"I Kept Trying to Use Other Guitars, but Nigel Godrich Would Say, ‘You Know What We Should Try, Don’t You?’ ‘Casino?’ ‘Yep!’": Paul McCartney Reveals How He Fell Back in Love with His Epiphone Casino, and Transformed His Sound, in 2005 GP Interview

For the critically acclaimed 'Chaos and Creation in the Backyard,' McCartney was encouraged to abandon his Les Paul, but also found time to beef up his acoustic fingerpicking, and plug into his old Vox AC30.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

This article originally appeared in the November 2005 issue of Guitar Player.

If you were lucky enough to be Paul McCartney in 2005, how the hell would you approach a new album? Would you avoid competing with your legend, and just coast on your rep? Would you pitch and churn in a vortex of option anxiety, knowing that you could easily write fabulous pop songs, kick-ass rockers, soaring ballads, cinematic underscores, or even a classical concerto? Are you even excited about being a musician anymore?

Hell, you’ve been dragging yourself to recording studios, concert stages, television and movie facilities, charity events, and other celebrity functions for more than 40 years. You’ve seen it all, you’ve done it all, you’ve gotten tremendously rich, and you’re a “Sir“ for crying out loud! What could possibly still be driving you to sit all alone in a quiet room waiting for inspiration to boil up into your imagination? Well, who knows what your bogus McCartney reasons might be, but for the authentic and genuine Sir Paul, it’s all about love.

Yep. That simultaneously goofy and deadly serious word that slithers its way through literature, movies, and countless Beatles songs. Paul McCartney still loves making music. And it ain’t just talk, luv. This September, the 63-year-old former Fab released his 20th post-Beatle album, Chaos and Creation in the Backyard, and launched his fastest-ever selling U.S. solo tour (some dates sold out in less than 20 minutes).

Chaos was recorded in London and Los Angeles during a two-year period with Radiohead and Beck producer Nigel Godrich, who was recommended by McCartney’s long-time studio main man, George Martin. (The legendary Sir George, who famously shepherded the Beatles, and whose recording career spans back to the direct-to-lacquer days, obviously listens to rock radio!)

And lest you think McCartney has reached a point of artistic complacency, he remains passionate enough about his musical children to fight for their lives, as was the case when Godrich expressed disappointment in “Riding to Vanity Fair,” and suggested that the song be left off the album. He also agreed to play most of the instruments on the album after Godrich expressed a desire to cop a McCartney vibe (McCartney’s 1970 solo album where he famously tracked almost all the instruments himself at his home studio).

“Nigel had a clear idea of the record he wanted to make,“ explains McCartney, “and he started off by saying, ‘I want to make a record that’s you.’ We worked a week with my live band, but Nigel decided to take the approach of me playing most of the parts. ‘I’d like to hear you play drums,’ he’d say. So I talked to my band about it, and they said it was no problem if they didn’t play on the album. They were into whatever it took to make a good record, and they said they’d be happy to play the tracks live.“

So what happens when one of classic rock’s most astounding talents is guided by one of modern rock’s most cutting-edge production visionaries? Well, in a cagey sabotage of expectations, the culmination of the McCartney/Godrich collaboration is a spectacle of stark, exquisite simplicity.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Godrich directed an extremely organic and uncluttered sonic spectrum for Chaos. As a result, every instrument stands out like a sentry, and supports McCartney’s still-beautiful and beguiling melodies. Nothing is wasted. Nothing is superfluous. There are no obvious production tricks, nor any bizarre effects or textures presented simply because they might sound hip for the next 15 minutes.

All you get on the introspective Chaos is one astounding voice, 13 fantastic songs, a collection of evocative instrumental performances, and a heart full of good feelings.

Going into pre-production for the album, was it a surprise that Nigel wanted to pursue a very simple and natural approach – one that almost brought you back to the unfussy charm of your first solo album?

“It really did sneak up on me, but I figured that we were looking for some sort of direction, and it was good to get Nigel to make some of the key decisions. He definitely wanted to present the whole thing straight from the shoulder, and just document some good songs, some good singing, and some good playing.

“Once I caught onto his plan, I realized that it was good. We’d done this sort of thing in the Beatles. It was either Revolver or Rubber Soul – I can’t remember which – where we outlawed echo to keep everything dry and really in your face. It just presented everything right there with no added cosmetics.

In the ’60s, when the Beatles were quite experimental, we’d say to Ringo, 'Aw, man, didn’t you use that snare drum on the last track? Let’s not use it. Let’s get out a packing case, or hit the back of a chair or something'

“For my part, my main contributions were the songs. I would bring in a tune, and if he didn’t like it, he’d just say, 'I’d rather not work on that one. What else have you got?' He was pretty tough, and at first I thought, 'Dear me, I’m not going to like this guy.' But, in actual fact, I respected his decisions – although there were a couple of songs that I fought for.“

For example?

“'Riding to Vanity Fair' is the main example. He wasn’t too keen on the first version of that song, but I could see something in there. I said, 'I’m not sure you’re right about this one, Nigel.' I didn’t quite understand what he didn’t like, so I said, 'Look, we’re going to make this work.' But up until a few weeks before we completed the album, the song still hadn’t made it. Eventually, I sat him down and asked, 'Tell me exactly what you don’t like about this.'

“We went through it line by line, and we ended up completely rewriting the melody. It used to be much brighter, but Nigel thought it was too chirpy. So we took it to a different place by inserting a more moody melody in the second and third lines. That changed the nature of the song – I mean, we pretty much rewrote it – and it finally made the album.“

How did you approach the “Paul plays it all” tracks?

“It might be piano, guitar, bass, drums – that kind of order. But it varied every time, really. It came down to whatever we fancied, and if Nigel thought something was missing, we’d add a part later on. Some of the songs are very sparse on the drums, for example, and Nigel would sometimes add percussion to fill out parts. On 'How Kind of You' and 'Friends to Go' most of the song is just a bass drum. We didn’t bring in the whole kit until near the end of the song.“

That reminds me of when you played drums on the Wings album, Band on the Run. You also didn’t use the entire kit for some of those songs – which kind of weirded me out at the time – but those tunes still rocked.

“I’ve always thought it was an interesting approach to go for something unconventional regarding drums and rhythm tracks. In the ’60s, when the Beatles were quite experimental, we’d say to Ringo, 'Aw, man, didn’t you use that snare drum on the last track? Let’s not use it. Let’s get out a packing case, or hit the back of a chair or something.' But then things got sort of boring – a bit more straightforward – in the middle of the ’70s.

“People would get a proper drum kit, and play traditional drums throughout a song, and you just had to be clever with the musical arrangements. I told Nigel, 'We’d also do things like playing tambourine on a chorus, stopping it for the verse in favor of handclaps or something, and then bringing in the tambourine again on the next chorus.' That way, you got the feeling of light and shade, and we did a lot of that on this record.

“The more you listen to it, the more you’ll hear how things have been placed very carefully, yet they achieve the effect that we haven’t even thought about them. We tried to make it seem effortless. There are quite a few nice little layers on the record – colors that Nigel thought would fit sonically within a song without calling attention to themselves. As a result, I think the album sounds very earthy.“

How did you develop your guitar parts for the album?

“'Organic' was a word that came up quite a bit as we were working. I would normally track a song using the instrument I wrote it on. For example, 'Friends to Go' was written on my Martin, so I started there, and just sang the song.“

There are also some very beautiful and subtle electric guitar layers on that song.

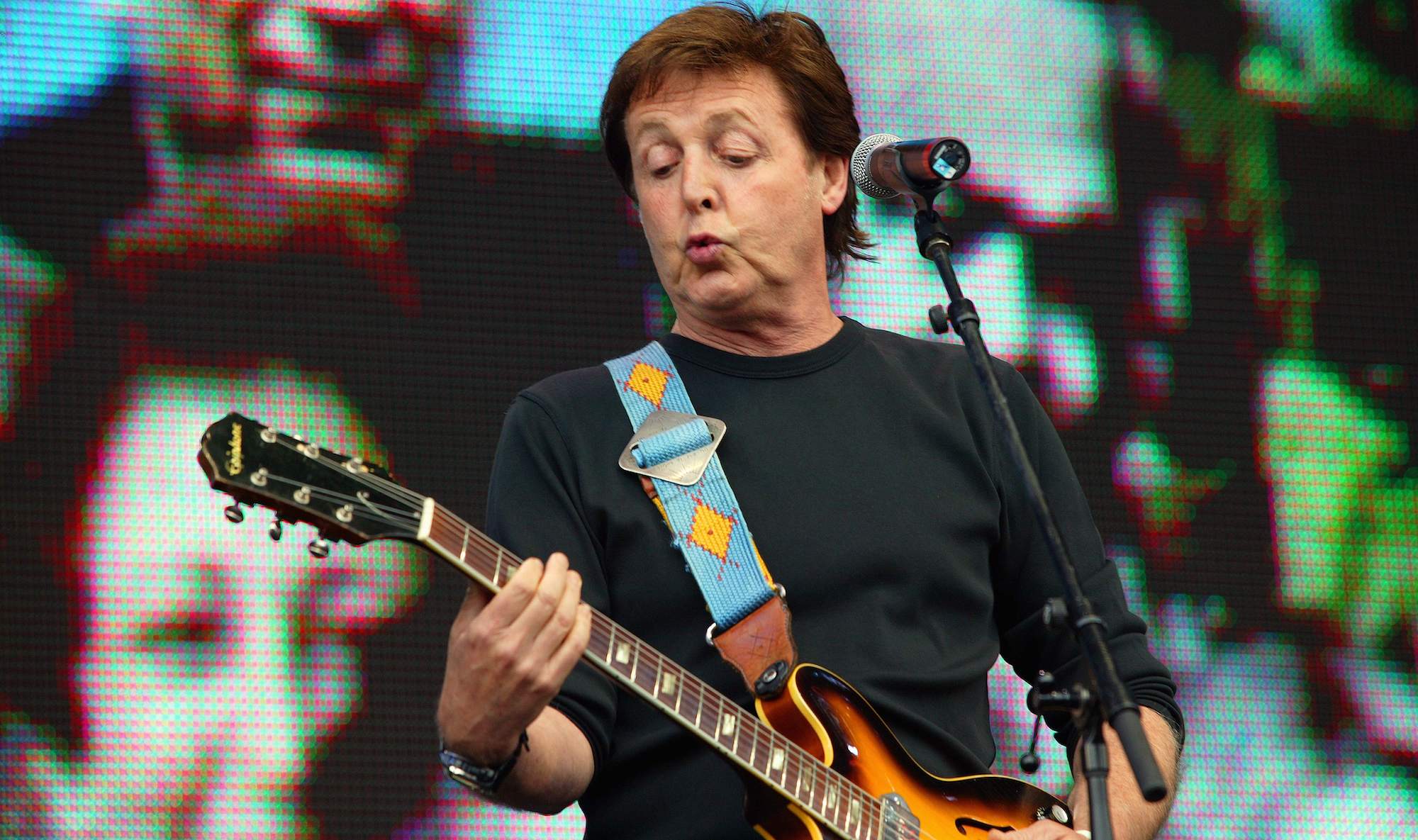

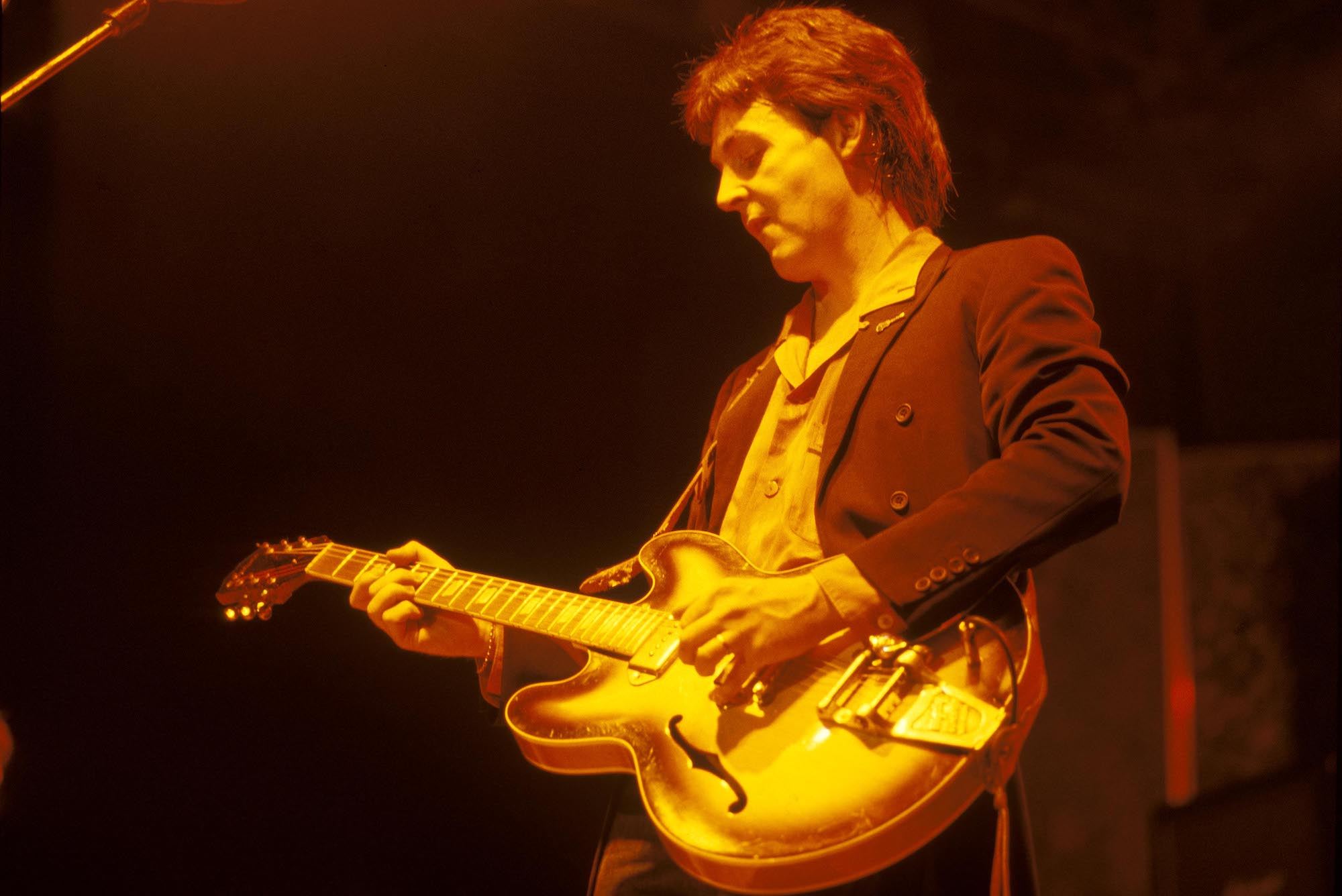

“Well, what happened was that we fell in love all over again with my Epiphone Casino, which I played on a lot of Beatles records – the 'Paperback Writer' riff, the solo on 'Taxman,' and so on. It also feeds back nicely. Nigel always kept going back to it, saying, 'That is my favorite guitar in the world!'

“I’d just get a little variation in the color by using either the treble or bass pickup, and then I’d stick it into my Vox AC30 – so it’s really the old Beatles sound. Thank goodness for my Epiphone Casino. Where would I be on this record without it?

“Occasionally, I’d pull out my goldtop Les Paul to do something a little bit more thrashing, and Nigel would say, 'Uh, it’s a bit heavy rock.' I’d say, 'Yeah, I think that will work.' Well, he’d have none of that. I mean, it got to be a bit of a joke, because every time I’d pull out the heavy rock, he’d say 'no.'

“It got to the point where I started to feel like some teenager trying to thrash in my bedroom, and daddy not letting me do it. But Nigel was right. The guitar sounds we recorded have a continuity that makes the album sound sort of holistic. You don’t feel like you’re going out of one room and into another. You just feel like you’re at Paul’s house.“

Given your ability to write in so many different genres, how do you discipline yourself to put a specific project in one stylistic place?

“I really do credit Nigel with doing that because, in a way, that’s a producer’s job. He has to take a look at what I’m doing and get enough variety, but, at the same time, to make a good album, everything must sound like it all came from the same hand so you feel like it’s not a patchwork quilt. There has to be something that pulls it all together, and I think that something is Nigel’s sound.“

Could you provide an example of how Nigel would encourage you to redirect a song that didn’t fit his view of the album’s vibe?

“'How Kind of You' was originally a jangly acoustic thing [sings the harmony], and Nigel said, 'Well, we can make it that way, and it will sound nice, but what if we tried a different production idea? What would you do if we didn’t use the acoustic?' We had a lot of organic, earthy instruments in the studio – including a really great pump organ. So I started pumping away on that, and it created an ocean of sound, rather than a deliberate rhythm.

“Then, we added some piano loops, and it produced this feeling of the ocean kind of rippling with the sun dappling on it first thing in the morning. When I sang the song over that, it was slightly unearthly. Now, when we eventually brought in the guitar, it really made a difference. Instead of it being there from the beginning until the end, it’s like 'Oh! Here’s the guitar.'“

On that note, the solo on “Promise to You Girl” really jumps out of the mix. I don’t think many people would be so brave as to mix something that rude and dry so far up in the mix.

“You know, if Nigel likes something, he mixes it right forward. That takes nerve, but that’s Nigel’s nerve. The guitar I used for that solo was the Casino. I kept trying to use other guitars, but Nigel would say, 'You know what we should try, don’t you?' And I’d say, 'Casino?' 'Yep!' [Laughs]

“The other funny thing about mixing things so dry happened on 'Jenny Wren.' I had heard this low, mournful flute during Ravi Shankar’s bit at the [2002] Concert for George [Harrison]. The instrument turned out to be a duduk, and we decided we had to have that sound on 'Jenny Wren.' So this Venezuelan duduk player, Pedro Eustache, comes to the studio, asks for some reverb in the headphones, and does a great take.

“During the playback, Nigel had the duduk absolutely flat and dry, and Pedro asked for some reverb. We said, 'No, Pedro – it’s beautiful as it is.' And that freaked him out! He said, 'No! You’ve got to have some reverb. That’s the loudest duduk I’ve ever heard!'“

On “Jenny Wren,” you employ a very individual fingerpicking style that pushes and pulls against your voice. What informed that approach?

“I should make up some great, glamorous story about that particular style, but it wouldn’t be true. The thing is, in our youth, the funky guys could fingerpick using all their fingers, and really do it right. John [Lennon] did that on 'Julia,' and he tried to show me how to fingerpick conventionally, but I could never quite do it.

“Still, I wanted to write something in that style, so I originally wrote 'Blackbird' using simultaneous melody and bass lines. But here’s the thing: I just kind of strum with my index finger whilst I’m sort of holding down the other two notes. That’s what gets that particular sound, and it’s just something that developed because I couldn’t do a proper fingerpicking thing.

“I wanted to revisit that style, so I used a similar approach on 'Jenny Wren.' Of course, on tour, I’d wear down the fingernail on my index finger until it drew blood. It was my wife, Heather, who suggested that I put on an acrylic nail. 'That’s what girls do,' she said. Well, that nail is a lifesaver.“

“The other thing about 'Jenny Wren' is that I’m playing my Epiphone Texan – the guitar I played 'Yesterday' on – which is permanently tuned down a tone. So I’m playing 'Jenny Wren' in C, which is more conducive for my guitar playing, but, with the tuning, the song is actually in Bb. It was the same with 'Yesterday.' I was playing in G, but the song was in F, which was a better key for my voice to sing that song in.“

The instrumental bonus track is a surprise. It sounds rough and ready – and it totally rocks – but it’s also very musical.

“Well, we were just looking at the puzzle of how to start an album, and we considered doing some sort of jam/noise thing for about a minute, and then go into the first song. That kind of thing takes the pressure off the first song.

“So Nigel asked me if I could just go in and make something up. I agreed to the challenge, and I got on the piano and tried to thrash something out that might be an opener. As I was going out to the studio, he said, 'Seeing as how you’re going to make up one thing, why don’t you make two pieces?' To which I thought, 'Well, maybe I’ll do three!'

“I very quickly got a little piano riff going for the first bit, then I got on the drums and bashed out a drum thing, and stuck a guitar on it. I was hopping from one instrument to the other without giving myself too much time to think. I would chug along on something, and Nigel was like a kid at Christmas. He’d say, 'Okay, can we have a high riff now?' I’d say, 'Sure! One high riff coming up.' And I’d just throw something on it.

“We had the feeling that if it didn’t work, it didn’t work. There was no pressure. It felt like the grownups had left the studio to us, and we were just like kids who got to do anything we wanted to. When we had done all the takes, we mixed them all up. The whole process took about three hours.

“However, when we tried the piece at the beginning of the album, we decided it didn’t really work. Instead, we made it a so-called 'hidden' track at the end of the album. Although, in this case, I think we should have called it a 'not-very-well hidden track, because it doesn’t wait more than 12 seconds before it comes in.“

The guitars are pretty ballsy on the hidden track. Did you finally get to pull out the Les Paul for that one?

“He still didn’t let me use it, man! Les is not going to be pleased! But I blame Nigel.“