce the recording, but he was in Ghana working on recording the movie soundtrack for Soul to Soul, a concert featuring Wilson Picket, Aretha Frankin, Louis Armstrong, James Brown and Booker T & the MGs. “I got off a plane from Africa and called Atlantic to let them know I was back, and Jerry Wexler said, ‘Thank God! We’re recording the Allman Brothers live, and the truck is already booked,’” Dowd said. “So I stayed up in New York for a few days longer than I had planned.”

A mobile recording studio was parked on the street outside the theater, with Dowd and a small crew set up inside. “It was a good truck, with a 16-track machine and a great, tough-as-nails staff who took care of business,” Dowd recalled. “They were all set to go. When I got there, I gave them a couple of suggestions and clued them as to what to expect and how to employ the 16 tracks, because we had two drummers and two lead guitar players, which was unusual, and it took some foresight to properly capture the dynamics.”

I ran down at the break and grabbed Duane and said, ‘The horn has to go!’ and he went, ‘But he’s right on, man.’ And I said, ‘Duane, trust me, this isn’t the time to try this out.’

Tom Dowd

Years later, the band members insisted the horn would have worked out fine. “Juicy was playing baritone and would play basically along with the bass,” Gregg Allman said. “We knew we were recording three nights and probably just figured we’d get it the next night if it didn’t work out. We wanted to give ourselves plenty of times to do it because we didn’t want to go back and overdub anything, because then it wouldn’t have been a real live album. “

Adds Jaimoe, “Dowd started flipping out when he heard the horn, but that’s something that could have worked. There’s no way that it would have ruined anything that was going on. It wasn’t distracting anyone, and it was so powerful.” Betts probably sums up the Allman Brothers’ thought process best. “We were just having fun, and everyone dug it,” he says. Though it was wiped from a few tracks (no one can quite remember which), Doucette’s fine harp playing adds an extra dimension to “You Don’t Love Me” and “Done Somebody Wrong.”

We were just having fun, and everyone dug it.

Dickey Betts

“Doucette had played with the band a lot, so he was a lot more cohesive with what they were doing,” Perkins states. “Duane loved horns, but he would also listen to reason, and I don’t think he put up any fight with Dowd.”

Doucette was actually a frequent performer with the band, an old friend of Duane’s who had been offered a full-time position in the band but turned it down because he didn’t want it to “feel like a job.” “Duane was trying to shoehorn me in there,” Doucette explains. “He and I were great friends and we really liked playing together and hanging out. I wouldn’t trade playing in the Allman Brothers for anything, but they were complete. They didn’t really need me, and I wasn’t a joiner. I wanted my relationship with the band exactly how it was, and I asked Duane if I could do that. I said, ‘I’ll show up, I’ll play, you pay me, we’ll laugh and have fun, I’ll split.’”

I wouldn’t trade playing in the Allman Brothers for anything, but they were complete. They didn’t really need me, and I wasn’t a joiner.

Thom Doucette

The harmonica player says Duane not only wanted him as a member but fully intended to add a horn section to the Allman Brothers’ lineup. “The plan was to bring on the horns full time,” Doucette says. “Duane would have liked to have 16 pieces. Duane had six different projects that he wanted to do, and he just thought he could do it all at once on the same bandstand.”

Each night after playing, the band and Dowd would head uptown to the Atlantic Records studio and listen to playbacks of the night’s performance. “We would just grab some beers and sandwiches and go through the show,” Dowd explained. “That way, the next night, they knew exactly what they had and which songs they didn’t have to play again.”

The band was thrilled just to be able to listen back to what they had played, a rare occurrence at the time. “We loved having that opportunity,” Betts says. “We just thought, Hey, this is cool! I didn’t know I did that. That sounds pretty neat. We were just enjoying ourselves, because we would get a chance to listen to our performances. We didn’t do a lot of [mixboard] recordings, and we weren’t real hung up on the recording industry anyhow. We just played, and if they wanted to record it, they could.

“We were young and headstrong,” he adds. “‘We’re gonna play. You do what you want.’”

We just played, and if they wanted to record it, they could.

Dickey Betts

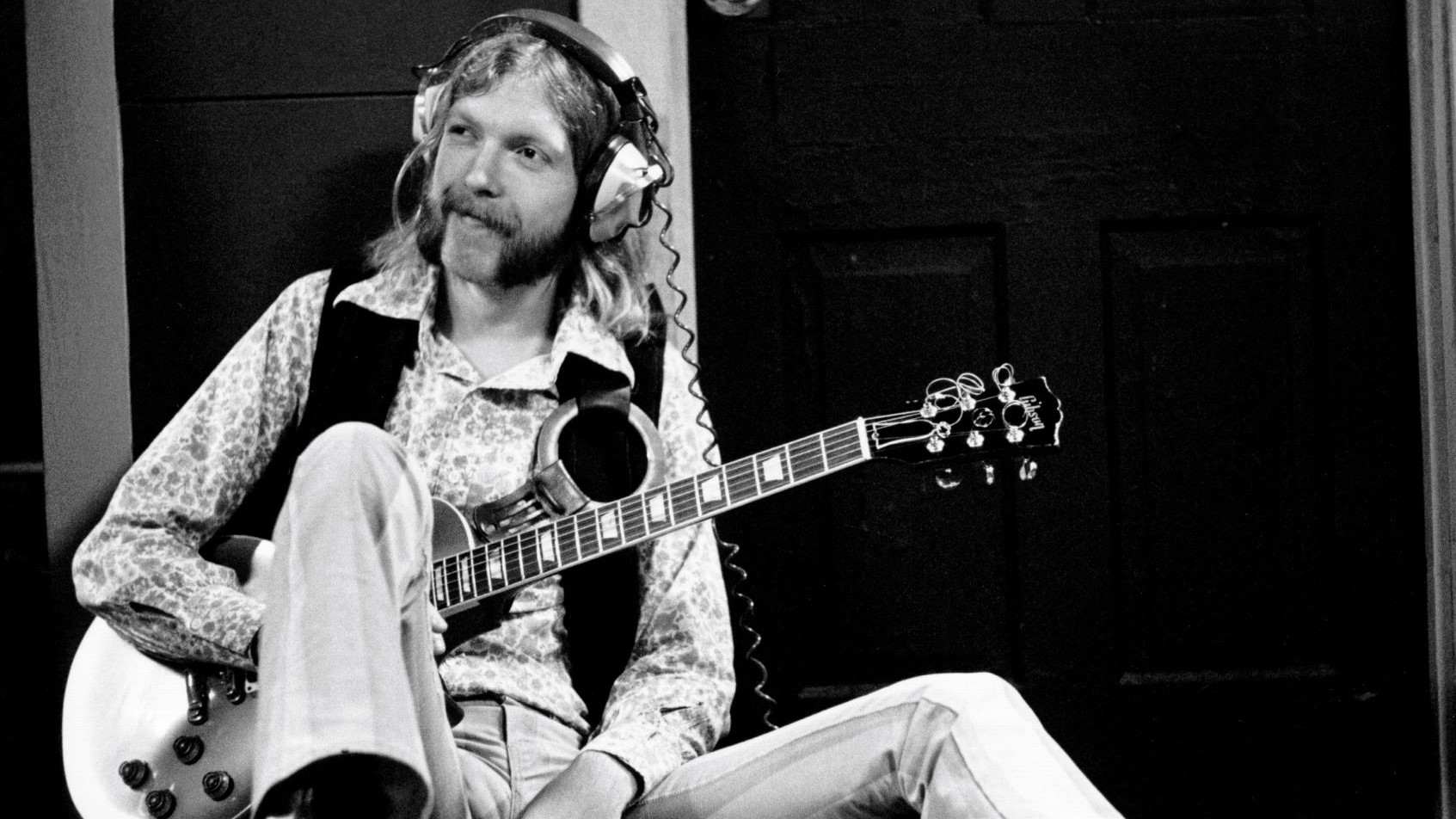

The power of the music captured on At Fillmore East was in the group improvisation, the fact that six extremely unique musical voices were expressing themselves as one complete entity. At the heart of the group’s sound was Betts and Duane Allman, who reinvented the concept of two-guitar rock bands. Rather than having one player who was primarily a rhythm player backing a soloist, the group had two dynamic lead players.

While Duane Allman is probably most remembered and revered for his dynamic slide playing, he was a fully formed, mature guitarist. Betts, while often in Allman’s shadow, was also a wide-ranging, distinct stylist from the start. The pair had a broad range of techniques for playing together, often forming intricate, interlocking patterns with one another and/or bassist Berry Oakley, setting the stage for dramatic flights of improvised solos. And, uniquely, they often played harmonies together, a true rock and roll innovation that has been picked up on by countless bands.

“From our first time playing together, Duane started picking up on things I played and offering a harmony, and we’d build whole jams off of that,” Betts says. “We worked stuff out naturally because we were both lead players. We got those ideas from jazz horn players like Miles Davis and John Coltrane and fiddle lines from western swing music. I listened to a lot of country and string [bluegrass] music growing up. I played mandolin, ukulele and fiddle before I ever touched a guitar, which may be where a lot of the major keys I play come from.

“It’s very hard to go freestyle with two guitars. Most bands with two guitarists either have everything worked out or stay out of each other’s way, because it’s easy to sound like two cats fighting if you’re not careful. But it was very natural how Duane and I put our guitars together. He would almost always wait for me, or sometimes Oakley, to come up with a melody, and then he would join in on my riff with the harmony.”

It was very natural how Duane and I put our guitars together. He would almost always wait for me, or sometimes Oakley, to come up with a melody, and then he would join in on my riff with the harmony.

Dickey Betts

The two drummers had a similarly easy and unique playing style, heard to full and perfect effect on At Fillmore East. Trucks and Jaimoe rarely played the same thing at the same time. Instead they played complementary parts that pushed the band to great heights and offered not only increased power but greater depth. Trucks provided a hard-driving beat while Jaimoe deepened the groove and pushed up against the songs with all kinds of interesting concepts and rhythms. Jaimoe was deeply rooted in jazz and often played patterns and riffs straight off of Jimmy Cobb’s work on Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue album. He had also introduced the band to the album and to John Coltrane, both of which had a huge impact on the Allmans. This jazz influence can be heard throughout the expansive but never long-winded playing on At Fillmore East.

The symbiotic relationships between the two drummers and two guitarists carried throughout the band, which functioned like one organism with a single giant beating heart. Says Doucette, “You take any one of the six guys out and the whole thing doesn’t exist. This was a band of men. There weren’t any kids in it, despite our young ages. We’d all worked. We’d all been on the road and taken responsibility, and it came through in the music.”

Also central to their strength and appeal was the depth and maturity of Gregg Allman’s songwriting and singing. Though just in his early 20s, he conjured up the power and world-weary heaviness of the greatest blues singers. Recalls Doucette, “I knew Duane for a long time but had never heard Gregg sing until the first time I played with the Allman Brothers Band. Gregory starts playing that organ and singing, and I went, Woah. Now here’s a guy who’s in worse pain than I am. He pushed all that pain into his music and combined it with his artistry into something very special and unique.”

He pushed all that pain into his music and combined it with his artistry into something very special and unique.

Thom Doucette

Doucette recalls another Fillmore East date when Albert King came to jam with the group on a slow blues. “He’s up there in a lime-green suit, sucking on his pipe and doing his thing,” he says. “Then Gregg starts singing, and Albert damn near bit through his pipe. He’s never heard this voice before, and he’s looking around, literally swiveling his head trying to figure out who’s singing, and he sees this skinny blonde behind the organ just killing it and couldn’t believe it was him.”

Using only the last two nights recorded at the Fillmore, the Allman Brothers ended up with enough great material left over to fill more than half of their follow-up album, Eat a Peach, including the epic nearly 44-minute “Mountain Jam,” performed directly after the 23-minute “Whipping Post” heard on Fillmore.

“We just felt like we could play all night, and sometimes we did,” Betts recalls. “We could really hit the note. There’s not a single fix on Fillmore. Everything you hear there is how we played it.”

There’s not a single fix on Fillmore. Everything you hear there is how we played it.

Dickey Betts

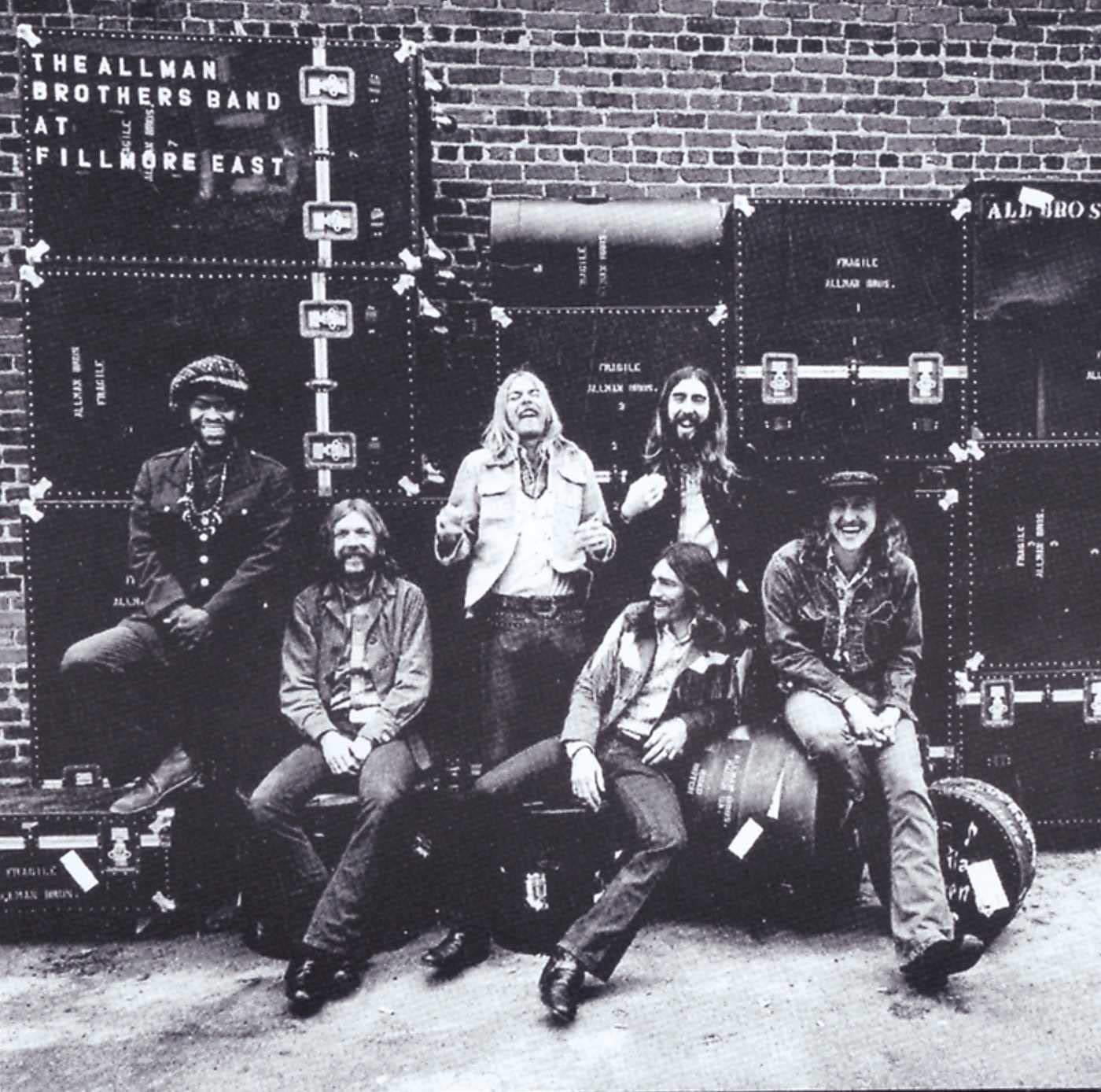

A few months after cutting the album, the members were in Capricorn Records’ Macon, Georgia, studio laying tracks when they learned that the live album was done and cover art had to be selected immediately. “We wanted to come up with something, because, left to their own devices, the people at Atlantic did horrible things,” Gregg recalled. “I mean, these were the people who superimposed a picture of Sam and Dave onto a turtle [for the cover of the soul duo’s Hold On I’m Coming album]! We wanted to make sure that the cover was as meat and potatoes as the band, so someone said, ‘Let’s just take a damn picture and make it look like we’re standing in the alley waiting to go onstage.’”

Photographer Jim Marshall arrived and snapped the group sitting on their road cases outside the Macon studio. “We were up at daylight to take the photo for the album cover, and we were all in a real grumpy mood,” Betts recalls. “The photographer wanted us out there then, and we thought it was dumb. We figured it didn’t make a damn bit of difference what the cover was or what time we took it. This dude Duane knew came walking down the sidewalk, and Duane jumped up and ran over and got a joint from this guy, then came back and sat down. We were all laughing, and that’s the photo captured on the cover. If you look at Duane’s hand, you can see him hiding something there. He had copped and sat down with a mischievous grin.”

Duane jumped up and ran over and got a joint from this guy, then came back and sat down. We were all laughing, and that’s the photo captured on the cover.

Dickey Betts

On the backside of the album, the crew stood in the musicians’ place, probably the first and last time roadies have ever been so prominently featured on an album cover. “That was my brother’s idea,” Gregg revealed. “The crew always played a special role in our band. It goes back to the very beginning, when we lived off the disability checks of Red Dog and Twiggs [Lyndon, tour manager]. It was like, ‘Want a job? Got any money?’ Putting them in a damn picture was the least we could do. They were the unsung heroes.”

The crew members at the time considered themselves a part of the band. They were paid the same $90-a-week salary, and the word was Duane issued an edict that if money was tight the crew should always be paid first. “We felt like we were part of the band,” says crew member Kim Payne, one of those featured on At Fillmore East. “It was truly more of a brotherhood than any kind of employee/employer relationship. Everyone was equal.”

Adds road manager Perkins, “Once, on my birthday, Duane asked for a $100 advance. I said, ‘Are you sure? You’ve already taken a lot,’ and he said, ‘I’m sure.’ So I filled out the receipt, he signed it, I gave him $100 and he handed it to me and said, ‘Happy birthday. Make sure that goes to my account and not the band’s.’”

“Duane truly appreciated everybody and understood that everybody was a piece of a puzzle,” Jaimoe says. “We all play together and every part is equally important, and that goes for the bus driver too. What you gonna do? Play all night and then drive the bus? Duane always said, ‘We’re all equal in this band.’ And that included the crew.”

Just 90 days after recording the album and just before its release, the Allman Brothers Band closed the Fillmore East down. The group was personally selected by Graham to be the hallowed venue’s final band after he had shocked everyone by announcing he was shutting the doors. “He closed the Fillmore with three nights and wanted us on all three, which I though was the kindest gesture and coolest thing,” Allman said.

The Beach Boys showed up and unloaded all their stuff and said they’d have to play last, and Graham said, ‘Well, just pack up your shit. I have my closing band.'

Butch Trucks

“We were just dumbstruck when we found out that we were gonna close the Fillmore,” Butch Trucks said. “Can you think of a bigger honor at that time? Everyone wanted in on that gig. The Beach Boys showed up and unloaded all their stuff and said they’d have to play last, and Graham said, ‘Well, just pack up your shit. I have my closing band.' So the Beach Boys had to swallow their pride.

“The next-to-last night, we played until the morning, and we did things that we had never thought of before or since. Those are the moments that have always made this thing work.”

Graham’s insistence that the relatively unknown Allman Brothers must be the Fillmore East’s final band must have seemed bold, even wacky, to most observers. But just weeks after the club shuttered its doors for good, At Fillmore East came out, forever linking the band and the venue in the pop-culture pantheon. Yet, the recording was almost never released in its extended, double-album form. “Atlantic/Atco rejected the idea of releasing a double-live album,” Walden said.

“[Atlantic executive] Jerry Wexler thought it was ridiculous to preserve all these jams. But we explained to them that the Allman Brothers were the people’s band, that playing was what they were all about, and that a phonograph record was confining to a group like this.”

Walden won out and was proven right when the record – “people priced” at three dollars below standard list for a double album – slowly became a hit and the Allman Brothers became the most heralded band in the nation. Rolling Stone proclaimed the Allmans “the best damn rock ’n’ roll band” in the country, and by the fall, At Fillmore East was the Allman Brothers Band’s first Gold album. “All of a sudden, here comes fame and fortune,” Gregg recalled. “In a three- or four-week period, we went from rags to riches – from living on a three-dollar-a-day per diem to, ‘Get anything you want, boys!’”

In a three- or four-week period, we went from rags to riches – from living on a three-dollar-a-day per diem to, ‘Get anything you want, boys!’

Gregg Allman

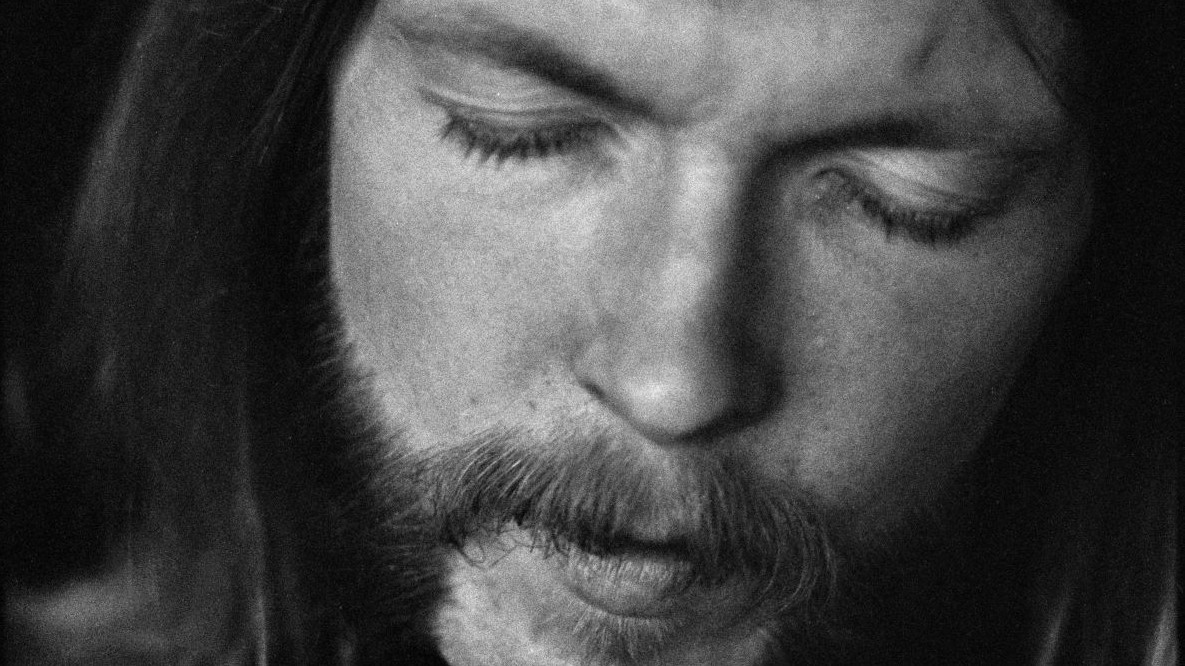

Still, things were not easy within the band. They entered Criteria Studios with Dowd and recorded three songs in just about a week, then took a break and returned to the road for a short run of shows, ending on October 17, 1971, at the Painter’s Mill Music Fair in Owings Mill, Maryland. It had been a trying few months, with drugs and the band’s hard-charging lifestyle catching up with many of them, including Duane.

“Duane never stuck a needle in his arm, but he would snort heroin a lot,” Trucks said. “One night in the summer of ’71, in San Francisco, Duane followed me to my hotel room and jumped in my face. He said, ‘I’m pissed off! When Dickey gets up to play, the rhythm section is pumping away, and when I get up there you’re laying back and not pushing at all.’ I looked him dead in the eye and said, ‘Duane, you’re so fucked up on that smack that you’re not giving us anything.’

“He looked me in the eye and walked out the door. I think he knew I was telling him the truth and that’s what he wanted to hear. He needed someone to tell him what he already knew. It was one of the few times I had the balls to get in his face.”

“It was nuts,” Doucette adds. “Everything was everywhere.”

I looked him dead in the eye and said, ‘Duane, you’re so fucked up on that smack that you’re not giving us anything.’ He looked me in the eye and walked out the door. I think he knew I was telling him the truth and that’s what he wanted to hear.

Butch Trucks

With almost everyone in the band and crew struggling with heroin addictions, Duane, Oakley, Payne and crew member Red Dog flew to Buffalo and checked into the Linwood-Bryant Hospital for a week of rehab. A receipt shows the band’s general bank account purchased five round-trip tickets on Eastern Airlines from Macon to Buffalo for $369. Gregg was supposed to go as well, and a hospital receipt shows he was one of the people for whom a deposit was paid. Apparently, he changed his mind at the last minute.

The group spent less than a week in rehab, and then checked out. Duane spent a day in New York City, visiting with guitarist John Hammond and other friends. “He came over to my loft and we played acoustic guitars and had a blast for hours,” Hammond recalls. “I so wish I had taped it! He seemed to be in really good spirits, his head clear and excited to go on. Things were happening for them. The live album had come out and was a hit, and they were playing bigger places. Their star was rising. Which seemed exactly as it should be.

“We talked about him perhaps producing an album for me. There were all these songs that I played in my show that I talked to him about recording, and he said that he would like to be involved. There was nothing concrete, but he was talking business: what percent he would take, and this and that. I was not a business guy like that, and he was very together about the band, his finances, dealing with the business end of things. He was a very bright guy who knew how talented he was and wasn’t going to take himself lightly.”

Duane returned to Macon on October 28, 1971. That night, he visited Red Dog, the roadie who had been in rehab with him and whose loyalty to the guitarist was profound enough to call him an acolyte. “He wanted to make sure I wasn’t going to slide back into doing heroin, to make sure I was all right,” Red Dog recalled in a 1986 interview. “He sat on my couch, squeezing my arm and looking me right in the eye, and said, ‘You haven’t done any, have you?’ and I said, ‘No, man.’ And I fired right back on him: ‘Hey, have you?’”

The next day, Duane called Thom Doucette in Florida to check in on his old friend. Doucette had abruptly left the band on the road and returned home because of his own struggles with addiction. He had cleaned himself up and was thrilled to hear a vitality in his friend’s voice that indicated he too was overcoming his problems.

“He sounded great,” Doucette says. “He jumped through the phone, with an urgency in his voice, that shouted, ‘It’s me. It’s Duane! I’m back!’

“He goes, ‘You doing all right?’ and I said, ‘Man, never better. I’m grooving and the fish are running. This is it, baby.’ He said, ‘I’ll be down tonight. I already booked a reservation. I’m gonna ride down to the office, get my mail and get some money. We’ll go fishing, and then we’re going back to work.’ I wasn’t so sure about going back to work with the band, but I was so happy to hear from him.”

Shortly after hanging up with Doucette, Duane rode his motorcycle over to the group’s communal home, The Big House, where they were getting ready for a birthday party for Oakley’s wife, Linda. After visiting for a while, Duane got on his Harley-Davidson Sportster, which had been modified with extended forks that made it harder to handle.

Coming up over a hill and dropping down, Duane saw a flatbed lumber truck blocking his way. He pushed his bike to the left to swerve around the truck, but realized he was not going to make it and dropped his bike to avoid a collision. He hit the ground hard, the bike landing atop him. Duane was alive and initially seemed okay, but he fell unconscious in the ambulance and had catastrophic head and chest injuries. As word of the accident began to circulate to band members and other family friends around Macon, many people began to drift toward the waiting room at the medical center.

“I was at my house when I got the call and went to the hospital,” recalls band friend and producer Johnny Sandlin. “I was hoping it wasn’t too bad and was planning on going in to see him. Guys were ending up in the emergency room from messing around with horses or bikes all the time.”

It was just unacceptable that he was gone. Unfathomable. I walked around stunned for weeks.

Butch Trucks

As the group gathered, someone emerged from the operating room with the unthinkable news: Duane had died in surgery three hours after the accident. The cause of death was listed as “severe injury of abdomen and head.”

“It was just unacceptable that he was gone,” Trucks remarked. “Unfathomable. I walked around stunned for weeks.”

At his funeral, Red Dog placed a joint in Duane’s pocket. Gregg gave his brother a silver dollar. Someone else added one of the Coricidin bottles Duane used as slides.

“We were all in shock,” Linda Oakley said. “It was like our guts had been torn out.”

Cowboy guitarist Scott Boyer, an old friend of Duane and Gregg’s summed up the feeling of the entire band and larger musical community: “It was inconceivable how someone that alive could be dead.”

It was inconceivable how someone that alive could be dead.

Scott Boyer

Duane had lived to see the band’s breakthrough coming, but was not able to fully experience it.

“We worked so hard so long to get there. Then, bam! He was gone,” Gregg Allman said. “At the time, I thought, Shit, my brother really got shortchanged, because he never quite got to see what he had accomplished. I felt that way for years, but I’ve slowly come to realize that he left a hell of a legacy for dying at the age of 24 years old. And a lot of it has to do with the Fillmore album. I still listen to it and I marvel at how fresh his licks are and how great his tone is. That boy was one of a kind, man, just like Oakley was. The chance that all six of us would meet up and form a band is, like, unbelievable.”

Allman paused for a second to exhale a long breath and lets out a little chuckle.

“If you want to hear what I’m talking about, go get you that album.”

Alan Paul is the author of three books, Texas Flood: The Inside Story of Stevie Ray Vaughan, One Way Way Out: The Inside Story of the Allman Brothers Band – which were both New York Times bestsellers – and Big in China: My Unlikely Adventures Raising a Family, Playing the Blues and Becoming a Star in Beijing, a memoir about raising a family in Beijing and forming a Chinese blues band that toured the nation. He’s been associated with Guitar World for 30 years, serving as Managing Editor from 1991-96. He plays in two bands: Big in China and Friends of the Brothers, with Guitar World’s Andy Aledort.