“I wanted Eric for a bit of moral support. I think it was the same reason he asked me to play on that session.” George Harrison on the time Eric Clapton asked for a little help from his friend

The two guitarists were growing closer as friends and musicians when they leaned on the other for assistance

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

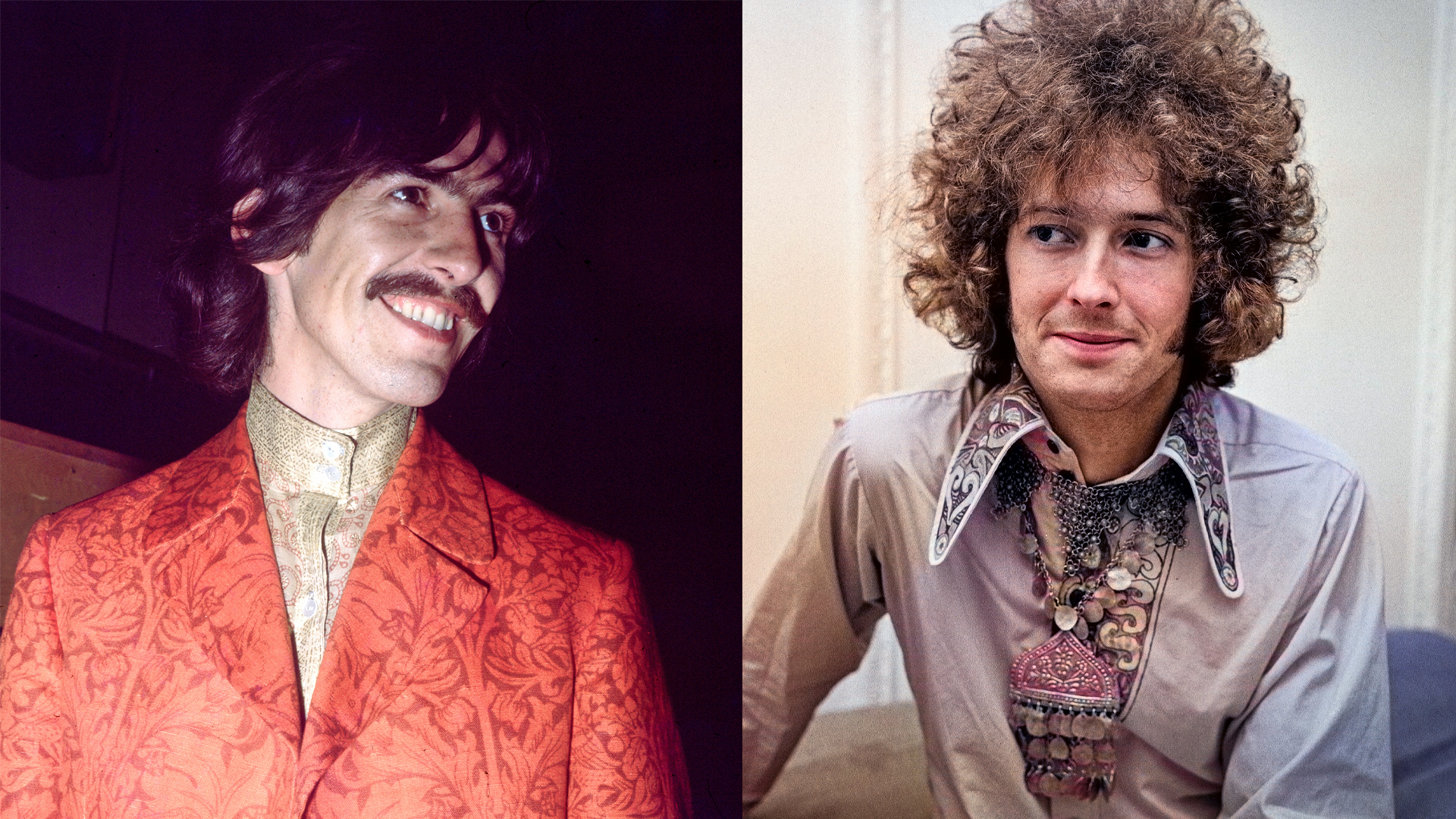

How Eric Clapton came to perform on “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” is one of the most retold stories in Beatles lore. Frustrated by his bandmates’ indifference to the song, George Harrison invited his close friend Clapton into the studio, partly for moral support and partly to ensure the Beatles took the session seriously.

But as Harrison revealed in a 1987 Guitar Player interview, that historic collaboration quickly became reciprocal. Just weeks after the September 6, 1968, Beatles session, Clapton asked Harrison to return the favor on what would become Cream’s final studio album.

Since forming in 1966, Cream had risen to the summit of hard rock, revered for their blues-rooted psychedelia and the virtuosity of its members. Yet internal tensions — particularly between bassist Jack Bruce and drummer Ginger Baker — had eroded the group’s stability. By May 1968, while touring the United States, the band decided to break up. Recordings from that tour, including their definitive live version of “Crossroads,” appeared later that year on Wheels of Fire.

Running largely on fumes, Cream embarked on a brief farewell tour from October 4 to November 4, before closing the book with two final concerts at London’s Royal Albert Hall on November 25 and 26. In the weeks between the tour and those last performances, the band convened at Wally Heider Studios in Los Angeles to record three new songs. The concept was simple: each member would contribute one original tune, with the three studio tracks supplemented by live recordings to complete the album.

Clapton, however, was stuck. Restless with Cream’s extended solos and psychedelic excess, he was searching for a new musical direction and struggling to find a song that fit. Earlier that year, both he and Harrison had fallen under the spell of the Band’s earthy, understated approach.

They were particularly drawn to guitarist Robbie Robertson, whose work with the Hawks — Bob Dylan’s backing band during his controversial 1965 electric tour — and later on Music from Big Pink offered a blueprint for something more grounded.

Clapton had managed to get hold of rough mixes from Dylan and the Band’s Woodstock sessions and found them revelatory.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“I got the tapes of Music from Big Pink and I thought, well, this is what I want to play — not extended solos and maestro bullshit, but just good funky songs,” he said in Conversations with Eric Clapton.

To help him make that pivot, Clapton turned to Harrison, who happened to be in Los Angeles producing Jackie Lomax’s debut album, Is This What You Want?

I got the tapes of ‘Music from Big Pink’ and I thought, well, this is what I want to play — not extended solos and maestro bullshit, but just good funky songs.”

— Eric Clapton

“He called me up and said, ‘Look, we’re doing this last album, and we’ve each got to have our song by Monday,’” Harrison recalled to Guitar Player editor-at-large Dan Forte

“I finished the verses off, and he had the middle bit already, and I think I wrote most of the words to the whole song—although he was there, and we bounced off of each other.”

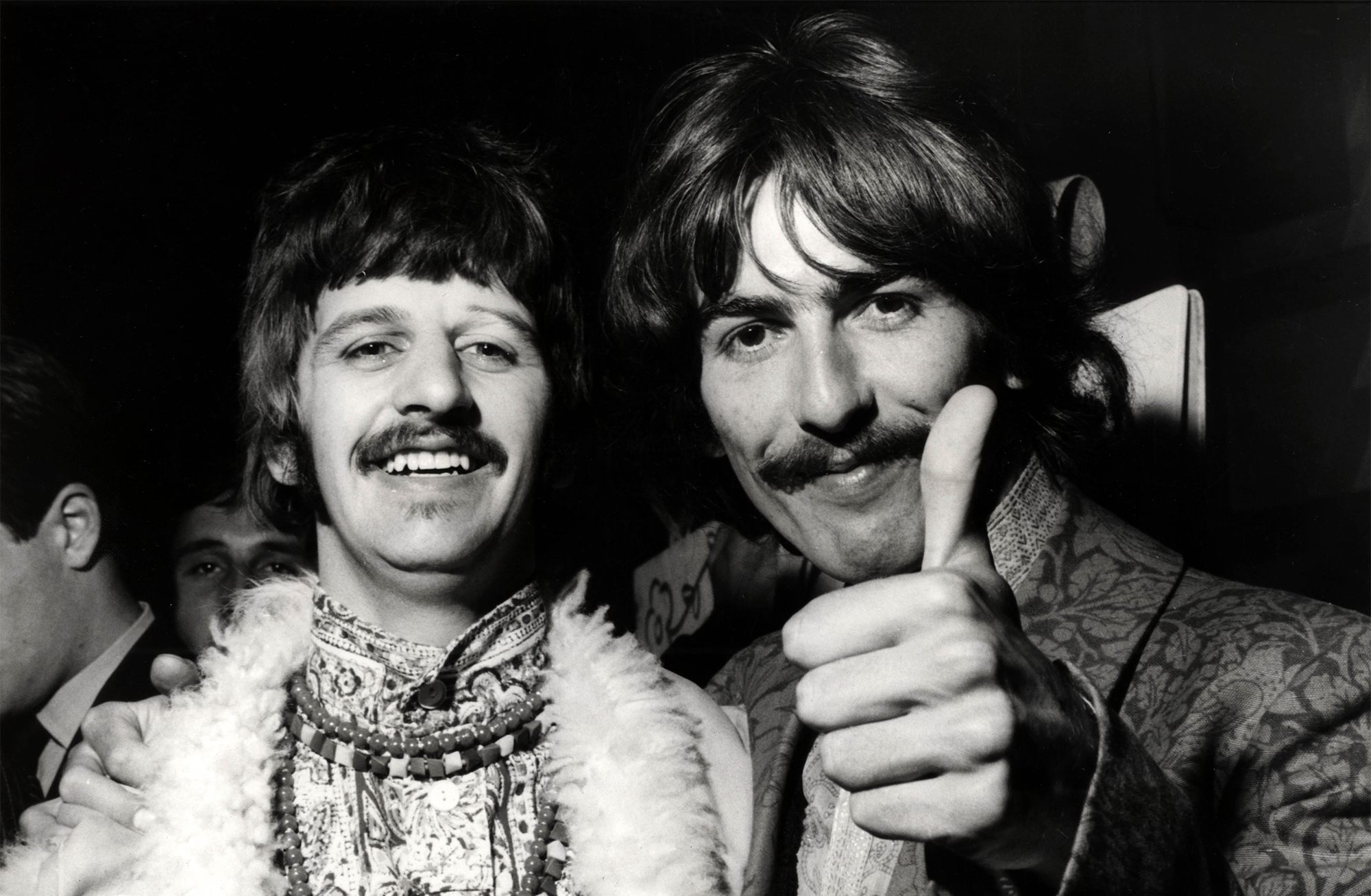

Harrison later added that Ringo Starr contributed a single, memorable line. “Ringo walked in drunk and gave us that line about the swans living in the park,” Harrison said in another interview. Since Starr wasn’t in Los Angeles at the time, it’s likely his contribution came during overdubs recorded a month later at IBC Studios in London.

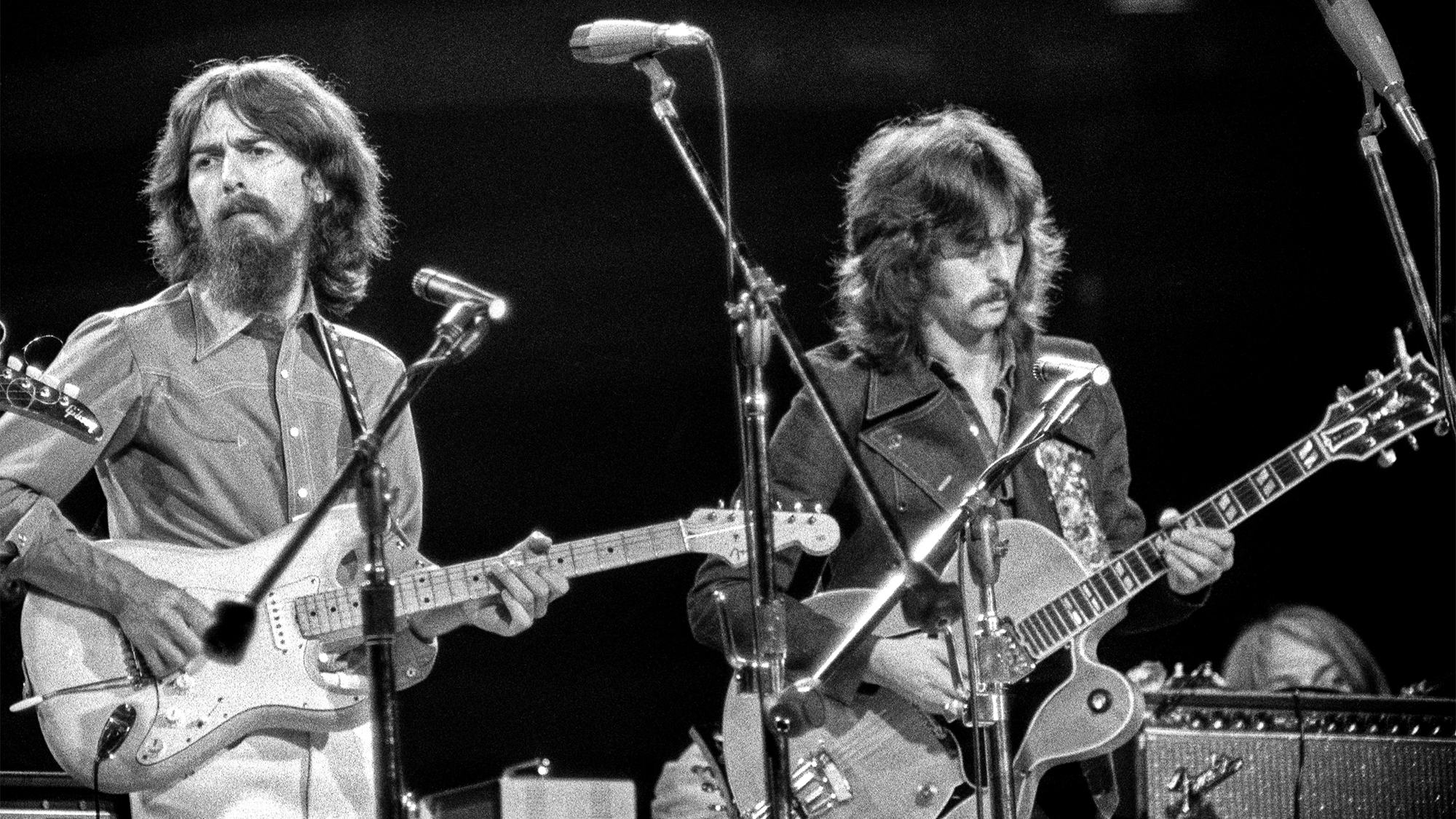

The initial session was stripped-down and collaborative. Harrison played rhythm guitar, producer Felix Pappalardi handled piano, and Bruce and Baker supplied the rhythm section. Clapton performed the lead electric guitar parts using his the cherry red Gibson ES-335 semihollow he purchased in 1964, playing it through a rotary speaker cabinet. Some accounts claim he used a Fender Vibratone. Although Harrison said it was a Leslie, he may have been using the name generically.

We played the song right up to the bridge, at which point Eric came in on the guitar with the Leslie.”

— George Harrison

“We played the song right up to the bridge,” he recalled, “at which point Eric came in on the guitar with the Leslie. And then he overdubbed the solo later.”

The song’s title, meanwhile, emerged from a now-legendary misunderstanding.

“The story’s getting a bit tired now,” Harrison admitted, “but I was writing the words down, and when we came to the middle bit I wrote ‘Bridge.’ And from where he was sitting, opposite me, he looked and said, ‘What’s that — ‘Badge’?’ So he called it ‘Badge’ because it made him laugh.”

In retrospect, Harrison believed Clapton reached out for the same reason he had invited him into the Beatles’ orbit weeks earlier.

“I wanted Eric on ‘My Guitar Gently Weeps’ for a bit of moral support and to make the others behave,” Harrison said, “and I think it was the same reason he asked me to play on that session with them.”

For contractual reasons, Harrison was credited on Goodbye under the pseudonym L’Angelo Misterioso, though his involvement quickly became known in the music press. Early U.K. pressings of the album credited both Clapton and Harrison as co-writers, while the original U.S. release listed Clapton alone.

Although its opaque lyrics have more in common with the stream-of-consciousness style found on psychedelic tunes of the time, “Badge” is musically to the point, built around a concise structure that contrasts sharply with its swirling, otherworldly guitar solo. Clapton would revisit that same dynamic the following year with “Presence of the Lord,” his lone songwriting contribution to his next band, Blind Faith, and a clear signal that he was leaving Cream’s excesses behind.

Christopher Scapelliti is editor-in-chief of GuitarPlayer.com and the former editor of Guitar Player, the world’s longest-running guitar magazine, founded in 1967. In his extensive career, he has authored in-depth interviews with such guitarists as Pete Townshend, Slash, Billy Corgan, Jack White, Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren, and audio professionals including Beatles engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott. He is the co-author of Guitar Aficionado: The Collections: The Most Famous, Rare, and Valuable Guitars in the World, a founding editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine, and a former editor with Guitar World, Guitar for the Practicing Musician and Maximum Guitar. Apart from guitars, he maintains a collection of more than 30 vintage analog synthesizers.