“Music Is About Completing Those Little Circuits That Connect You to Your Past”: Mark Knopfler Looks Back on the Journey From “Sultans of Swing” to His Latest Solo Album, ‘Down the Road Wherever’

“It’s still about that, and it’s endlessly fascinating,” says the Dire Straits guitar legend

The following appeared in the September 2019 issue of Guitar Player.

“The landscape of guitar playing covers a massive geography for me,” Mark Knopfler says. “It goes all the way from Scotland into England and through the Delta, with important stops in a bunch of other places along the way. I like to think I’m bringing all those influences to bear every time I play. But when it comes to guitar – and, really, music in general – you truly only get to be a tiny part of it. It’s something that’s much, much bigger than you are.”

Humble words from a guy who has done it all: recorded massive hit records, written critically acclaimed soundtrack work and collaborated with heroes and contemporaries alike. Through it all, he has done something even rarer still: He’s secured a place on the Two-Note List – the unofficial roster of guitar players so identifiable and unique, most guitarists can pick them out after hearing them play just two notes. We all know who those players are, and Knopfler is one of them.

When Guitar Player spoke to the Dire Straits legend back in 2019, he was about to undertake a massive world tour in support of his latest solo album, 2018’s Down the Road Wherever (British Grove Records). At the time, Knopfler was looking forward to bringing his music to U.S. fans. “My songs are made to be performed live,” he told us. “I love the whole process of writing them alone and then recording them with the band, but ultimately the best part is playing them to an audience live. I enjoy the whole circus, traveling from town to town and interacting with this group of players is a total pleasure.”

And, of course, seeing Knopfler live onstage is the best way to experience his singular tone. It was “Sultans of Swing,” the first single from Dire Straits’ 1978 debut, that got it started. One of the Strattiest Strat tones of all time, Knopfler’s clean, bridge-and-middle pickup sound was created with a three-position switch on his ’61 Strat, with the selector crammed in a very Hendrix-approved, but anachronistic “in-between position.” (For the record, that bridge/middle sound on a Strat has been known since 1978 as either the "Knopfler Tone” or the “Sultans Tone.”)

The tune was plucked with his bare fingers, and it stood in stark contrast to the overdriven bombast of what was typical rock guitar at the time. As for its chords, fills and two burning solos, they showed the world that the young guitarist was the whole package: a deft rhythm player who could weave in funky answers to his vocal lines, and then peel off deep, memorable solos that combined bluesy pentatonics, liquid harmonic minor melodies and stunning arpeggiated figures, all the while singing profound lyrics that he wrote and never losing sense of the groove.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Welcome to the big leagues, Mark Knopfler! That didn’t take very long at all.

From there, Knopfler wrote more of the aforementioned hits, defined an era of MTV and found himself on the same stages as the biggest bands in the world – because his band was one of the biggest bands in the world. At that point, Knopfler wasn’t just a player – he was a seasoned, all-star veteran, a guy that people looked up to, and a musician that music fans expected to, you know, do some stuff.

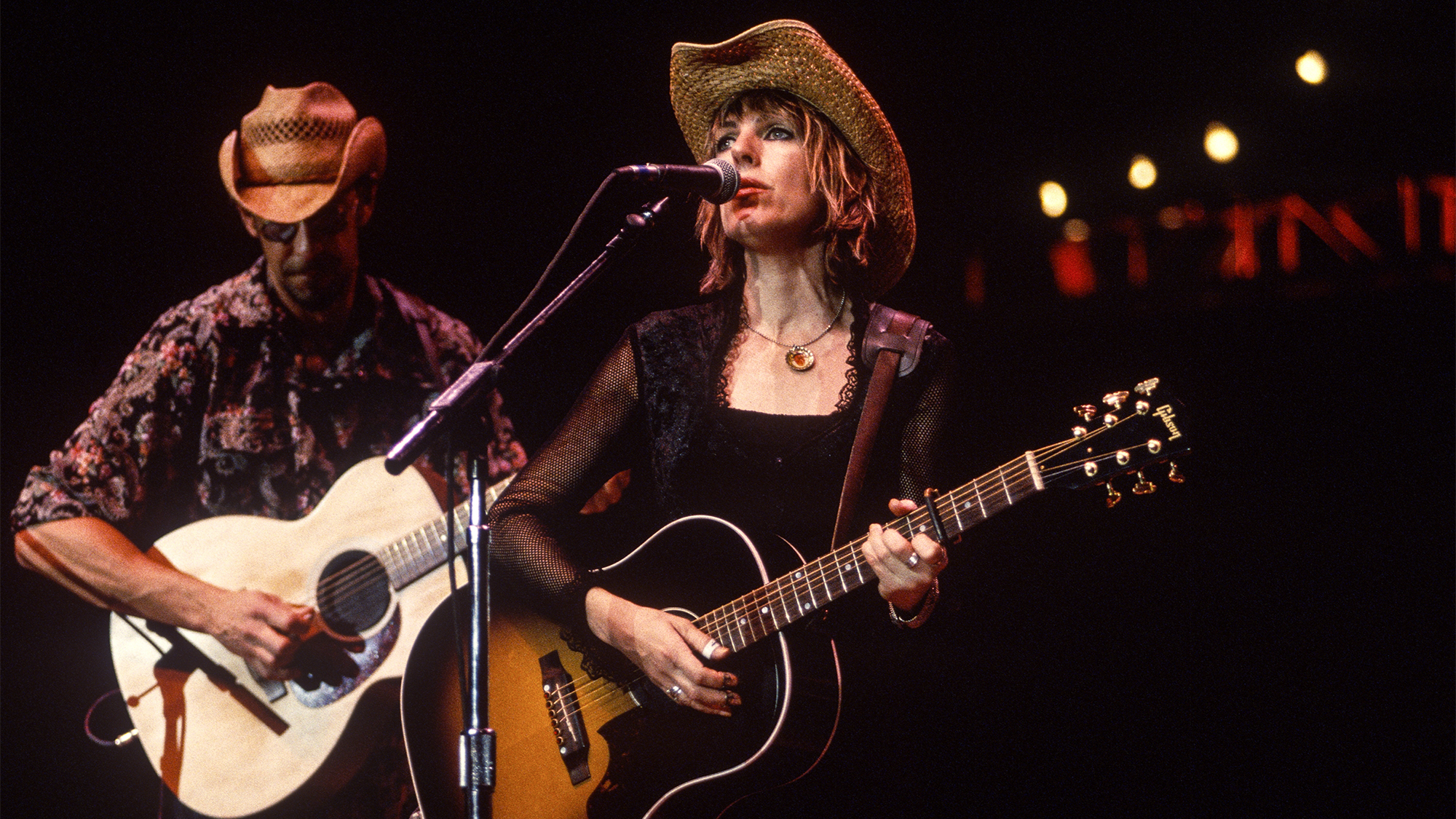

So what did he do? Over the next years, he produced records for two of his biggest heroes, namely Chet Atkins and Bob Dylan. He recorded soundtracks to films that would move and inspire generations of viewers. And he collaborated with artists like Emmylou Harris, Sonny Landreth, Eric Clapton, B.B. King, and many, many more. Along the way, he influenced scores of great guitarists in a bunch of different styles who didn’t sound like him but wished they could. He brought his awesome touch, tone, taste, and feel to the entire world, and he did it with all the dynamics, depth, and Knopfler-isciousness that he did as the young man who played guitar on a song called “Sultans of Swing.”

And he’s nowhere near done.

After dozens of albums and a boatload of awards, he keeps creating. Down the Road Wherever features 13 tracks of introspective writing fueled by his subtly powerful guitar stylings. Here, he speaks about the creation of the album, his take on distortion, and what it’s like to work with your heroes.

Your latest record opens with the tune “Trapper Man,” with a fingerpicked National that goes into a fairly heavy distorted electric guitar. Some people think those two tones couldn’t peacefully coexist in a song, but they do. You’ve always been good at sticking things in songs that “don’t belong” and making them work. Why do you think that is?

I suppose I’ve always done that, from an early age. You can think of “Brothers in Arms” as an accordion song, and I’m playing guitar across all of that stuff. When there’s Celtic music playing, I feel perfectly at home joining in on electric. And actually, the more power there is on the electric, the better it is for me, exactly because of that contrast you’re referring to.

I’m not really a fan of strict orthodoxy in anything. My bluegrass band would have bluegrass instruments, but then I’d play electric guitar, but I’d also be willing to play concrete mixer or machine tools. I don’t dig the folk police, or the tango police, or anyone who might turn around and say, “Well, that’s not the right lineup or instrumentation.” The bluegrass police might object to my concrete mixer, and I have no patience for that.

That’s been a hallmark of your career. Do you think it comes from the eclectic music that you’ve listened to in your life? Growing up, you had an equal love for blues, rock, rockabilly, country and more. Is that how you’ve struck down those barriers?

Yes, exactly, it is. I can remember playing in folk clubs, and there might be someone from the club who would say, “This is an English folk club. We don’t do American songs here.” And I thought that was absolute bullshit, because who knows if those songs were English or American anyway? Those songs have been across the Atlantic in both directions many times. Folk purists give me a pain.

Talk to me a little bit about “Just a Boy Away from Home,” from the new album. The tuning sounds like dropped C or open C.

It’s open C, and there’s quite a heavy set of strings on the guitar, which was an old ’60s Strat. I actually played that guitar on a bunch of songs in normal tuning on the Sailing to Philadelphia album [from 2000]. It just turned out to sound pretty nice with a slide on it, but then again a lot of guitars do. I think a lot of guitars are quite surprised to find themselves working out on slide.

You’re humble about your slide playing, but the fact is, you’re great at it. How do you play so beautifully in tune?

Oh, with difficulty.

How did you work your slide chops up?

Well, I started with the simple, straight-ahead stuff, like Elmore James. I think what happens is, when you go back that far, it adds a depth to your own playing. I also spent a lot of years playing country blues and acoustic blues on slide. Then I played with Sonny Landreth, and I love the way he plays. I’ve never actually asked Sonny to show me what he does, fretting behind the slide and all that. But then, a few years back, I just started doing it, and it sort of worked for me too.

Fingerpicking is a big part of it as well. It’s a combination of these little runs and moves, fretting behind the slide and picking with thumb and fingers.

What slides do you use?

I use Diamond slides. They can make them with pictures on the front of them, so I’ve got one with Chet Atkins and one with Elvis. One thing that’s interesting about them is that the hole is offset – it’s not in the center – so you can work with different thicknesses on the same slide.

Talk about the lead tone on “Back on the Dance Floor,” another great track from Down the Road Wherever. How was that tone created?

That would be probably the good old Les Paul-meets-Marshall. If it’s not that, it’s Les Paul meets Linda, which is a Komet that Ken Fischer made for me. Linda is very, very loud. A fantastic amp.

You’ve always been good at navigating loud, distorted sounds. You play very dynamically with massive tones that, depending on your touch, can seem almost clean and dirty at the same time. What do you look for in a dirty sound? How dirty is too dirty?

It’s a great question. I work on the dynamics in my sound, and it’s something I can’t do enough. Because once you overstep the gain, as opposed to the overall level, it squashes up too much and you lose all the dynamics.

That’s all that it is, really – a balancing act. Sometimes it’s played quietly, and sometimes it’s played more emphatically, and that’s part of the fun of it. You don’t need the faders on the board. It’s about getting a happening sound, and if you want to play a solo with that sound, you can if you lay into it.

Your solo on “Nobody Does That” has a really nice sense of composition, with a strong theme and variations on that theme. Was it composed or was that improvised?

That was a first take, the first time with the band. Then we edited sections together.

It’s an amazing band moment.

Everybody in the band is listening and reacting in real time. You can’t simply exist in your own bubble; that’s the kiss of death. You’ve got to be thinking about where you belong in the conversation, in that fabric.

All of these players are masters at being in the correct sonic range, not going into an area that’s being inhabited by someone else. And your first inclination to do something can be very, very valuable. That’s why first takes have often got that energy to them. They’ve got that relish, you know?

It’s definitely not what you’re most famous for, but you do occasionally play with a pick. You get a really beautiful sound on tunes like “Our Shangri-La.” What is your approach and what is your relationship with the plectrum?

I grew up loving Jimi Hendrix, and when I was playing Hendrix licks, it was quite fun for me to plug into a Bassman or a Marshall and play like that with a pick. But it sounded like somebody else, you know? I do love that sound, though. It doesn’t take very long before it all comes back to me.

Nowadays, if I have a song with those kinds of licks, I’ll probably do them with my fingers anyway. It’s just laziness really. I would always be losing picks. But I do love picks. I also love that sound where I’m playing a Strat or a Gretsch with a pick for the melody but using the whammy bar for the vibrato. You can’t get that sound any other way. That’s how I play all those lovely Hank Marvin Shadows tunes.

You can’t simply exist in your own bubble; that’s the kiss of death

Mark Knopfler

For a guy who is so closely associated with the Strat, you get some great Les Paul tones on this record. How do you set the controls?

One of the things that I like to do – and I did this on “Good On You Son” – is to use a Les Paul on the middle setting, but back off one of the levels just a bit, letting one pickup have predominance, and I might roll off the tone a little on one of them. The useful thing about a Les Paul is that you can make those little fine adjustments right on the guitar when you’re looking for the sound.

I’ve always got to remind myself to leave the guitar where it’s at if we’re going to go on a break. Quite often you pick up a guitar and just ram everything up all the way, and you’ll lose that sound. I have to remember not to touch the controls once I’ve found that special sound, that critical place where it’s doing what you want it to do. You’ll never get it back.

You’ve gotten to work with two of your biggest influences, Chet Atkins and Bob Dylan. Did you have moments where you thought, “If my 18-year-old self knew this day would come, he’d be pretty blown away”?

Absolutely. The thrill of being involved with music is about completing those little circuits that connect you to your past. That’s what it was all about. It’s still about that, and it’s endlessly fascinating.

Order Mark Knopfler’s latest solo album, Down the Road Wherever, here.