“She wasn’t feeling very good those days. The longer it went on, the worse it got.” The long road to Lucinda Williams’ breakthrough album — and the creative partnership that didn’t survive it.

Gurf Morlix recalls his journey with Williams that led to her greatest success and his decision to step away

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

History remembers Car Wheels on a Gravel Road as Lucinda Williams’ breakthrough — an album that helped define Americana and reshaped the singer-songwriter landscape.

Gurf Morlix recalls it differently. As Williams’ former guitarist and bandleader, his stylistic touch and musical fingerprints are all over the record and the three years it took to create it. The album’s liner notes bear this out in a brief but telling dedication: “To Donald, Ciambotti & Gurf: Thanks for the years of hard work & joy & the blood you sweat over this.”

But long before Car Wheels became a touchstone, Morlix was grinding it out on the margins, shaped by a hard-earned realism that never left him.

As an aspiring musician in Buffalo, New York, Morlix felt trapped in a local scene that “didn’t really seem conducive to making a living.” He wasn’t looking for hits or fame; Morlix was an old-school man’s-man type with a big heart and a warm, outlaw-country tone that felt pulled from an earlier era — music built for the twang-hungry faithful rather than the charts.

Still, nothing came easily.

“I had a bit of talent,” he tells Guitar Player. “But I couldn’t find like-minded people who wanted to play the same kind of music I did.

“I decided that Austin was the place to go — a great live music scene, hip college town and cheap rent. I was in heaven.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

So began the first of many moves that would define his life and career.

Lucinda Williams was part of that same Austin ecosystem, although Morlix didn’t meet her there. By the mid ’80s, he had pushed further west to Los Angeles, where their paths finally crossed.

“I’d moved out there ‘cause the Austin music scene started seeming a little small for me,” Morlix says. “She came out from Austin to do a sorta high profile gig. She was rehearsing a band of L.A. musicians. Her guitar player, David Grissom, was gonna fly out from Austin for the gig, but they asked me if I’d do some of the rehearsals just for fun.”

I had a bit of talent. But I couldn’t find like-minded people who wanted to play the same kind of music I did.”

— Gurf Morlix

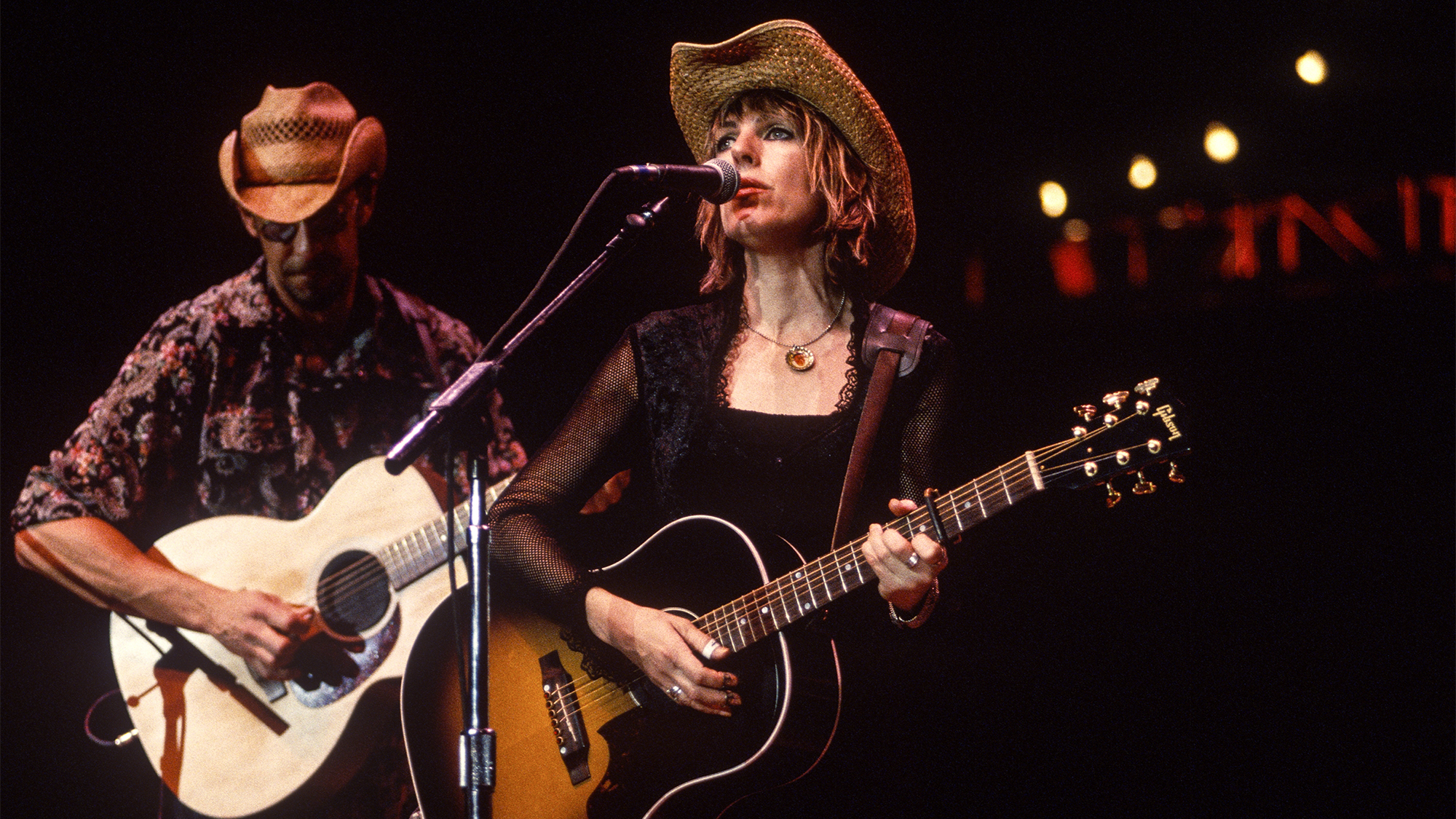

The chemistry was immediate, and Morlix soon became a fixture in Williams’ band. By the late ’80s he was serving as her bandleader.

“It worked well,” he says. “After a while, she moved out there, and I fell into playing with her. Bass, at first, and then lead guitar. We started doing gigs, and it worked well.”

Creatively, the two were aligned in a way that felt effortless. “It just worked organically,” Morlix explains. “She’d play me a new song, and I’d start playing along. Usually, I’d come up with the musical hooks right there, on the first or second pass. It was so natural.”

By 1988, Williams was ready to record her first album since 1980’s Happy Woman Blues. Until then, commercial success had eluded her. That changed with Lucinda Williams.

“We weren’t sure what would happen,” Morlix explains. “We had to do it really fast because of financial considerations and time constraints. We barely had any time to think. We made it in a week or two.”

The response was immediate and emphatic. Critics raved, and Williams was suddenly being mentioned alongside the era’s most respected songwriters, thanks to songs like “I Just Wanted to See You So Bad” and “Passionate Kisses.” The album is often credited with helping launch the alt-country movement. Morlix — as its producer, bandleader, and guitarist — was stunned by the reaction.

“It got played around the country,” he recalls, “though we didn’t know it. They cobbled together a national tour, and we were completely surprised to find lots of people showing up at the shows.”

Momentum carried Williams into the ’90s and 1992’s Sweet Old World, a slicker, more polished record that proved her success was no fluke. That same year, Mary Chapin Carpenter scored a major hit with her cover of “Passionate Kisses,” earning Williams a Grammy for Best Country Song at the 1994 awards.

I was trying to grow. I didn’t want to make another ‘Sweet Old World.’”

— Lucinda Williams

For Morlix, however, the shine was wearing off. The larger budget for Sweet Old World brought new pressures — and new frustrations.

“And lots of time to overthink things,” he says. “As producer, I was actually having to look for places we could spend money. I had told the A&R person I could make the album for a tenth of our budget. He said, ‘Don’t ever say that. That’d ruin it for all of us.’”

An old-school musical maverick with a strong moral compass was now colliding head-on with the machinery of the music business. Those tensions would intensify during the making of Car Wheels on a Gravel Road.

Between February and March 1995, Williams and Morlix were back in Austin recording the album’s initial sessions. Williams, however, was unhappy with her vocals. “I was trying to grow,” she told Billboard in 2018, reflecting on the album’s 20th anniversary. “I didn’t want to make another Sweet Old World.”

Morlix saw it differently. Despite his reservations about the record’s production, he loved the sounds he’d achieved on Sweet Old World. “I was playing a Telecaster, through either a blackface Fender Twin, or a Vox Super Beatle head going into a Marshall 4x12 cabinet,” he says. “I have never heard a better-sounding and more versatile tremolo than on that Vox amp.”

I had told the A&R person I could make the album for a tenth of our budget. He said, ‘Don’t ever say that. That’d ruin it for all of us.’”

— Gurf Morlix

By his estimate, they’d completed nearly 90 percent of the album when Williams pulled the plug. She scrapped the sessions and relocated to Nashville, where she began spending time with guitarist and songwriter Steve Earle, who was close with producer Ray Kennedy. Before long, Williams asked Earle and Kennedy to re-record material she and Morlix had already tracked.

For Morlix, it was almost too much. He stepped down as producer and eventually walked away from Williams entirely, although he continued playing guitar as Car Wheels dragged on for the next three years.

“We were working on Car Wheels on a Gravel Road for forever and ever it seemed,” he says with a sigh. “She wasn’t feeling very good those days. The longer it went on, the worse it got.

“Making music is supposed to be joyful. What we were going through was not. Finally, it came to a head, and I quit.”

His exit coincided with Williams’ breakthrough. Car Wheels on a Gravel Road propelled her into the mainstream, powered by songs like “Metal Firecracker,” the Blaze Foley tribute “Drunken Angel,” the hip-hop-inflected “Joy” and the swaggering title track. The album reached number 65 on the Billboard 200, went Gold in the U.S., and was met with near-universal acclaim.

While Williams’ profile exploded, Morlix retreated.

“I didn’t pay much attention,” he insists. “It was all too fresh and raw.”

Commercial success changed nothing for him. “I learned that I can make great music with musicians I enjoy being around,” he says. “Getting out of that situation was the best move I’ve ever made.”

I learned that I can make great music with musicians I enjoy being around. Getting out of that situation was the best move I’ve ever made.”

— Gurf Morlix

Morlix believes he’s never been fully credited for his role in shaping Car Wheels. Some associated with the album have suggested little of his playing made the final cut.

“All I know is they had a lot of guitarists come in to try playing in place of me, and to add other parts,” he counters. “Every part I played got used in the final mixes. The person who mixed it told me the producer stressed that there were to be no politics involved in the mixing process.”

Even so, he remains ambivalent about his own work on the record.

“The parts I played on Car Wheels, all of which are used on the album, were done with my 1956 Gretsch Duo Jet electric through a blackface Fender Pro Reverb,” he recalls.

“But it wasn’t my amp. I wasn’t quite happy with the sounds we got. I had hoped to redo my parts, but things got dark, and I decided I’d had enough.”

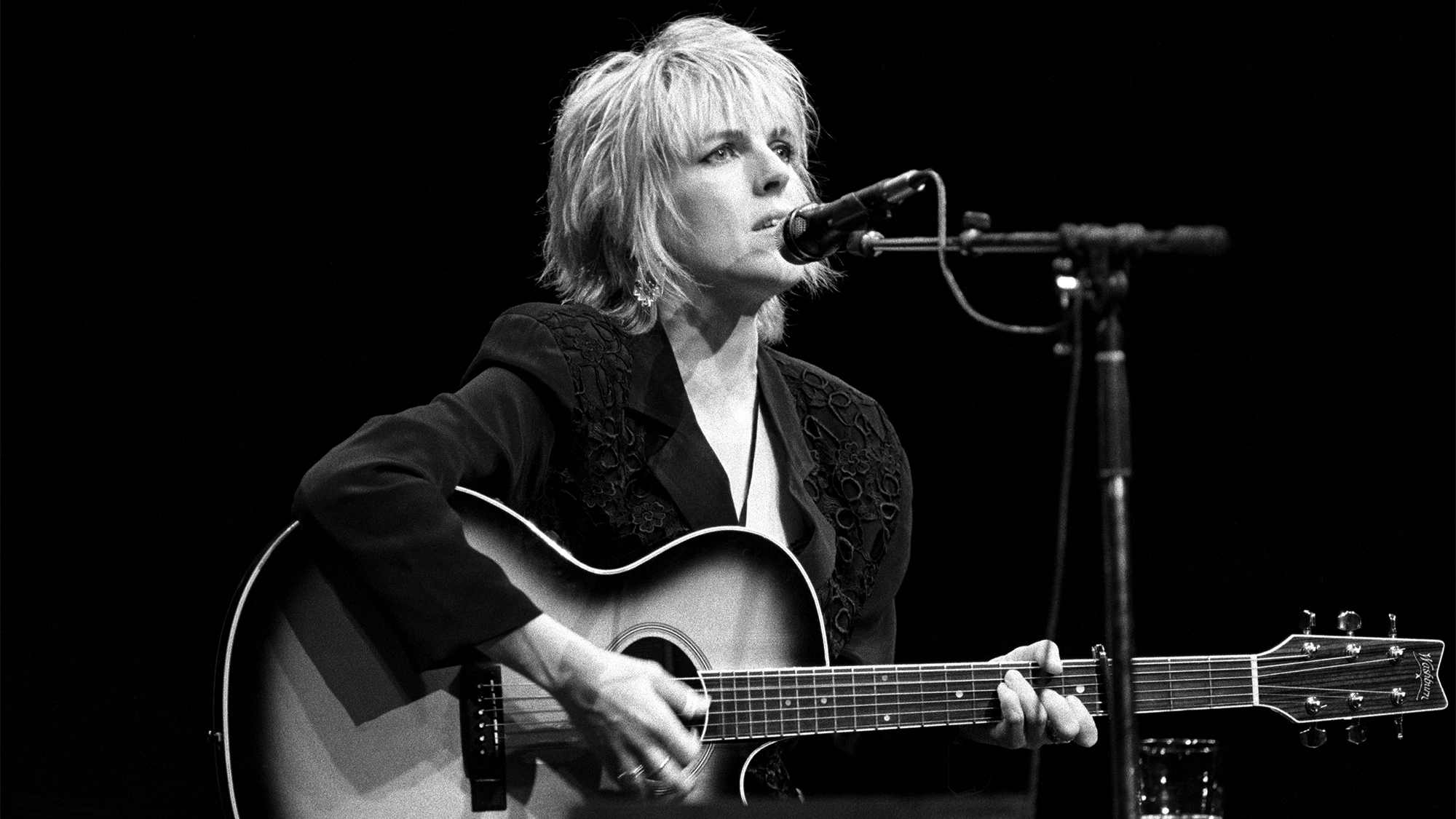

After leaving Williams’ band, the two artists diverged sharply. Morlix opted for a quieter path, focusing on his solo career and steering clear of the spotlight.

“I don’t have any regrets,” he says. “I did it all my way.

“I’ve turned down big money gigs with famous people ’cause I couldn’t see myself feeling good about having to play that music every night. And I’ve turned down offers from musicians I respect ‘cause the timing didn’t seem right, or something similar. I’ve been so lucky to be able to do what I do with no compromises.”

Listen closely to any Lucinda Williams album recorded since Car Wheels, and Morlix’s influence still lingers. The sonic vocabulary he helped establish remains baked into her music.

I do know that we were on the ground floor of Americana music. There were not many similar acts at the time.”

— Gurf Morlix

“I don’t really think about that,” Morlix says. “But I do know that we were on the ground floor of Americana music. There were not many similar acts at the time, but these days there are tens of thousands of people wanting to be part of it. It’s overwhelming.”

Morlix never left the music behind. Since stepping away from Williams, he’s released 19 solo albums, most recently 2025’s Bristlecone.

“Songwriting is not easy,” he says. “But it’s so rewarding when people tell you they are moved by a song you’ve written.”

He still plays daily and continues collecting gear. “I’ve got so many instruments and amps,” he says with a laugh. “I look at them as colors to paint with. My taste keeps evolving. I don’t play any better than I used to, but my desire to create keeps me moving.”

Andrew Daly is an iced-coffee-addicted, oddball Telecaster-playing, alfredo pasta-loving journalist from Long Island, NY, who, in addition to being a contributing writer for Guitar World, scribes for Rock Candy, Bass Player, Total Guitar, and Classic Rock History. Andrew has interviewed favorites like Ace Frehley, Johnny Marr, Vito Bratta, Bruce Kulick, Joe Perry, Brad Whitford, Rich Robinson, and Paul Stanley, while his all-time favorite (rhythm player), Keith Richards, continues to elude him.