“The pressure was on. I got really lucky.” Jorma Kaukonen on how he forged the sound of psychedelic rock on Jefferson Airplane’s groundbreaking hit

Kaukonen was still making the transition from acoustic to electric guitar when he improvised his transformational solo

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Jorma Kaukonen has a vivid memory of recording “Somebody to Love,” Jefferson Airplane’s first hit single, in December 1966. A landmark of psychedelic rock, the song is inseparable from his guitar work. Yet when Kaukonen looks back on those sessions, his mind goes not to his own playing but to the voice that cut through the room, that of singer Grace Slick.

“I remember when I heard her — I was in the studio when she sang it,” he told Neely Tucker of the Library of Congress in an April 2024 interview. “And when she did that and we heard it back, it was like, ‘Wow!’

“But did we know that anybody outside of our little San Francisco group of pals would care about it? Absolutely not. Or I didn’t, anyway.”

As electrifying as Slick’s vocal performance is, she shares that sonic space with Kaukonen throughout the track. His sinuous riffing snakes between her phrases and coils beneath them like a menacing shadow. At its heart, “Somebody to Love” is a straightforward rock and roll tune. What make it “psychedelic” are Kaukonen’s exotic note bending and spectral tone, which render it hallucinatory.

When “Somebody to Love” was released in February 1967 as the second single from Jefferson Airplane’s Surrealistic Pillow, psychedelia was still coalescing. Earlier signals — the Yardbirds’ “Shapes of Things” and the Byrds’ “Eight Miles High,” both from 1966 — had pointed the way, but the genre wouldn’t ignite until the following year. Surrealistic Pillow helped light the fuse, yielding two defining hits: “Somebody to Love” and “White Rabbit.”

For Kaukonen, it was all uncharted territory. Before joining Jefferson Airplane in early 1966, he was an acoustic folk guitarist, playing clubs around Palo Alto and San Jose and living in the South Bay. Along the way he befriended Jerry Garcia and Bob Weir, future architects of the Grateful Dead. It was through that same scene that he met fellow guitarist Paul Kantner and singer Marty Balin.

“When Kantner and Marty Balin decided to put together an electric folk-rock band, Paul came to me,” Kaukonen recalled in Guitar Player’s June 1976 issue. “‘Hey look, we’ve got this band together. Why don’t you play guitar?’ I just sort of stood there and uttered, ‘Uh, well, I don’t know.’

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“You see, during that period I didn’t play electric guitar at all.”

His rig at the time was modest: a Gibson L-5 acoustic fitted with a pickup he’d bought for $60, paired with a Fender Princeton amp. Still, Kaukonen took the gig and soon recruited his bass-playing friend Jack Casady. He also gave the group its name — Jefferson Airplane — adapted from his own nickname, Blind Thomas Jefferson Airplane, a playful nod to acoustic blues legend Blind Lemon Jefferson.

He said, ‘Hey look, we’ve got this band together. Why don’t you play guitar?’ I just sort of stood there and uttered, ‘Uh, well, I don’t know.’

— Jorma Kaukonen

“All of a sudden I went from being an acoustic guitar player to learning how to play the electric guitar,” Kaukonen told Jas Obrecht in 1996. “I was given the opportunity for on-the-job training. And the spirit and everything was pretty much left up to us — you could play what you wanted to.”

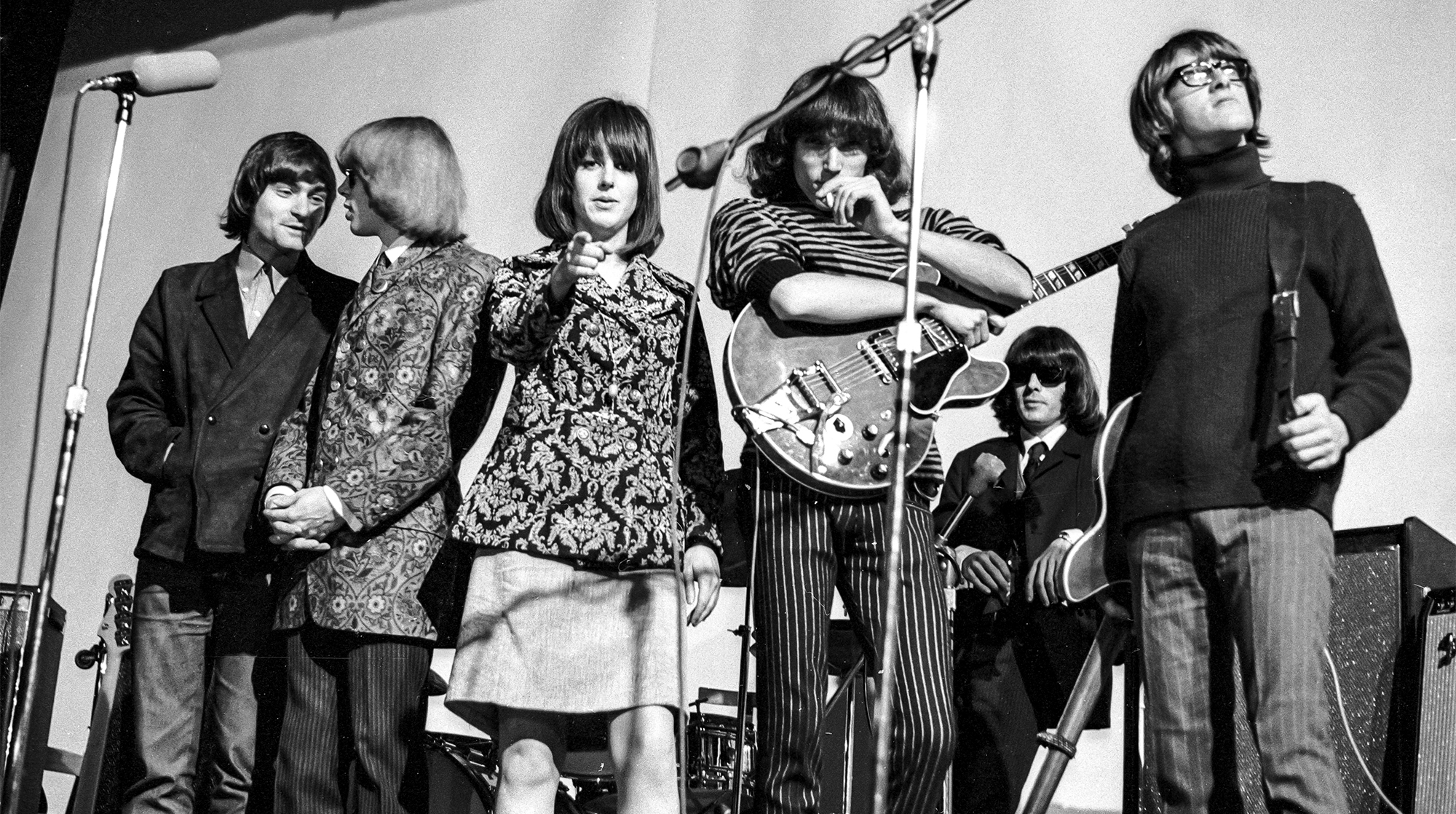

After the band’s folk-leaning debut, Jefferson Airplane Takes Off, the group pivoted hard toward rock on Surrealistic Pillow, their first album with Slick. She’d arrived from the Great Society, one of San Francisco’s earliest psychedelic outfits, where she performed alongside her husband and his brother, Darby Slick.

It was Darby who wrote “Somebody to Love,” originally titled “Someone to Love,” as a bitter farewell to a departing girlfriend. Released by the Great Society in February 1966, the single went nowhere. By October, Grace had joined Jefferson Airplane, bringing the song — along with her own “White Rabbit” — into RCA Studios at 6363 Sunset Boulevard in Hollywood.

“It was a huge studio where they did symphony orchestras,” Kaukonen told Tucker. “They had us sitting in the middle, with gobos [acoustic partitions] to isolate us as much as possible.”

The technology was primitive by modern standards. “Three-track machines, no noise reduction,” Kaukonen recalled to Obrecht. Performances were essentially live, with minimal overdubs. As he put it, Surrealistic Pillow “is as close to a live album in the studio as you’re ever going to get.”

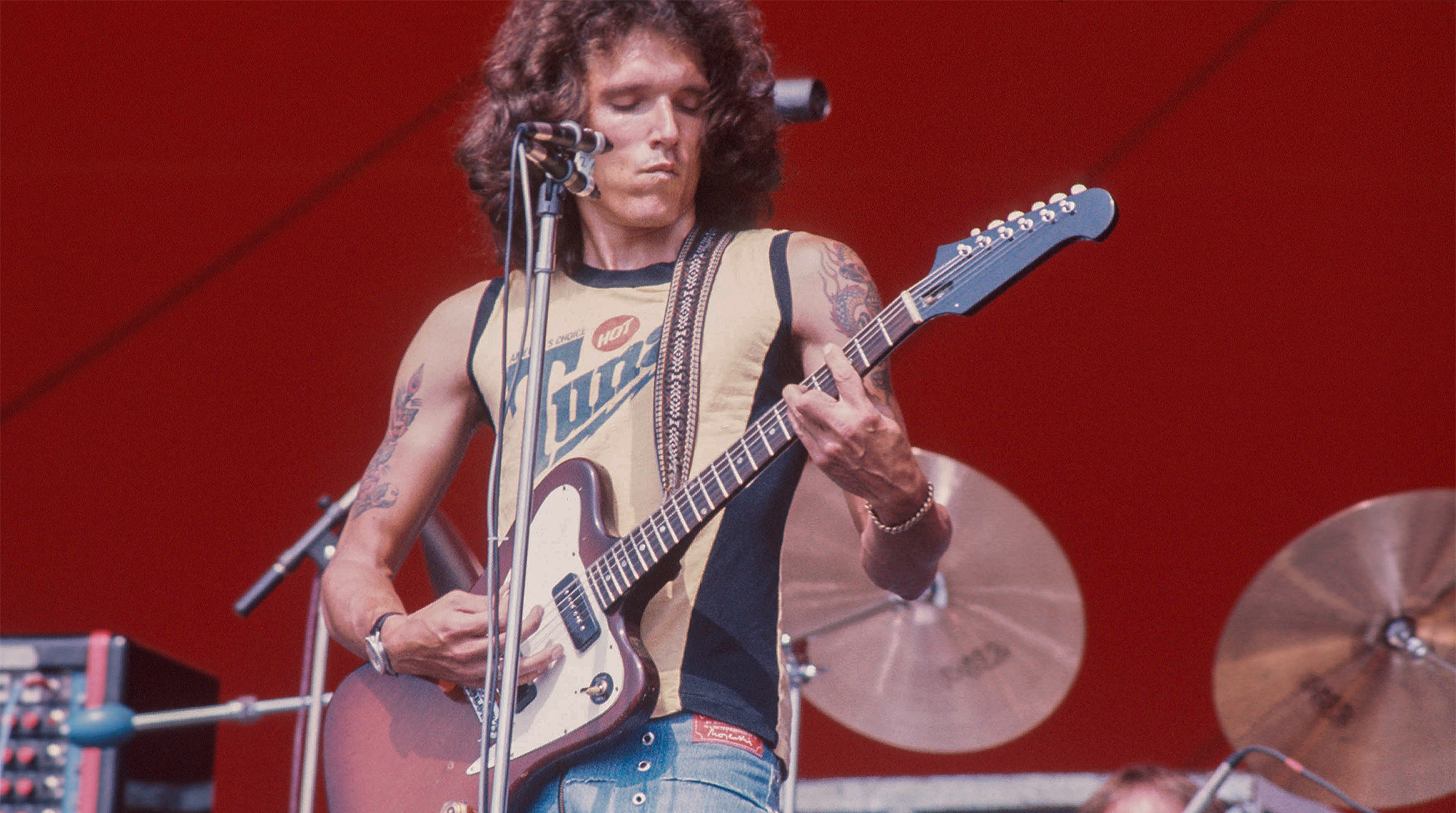

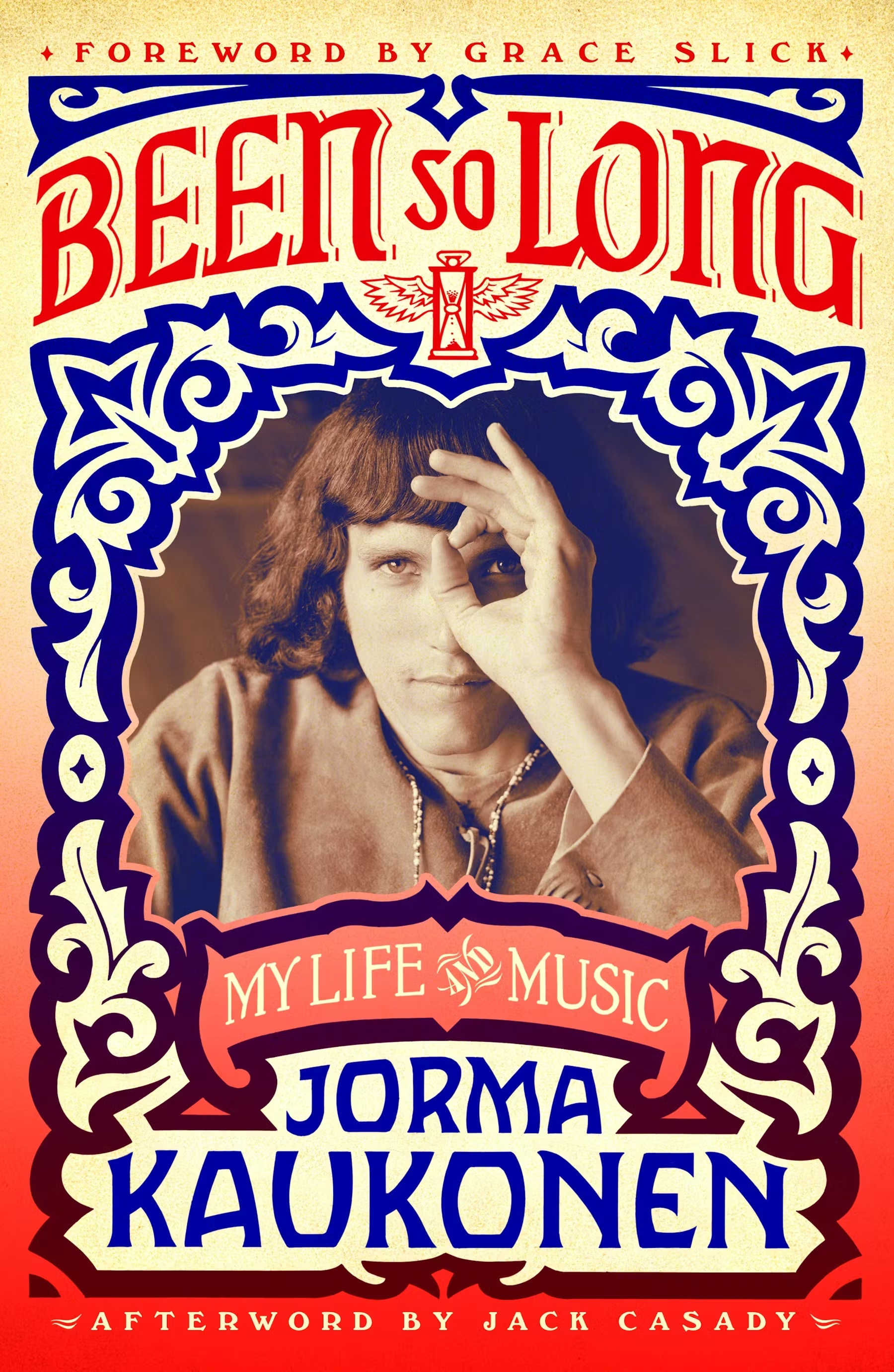

“Around the time of Pillow I was transitioning from the Guild Thunderbird guitar and the Standel amp to the Gibson and two Fender Twin Reverbs, but I was still waffling between two setups. The solos on ‘White Rabbit’ and ‘Somebody to Love’ were done with the Thunderbird and the Standel (minus the horns [Kaukonen had added an upholstered box from Kustom with two high-frequency horns]). Saturating the sound with spring reverb was the deal. The other tracks were done with the Twins and the ES-345 Stereo.” — Jorma Kaukonen in his autobiography Been So Long: My Life and Music.

Kaukonen’s gear on “Somebody to Love” was equally unorthodox: a Guild Thunderbird electric guitar and a Standel Super Imperial combo with two 15-inch speakers. “I got it because the Lovin’ Spoonful guys had one,” he told Tucker of the amp. “Solid-state. And a Guild Thunderbird guitar — nobody would play any of these instruments today.

“So here’s this solid-state amp and this odd Guild guitar, and that’s the sound of those solo guitars on ‘Somebody to Love’ and ‘White Rabbit.’”

In retrospect, he shrugs at the fetishization of equipment. “Guys like me, guitar players, we geek out about gear all the time,” he said. “But back in those days, you just played whatever you got.”

Solid-state. And a Guild Thunderbird guitar — nobody would play any of these instruments today.”

— Jorma Kaukonen

That same looseness defined his solos. Nothing was mapped out in advance. “We’d rehearsed the songs, but once you’re in the studio and play it, then it lives forever,” he explained. “We just kind of went for it.”

The result is a solo pulled from thin air. Opening with three piercing, high-register wails, Kaukonen winds along through the Dorian mode before ending on a phrase that defies resolution, leaving the song suspended in midair. He once dismissed his accomplishment as a “moderately psychedelic solo,” but its serpentine melody and cutting tone — at times sounding almost as if recorded backward — became defining traits of the psych-rock genre.

Kaukonen remained baffled by it years later. “People say, ‘How did you figure that out?’” he told Obrecht. “And my answer is, ‘I didn’t know any better.’ I just dicked around until that came out.”

Asked again by Forbes in 2016, he was no closer to an explanation. “The answer is, I wish I knew. I’d do it all the time,” he said. “People say, ‘What pedal did you use?’ Pedals didn’t exist back then! The pressure was on. I got really lucky.”

Released in February 1967, “Somebody to Love” climbed to number.five on the U.S. charts and hit number one in Canada, helping usher in the Summer of Love and transforming Jefferson Airplane into standard-bearers of the San Francisco sound.

Yet Kaukonen draws a line between the song’s legacy and the band’s true psychedelic awakening, which he locates on their next album, After Bathing at Baxter’s.

“In my opinion today, the psychedelic Jefferson Airplane album would be Baxter’s,” he told Obrecht. “That’s where we really started to stretch out.”

Christopher Scapelliti is editor-in-chief of GuitarPlayer.com and the former editor of Guitar Player, the world’s longest-running guitar magazine, founded in 1967. In his extensive career, he has authored in-depth interviews with such guitarists as Pete Townshend, Slash, Billy Corgan, Jack White, Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren, and audio professionals including Beatles engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott. He is the co-author of Guitar Aficionado: The Collections: The Most Famous, Rare, and Valuable Guitars in the World, a founding editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine, and a former editor with Guitar World, Guitar for the Practicing Musician and Maximum Guitar. Apart from guitars, he maintains a collection of more than 30 vintage analog synthesizers.