“I Wouldn’t Want to Go Through All That Again. It All Turned out Fine, Though”: Jeff Beck Reflects on a Life Devoted to Guitar

The legendary guitarist sat down for a chat and opened up before his 2009 Rock Hall honors and show-stopping all-star jam

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Jeff Beck was in Cleveland on April 4, 2009, to be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, on his own this time after going into the shrine as part of the Yardbirds 17 years prior. At that earlier ceremony, the Rock Hall’s seventh, Beck got attention for his memorable acceptance speech in which he acknowledged being tossed out of the band in 1966.

While his former bandmates, including Jimmy Page, looked on, Beck remarked, “Somebody told me I should be proud tonight, but I’m not, because they kicked me out. They did. Fuck them!” Fortunately, the smackdown was delivered in genial tones and received considerable laughter, and both Beck and Page were happily part of the night-ending all-star jam later on.

Beck was in fine fettle for his 2009 induction too, but palpably happier as he sat in the concierge lounge at the Ritz-Carlton hotel, post-rehearsal, with wife Sandra nearby and manager Harvey Goldsmith and photographer-friend Ross Halfin flitting in and out, preparing for the evening’s ceremony.

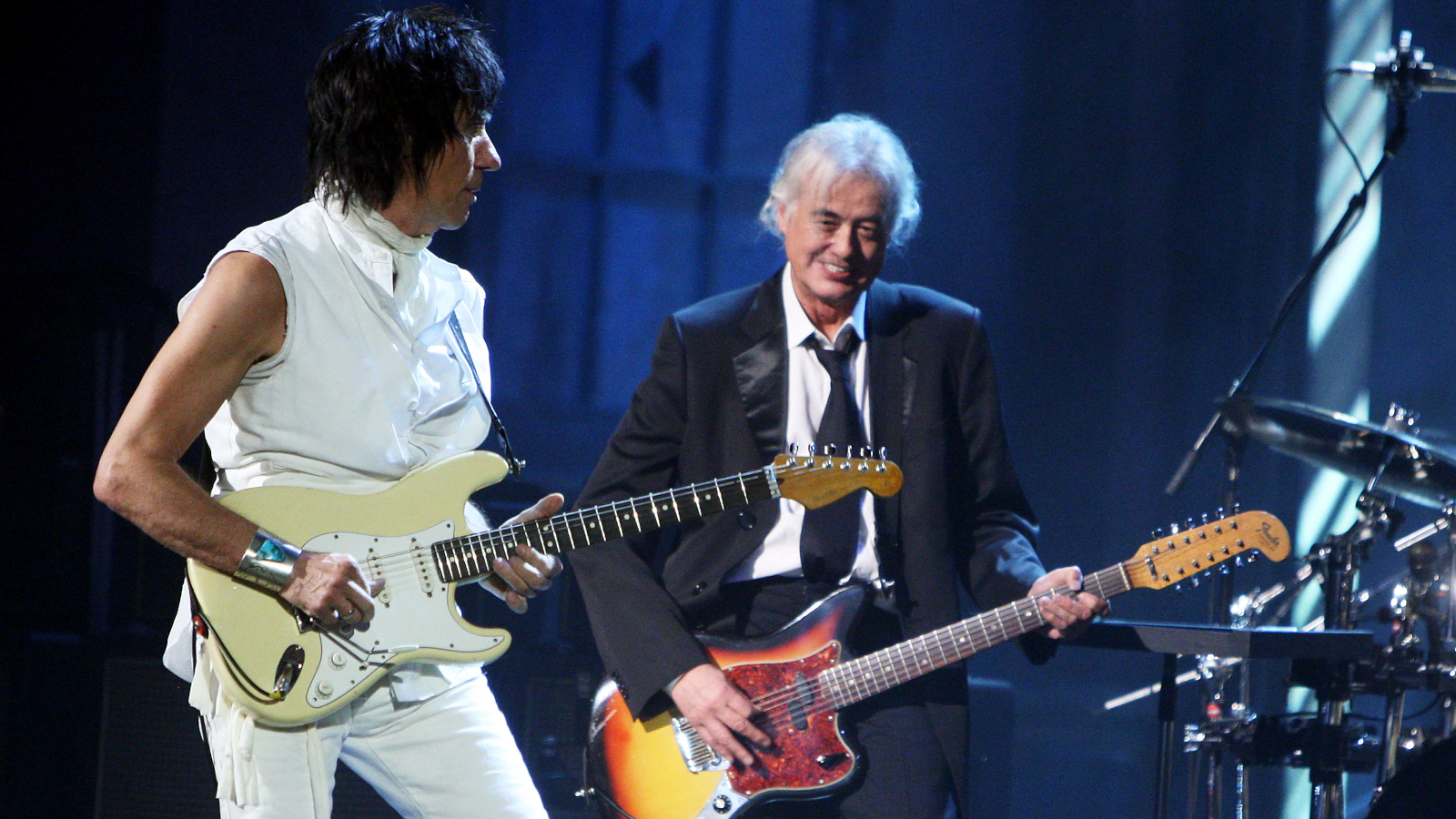

It turned out to be all sweetness and light – and fire once Beck strapped on his Stratocaster. Jimmy Page was on hand to make the induction speech, proclaiming that Beck “shifted the whole sound and face of electric guitar music. He’s been instrumental in pioneering a whole blueprint that was totally unique to him for everyone else to learn from.”

Page then joined Beck onstage to sandwich Led Zeppelin’s “Immigrant Song” inside “Beck’s Bolero” from the Jeff Beck Group’s 1968 debut, Truth. Beck also tore through Henry Mancini’s “Peter Gunn Theme,” then closed the night with an all-star jam that included Page, Ron Wood, Joe Perry, Red Hot Chili Peppers bassist Flea and Metallica’s Kirk Hammett and James Hetfield performing “The Train Kept A-Rollin’.”

The induction certainly came at a solid juncture in Beck’s career. His album, Live at Ronnie Scott’s (recorded during 2007 and released the following year) was a fan favorite, and earlier in the year he’d won his fifth Grammy Award for the live version of “A Day in the Life,” originally recorded for George Martin’s Beatles covers album In My Life 11 years prior.

Beck had also brought in Goldsmith, a legendary British concert promoter, to help raise his profile, which led to some of his most prolific touring to date, including shows with another friend, rival and former Yardbird Eric Clapton.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Fitting the moment, Beck was reflective as he sat down for a proper cuppa, further warming up for the festivities by talking about the events and particularly the mindset that had brought him to this point.

Your second induction into the Rock Hall – what does it mean to you?

Obviously I’m led to believe it’s a very worthy cause. [chuckles] But I’m very pleased. I mean, I guess if you are going to be recognized, this is the place to be recognized, and maybe the world at large will understand where I was going all these years. I’ve always got off the boat before they caught me, so now I’m a sitting target. [laughs]

You have indeed been something of a shape-shifter. Why the drive to do it that way?

Circumstances and sheer bloody-mindedness. What is that saying? “Listen to as much music as one human being can absorb with two ears, and then ask yourself, ‘What can I do with this?’” That’s what sends me on these journeys I’ve taken.

Is there a method to the madness, then?

I think mine always goes back to rhythm and blues, and it’s hugely triggered by listening to a record that you weren’t expecting to hear. Something would trigger the brain cells – nostalgia maybe – and you would pull off energy that came from there. And you appreciate all those fine players that have gone before, constantly referring to early blues, early jazz, Motown – anything that was quality – and then try to apply some of that wisdom to what you think you can do with a modern style of music.

There’s an interesting film clip at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame of a younger you commenting that he doesn’t know anything about music yet. Where are you on that path now?

I don’t know anything yet. [laughs] Ignorance is bliss, as far as musical terminology and musical theory go. If I don’t hear what I want, that’s the yardstick by which I measure goodness or suitability. I know when it’s wrong, and I am not really bound by any shackles of music. I just go. I really love that. Of course, I’d like to know what’s going on, but I think doing so by feel is good, and sometimes by ear.

Listen to as much music as one human being can absorb with two ears, and then ask yourself, ‘What can I do with this?’

Jeff Beck

Can you get to the point where you are satisfied with something?

Nope.

So do you drive yourself nuts?

[laughs] Yeah, because you think, Wow, I got this far with that; why didn’t we do better? I think you get mildly satisfied within a certain reason of time. I think, Oh, this is great, and I put it on the car radio just for kicks if it sounds really great.

But I never want to get too hung up on anything, because too many times, if you hear something, you’re gonna want to change it. It’s best left alone if you felt that was how it sounded best. Leave it. Go back to it six months later, or three months later, and listen to it. Press “random” and hear something you did three months earlier – that’s the best way to listen. That way you’re not willing it to be something it isn’t. You’ll hear it fresh, like everybody else is hearing it.

With what you know now as a musician, is there anything you’d like to go back to?

No, not really. There was BBA [Beck, Bogert & Appice], who I thought was fantastic. They were really rare, but unfortunately they didn’t have the material to keep the boat afloat. The playing was all there, and a three-piece to die for. It was like Cream – a bit more bold, but with less quality of songs, and that wasn’t a good recipe to continue.

Plus there was an Anglo-American management, which was tearing the money apart. One manager wouldn’t have this, and the other manager didn’t want that, and it just came to a financial dead end, really.

What led you to do music in the first place?

Well, my mum was playing piano when she was pregnant with me. That means my head was only a few inches away from the keyboard. They say you can hear inside the womb, so I guess I could hear what she was playing. And she was completely happy during my childhood to play on her own, and I’d just be sitting there, playing next to her or in a cradle listening to it. When you hear classy playing, it sinks in, I suppose.

Then, when I was about eight or nine, a friend of my dad played on the same piano, in the front room of my house, but he played Fats Waller. That’s what got me marveling at the difference. And the thrill of listening to my mum playing one minute and somebody transforming the sound of it into jazz piano got me trying to play it. And that’s how I got into it.

Those are some crucial influences that don’t often get talked about when people consider what you do.

Oh, sure. I think they think we’re born in a guitar shop somewhere and we only like Elvis or Gene Vincent. But music comes from everywhere – it might be one passing phrase on a classical piece that sticks with you. You might remember just a drum figure somewhere. In life’s musical jigsaw, you pick out these pieces and put your own music together.

What led you to guitar?

Just the fact that everyone was telling me about Elvis Presley. I didn’t ever have a TV set, but those little brats at school who were spoiled enough to have a TV, they told me – 1955 this was, I think – that, “You gotta see this guy Elvis. He plays the guitar,” and that’s when it became the most popular instrument.

In life’s musical jigsaw, you pick out these pieces and put your own music together

Jeff Beck

So Elvis was your guitar-hero portal?

That’s what got my attention, but I realized even back then that he wasn’t playing the guitar solos, because when you see him he’s strumming. I was clever enough to know that you don’t strum a solo, and that’s what started this quest to play detective and find out who played those amazing guitar solos in all the rock and roll records – the Gene Vincent records, the Elvis records. I’ve always been fascinated by the sound of solos on those records, the nature of the different sorts of sounds.

Buddy Holly was different than Scotty Moore. Scotty was different from James Burton. James was different from Cliff Gallup, and so it goes on. It was just a complete open season on whoever took your fancy. I had one record which I played over and over by Johnny Burnette and the Rock and Roll Trio. That record should be on a par with Elvis and never was. It was just a hillbilly rock album, fantastic stuff. And that’s all I wanted to be, playing that sort of music.

You became one of Les Paul’s “kids,” too.

He should’ve been president of the U.S., you know? He was a funny, warm, absolutely wonderful person.

You’ve played both Les Paul and Fender Stratocaster guitars during your career. How do they compare and contrast for you?

It’s a totally different animal. One is for very subtle and, I would say, more musical things that you can distract and abuse. You can’t do it with a Les Paul. It’s too delicate. It’s got a very delicate tone. Most people don’t ever realize that because they are plugged into monstrous amplifiers, which completely covers up the unique sound quality it has. All those years of development go straight out the window when you overload the amp. It could be a $500 piece of junk if you don’t know how to set it up.

Back to the past, did you consider music as a career early on.

Yeah, kind of to escape whatever proper job, I think, like many of the others. I don’t know if it was a calling. I was utterly, completely smitten with rock and roll. When your older sister comes over and buys a record player and puts Elvis Presley on and you’ve never heard anything like it on the radio, it’s an amazing thing. It’s the best toy ever. And then it ceases to be a toy and it becomes an obsession: listening. And then more records arrive, and more influences arrive. And that’s how my career was born, really.

My playing style was arrived through listening to records. In the ’50s it was Elvis, Gene Vincent, Little Richard… Everything that was in the charts in America we’d try to get ahold of, and it was almost like an under-the-counter job in the local record shop, because they were selling Pat Boone’s version of “Rip It Up” and didn’t have the Little Richard version. That, of course is a challenge to a schoolboy. He wants to hear the real deal. Like rap records today: They don’t want copies. They want the real thing.

You got to pay tribute to one of your key influences, Cliff Gallup, back on the [1993] Crazy Legs album.

Oh, I actually lived and breathed Cliff Gallup for a number of years. I never wanted to play anything else. As a matter of fact, all the bands I played with around ’59, ’60, I would play Cliff Gallup solos whether they were required or not.

Then I realized it was time to find my own style, and that came about just before the Yardbirds. The Yardbirds were a massive springboard in terms of free rein. They said, “What have you got in your box of tricks that can help us make a pop record?” and it was a challenge to come up with something for them that would make their records sound different. That was a wonderful challenge; instead of being told what to do, they asked me what I could come up with: “Come up with a riff and we’ll write the tune,” or “Here’s the lyric. What do you got for this?”

I would play Cliff Gallup solos whether they were required or not. Then I realized it was time to find my own style

Jeff Beck

It worked a treat until the road wore us out, really. That’s what it was. We weren’t prepared for world tours. We’d never gone outside of our home towns.

You famously slagged the Yardbirds off when the band was inducted into the Rock Hall. How do you look back on the band from this vantage point?

I think they treated me like shit. They paid me 20 pounds a week, and they depended on me just like they depended on Eric. That was something I only realized after they kicked me out, that, “Okay, they’ve got Jimmy, they don’t need me.” That wasn’t a very nice thing for them to do, so I was always a bit bitter about that.

They wouldn’t wait for me to recover from a horrible illness, which I thought was really nasty, and they found that Jimmy could hold the fort and they went to Australia and that was the end of it. I found Rod Stewart, and we went on from there. It’s just a ragged way of going about it

Between Jimmy Page at the Hall of Fame induction and your shows with Eric, you’ve been touching base with your past a bit in recent years. Does that at all change your perspective on that time?

Not really. It’s always a pleasure to look back, but I sort of shut my eyes and ears to the past when I left the Yardbirds – or, shall we say, I was forcibly removed. Then I went through a whole bunch of broken glass and barbed wire for a few years, and then there was Rod and all the rest of it. I wouldn’t want to go through all that again. It all turned out fine, though. Things seem to have evened out nicely.

Gary Graff is an award-winning Detroit-based music journalist and author who writes for a variety of print, online and broadcast outlets. He has written and collaborated on books about Alice Cooper, Neil Young, Bob Seger, Bruce Springsteen and Rock 'n' Roll Myths. He's also the founding editor of the award-winning MusicHound Essential Album Guide series and of the new 501 Essential Albums series. Graff is also a co-founder and co-producer of the annual Detroit Music Awards.